Typical H2X installation, opposite the radio operator's position. Typical H2X installation, opposite the radio operator's position. | |

| Country of origin | USA |

|---|---|

| Type | air-to-ground radar system |

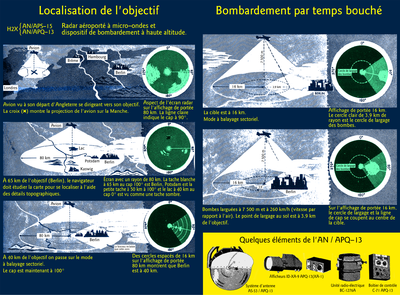

H2X, officially known as the AN/APS-15, was an American ground scanning radar system used for blind bombing during World War II. It was developed at the MIT Radiation Laboratory under direction of Dr. George E. Valley, jr. to replace the less accurate British H2S radar, the first ground mapping radar to be used in combat. H2X was also known as the "Mickey set" and "BTO" for "bombing through the overcast" radar.

H2X differed from the original H2S primarily in its 3-cm wavelength X band rather than H2S' 10-cm S band. This shorter wavelength gave H2X higher resolution than H2S, allowing it to provide usable images over large cities which appeared as a single blob on the H2S display. The Royal Air Force (RAF) initially considered using H2X as well, but would instead develop their own X band system, the H2S Mk. III. The RAF system entered service in late 1943, before the first use of H2X in early 1944.

The desire for even higher resolution, enough to image individual docks and bridges, led to a number of variations on the H2X system, as well as the more advanced AN/APQ-7 "Eagle" system. All of these were replaced in the post-war era with systems customized for the jet powered strategic bombers that entered service.

Usage

H2X was used by the USAAF during World War II as a navigation system for daylight overcast and nighttime operations. It was introduced as an improvement of the earlier H2S set, which had been supplied to the US to aid in the war effort. While the RAF Bomber Command utilized ground mapping radar as an aid to night area bombing, the primary use by the USAAF was as a fallback, to allow cities to be bombed even when hidden by cloud cover, an issue that had dogged their policy of precision daylight bombing since the start of the war, especially in cloud-prone Europe. With H2X, a city could be located and a general area targeted, night or day, cloud cover or no, with equal accuracy. H2X used a shorter 3 cm "centimetric" wavelength (10 GHz frequency) than the H2S, giving a higher angular resolution and thus a sharper picture, which allowed much finer details to be discerned, aiding in target identification. H2S subsequently also adopted 3 cm in the Mark III version entering operational service on 18 November 1943, for "Battle of Berlin").

H2X is not known to have ever been spotted by the German FuG 350 Naxos radar detector, due to that receiving device's specific purpose being to spot the original British H2S equipment's lower frequency, 3 GHz emissions.

Pathfinder missions

The first H2X-equipped B-17's arrived in England in early October 1943, and were first used in combat on 3 November 1943 when the USAAF VIII Bomber Command attacked the port of Wilhelmshaven. Those missions where bombing was done by H2X were called "Pathfinder missions" and the crews were called "Pathfinder crews", after the RAF practice of using highly trained Pathfinder crews to go in before the main bomber stream and identify and mark the target with flares.

Further information: Pathfinder (USAAF) and Pathfinder (RAF)American practice used their Pathfinder crews as lead bombers, with radar equipped aircraft being followed by formations of radar-less bombers, which would all drop their loads when the lead bomber did. The ventral hemispherical radome for the H2X's rotating dish antenna replaced the ball turret on B-17 Flying Fortress Pathfinders, with the electronics cabinets for the "Mickey set" being installed in the radio room just aft of the bomb bay. The system was used extensively by The 91st Bomb Group in 1945 with occasional excellent but generally inconsistent results.

The H2X on later B-24 Liberators also replaced the ball turret, being made retractable as the ball turret was for landing on the Liberator. The operators panel was installed on the flight deck behind the co-pilot (where the radio operator's normal position was). In combat areas the Mickey operator directed the pilot on headings to be taken, and on the bomb run directed the airplane in coordination with the bombardier. The first use of Mickey was against Ploiești on 5 April 1944.

Radar mapping of Germany

Due to the absence of radar maps, in late April 1944 six PR Mk.XVI de Havilland Mosquito aircraft in the 482nd Bomb Group were equipped with H2X equipment. The idea was to produce photographs of the radar screen during flights over Germany allowing easy interpretation of these radar images in later bombing runs. Three aircraft were subsequently lost in training, and the project was discontinued. A further twelve PR Mk.XVI Mosquitos of the 25th Bomb Group (Reconnaissance) of the Eighth Air Force were fitted with H2X and beginning in May 1944, flew radar mapping night missions until February 1945.

The sets tended to overload the Mosquito's electrical system and occasionally exploded. Mickey-equipped Mosquitos had the highest loss, abort, and mission failure rates of any version of the otherwise successful Mosquito reconnaissance aircraft, and were severely curtailed after 19 February 1945. Three were lost to enemy action and one was shot down by friendly fire from a Ninth Air Force P-47. In Europe several P-38 fighters were also converted to carrying H2X radar in the nose, along with an operator/navigator in a cramped compartment in the nose behind the radar dish, provided with small side windows and an access/exit hatch in the floor (much like the earlier P-38 "Droop Snoot" bomber-leader variants, but with a radome instead of a glazed nose). These missions were to obtain radar maps of German targets but plans to produce the variant in quantity never materialized.

B-29 equipment

In the Pacific theater, B-29’s were equipped with the improved H2X radar called the AN/APQ-13, a ground scanning radar developed by Bell, Western Electric, and MIT. The radome was carried on the aircraft belly between the bomb bays and was partially retractable. The radar operated at a frequency of 9,375 ± 45 megahertz and used a superheterodyne receiver. The radar was used for high altitude area bombing, search and navigation. Computation for bombing could be performed by an impact predictor. A range unit permitted a high degree of accuracy in locating beacons.

Post war usage

Post-war, the AN/APQ-13 became the first military radar converted to a domestic peacetime application as a storm warning radar. About thirty systems were converted and installed on military bases. It was replaced by the AN/CPS-9 system in 1949.

See also

Lists

- List of World War II electronic warfare equipment

- List of radars

- List of military electronics of the United States

References

- Steven K. Bailey (March 2019). Bold Venture: The American Bombing of Japanese-Occupied Hong Kong, 1942-1945. U of Nebraska Press. pp. 207–. ISBN 978-1-64012-162-1.

- L Brown (1 January 1999). Technical and Military Imperatives: A Radar History of World War 2. CRC Press. pp. 548–. ISBN 978-1-4200-5066-0.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/MIT_Radiation_Laboratory

- https://en.wikipedia.org/George_E._Valley_Jr.

- Jablonski, Edward (1971). Volume 2 (Wings of Fire), Book I (Kites over Berlin). Airpower. p. 49.

- Kevin A. Mahoney (20 August 2015). Bombing Europe: The Illustrated Exploits of the Fifteenth Air Force. Voyageur Press. pp. 239–. ISBN 978-0-7603-4815-4.

- Claus Reuter (June 2000). The Development of the Heavy Bomber 1918 - 1944, Aaf. German Canadian Museum of. pp. 74–. ISBN 978-1-894643-12-2.

- Watson, p. 191

- "322nd Dailies from 1945 - 91st Bomb Group (H)".

- Miller, Donald L. (2006). Masters of the Air: America's Bomber Boys Who Fought the Air War Against Nazi Germany. New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 118. ISBN 978-0-7432-3544-0.

Bibliography

- Freeman, Roger A. The Mighty Eighth War Diary (1990). ISBN 0-87938-495-6 page 240

- Watson, Raymond C. (2009). Radar Origins Worldwide: History of its Evolution in 13 Nations through World War II. n.p.: Trafford Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4269-2111-7.

- Fine, Norman (2019). Blind Bombing: How Microwave Radar brought the Allies to D-Day and Victory in World War II. Nebraska: Potomac Books/University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-1640-12279-6.

- Buderi, Robert (1996). The invention that changed the world (first ed.). New York, NY: Simon & Schuster. pp. 1–478. ISBN 0-684-81021-2.