In high-speed flight, the assumptions of incompressibility of the air used in low-speed aerodynamics no longer apply. In subsonic aerodynamics, the theory of lift is based upon the forces generated on a body and a moving gas (air) in which it is immersed. At airspeeds below about 260 kn (480 km/h; 130 m/s; 300 mph), air can be considered incompressible in regards to an aircraft, in that, at a fixed altitude, its density remains nearly constant while its pressure varies. Under this assumption, air acts the same as water and is classified as a fluid.

Subsonic aerodynamic theory also assumes the effects of viscosity (the property of a fluid that tends to prevent motion of one part of the fluid with respect to another) are negligible, and classifies air as an ideal fluid, conforming to the principles of ideal-fluid aerodynamics such as continuity, Bernoulli's principle, and circulation. In reality, air is compressible and viscous. While the effects of these properties are negligible at low speeds, compressibility effects in particular become increasingly important as airspeed increases. Compressibility (and to a lesser extent viscosity) is of paramount importance at speeds approaching the speed of sound. In these transonic speed ranges, compressibility causes a change in the density of the air around an airplane.

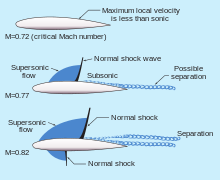

During flight, a wing produces lift by accelerating the airflow over the upper surface. This accelerated air can, and does, reach supersonic speeds, even though the airplane itself may be flying at a subsonic airspeed (Mach number < 1.0). At some extreme angles of attack, in some airplanes, the speed of the air over the top surface of the wing may be double the airplane's airspeed. It is, therefore, entirely possible to have both supersonic and subsonic airflows on an airplane at the same time. When flow velocities reach sonic speeds at some locations on an airplane (such as the area of maximum camber on the wing), further acceleration will result in the onset of compressibility effects such as shock wave formation, drag increase, buffeting, stability, and control difficulties. Subsonic flow principles are invalid at all speeds above this point.

See also

References

Sources

- Pilot's Handbook of Aeronautical Knowledge. U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington D.C.: U.S. Federal Aviation Administration. 2003. pp. 3–35. FAA-8083-25.

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from Pilot's Handbook of Aeronautical Knowledge. United States Government.

This article incorporates public domain material from Pilot's Handbook of Aeronautical Knowledge. United States Government.

This aviation-related article is a stub. You can help Misplaced Pages by expanding it. |