| Part of a series on |

| Hermeticism |

|---|

Hermes Trismegistus Hermes Trismegistus |

| Hermetic writings |

Historical figures

|

| Modern offshoots |

This is a comparative religion article which outlines the similarities and interactions between Hermeticism (or Hermetism) and other religions or philosophies. It highlights its similarities and differences with Gnosticism, examines its connections in Islam and Judaism, delves into its influence on Christianity, and even explores its potential impact on Mormonism. In essence, it unveils how Hermeticism has engaged with, influenced, and been influenced by a diverse array of spiritual and philosophical traditions throughout history.

Gnosticism

Hermetism is related to a wider intellectual current known as Gnosticism. Both flourished in the same period in Roman Egypt, in the same spiritual climate, sharing the goal of allowing the soul to escape from the material realm, and emphasizing a personal knowledge of God. Both groups held that the fundamental relationship between God and man could be found through gnosis (knowledge through experience; understanding), with the goal to "see" God, and in some instances to become one with God.

However, there are also some significant differences between Hermetism and Gnosticism with regard to philosophical theology, cosmology, and anthropology. Though both agreed about God's transcendence over the Universe, Hermetists sometimes believed that God could still be comprehended through philosophical reasoning, in agreement with philosophers and Christian theologians, whereas many Gnostics felt that God was completely unknowable. While the Gnostics often indulged in and expanded upon mythological references, Hermetic texts are relatively devoid of mythology (the exceptions being Book I, Poimandres, Book III, the Sacred Sermon, and the Book IV, the Sacred Cup, or Monad). Hermetism is generally optimistic about God, while many forms of Christian Gnosticism are pessimistic about the creator—several Christian Gnostic sects saw the cosmos as the product of an evil creator, and thus as being evil itself, while Hermetists saw the cosmos as a beautiful creation in the image of God. Both held that mankind was originally divine and has become entrapped in the material world, a slave to passion and distracted from divine nature. However, the Gnostics as a result often adopted a pessimistic view of mankind, while the Hermetic belief system generally retained a positive attitude towards humanity. Hermetists believed that the human body was not evil in and of itself, but that materialistic impulses such as sexual desire were the cause of evil in the world.

Islam

According to ninth- and tenth-century Arabic authors, the pagan community from the Upper-Mesopotamian city of Harran (who self-identified as the Sabians mentioned in the Qur'an) counted Hermes Trismegistus as one of their major prophets. In the same period some Muslims started to identify the Qur'anic prophet Idrīs (the Islamic equivalent to the Biblical Enoch) with Hermes. In this context, Hermes came to be seen as a 'prophet of science'.

Judaism

The relationship between ancient Judaism and Hermetism has been one of mutual influence and a subject of controversy within the Jewish religion.

Middle Ages

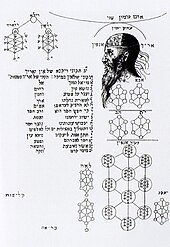

This identification paved the way for the exchange and melding of ideas between Judaism and Hermetism during the Middle Ages. The most prominent interrelation between the two systems is in the development of Kabbalah, which developed into three separate brands: a Jewish stream, a Christian stream (Cabala in Christianity), and a Hermetic stream (Qabalah in Hermeticism). Medieval Hermetism, aside from alchemy, is often seen as analogous to (and was heavily influenced by) these Kabbalistic ideas.

Hermetism and Kabbalah arose together in the 12th and 13th centuries. The Practical Kabbalah also relied upon magic and astrology but focused more on the Hebrew language in its incantations than the general language of Hermetism in general.

Secondly, Jewish scholars of the Middle Ages attempted to make use of treatises on astrology, medicine and theurgy as a justification for practicing natural magic forbidden by a number of commandments in the Torah and reinforced by prophetic books codified by rabbinic authorities. They noted the wonders performed by celebrated biblical figures such as the patriarchs and King Solomon and which were seen as a God-given and condoned use of natural magic. They attributed these arts to divine knowledge imparted by Jewish heroes to gentiles such as the Indians, Babylonians, Egyptians, and Greeks, and felt that by approaching magic from a religious standpoint would legitimize their use of the sciences. In particular, they believed the Hermetic teachings to have its origins in ancient Jewish sources.

These Jewish scholars, particularly the ones who distrusted Aristotelian rationality, looked to Hermetism as a backing to discuss theological interpretation of the Torah and the Ten Commandments. Fabrizo Lelli writes: "As for Christians and Muslims, so likewise for Jews, Hermetism was an alternative to Aristotelianism--the likeliest prospect, in fact, for integrating an alien system into their religion. This was because the response of the Hermetica to intellectual problems was generally theosophical."

In the use of these Hermetic treatises, these Jewish scholars, though at times inadvertently, introduced Hermetic ideas into Jewish thought. Shabbetay Donnolo's 10th century commentary on the Sefer Yezirah shows Hermetic influence, as well as the 13th century texts later compiled into the Sefer ha-Zohar, and in the contemporary Kabbalistic works of Abraham Abulafia as well as of other Jewish thinkers influenced by Kabbalah such as Isaac Abravanel who used Hermetic Qabalah to affirm the superiority of Judaism. Lelli suggests that it was natural for these Jewish Kabbalists to elevate Hermetic teachings to a major role in Jewish thought in a time when they began to produce their own "antirationalist--exegesis of scripture." This was despite the fact that many Hermetic works were ascribed to Aristotle in the time through pseudepigrapha; these scholars saw that as a justification to give the same elevated authority to the medical, astronomical, and magical Hermetic texts.

However, most Medieval Jewish scholars aware of the Hermetic tradition did not mention Hermetism explicitly, but rather referred to them through Hermetic ideas that were borrowed from Islam or brought Hermeticism up only to reject it. While scholars such as Moses ibn Ezra, Bahya ibn Paquda, Judah ha-Levi, and Abraham ibn Ezra specifically brought up Hermeticism to integrate into their philosophies, others such as Moses ben Maimon (Maimonides) specifically rejected anything Hermetic as being responsible for counterparadigmic views of God. Maimonides warned his readers against what he viewed as the degenerative effect of Hermetic ideas, particularly those of the Sabians, and was effective in persuading many Jewish thinkers away from Hermetic integration, known as Hebrew Hermetism.

Scholars, such as Abraham ibn Ezra, felt justified in invoking the authority of Hermes to offer esoteric explanations of Jewish ritual. This culminated in a wide use of Hermetic texts for the use of theurgy and talisman construction. The Jewish version of the theurgic practice of drawing divine spirits down to Earth was horadat haruhaniyut, "the lowering of spirituality." Books such as the Sefer Mafteah Shlomoh, Sefer Meleket Muskelet, Sefer ha-Tamar and Sefer Hermes. The Hermetic texts most valued by Jewish scholars were those which dealt with astrology, medicine, and astral magic; however shunned by Maimonides as dangerous and destructive.

Renaissance

Despite Maimonides' denunciation of Hermetism, Jewish scholars in the Renaissance struggled to reconcile his beliefs with those of the proponents of Hermetic thought within Judaism. Renaissance scholars argued that the rationalism of Maimonides drew upon the prisca sapienta that had both Mosaic and Hermetic origins and that Abraham ibn Ezra's Commentary on the Pentateuch was evidence that they shared the same views on the relationship between religion and science.

However, scholars such as Averroist Elijah del Medigo carried on Maimonides' crusade. Medigo claimed that the theurgic practices of Hermetism were against the teachings of the Torah. Others, such as Yohanan Alemanno, claimed that the Hermetic teachings were part of a primordial wisdom of the ancients and put the writings of Hermes as being equal to those of King Solomon. Hermetism was also prominent in the works of David Messer Leon, Isaac Abravanel, Judah Abravanel, Elijah Hayyim, Abraham Farissol, Judah Moscato and Abraham Yagel.

The works of Baruch Spinoza have also been ascribed a Hermetic element and Hermetic influenced thinkers such as Johann Wolfgang von Goethe have accepted Spinoza's version of God.

Christianity

Christianity and Hermetism have interacted in such a way that controversy surrounds the nature of the influence. Some, such as Richard August Reitzenstein believed that Hermetism had heavily influenced Christianity; while others, such as Marie-Joseph LaGrange, believed that Christianity heavily influenced Hermetism; most see the exchange as more mutual.

According to Mary E. Lyman, both religions hold redemption, revelation and focus on the knowledge of God as the meaning of humanity's existence. This knowledge of God comes upon a mystical experience dependent upon rebirth, the focal point of arguments for influence from one of these religions upon the other. The focus of this rebirth are the words "Life," "Light," and "Truth" as well as a moral attitude of the seeker in his attainment of higher knowledge. Both also share a dualistic philosophy which comes from a shared philosophical background in popular schools of Hellenistic thought. Early Christianity and Hermetism both are esoteric without having an excessive emphasis on secrecy, relying upon inward experience, assisted by instruction and ultimately the result of revelation by God.

The Fourth Gospel

Lyman also sees important similarities between the Fourth Gospel, or Gospel of John, and the Corpus Hermeticum, in religious thought and religious questing. However, she points out that there are some deep differences as well.

In Lyman's analysis, both texts utilize the concept of Logos and emphasize that the followers of their respective religions are apart from the rest of the world, suitable for only a few followers. Each of the two texts stress the importance of redemption, revelation, and rebirth to find knowledge of God and contain striking similarity in the wording of how moral attitudes promote higher knowledge in general. Opposed to the basis of the contemporary mystery cults, both texts relayed that the core of religious practice should be done internally through the personal experience of the believer rather than externally through sacramental ritual. Dualism plays a strong part in each of the two works.

Lyman also points out four distinct contrasts between the two works despite their similarities. First, that the Fourth Gospel is a homogeneous work while the Corpus Hermeticum is a work which is found in fragments which she suspects were written by many authors over a wide range of time. Second, cosmic speculation is paramount to the Hermetic work while the fourth Gospel focuses on issues of religion. Third, the Hermetic text focuses on the asceticism of the day while the Fourth Gospel ignores it completely. Fourth, the Gospel's figures are all unique and grounds itself in the life of Jesus of Nazareth while the Hermetic text uses an "elusive literary tradition" which does little to identify or separate its characters. Though she relays that a scholar named Angus believed that the two would be more similar if they had the same proportion of Hermetic writings as Christian writings.

Mormonism

A theory by John L. Brooke, an author and professor at Tufts University, suggests that Mormonism has its roots in Hermetism and Hermeticism after following a philosophical trail from Renaissance Europe. The early Mormons, most notably Joseph Smith, were linked by Brooke with magic, alchemy, Freemasonry, divining and "other elements of radical religion" prior to Mormonism. Brooke attested correlations with the view that spirit and matter are one and the same, the covenant of celestial marriage, and the ability of humanity to become deified or ultimately perfect.

Further, Brooke argued that Mormonism can only be understood in conjunction with the occult and the Reformation-era sectarian idea of restoration. He sees ties to Hermeticism in Mormon support for Pelagianism, communitarianism, polygamy and Dispensationalism.

However, Philip I. Barlow has criticized Brooke's work as carelessly seeking out relations to Hermeticism which Brooke knows better than Mormonism, and believes that Brooke's links to Hermeticism can be explained away with "a particular and selectively literal reading of the Bible."

References

- Quispel 1992.

- Van den Broek 1998, p. 17.

- Van den Broek 1998, p. 1.

- Van den Broek 1998, p. 6.

- Van den Broek 1998, p. 7.

- Van den Broek 1998, p. 8.

- Van den Broek 1998, pp. 12–13.

- Van den Broek 1998, pp. 9–10.

- Van den Broek 1998, pp. 11–12.

- Van den Broek 1998, pp. 16–17.

- Van Bladel 2009, pp. 64-114 (see especially the conclusion, pp. 113-114).

- Van Bladel 2009, pp. 164-172 et passim.

- ^ Lelli 2007.

- ^ Leslie 1999.

- Regardie 1940, p. 15.

- Wieczynski 1975, p. 22.

- Skalli 2007.

- Weststeijn 2007.

- Lange 2007.

- ^ Lyman 1930, p. 265.

- ^ Lyman 1930, p. 268.

- ^ Lyman 1930, p. 269.

- Lyman 1930, p. 271.

- Lyman 1930, p. 266.

- Lyman 1930, p. 270.

- Lyman 1930, pp. 270–71.

- ^ Lyman 1930, p. 272.

- Lyman 1930, pp. 273–74.

- Lyman 1930, pp. 274–75.

- Lyman 1930, p. 275.

- Lyman 1930, p. 273.

- ^ Barlow 1996.

Works cited

- Barlow, Philip I. (January 17, 1996). "The Refiner's Fire: The Making of Mormon Cosmology, 1644-1844". The Christian Century.

- Lange, Horst (January 1, 2007). "Das Weltbild des jungen Goethe, Band I: Elemente und Fundamente". Goethe Yearbook (in German). doi:10.1515/9781571137395-012.

- Lelli, Fabrizio (December 22, 2007). "Hermes Among the Jews: Hermetica as Hebraica from Antiquity to the Renaissance". Magic, Ritual, and Witchcraft. 2 (2): 111–135. doi:10.1353/mrw.0.0006.

- Leslie, Arthur M. (September 22, 1999). "Jews at the Time of the Renaissance". Renaissance Quarterly. 52 (3): 845–856. doi:10.2307/2901921. JSTOR 2901921.

- Lyman, Mary Ely (1930). "Hermetic Religion and the Religion of the Fourth Gospel". Journal of Biblical Literature. 49 (3): 265–276. doi:10.2307/3259049. JSTOR 3259049.

- Quispel, Gilles (March 1992). "Hermes Trismegistus and the Origins of Gnosticism". Vigiliae Christianae. 46 (1): 1–19. doi:10.2307/1583880. JSTOR 1583880.

- Regardie, Israel (1940). The Golden Dawn. St. Paul: Llewellyn Publications.

- Skalli, Cedric Cohen (January 1, 2007). "Discovering Isaac Abravanel's Humanistic Rhetoric". The Jewish Quarterly Review. 97: 67–99. doi:10.1353/jqr.2007.0007.

- Van Bladel, Kevin (2009). The Arabic Hermes: From Pagan Sage to Prophet of Science. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Van den Broek, Roel (1998). "Gnosticism and Hermetism in Antiquity". In Van den Broek, Roel; Hanegraaff, Wouter (eds.). Gnosis and Hermeticism from Antiquity to Modern Times. Albany: State University of New York Press. ISBN 0-7914-3612-8.

- Weststeijn, Thijs (October 1, 2007). "Spinoza Sinicus: an Asian Paragraph in the History of the Radical Enlightenment". Journal of the History of Ideas. 68 (4): 537–561. doi:10.1353/jhi.2007.0037.

- Wieczynski, Joseph L. (Spring 1975). "Hermetism and Cabalism in the Heresy of the Judaizers". Renaissance Quarterly. 28 (1): 17–28. doi:10.2307/2860419. JSTOR 2860419.

Further reading

- Butler, Jon (April 1979), "Magic, Astrology, and the Early American Religious Heritage", The American Historical Review, 84 (2): 317–346, doi:10.2307/1855136, JSTOR 1855136, PMID 11610526

- Candela, Giuseppe (Autumn 1998), "An Overview of the Cosmology, Religion and Philosophical Universe of Giordano Bruno", Italica, 75 (3): 348–364, doi:10.2307/480055, JSTOR 480055

- Harrie, Jeanne (Winter 1978), "Duplessis-Mornay, Foix-Candale and the Hermetic Religion of the World", Renaissance Quarterly, 31 (4): 499–514, doi:10.2307/2860375, JSTOR 2860375