During most of Chile's history, from 1500 to the present, mining has been an important economic activity. 16th century mining was oriented towards the exploitation of gold placer deposits using encomienda labour. After a period of decline in the 17th century, mining resurged in the 18th and early 19th century, this time concentrating chiefly on silver. In the 1870s silver mining declined sharply. Chile took over the highly lucrative saltpetre mining districts of Peru and Bolivia in the War of the Pacific (1879–83). In the first half of the 20th century copper mining overshadowed the declining saltpetre mining.

Pre-Hispanic mining

See also: Incas in Central ChileIncas exploited placer gold in the northern half of Chile prior to the arrival of the Spanish. It has been claimed that the Inca Empire expanded into Diaguita lands because of its mineral wealth. This hypothesis was as of 1988 under dispute. An expansion of this hypothesis is that the Incas would have invaded the relatively well-populated Eastern Diaguita valleys (present-day Argentina) to obtain labour to send to Chilean mining districts.

Archaeologists Tom Dillehay and Américo Gordon claim Incan yanakuna extracted gold south of the Incan frontier in free Mapuche territory. Following this thought, the main motive for Incan expansion into Mapuche territory would have been to access gold mines.

About 74 km northeast of Copiapó in Viña del Cerro the Incas had one of its largest mining and mellargy centres at Qullasuyu. There is evidence of gold, silver and copper metallurgy at the site, including the production of bronze.

Besides gold, indigenous people in Chile also mined native copper and copper minerals, producing copper bracelets, earrings and weapons. The use of copper in Chile can be traced to 500 BC. While Pre-Hispanic Mapuche tools are known to have been relatively simple and made of wood and stone, a few them were made of copper and bronze.

Colonial mining (1541–1810)

Early Spaniards extracted gold from placer deposits using indigenous labour. This contributed to cause the Arauco War, as native Mapuches lacked a tradition of forced labour like the Andean mita and largely refused to serve the Spanish. The key area of the Arauco War were the valleys around Cordillera de Nahuelbuta where the Spanish designs for this region was to exploit the placer deposits of gold using unfree Mapuche labour from the nearby and densely populated valleys. Deaths related to mining contributed to a population decline among native Mapuches. Another site of Spanish mining was the city of Villarrica. Here the Spanish mined gold placers and silver. The original site of the city was likely close to modern Pucón. However at some point in the 16th century it is presumed the gold placers were buried by lahars flowing down from nearby Villarrica volcano. This prompted settlers to relocate the city further west at its modern location.

While of less importance than gold districts in the south, the Spanish also carried out mining operations in Central Chile. There the whole economy was oriented towards mining. As indigenous populations in Central Chile declined to about 30% of their 1540s numbers towards the end of the 16th century and gold deposits became depleted, the Spanish of Central Chile begun to focus on livestock operations.

Mining activity declined in the late 16th century as the richest placer deposits, which are usually the most shallow, became exhausted. The decline was aggravated by the collapse of the Spanish cities in the south following the battle of Curalaba (1598) which meant for the Spaniards the loss of both the main gold districts and the largest indigenous labour sources. Gold mining became a taboo among Mapuches in colonial times, and gold mining often prohibited under the death penalty.

Compared to the 16th and 18th centuries, Chilean mining activity in the 17th century was very limited. Gold production totaled as little as 350 kg over the whole century. Chile exported minor amounts of copper to the rest of the Viceroyalty of Peru in the 17th century. But Chile saw an unprecedented revival of its mining activity in the 18th century, with annual gold production rising from 400 to 1000 kg over the course of the century and annual silver production rising from 1000 to 5000 kg in the same interval. Chilean copper mining of high-grade oxidized copper minerals and melted with charcoal produced 80,000 to 85,000 tons of copper in the 1541–1810 period.

Gold, silver and copper from Chilean mining begun to be exported directly to Spain via the Straits of Magellan and Buenos Aires in the 18th century.

By the first half of the 18th century sulfur was being mined from the extinct volcanoes in the Andes around Copiapó. This element was crucial for the fabrication of gunpowder.

Early Spanish conquistadores and explorers knew there was coal in Chilean territory. For example, Diego de Rosales noted that when governor García Hurtado de Mendoza and his men stayed in Quiriquina Island (36.5° S) in 1557 they made fire using local coals. In Magallanes Region coal was first discovered by the expedition of Pedro Sarmiento de Gamboa who visited the Straits of Magellan in 1584.

Silver rushes and early coal mining (1810–1870)

Following the discovery of silver at Agua Amarga (1811) and Arqueros (1825) the Norte Chico mountains north of La Serena (part of the Chilean Iron Belt) were exhaustively prospected. In 1832 prospector Juan Godoy found a silver outcrop (reventón) 50 km south of Copiapó in Chañarcillo. The finding attracted thousands of people to the place and generated significant wealth. After the discovery of Chañarcillo, many other ores were discovered near Copiapó well into the 1840s. Copiapó experienced a large demographic and urbanistic growth during the rush. The town became a centre for trade and services of a large mining district. The mining zone slowly grew northwards into the diffuse border with Bolivia. At the end of the silver rush rich miners had diversified their assets into banking, agriculture, trade and commerce all over Chile.

A last major discovery of silver occurred 1870 in Caracoles in Bolivian territory adjacent to Chile. Apart from being discovered by Chileans, the ore was also extracted with Chilean capital and miners.

In the 19th century Claudio Gay and Benjamín Vicuña Mackenna were among the first to raise the question of the deforestation of Norte Chico caused by the firewood demands of the mining activity. Despite the reality of the degradation caused by mining, and contrary to popular belief, the Norte Chico forests were not pristine, even before the onset of mining in the 18th century. Salpeter mining in Tarapacá, then part of Peru, also caused a degradation of the arid forests of Pampa del Tamarugal. The rustic mineral processing using the paradas method demanded great amounts of firewood, leading to large-scale deforestation around La Tirana and Canchones and some areas to the south of those localities.

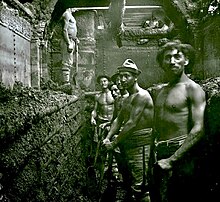

Besides silver, coal mining also boomed in the early republican period. As coal mining was commonplace in industrialised, Britain early British travellers had the opportunity to comment on Chilean coals before they were profitable. British travelers had differing opinions on the economic value of Chilean coals, or more specifically, the coals of Zona Central Sur (36–38 °S). While David Barry found the coals to be of good quality, Charles Darwin held them of to be of little value. The British consul in Chile correctly predicted in 1825 that the area around the mouth of Biobío River would be a centre of the coal industry. It was however not until the mid-19th century that large scale coal mining began in the region. The initial trigger of coal mining was the arrival of steamships at the port of Talcahuano. These steam ships, most of which were English, initially bought the coal very cheaply, and the exploited coal seams were easy to work as they lay almost at ground level. Demand for coal stemmed not only from steam navigation, but also from the growth of copper mining in northern Chile. As wood became increasingly scarce in northern Chile, copper smelters resorted to the coals found around Zona Central Sur. Demand from copper smelters in the 1840s proved crucial to stabilising the coal business.

Coal mining operations were chiefly owned by Chilean businessmen, contrasting with the heavy foreign involvement in silver mining and later also in saltpetre and copper mining. Silver mining and coal mining were somewhat linked by Matías Cousiño, a silver mining magnate who expanded into the coal business. Cousiño began mining operations in Lota in 1852, a move that rapidly transformed the town from a sparsely populated frontier zone in the mid-19th century, into a large industrial hub that attracted immigrants from all over Chile well into the 20th century.

Saltpetre era (1870–1930)

Starting in 1873, Chile's economy deteriorated. Several of Chile's key exports were out-competed and Chile's silver mining income dropped. In the mid-1870s, Peru nationalized its nitrate industry, affecting both British and Chilean interests. Contemporaries considered the crisis the worst ever in independent Chile. Chilean newspaper El Ferrocarril predicted 1879 to be "a year of mass business liquidation". In 1878, President Aníbal Pinto expressed his concern in the following statement:

If a new mining discovery or some novelty of that sort does not come to improve the actual situation, the crisis that has long been felt will worsen

— Aníbal Pinto, president of Chile, 1878.

During this economic crisis, Chile became involved in the costly Saltpetre War (1879–1883) and gained control of mineral-rich provinces of Peru and Bolivia. The notion that Chile entered the war to obtain economical gains has been a topic of debate among historians.

As the victor and possessor of a new coastal territory following the War of the Pacific, Chile benefited by gaining a lucrative territory with significant mineral income. The national treasury grew by 900 percent between 1879 and 1902, due to taxes from the newly acquired lands. British involvement and control of the nitrate industry rose significantly, but from 1901 to 1921 Chilean ownership increased from 15% to 51%. The growth of the Chilean economy benefited from its saltpetre monopoly. Thus, compared to the previous growth cycle (1832–1873), the economy became less diversified and overly dependent on a single natural resource. In addition the Chilean nitrate, used worldwide as fertilizer, was sensitive to economic downturns as farmers reduced their use of made cuts on fertilizer, as one of their earliest economic measures in the face of economic decline. It has been questioned whether the nitrate wealth conquered in the War of the Pacific was a resource curse or not. During the Nitrate Epoch the government increased public spending, but was nevertheless accused of squandering money.

When conquering Peruvian territories in 1880 Chile imposed a tax of 1.6 Chilean peso on each quintal (0.1 ton) exported. This tax made saltpetre more expensive on a global scale; in other words it was a "tax exportation". In the 1920s this tax begun to be considered obsolete by Chilean politicians. A new mining code was enacted in 1888.

From 1876 to 1891 Chilean copper mining declined, being largely replaced in international markets by copper from the United States and Río Tinto in Spain. This was in part due to the exhaustion of supergene (shallow) high-grade ores. The introduction of new extraction techniques and technology in the early 20th century contributed to a significant resurgence of copper mining. Technological innovation in drilling, blasting, loading and transport made it profitable to mine large low-grade porphyry copper deposits.

Copper era (1930–2010)

| This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (October 2015) |

In the 1910s the main copper mining countries were Chile, Spain and the United States. The tax obtained from copper mining amounted to "little or nothing". In the 1950s the taxation of copper mining was reformed. In 1932 a new mining code replaced the older code of 1888.

The Law on Mining Concessions was reformed in 1982, moving mining concessions rights away from the ad coelum principle.

Investments in mineral exploration in Chile reached a maximum in 1997 and declined from then on until 2003. Thus by 2004 there were relatively few active mining projects. From 1995 to 2004 the principal discoveries were the copper porphyries of Escondida and Toki. In addition, in the 1995–2004 period a larger group of medium-sized mineral deposits (with non-mineralized cover rocks) were discovered, including Candelaria, El Peñón, Gaby Sur, Pascua Lama and Spence.

By 2004, the number of companies involved in exploration had diminished due to mergers.

Chile was, in 2019, the world's largest producer of copper, iodine and rhenium, the second largest producer of lithium and molybdenum, the sixth largest producer of silver, the seventh largest producer of salt, the eighth largest producer of potash, the thirteenth producer of sulfur and the thirteenth producer of iron ore in the world. The country also has considerable gold production: between 2006 and 2017, the country produced annual amounts ranging from 35.9 tonnes in 2017 to 51.3 tonnes in 2013.

References

- ^ Maksaev, Víctor; Townley, Brian; Palacios, Carlos; Camus, Francisco (2006). "6. Metallic ore deposits". In Moreno, Teresa; Gibbons, Wes (eds.). Geology of Chile. Geological Society of London. pp. 179–180. ISBN 9781862392199.

- ^ Lorandi, A.M. (1988). "Los diaguitas y el tawantinsuyu: Una hipótesis de conflicto". In Dillehay, Tom; Netherly, Patricia (eds.). La frontera del estado Inca (in Spanish). pp. 197–214.

- Dillehay, T.; Gordon, A. (1988). "La actividad prehispánica y su influencia en la Araucanía". In Dillehay, Tom; Netherly, Patricia (eds.). La frontera del estado Inca (in Spanish). pp. 183–196.

- ^ Cortés Lutz, Guillermo (2017). Chañarcillo, cuando de las montañas brotó la plata (PDF). Cuadernos de Historia (in Spanish). Vol. II. Museo Regional de Atacama. p. 4.

- Villalobos et al. 1974, p. 50.

- Bengoa 2003, pp. 190–191.

- Mariño de Lobera, Pedro (1960). "XLIII". Crónica del Reino de Chile (in Spanish).

...hicieron con él muchas fiestas por burla y escarnio, y por remate trajeron una olla de oro ardiendo y se la presentaron, diciéndole: pues tan amigo eres de oro, hártate agora dél, y para que lo tengas más guardado, abre la boca y bebe aqueste que viene fundido, y diciendo esto lo hicieron como lo dijeron, dándoselo a beber por fuerza, teniendo por fin de su muerte lo que tuvo por fin de su entrada en Chile

- ^ Bengoa, José (2003). Historia de los antiguos mapuches del sur (in Spanish). Santiago: Catalonia. pp. 252–253. ISBN 956-8303-02-2.

- Zavala C., José Manuel (2014). "The Spanish-Araucanian World of the Purén and Lumaco Valley in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries". In Dillehay, Tom (ed.). The Teleoscopic Polity. Springer. pp. 55–73. ISBN 978-3-319-03128-6.

- ^ Petit-Breuilh 2004, pp. 48–49.

- Contreras Cruces, Hugo (2016). "Migraciones locales y asentamiento indígena en las estancias españolas de Chile central, 1580-1650". Historia (in Spanish). 49 (1): 87–110. doi:10.4067/S0717-71942016000100004.

- *Salazar, Gabriel; Pinto, Julio (2002). Historia contemporánea de Chile III. La economía: mercados empresarios y trabajadores (in Spanish). LOM Ediciones. p. 15. ISBN 956-282-172-2

- Payàs Puigarnau, Getrudis; Villena Araya, Belén (2021-12-15). "Indagaciones en torno al significado del oro en la cultura mapuche. Una exploración de fuentes y algo más" [Inquiries on the Meaning of Gold in Mapuche Culture. A review of sources and something more]. Estudios Atacameños (in Spanish). 67. doi:10.22199/issn.0718-1043-2021-0028. S2CID 244279716.

- Villalobos et al. 1974, p. 168.

- Villalobos, Sergio; Retamal Ávila, Julio; Serrano, Sol (2000). Historia del pueblo Chileno (in Spanish). Vol. 4. p. 154.

- Villalobos et al. 1974, pp. 226–227.

- Salazar & Pinto 2002, pp. 16–17.

- Petit-Breuilh 2004, p. 55.

- Petit-Breuilh 2004, p. 44.

- ^ Davis, Eliodoro Martín (1990). "Breves recuerdos de algunas actividades mineras del carbón". Actas. Segundo Simposio sobre el Terciario de Chile (in Spanish). Santiago, Chile: Departamento de Geociencias, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad de Concepción. pp. 189–203.

- Martinic, Mateo (2004). "La minería del carbón en Magallanes entre 1868 - 2003". Historia (in Spanish). 31 (1): 129–167.

- ^ Villalobos et al. 1974, pp. 469–472.

- ^ Los ciclos mineros del cobre y la plata. Memoria Chilena.

- ^ Bethell, Leslie. 1993. Chile Since Independence. Cambridge University Press. p. 13–14.

- "Los Ciclos Mineros del Cobre y la Plata (1820-1880)" [Mining Cycles of Copper and Silver]. Memoria Chilena (in Spanish). Biblioteca Nacional de Chile. Archived from the original on 31 December 2013.

- Camus Gayan, Pablo (2004). "Los bosques y la minería del Norte Chico, S. XIX. Un mito en la representación del paísaje chileno" (PDF). Historia (in Spanish). 37 (II): 289–310. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 25 October 2015.

- Castro Castro, Luis (2020-07-01). "El bosque de la Pampa del Tamarugal y la industria salitrera: El problema de la deforestación, los proyectos para su manejo sustentable y el debate político (Tarapacá, Peru-Chile 1829-1941)" [The Forest of Pampa del Tamarugal and the Saltpeter Industry: The Deforestation Problem, the Projects for their Sustainable Management and the Political Debate (Tarapacá, Perú-Chile 1829-1941)]. Scripta Nova (in Spanish). XXIV (641). Universitat de Barcelona.

- ^ Mazzei de Grazia, Leonardo (1997). "Los Británicos y el carbón en Chile" (PDF). Atenea (in Spanish): 137–167.

- Endlicher, Wilfried. 1986. Desarrollo Histórico-genético y División Funcional del Centro Carbonífero. Revista de Geografía Norte Grande.

- ^ Vivallos Espinoza, Carlos; Brito Peña, Alejandra (2010). "Inmigración y sectores populares en las minas de carbón de Lota y Coronel (Chile 1850-1900)" [Immigration and popular sectors in the coal mines of Lota and Coronel (Chile 1850-1900)]. Atenea (in Spanish). 501: 73–94.

- Ortega, Luis (1982). "The First Four Decades of the Chilean Coal Mining Industry, 1840-1879". Journal of Latin American Studies. 14 (1): 1–32. doi:10.1017/S0022216X00003564.

- Mazzei, Leonardo (2000). "Expansión de gestiones empresariales desde la minería del norte a la del carbón, Chile, siglo XIX" (PDF). Historia (in Spanish). 46: 91–102.

- ^ Palma, Gabriel. Trying to 'Tax and Spend' Oneself out of the 'Dutch Disease': The Chilean Economy from the War of the Pacific to the Great Depression. p. 217–240

- ^ Salazar & Pinto 2002, pp. 25–29.

- Villalobos et al. 1974, pp. 6003-605.

- Ortega, Luis (1984). "Nitrates, Chilean Entrepreneurs and the Origins of the War of the Pacific". Journal of Latin American Studies. 16 (2): 337–380. doi:10.1017/S0022216X00007100.

- Sater, William F. (1973). "Chile During the First Months of the War of the Pacific". 5, 1 (pages 133-138 ed.). Cambridge at the University Press: Journal of Latin American Studies: 37.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Crow, The Epic of Latin America, p. 180

- Foster, John B. & Clark, Brett. (2003). "Ecological Imperialism: The Curse of Capitalism" (accessed September 2, 2005). The Socialist Register 2004, p190–192. Also available in print from Merlin Press.

- Salazar & Pinto 2002, pp. 124-125.

- ^ Brown, J. R. (1963), "Nitrate Crises, Combinations, and the Chilean Government in the Nitrate Age.", The Hispanic American Historical Review, 43 (2): 230–246, doi:10.2307/2510493, JSTOR 2510493

- Ducoing Ruiz, C. A.; Miró, M. B. (2012), Avoiding the Dutch disease? The Chilean industrial sector in the nitrate trade cycle. 1870–1938. (PDF)

- ^ Wagner, Gert (2005). "Un siglo de tributación minera". In Lagos, Gustavo (ed.). Minería y desarrollo (in Spanish). Santiago, Chile: Ediciones Universidad Católica de Chile. pp. 193–227. ISBN 956-14-0844-9.

- ^ Camus, Francisco (2005). "La minería y la evolución de la exploración en Chile". In Lagos, Gustavo (ed.). Minería y desarrollo (in Spanish). Santiago, Chile: Ediciones Universidad Católica de Chile. pp. 229–270. ISBN 956-14-0844-9.

- Ley Orgánica Constitucional sobre Concesiones Mineras (in Spanish), Biblioteca del Congreso Nacional de Chile, retrieved December 18, 2013

- "USGS Copper Production Statistics" (PDF).

- "USGS Iodine Production Statistics" (PDF).

- "USGS Rhenium Production Statistics" (PDF).

- "USGS Lithium Production Statistics" (PDF).

- "USGS Molybdenum Production Statistics" (PDF).

- "USGS Silver Production Statistics" (PDF).

- "USGS Salt Production Statistics" (PDF).

- "USGS Potash Product ion Statistics" (PDF).

- "USGS Sulfur Production Statistics" (PDF).

- "USGS Iron Ore Production Statistics" (PDF).

- Gold Production in Chile

Bibliography

- Bengoa, José (2003). Historia de los antiguos mapuches del sur (in Spanish). Santiago: Catalonia. ISBN 956-8303-02-2.

- Salazar, Gabriel; Pinto, Julio (2002). Historia contemporánea de Chile III. La economía: mercados empresarios y trabajadores. LOM Ediciones. ISBN 956-282-172-2.

- Petit-Breuilh Sepúlveda, María Eugenia (2004). "Los volcanes y la evolución del poblamiento". La historia eruptiva de los volcanes hispanoamericanos (Siglos XVI al XX): El modelo chileno (in Spanish). Huelva, Spain: Casa de los volcanes. ISBN 84-95938-32-4.

- Villalobos, Sergio; Silva, Osvaldo; Silva, Fernando; Estelle, Patricio (1974). Historia De Chile (14th ed.). Editorial Universitaria. ISBN 956-11-1163-2.

| Chile articles | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History |

|  | |||||||||

| Geography | |||||||||||

| Politics |

| ||||||||||

| Economy | |||||||||||

| Society |

| ||||||||||