| Mathematical analysis → Complex analysis |

| Complex analysis |

|---|

|

| Complex numbers |

| Complex functions |

| Basic theory |

| Geometric function theory |

| People |

In mathematics, mathematical physics and the theory of stochastic processes, a harmonic function is a twice continuously differentiable function where U is an open subset of that satisfies Laplace's equation, that is, everywhere on U. This is usually written as or

Etymology of the term "harmonic"

The descriptor "harmonic" in the name harmonic function originates from a point on a taut string which is undergoing harmonic motion. The solution to the differential equation for this type of motion can be written in terms of sines and cosines, functions which are thus referred to as harmonics. Fourier analysis involves expanding functions on the unit circle in terms of a series of these harmonics. Considering higher dimensional analogues of the harmonics on the unit n-sphere, one arrives at the spherical harmonics. These functions satisfy Laplace's equation and over time "harmonic" was used to refer to all functions satisfying Laplace's equation.

Examples

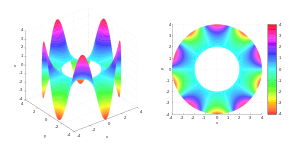

Examples of harmonic functions of two variables are:

- The real or imaginary part of any holomorphic function.

- The function this is a special case of the example above, as and is a holomorphic function. The second derivative with respect to x is while the second derivative with respect to y is

- The function defined on This can describe the electric potential due to a line charge or the gravity potential due to a long cylindrical mass.

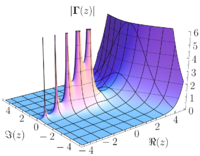

Examples of harmonic functions of three variables are given in the table below with

Function Singularity Unit point charge at origin x-directed dipole at origin Line of unit charge density on entire z-axis Line of unit charge density on negative z-axis Line of x-directed dipoles on entire z axis Line of x-directed dipoles on negative z axis

Harmonic functions that arise in physics are determined by their singularities and boundary conditions (such as Dirichlet boundary conditions or Neumann boundary conditions). On regions without boundaries, adding the real or imaginary part of any entire function will produce a harmonic function with the same singularity, so in this case the harmonic function is not determined by its singularities; however, we can make the solution unique in physical situations by requiring that the solution approaches 0 as r approaches infinity. In this case, uniqueness follows by Liouville's theorem.

The singular points of the harmonic functions above are expressed as "charges" and "charge densities" using the terminology of electrostatics, and so the corresponding harmonic function will be proportional to the electrostatic potential due to these charge distributions. Each function above will yield another harmonic function when multiplied by a constant, rotated, and/or has a constant added. The inversion of each function will yield another harmonic function which has singularities which are the images of the original singularities in a spherical "mirror". Also, the sum of any two harmonic functions will yield another harmonic function.

Finally, examples of harmonic functions of n variables are:

- The constant, linear and affine functions on all of (for example, the electric potential between the plates of a capacitor, and the gravity potential of a slab)

- The function on for n > 2.

Properties

The set of harmonic functions on a given open set U can be seen as the kernel of the Laplace operator Δ and is therefore a vector space over linear combinations of harmonic functions are again harmonic.

If f is a harmonic function on U, then all partial derivatives of f are also harmonic functions on U. The Laplace operator Δ and the partial derivative operator will commute on this class of functions.

In several ways, the harmonic functions are real analogues to holomorphic functions. All harmonic functions are analytic, that is, they can be locally expressed as power series. This is a general fact about elliptic operators, of which the Laplacian is a major example.

The uniform limit of a convergent sequence of harmonic functions is still harmonic. This is true because every continuous function satisfying the mean value property is harmonic. Consider the sequence on defined by this sequence is harmonic and converges uniformly to the zero function; however note that the partial derivatives are not uniformly convergent to the zero function (the derivative of the zero function). This example shows the importance of relying on the mean value property and continuity to argue that the limit is harmonic.

Connections with complex function theory

The real and imaginary part of any holomorphic function yield harmonic functions on (these are said to be a pair of harmonic conjugate functions). Conversely, any harmonic function u on an open subset Ω of is locally the real part of a holomorphic function. This is immediately seen observing that, writing the complex function is holomorphic in Ω because it satisfies the Cauchy–Riemann equations. Therefore, g locally has a primitive f, and u is the real part of f up to a constant, as ux is the real part of

Although the above correspondence with holomorphic functions only holds for functions of two real variables, harmonic functions in n variables still enjoy a number of properties typical of holomorphic functions. They are (real) analytic; they have a maximum principle and a mean-value principle; a theorem of removal of singularities as well as a Liouville theorem holds for them in analogy to the corresponding theorems in complex functions theory.

Properties of harmonic functions

Some important properties of harmonic functions can be deduced from Laplace's equation.

Regularity theorem for harmonic functions

Harmonic functions are infinitely differentiable in open sets. In fact, harmonic functions are real analytic.

Maximum principle

Harmonic functions satisfy the following maximum principle: if K is a nonempty compact subset of U, then f restricted to K attains its maximum and minimum on the boundary of K. If U is connected, this means that f cannot have local maxima or minima, other than the exceptional case where f is constant. Similar properties can be shown for subharmonic functions.

The mean value property

If B(x, r) is a ball with center x and radius r which is completely contained in the open set then the value u(x) of a harmonic function at the center of the ball is given by the average value of u on the surface of the ball; this average value is also equal to the average value of u in the interior of the ball. In other words, where ωn is the volume of the unit ball in n dimensions and σ is the (n − 1)-dimensional surface measure.

Conversely, all locally integrable functions satisfying the (volume) mean-value property are both infinitely differentiable and harmonic.

In terms of convolutions, if denotes the characteristic function of the ball with radius r about the origin, normalized so that the function u is harmonic on Ω if and only if as soon as

Sketch of the proof. The proof of the mean-value property of the harmonic functions and its converse follows immediately observing that the non-homogeneous equation, for any 0 < s < r admits an easy explicit solution wr,s of class C with compact support in B(0, r). Thus, if u is harmonic in Ω holds in the set Ωr of all points x in Ω with

Since u is continuous in Ω, converges to u as s → 0 showing the mean value property for u in Ω. Conversely, if u is any function satisfying the mean-value property in Ω, that is, holds in Ωr for all 0 < s < r then, iterating m times the convolution with χr one has: so that u is because the m-fold iterated convolution of χr is of class with support B(0, mr). Since r and m are arbitrary, u is too. Moreover, for all 0 < s < r so that Δu = 0 in Ω by the fundamental theorem of the calculus of variations, proving the equivalence between harmonicity and mean-value property.

This statement of the mean value property can be generalized as follows: If h is any spherically symmetric function supported in B(x, r) such that then In other words, we can take the weighted average of u about a point and recover u(x). In particular, by taking h to be a C function, we can recover the value of u at any point even if we only know how u acts as a distribution. See Weyl's lemma.

Harnack's inequality

Let be a connected set in a bounded domain Ω. Then for every non-negative harmonic function u, Harnack's inequality holds for some constant C that depends only on V and Ω.

Removal of singularities

The following principle of removal of singularities holds for harmonic functions. If f is a harmonic function defined on a dotted open subset of , which is less singular at x0 than the fundamental solution (for n > 2), that is then f extends to a harmonic function on Ω (compare Riemann's theorem for functions of a complex variable).

Liouville's theorem

Theorem: If f is a harmonic function defined on all of which is bounded above or bounded below, then f is constant.

(Compare Liouville's theorem for functions of a complex variable).

Edward Nelson gave a particularly short proof of this theorem for the case of bounded functions, using the mean value property mentioned above:

Given two points, choose two balls with the given points as centers and of equal radius. If the radius is large enough, the two balls will coincide except for an arbitrarily small proportion of their volume. Since f is bounded, the averages of it over the two balls are arbitrarily close, and so f assumes the same value at any two points.

The proof can be adapted to the case where the harmonic function f is merely bounded above or below. By adding a constant and possibly multiplying by –1, we may assume that f is non-negative. Then for any two points x and y, and any positive number R, we let We then consider the balls BR(x) and Br(y) where by the triangle inequality, the first ball is contained in the second.

By the averaging property and the monotonicity of the integral, we have (Note that since vol BR(x) is independent of x, we denote it merely as vol BR.) In the last expression, we may multiply and divide by vol Br and use the averaging property again, to obtain But as the quantity tends to 1. Thus, The same argument with the roles of x and y reversed shows that , so that

Another proof uses the fact that given a Brownian motion Bt in such that we have for all t ≥ 0. In words, it says that a harmonic function defines a martingale for the Brownian motion. Then a probabilistic coupling argument finishes the proof.

Generalizations

Weakly harmonic function

A function (or, more generally, a distribution) is weakly harmonic if it satisfies Laplace's equation in a weak sense (or, equivalently, in the sense of distributions). A weakly harmonic function coincides almost everywhere with a strongly harmonic function, and is in particular smooth. A weakly harmonic distribution is precisely the distribution associated to a strongly harmonic function, and so also is smooth. This is Weyl's lemma.

There are other weak formulations of Laplace's equation that are often useful. One of which is Dirichlet's principle, representing harmonic functions in the Sobolev space H(Ω) as the minimizers of the Dirichlet energy integral with respect to local variations, that is, all functions such that holds for all or equivalently, for all

Harmonic functions on manifolds

Harmonic functions can be defined on an arbitrary Riemannian manifold, using the Laplace–Beltrami operator Δ. In this context, a function is called harmonic if Many of the properties of harmonic functions on domains in Euclidean space carry over to this more general setting, including the mean value theorem (over geodesic balls), the maximum principle, and the Harnack inequality. With the exception of the mean value theorem, these are easy consequences of the corresponding results for general linear elliptic partial differential equations of the second order.

Subharmonic functions

A C function that satisfies Δf ≥ 0 is called subharmonic. This condition guarantees that the maximum principle will hold, although other properties of harmonic functions may fail. More generally, a function is subharmonic if and only if, in the interior of any ball in its domain, its graph lies below that of the harmonic function interpolating its boundary values on the ball.

Harmonic forms

One generalization of the study of harmonic functions is the study of harmonic forms on Riemannian manifolds, and it is related to the study of cohomology. Also, it is possible to define harmonic vector-valued functions, or harmonic maps of two Riemannian manifolds, which are critical points of a generalized Dirichlet energy functional (this includes harmonic functions as a special case, a result known as Dirichlet principle). This kind of harmonic map appears in the theory of minimal surfaces. For example, a curve, that is, a map from an interval in to a Riemannian manifold, is a harmonic map if and only if it is a geodesic.

Harmonic maps between manifolds

Main article: Harmonic mapIf M and N are two Riemannian manifolds, then a harmonic map is defined to be a critical point of the Dirichlet energy in which is the differential of u, and the norm is that induced by the metric on M and that on N on the tensor product bundle

Important special cases of harmonic maps between manifolds include minimal surfaces, which are precisely the harmonic immersions of a surface into three-dimensional Euclidean space. More generally, minimal submanifolds are harmonic immersions of one manifold in another. Harmonic coordinates are a harmonic diffeomorphism from a manifold to an open subset of a Euclidean space of the same dimension.

See also

- Balayage

- Biharmonic map

- Dirichlet problem

- Harmonic morphism

- Harmonic polynomial

- Heat equation

- Laplace equation for irrotational flow

- Poisson's equation

- Quadrature domains

Notes

- Axler, Sheldon; Bourdon, Paul; Ramey, Wade (2001). Harmonic Function Theory. New York: Springer. p. 25. ISBN 0-387-95218-7.

- Nelson, Edward (1961). "A proof of Liouville's theorem". Proceedings of the American Mathematical Society. 12 (6): 995. doi:10.1090/S0002-9939-1961-0259149-4.

- "Probabilistic Coupling". Blame It On The Analyst. 2012-01-24. Archived from the original on 8 May 2021. Retrieved 2022-05-26.

References

- Evans, Lawrence C. (1998), Partial Differential Equations, American Mathematical Society.

- Gilbarg, David; Trudinger, Neil (12 January 2001), Elliptic Partial Differential Equations of Second Order, Springer, ISBN 3-540-41160-7.

- Han, Q.; Lin, F. (2000), Elliptic Partial Differential Equations, American Mathematical Society.

- Jost, Jürgen (2005), Riemannian Geometry and Geometric Analysis (4th ed.), Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-3-540-25907-7.

- Axler, Sheldon; Bourdon, Paul; Ramey, Wade (2001), Harmonic Function Theory, vol. 137 (Second ed.), New York: Springer-Verlag, doi:10.1007/978-1-4757-8137-3, ISBN 0-387-95218-7.

External links

- "Harmonic function", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, EMS Press, 2001

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Harmonic Function". MathWorld.

- Harmonic Function Theory by S.Axler, Paul Bourdon, and Wade Ramey

where U is an

where U is an  that satisfies

that satisfies  everywhere on U. This is usually written as

everywhere on U. This is usually written as

or

or

this is a special case of the example above, as

this is a special case of the example above, as  and

and  is a

is a  while the second derivative with respect to y is

while the second derivative with respect to y is

defined on

defined on  This can describe the electric potential due to a line charge or the gravity potential due to a long cylindrical mass.

This can describe the electric potential due to a line charge or the gravity potential due to a long cylindrical mass.

(for example, the

(for example, the  on

on  for n > 2.

for n > 2. linear combinations of harmonic functions are again harmonic.

linear combinations of harmonic functions are again harmonic.

defined by

defined by  this sequence is harmonic and converges uniformly to the zero function; however note that the partial derivatives are not uniformly convergent to the zero function (the derivative of the zero function). This example shows the importance of relying on the mean value property and continuity to argue that the limit is harmonic.

this sequence is harmonic and converges uniformly to the zero function; however note that the partial derivatives are not uniformly convergent to the zero function (the derivative of the zero function). This example shows the importance of relying on the mean value property and continuity to argue that the limit is harmonic.

(these are said to be a pair of

(these are said to be a pair of  the complex function

the complex function  is holomorphic in Ω because it satisfies the

is holomorphic in Ω because it satisfies the

then the value u(x) of a harmonic function

then the value u(x) of a harmonic function  at the center of the ball is given by the average value of u on the surface of the ball; this average value is also equal to the average value of u in the interior of the ball. In other words,

at the center of the ball is given by the average value of u on the surface of the ball; this average value is also equal to the average value of u in the interior of the ball. In other words,

where ωn is the volume of the unit ball in n dimensions and σ is the (n − 1)-dimensional surface measure.

where ωn is the volume of the unit ball in n dimensions and σ is the (n − 1)-dimensional surface measure.

denotes the

denotes the  the function u is harmonic on Ω if and only if

the function u is harmonic on Ω if and only if

as soon as

as soon as

admits an easy explicit solution wr,s of class C with compact support in B(0, r). Thus, if u is harmonic in Ω

admits an easy explicit solution wr,s of class C with compact support in B(0, r). Thus, if u is harmonic in Ω

holds in the set Ωr of all points x in Ω with

holds in the set Ωr of all points x in Ω with

converges to u as s → 0 showing the mean value property for u in Ω. Conversely, if u is any

converges to u as s → 0 showing the mean value property for u in Ω. Conversely, if u is any  function satisfying the mean-value property in Ω, that is,

function satisfying the mean-value property in Ω, that is,

holds in Ωr for all 0 < s < r then, iterating m times the convolution with χr one has:

holds in Ωr for all 0 < s < r then, iterating m times the convolution with χr one has:

so that u is

so that u is  because the m-fold iterated convolution of χr is of class

because the m-fold iterated convolution of χr is of class  with support B(0, mr). Since r and m are arbitrary, u is

with support B(0, mr). Since r and m are arbitrary, u is  too. Moreover,

too. Moreover,

for all 0 < s < r so that Δu = 0 in Ω by the fundamental theorem of the calculus of variations, proving the equivalence between harmonicity and mean-value property.

for all 0 < s < r so that Δu = 0 in Ω by the fundamental theorem of the calculus of variations, proving the equivalence between harmonicity and mean-value property.

then

then  In other words, we can take the weighted average of u about a point and recover u(x). In particular, by taking h to be a C function, we can recover the value of u at any point even if we only know how u acts as a

In other words, we can take the weighted average of u about a point and recover u(x). In particular, by taking h to be a C function, we can recover the value of u at any point even if we only know how u acts as a  be a connected set in a bounded domain Ω.

Then for every non-negative harmonic function u,

be a connected set in a bounded domain Ω.

Then for every non-negative harmonic function u,

holds for some constant C that depends only on V and Ω.

holds for some constant C that depends only on V and Ω.

of

of  then f extends to a harmonic function on Ω (compare

then f extends to a harmonic function on Ω (compare  We then consider the balls BR(x) and Br(y) where by the triangle inequality, the first ball is contained in the second.

We then consider the balls BR(x) and Br(y) where by the triangle inequality, the first ball is contained in the second.

(Note that since vol BR(x) is independent of x, we denote it merely as vol BR.) In the last expression, we may multiply and divide by vol Br and use the averaging property again, to obtain

(Note that since vol BR(x) is independent of x, we denote it merely as vol BR.) In the last expression, we may multiply and divide by vol Br and use the averaging property again, to obtain

But as

But as  the quantity

the quantity

tends to 1. Thus,

tends to 1. Thus,  The same argument with the roles of x and y reversed shows that

The same argument with the roles of x and y reversed shows that  , so that

, so that

we have

we have  for all t ≥ 0. In words, it says that a harmonic function defines a

for all t ≥ 0. In words, it says that a harmonic function defines a  in a

in a  with respect to local variations, that is, all functions

with respect to local variations, that is, all functions  such that

such that  holds for all

holds for all  or equivalently, for all

or equivalently, for all

Many of the properties of harmonic functions on domains in Euclidean space carry over to this more general setting, including the mean value theorem (over

Many of the properties of harmonic functions on domains in Euclidean space carry over to this more general setting, including the mean value theorem (over  to a Riemannian manifold, is a harmonic map if and only if it is a

to a Riemannian manifold, is a harmonic map if and only if it is a  is defined to be a critical point of the Dirichlet energy

is defined to be a critical point of the Dirichlet energy

in which

in which  is the differential of u, and the norm is that induced by the metric on M and that on N on the tensor product bundle

is the differential of u, and the norm is that induced by the metric on M and that on N on the tensor product bundle