| Han–Liu War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Map of Shandong, showing the railway between Jinan ("Tsi-nan-fu") and Qingdao ("Tsingtao") in the west and the mountainous Shandong Peninsula in the east. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Han Fuju | Liu Zhennian | ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

NRA units loyal to Han, Republic of China Navy | NRA units loyal to Liu | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 80,000 | 20,000–30,000 | ||||||

The Han–Liu War (Chinese: 韓劉之戰) was a major military conflict in late 1932 between the private armies of Han Fuju and Liu Zhennian over Shandong. Even though Han as well as Liu were officially subordinates to the Chinese Nationalist government in Nanjing, both were effectively warlords with their own autonomous territories. Han Fuju controlled most of Shandong and had long desired to also capture the eastern part of the province, which was held by Liu. The tensions between the two eventually escalated, leading to a war that saw Han emerge victorious. He went on to rule Shandong unopposed for the next six years, while Liu was exiled to southern China.

Background

Han Fuju, official governor of Shandong

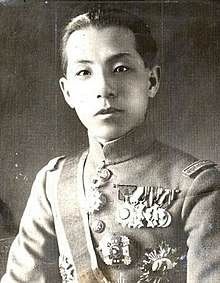

Han Fuju, official governor of Shandong Liu Zhennian, ruler of eastern Shandong

Liu Zhennian, ruler of eastern Shandong

Despite the Chinese Nationalists' victory during the Northern Expedition in 1928 and the reunification of China under the Nanjing government, warlordism throughout the nation did not end. Many warlords had opportunistically sided with the Nationalists, and had been allowed to keep their private armies as well as territories as long as they submitted to the new central government. Among these opportunistic military strongmen were Han Fuju and Liu Zhennian. Originally a follower of Feng Yuxiang, Han defected to the Nationalists during the Central Plains War and was awarded the governorship of Shandong in 1930. He subsequently consolidated most of the province under his rule, with the exception of the Shandong Peninsula in its east. This area was held by Liu, who had already sided with the Nationalists in 1928 and been allowed to run eastern Shandong as his personal fiefdom. Although challenged by a rebellion instigated by Zhang Zongchang and a peasant insurgency, Liu had managed to remain in power since then.

As result, the province of Shandong was effectively divided between these two warlords. While Liu was mostly content with this situation, and simply desired to maintain his "comfortable existence in his eastern stronghold", Han saw things differently. He wanted to bring Shandong "stability and prosperity, and protection from internal turbulence and from unnecessary warfare". Liu, whose ruthlessness caused banditry and peasant insurgencies, was thus seen as disruptive factor that Han wanted to remove. Another major point of contention between the two were the monthly allowances they received from the government. Allowances were given to all military governors so that they could maintain their armies, and thus crucial to any power struggle; thanks to his governorship, Han had the advantage in this regard. Han and Liu consequently grew into bitter rivals, though they initially remained at peace. The tensions between them finally escalated in 1932, when Han Fuju decided to launch a campaign to eliminate his rival and consolidate all of Shandong under his rule once and for all.

Opposing forces

Although both were part of the National Revolutionary Army, the private armies of Han and Liu greatly differed in their military prowess: As official governor Han Fuju had 80,000 men under his command, slightly more light artillery and machine guns, and significantly more medium and heavy artillery than Liu. His troops had high morale and were extremely loyal, since Han treated them well and forged an identity of "brother soldiers" among them. Furthermore, he even possessed his own air force, consisting of bomber and reconnaissance aircraft in form of six modern trainers and possibly a few old Breguet 14 biplanes.

On the other side, Liu Zhennian's army consisted of 20,000–30,000 men with much fewer artillery pieces than his rival. Despite their generally disadvantageous position, however, Liu's troops were relatively well trained and also quite loyal to their commander. Many even resolved to fight to the death before the outbreak of hostilities and bought coffins in anticipation of their possible demise. Another minor advantage that Liu possessed was that his rival lacked sufficient motor transport to move all his forces, instead relying on the few available regional trains as well as confiscated civilian carts. This inevitably slowed down Han's troops and made control of roads and the rail network crucial; if Liu could manage to hold these, he could possibly delay or stop an offensive launched by Han.

War

Map of the eastern Shandong Peninsula from 1917, showing its road network and rivers. Liu Zhennian's de facto capital Zhifu ("Chefoo") was only accessible by few land routes.

Map of the eastern Shandong Peninsula from 1917, showing its road network and rivers. Liu Zhennian's de facto capital Zhifu ("Chefoo") was only accessible by few land routes.

Shortly before the outbreak of hostilities, Han reinforced his garrisons at important roads leading to Zhifu, Liu's de facto capital, with troops drawn from western Shandong. When he ordered his soldiers to secure the important Qingdao–Jinan railway, however, they encountered resistance by Liu's troops. A first skirmish occurred on 17 September, which marked the war's beginning. Han then launched an all-out offensive with all of his available forces, resulting in several small but fierce actions along the railway. Despite his technical and numerical superiority, Han failed to dislodge Liu's men and the fighting turned into a "bloody stalemate". Meanwhile, the central government called for a ceasefire and urged both warlords to settle their disputes at a peace conference in Nanjing. Though these calls for peace were ignored, the central authorities initially chose not to directly intervene in the conflict, as Chiang Kai-shek regarded it as a "local matter". Neither Han nor Liu were really loyal to the Nationalist government, which in turn never really trusted the two and was not eager to provide any aid to either one, though it still slightly preferred Han due to his official governorship.

As he was not able to secure the railways, Han instead shifted his attention to the roads to Zhifu. Though these roads were of poor quality and his army lacked enough motor transport, reducing the speed of Han's army, its mass advance along the roads quickly proved to be unstoppable. Every time Liu's men attempted to dig in and stop the offensive, Han used his superior artillery to simply shell them until they could be overwhelmed with infantry. His small airforce also helped by launching regular air raids. Liu tried to hinder his rival's advance by blowing up one of the main bridges to Zhifu, but this too had little effect. It became clear that Liu had no chance to win the war. One of his regiments chose to defect because of this, but most of Liu's soldiers nevertheless remained loyal.

As Han's army advanced deeper into Liu's territory, the central government finally decided to intervene in the conflict. This was due to the Empire of Japan having extensive business interests in eastern Shandong, which when threatened by the Han–Liu War could result in a Japanese military intervention – something that the Nationalists wanted to prevent at all costs. Chiang Kai-shek consequently requested Zhang Xueliang to send one of his naval units to capture Zhifu, which was the only local harbor also usable in winter and thus strategically very important. Zhang's navy arrived at and occupied Zhifu on 24 September without any opposition. Liu's garrison had abandoned the town on the night before, probably in anticipation of the naval landing.

Although the capture of Zhifu at the hands of the government meant that Liu was now considered a "rebel" and his position had become untenable, he still refused an offer by Han to a ceasefire on 26 September. Instead, Liu retreated with his remaining forces into Shandong's hinterland in order to continue his resistance. The following campaign in the countryside was marked by the great suffering of the local civilians, who were targeted by Liu's troops out of the frustration about their defeats while Han's army attacked them as perceived supporters of Liu. Thousands fled to Zhifu, where the government set up refugee camps. In contrast to the violence meted out against the civilian population, the two armies only rarely clashed in combat during this phase of the war. Instead, Han and Liu waged a propaganda war, accusing each other of being Communist sympathisers, the greatest insult for a Chinese officer at the time. Han also publicly declared that he regretted the widespread destruction caused by his war against Liu, but also stated that his "conscience will not feel at ease" as long as his rival continued to be active in Shandong.

The conflict continued until early November, when Liu finally agreed to a peace agreement. Liu was allowed to keep his remaining army, but he and his men were exiled to southern China, from which they were not allowed to return. Han thus became the unopposed ruler of the whole Shandong province.

Aftermath

Though his governing style was autocratic, Han proved to be a capable civilian administrator whose relatively low taxes and operations against banditry made him popular among the people. Furthermore, his rule brought an unprecedented time of peace and stability to Shandong, which had suffered under constant upheavals, wars and rebellions since before the Warlord era's beginning. The Second Sino-Japanese War brought his downfall, however, when he abandoned Jinan to the Imperial Japanese Army against Chiang Kai-shek's orders. As an example to those who refused to stand and fight, Han was subsequently arrested and executed by the Nationalist government in 1938. His execution had a devastating effect on the morale of his army and Shandong's civilian population, who lost their confidence in the Chinese government. Most of his soldiers even turned against the Nationalists, first joining the pro-Japanese Collaborationist Chinese Army and then the Communist People's Liberation Army.

References

- ^ Jowett (2017), p. 206.

- Jowett (2017), pp. 1–6.

- Shen (2001), pp. 77, 78.

- Jowett (2017), pp. 32, 33, 43, 45, 206.

- ^ Lary (2006), p. 70.

- Jowett (2017), pp. 45, 196, 197.

- ^ Bianco (2015), pp. 5, 6.

- ^ Graefe (2008), p. 137.

- Jowett (2017), pp. 196–200.

- ^ Jowett (2017), pp. 206, 207.

- ^ Lary (2006), p. 71.

- ^ Jowett (2017), p. 207.

- ^ Jowett (2017), pp. 206–208.

- Jowett (2017), pp. 45, 196, 198.

- ^ Shen (2001), pp. 78, 79.

- Jowett (2017), pp. 207, 208.

- ^ Jowett (2017), p. 208.

- Shen (2001), p. 79.

Bibliography

- Bianco, Lucien (2015). Peasants without the Party: Grassroots Movements in Twentieth Century China. Abingdon-on-Thames, New York City: Routledge. ISBN 978-1563248405.

- Graefe, Nils (2008). Liu Guitang (1892-1943): Einer der größten Banditen der chinesischen Republikzeit [Liu Guitang (1892-1943): One of the greatest bandits of the Chinese Republican Era] (in German). Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 978-3447058247.

- Jowett, Philip S. (2017). The Bitter Peace. Conflict in China 1928–37. Stroud: Amberley Publishing. ISBN 978-1445651927.

- Lary, Diana (2006). "Treachery, Disgrace and Death: Han Fuju and China's Resistance to Japan". War in History. 13 (1): 65–90. doi:10.1191/0968344506wh332oa. S2CID 159592014.

- Shen, Zhijia (2001). "Nationalism in the Context of Survival: The Sino-Japanese War Fought in a Local Arena, Zouping, 1937-1945". In C. X. George Wei; Xiaoyuan Liu (eds.). Chinese Nationalism in Perspective: Historical and Recent Cases. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 75–100.