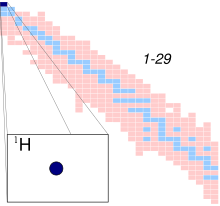

| |

| General | |

|---|---|

| Symbol | H |

| Names | hydrogen atom, 1H, H-1, protium |

| Protons (Z) | 1 |

| Neutrons (N) | 0 |

| Nuclide data | |

| Natural abundance | 99.985% |

| Half-life (t1/2) | stable |

| Isotope mass | 1.007825 Da |

| Spin | 1/2 |

| Excess energy | 7288.969±0.001 keV |

| Binding energy | 0.000±0.0000 keV |

| Isotopes of hydrogen Complete table of nuclides | |

A hydrogen atom is an atom of the chemical element hydrogen. The electrically neutral hydrogen atom contains a single positively charged proton in the nucleus, and a single negatively charged electron bound to the nucleus by the Coulomb force. Atomic hydrogen constitutes about 75% of the baryonic mass of the universe.

In everyday life on Earth, isolated hydrogen atoms (called "atomic hydrogen") are extremely rare. Instead, a hydrogen atom tends to combine with other atoms in compounds, or with another hydrogen atom to form ordinary (diatomic) hydrogen gas, H2. "Atomic hydrogen" and "hydrogen atom" in ordinary English use have overlapping, yet distinct, meanings. For example, a water molecule contains two hydrogen atoms, but does not contain atomic hydrogen (which would refer to isolated hydrogen atoms).

Atomic spectroscopy shows that there is a discrete infinite set of states in which a hydrogen (or any) atom can exist, contrary to the predictions of classical physics. Attempts to develop a theoretical understanding of the states of the hydrogen atom have been important to the history of quantum mechanics, since all other atoms can be roughly understood by knowing in detail about this simplest atomic structure.

Isotopes

Main article: Isotopes of hydrogenThe most abundant isotope, protium (H), or light hydrogen, contains no neutrons and is simply a proton and an electron. Protium is stable and makes up 99.985% of naturally occurring hydrogen atoms.

Deuterium (H) contains one neutron and one proton in its nucleus. Deuterium is stable, makes up 0.0156% of naturally occurring hydrogen, and is used in industrial processes like nuclear reactors and Nuclear Magnetic Resonance.

Tritium (H) contains two neutrons and one proton in its nucleus and is not stable, decaying with a half-life of 12.32 years. Because of its short half-life, tritium does not exist in nature except in trace amounts.

Heavier isotopes of hydrogen are only created artificially in particle accelerators and have half-lives on the order of 10 seconds. They are unbound resonances located beyond the neutron drip line; this results in prompt emission of a neutron.

The formulas below are valid for all three isotopes of hydrogen, but slightly different values of the Rydberg constant (correction formula given below) must be used for each hydrogen isotope.

Hydrogen ion

Main articles: hydrogen cation and hydrogen anionLone neutral hydrogen atoms are rare under normal conditions. However, neutral hydrogen is common when it is covalently bound to another atom, and hydrogen atoms can also exist in cationic and anionic forms.

If a neutral hydrogen atom loses its electron, it becomes a cation. The resulting ion, which consists solely of a proton for the usual isotope, is written as "H" and sometimes called hydron. Free protons are common in the interstellar medium, and solar wind. In the context of aqueous solutions of classical Brønsted–Lowry acids, such as hydrochloric acid, it is actually hydronium, H3O, that is meant. Instead of a literal ionized single hydrogen atom being formed, the acid transfers the hydrogen to H2O, forming H3O.

If instead a hydrogen atom gains a second electron, it becomes an anion. The hydrogen anion is written as "H" and called hydride.

Theoretical analysis

The hydrogen atom has special significance in quantum mechanics and quantum field theory as a simple two-body problem physical system which has yielded many simple analytical solutions in closed-form.

Failed classical description

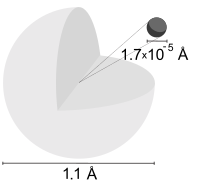

Experiments by Ernest Rutherford in 1909 showed the structure of the atom to be a dense, positive nucleus with a tenuous negative charge cloud around it. This immediately raised questions about how such a system could be stable. Classical electromagnetism had shown that any accelerating charge radiates energy, as shown by the Larmor formula. If the electron is assumed to orbit in a perfect circle and radiates energy continuously, the electron would rapidly spiral into the nucleus with a fall time of: where is the Bohr radius and is the classical electron radius. If this were true, all atoms would instantly collapse. However, atoms seem to be stable. Furthermore, the spiral inward would release a smear of electromagnetic frequencies as the orbit got smaller. Instead, atoms were observed to emit only discrete frequencies of radiation. The resolution would lie in the development of quantum mechanics.

Bohr–Sommerfeld Model

Main article: Bohr modelIn 1913, Niels Bohr obtained the energy levels and spectral frequencies of the hydrogen atom after making a number of simple assumptions in order to correct the failed classical model. The assumptions included:

- Electrons can only be in certain, discrete circular orbits or stationary states, thereby having a discrete set of possible radii and energies.

- Electrons do not emit radiation while in one of these stationary states.

- An electron can gain or lose energy by jumping from one discrete orbit to another.

Bohr supposed that the electron's angular momentum is quantized with possible values: where and is Planck constant over . He also supposed that the centripetal force which keeps the electron in its orbit is provided by the Coulomb force, and that energy is conserved. Bohr derived the energy of each orbit of the hydrogen atom to be: where is the electron mass, is the electron charge, is the vacuum permittivity, and is the quantum number (now known as the principal quantum number). Bohr's predictions matched experiments measuring the hydrogen spectral series to the first order, giving more confidence to a theory that used quantized values.

For , the value is called the Rydberg unit of energy. It is related to the Rydberg constant of atomic physics by

The exact value of the Rydberg constant assumes that the nucleus is infinitely massive with respect to the electron. For hydrogen-1, hydrogen-2 (deuterium), and hydrogen-3 (tritium) which have finite mass, the constant must be slightly modified to use the reduced mass of the system, rather than simply the mass of the electron. This includes the kinetic energy of the nucleus in the problem, because the total (electron plus nuclear) kinetic energy is equivalent to the kinetic energy of the reduced mass moving with a velocity equal to the electron velocity relative to the nucleus. However, since the nucleus is much heavier than the electron, the electron mass and reduced mass are nearly the same. The Rydberg constant RM for a hydrogen atom (one electron), R is given by where is the mass of the atomic nucleus. For hydrogen-1, the quantity is about 1/1836 (i.e. the electron-to-proton mass ratio). For deuterium and tritium, the ratios are about 1/3670 and 1/5497 respectively. These figures, when added to 1 in the denominator, represent very small corrections in the value of R, and thus only small corrections to all energy levels in corresponding hydrogen isotopes.

There were still problems with Bohr's model:

- it failed to predict other spectral details such as fine structure and hyperfine structure

- it could only predict energy levels with any accuracy for single–electron atoms (hydrogen-like atoms)

- the predicted values were only correct to , where is the fine-structure constant.

Most of these shortcomings were resolved by Arnold Sommerfeld's modification of the Bohr model. Sommerfeld introduced two additional degrees of freedom, allowing an electron to move on an elliptical orbit characterized by its eccentricity and declination with respect to a chosen axis. This introduced two additional quantum numbers, which correspond to the orbital angular momentum and its projection on the chosen axis. Thus the correct multiplicity of states (except for the factor 2 accounting for the yet unknown electron spin) was found. Further, by applying special relativity to the elliptic orbits, Sommerfeld succeeded in deriving the correct expression for the fine structure of hydrogen spectra (which happens to be exactly the same as in the most elaborate Dirac theory). However, some observed phenomena, such as the anomalous Zeeman effect, remained unexplained. These issues were resolved with the full development of quantum mechanics and the Dirac equation. It is often alleged that the Schrödinger equation is superior to the Bohr–Sommerfeld theory in describing hydrogen atom. This is not the case, as most of the results of both approaches coincide or are very close (a remarkable exception is the problem of hydrogen atom in crossed electric and magnetic fields, which cannot be self-consistently solved in the framework of the Bohr–Sommerfeld theory), and in both theories the main shortcomings result from the absence of the electron spin. It was the complete failure of the Bohr–Sommerfeld theory to explain many-electron systems (such as helium atom or hydrogen molecule) which demonstrated its inadequacy in describing quantum phenomena.

Schrödinger equation

The Schrödinger equation is the standard quantum-mechanics model; it allows one to calculate the stationary states and also the time evolution of quantum systems. Exact analytical answers are available for the nonrelativistic hydrogen atom. Before we go to present a formal account, here we give an elementary overview.

Given that the hydrogen atom contains a nucleus and an electron, quantum mechanics allows one to predict the probability of finding the electron at any given radial distance . It is given by the square of a mathematical function known as the "wavefunction", which is a solution of the Schrödinger equation. The lowest energy equilibrium state of the hydrogen atom is known as the ground state. The ground state wave function is known as the wavefunction. It is written as:

Here, is the numerical value of the Bohr radius. The probability density of finding the electron at a distance in any radial direction is the squared value of the wavefunction:

The wavefunction is spherically symmetric, and the surface area of a shell at distance is , so the total probability of the electron being in a shell at a distance and thickness is

It turns out that this is a maximum at . That is, the Bohr picture of an electron orbiting the nucleus at radius corresponds to the most probable radius. Actually, there is a finite probability that the electron may be found at any place , with the probability indicated by the square of the wavefunction. Since the probability of finding the electron somewhere in the whole volume is unity, the integral of is unity. Then we say that the wavefunction is properly normalized.

As discussed below, the ground state is also indicated by the quantum numbers . The second lowest energy states, just above the ground state, are given by the quantum numbers , , and . These states all have the same energy and are known as the and states. There is one state: and there are three states:

An electron in the or state is most likely to be found in the second Bohr orbit with energy given by the Bohr formula.

Wavefunction

The Hamiltonian of the hydrogen atom is the radial kinetic energy operator plus the Coulomb electrostatic potential energy between the positive proton and the negative electron. Using the time-independent Schrödinger equation, ignoring all spin-coupling interactions and using the reduced mass , the equation is written as:

Expanding the Laplacian in spherical coordinates:

This is a separable, partial differential equation which can be solved in terms of special functions. When the wavefunction is separated as product of functions , , and three independent differential functions appears with A and B being the separation constants:

- radial:

- polar:

- azimuth:

The normalized position wavefunctions, given in spherical coordinates are:

where:

- ,

- is the reduced Bohr radius, ,

- is a generalized Laguerre polynomial of degree , and

- is a spherical harmonic function of degree and order .

Note that the generalized Laguerre polynomials are defined differently by different authors. The usage here is consistent with the definitions used by Messiah, and Mathematica. In other places, the Laguerre polynomial includes a factor of , or the generalized Laguerre polynomial appearing in the hydrogen wave function is instead.

The quantum numbers can take the following values:

Additionally, these wavefunctions are normalized (i.e., the integral of their modulus square equals 1) and orthogonal: where is the state represented by the wavefunction in Dirac notation, and is the Kronecker delta function.

The wavefunctions in momentum space are related to the wavefunctions in position space through a Fourier transform which, for the bound states, results in where denotes a Gegenbauer polynomial and is in units of .

The solutions to the Schrödinger equation for hydrogen are analytical, giving a simple expression for the hydrogen energy levels and thus the frequencies of the hydrogen spectral lines and fully reproduced the Bohr model and went beyond it. It also yields two other quantum numbers and the shape of the electron's wave function ("orbital") for the various possible quantum-mechanical states, thus explaining the anisotropic character of atomic bonds.

The Schrödinger equation also applies to more complicated atoms and molecules. When there is more than one electron or nucleus the solution is not analytical and either computer calculations are necessary or simplifying assumptions must be made.

Since the Schrödinger equation is only valid for non-relativistic quantum mechanics, the solutions it yields for the hydrogen atom are not entirely correct. The Dirac equation of relativistic quantum theory improves these solutions (see below).

Results of Schrödinger equation

The solution of the Schrödinger equation (wave equation) for the hydrogen atom uses the fact that the Coulomb potential produced by the nucleus is isotropic (it is radially symmetric in space and only depends on the distance to the nucleus). Although the resulting energy eigenfunctions (the orbitals) are not necessarily isotropic themselves, their dependence on the angular coordinates follows completely generally from this isotropy of the underlying potential: the eigenstates of the Hamiltonian (that is, the energy eigenstates) can be chosen as simultaneous eigenstates of the angular momentum operator. This corresponds to the fact that angular momentum is conserved in the orbital motion of the electron around the nucleus. Therefore, the energy eigenstates may be classified by two angular momentum quantum numbers, and (both are integers). The angular momentum quantum number determines the magnitude of the angular momentum. The magnetic quantum number determines the projection of the angular momentum on the (arbitrarily chosen) -axis.

In addition to mathematical expressions for total angular momentum and angular momentum projection of wavefunctions, an expression for the radial dependence of the wave functions must be found. It is only here that the details of the Coulomb potential enter (leading to Laguerre polynomials in ). This leads to a third quantum number, the principal quantum number . The principal quantum number in hydrogen is related to the atom's total energy.

Note that the maximum value of the angular momentum quantum number is limited by the principal quantum number: it can run only up to , i.e., .

Due to angular momentum conservation, states of the same but different have the same energy (this holds for all problems with rotational symmetry). In addition, for the hydrogen atom, states of the same but different are also degenerate (i.e., they have the same energy). However, this is a specific property of hydrogen and is no longer true for more complicated atoms which have an (effective) potential differing from the form (due to the presence of the inner electrons shielding the nucleus potential).

Taking into account the spin of the electron adds a last quantum number, the projection of the electron's spin angular momentum along the -axis, which can take on two values. Therefore, any eigenstate of the electron in the hydrogen atom is described fully by four quantum numbers. According to the usual rules of quantum mechanics, the actual state of the electron may be any superposition of these states. This explains also why the choice of -axis for the directional quantization of the angular momentum vector is immaterial: an orbital of given and obtained for another preferred axis can always be represented as a suitable superposition of the various states of different (but same ) that have been obtained for .

Mathematical summary of eigenstates of hydrogen atom

Main article: Hydrogen-like atomIn 1928, Paul Dirac found an equation that was fully compatible with special relativity, and (as a consequence) made the wave function a 4-component "Dirac spinor" including "up" and "down" spin components, with both positive and "negative" energy (or matter and antimatter). The solution to this equation gave the following results, more accurate than the Schrödinger solution.

Energy levels

The energy levels of hydrogen, including fine structure (excluding Lamb shift and hyperfine structure), are given by the Sommerfeld fine-structure expression: where is the fine-structure constant and is the total angular momentum quantum number, which is equal to , depending on the orientation of the electron spin relative to the orbital angular momentum. This formula represents a small correction to the energy obtained by Bohr and Schrödinger as given above. The factor in square brackets in the last expression is nearly one; the extra term arises from relativistic effects (for details, see #Features going beyond the Schrödinger solution). It is worth noting that this expression was first obtained by A. Sommerfeld in 1916 based on the relativistic version of the old Bohr theory. Sommerfeld has however used different notation for the quantum numbers.

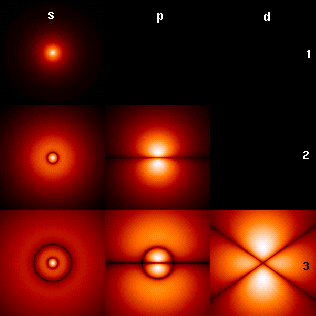

Visualizing the hydrogen electron orbitals

Main article: Atomic orbital

The image to the right shows the first few hydrogen atom orbitals (energy eigenfunctions). These are cross-sections of the probability density that are color-coded (black represents zero density and white represents the highest density). The angular momentum (orbital) quantum number ℓ is denoted in each column, using the usual spectroscopic letter code (s means ℓ = 0, p means ℓ = 1, d means ℓ = 2). The main (principal) quantum number n (= 1, 2, 3, ...) is marked to the right of each row. For all pictures the magnetic quantum number m has been set to 0, and the cross-sectional plane is the xz-plane (z is the vertical axis). The probability density in three-dimensional space is obtained by rotating the one shown here around the z-axis.

The "ground state", i.e. the state of lowest energy, in which the electron is usually found, is the first one, the 1s state (principal quantum level n = 1, ℓ = 0).

Black lines occur in each but the first orbital: these are the nodes of the wavefunction, i.e. where the probability density is zero. (More precisely, the nodes are spherical harmonics that appear as a result of solving the Schrödinger equation in spherical coordinates.)

The quantum numbers determine the layout of these nodes. There are:

- total nodes,

- of which are angular nodes:

- angular nodes go around the axis (in the xy plane). (The figure above does not show these nodes since it plots cross-sections through the xz-plane.)

- (the remaining angular nodes) occur on the (vertical) axis.

- (the remaining non-angular nodes) are radial nodes.

Oscillation of orbitals

The frequency of a state in level n is , so in case of a superposition of multiple orbitals, they would oscillate due to the difference in frequency. For example two states, ψ1and ψ2: The wavefunction is given by and the probability function is

The result is a rotating wavefunction. The movement of electrons and change of quantum states radiates light at a frequency of the cosine.

Features going beyond the Schrödinger solution

There are several important effects that are neglected by the Schrödinger equation and which are responsible for certain small but measurable deviations of the real spectral lines from the predicted ones:

- Although the mean speed of the electron in hydrogen is only 1/137th of the speed of light, many modern experiments are sufficiently precise that a complete theoretical explanation requires a fully relativistic treatment of the problem. A relativistic treatment results in a momentum increase of about 1 part in 37,000 for the electron. Since the electron's wavelength is determined by its momentum, orbitals containing higher speed electrons show contraction due to smaller wavelengths.

- Even when there is no external magnetic field, in the inertial frame of the moving electron, the electromagnetic field of the nucleus has a magnetic component. The spin of the electron has an associated magnetic moment which interacts with this magnetic field. This effect is also explained by special relativity, and it leads to the so-called spin–orbit coupling, i.e., an interaction between the electron's orbital motion around the nucleus, and its spin.

Both of these features (and more) are incorporated in the relativistic Dirac equation, with predictions that come still closer to experiment. Again the Dirac equation may be solved analytically in the special case of a two-body system, such as the hydrogen atom. The resulting solution quantum states now must be classified by the total angular momentum number j (arising through the coupling between electron spin and orbital angular momentum). States of the same j and the same n are still degenerate. Thus, direct analytical solution of Dirac equation predicts 2S(1/2) and 2P(1/2) levels of hydrogen to have exactly the same energy, which is in a contradiction with observations (Lamb–Retherford experiment).

- There are always vacuum fluctuations of the electromagnetic field, according to quantum mechanics. Due to such fluctuations degeneracy between states of the same j but different l is lifted, giving them slightly different energies. This has been demonstrated in the famous Lamb–Retherford experiment and was the starting point for the development of the theory of quantum electrodynamics (which is able to deal with these vacuum fluctuations and employs the famous Feynman diagrams for approximations using perturbation theory). This effect is now called Lamb shift.

For these developments, it was essential that the solution of the Dirac equation for the hydrogen atom could be worked out exactly, such that any experimentally observed deviation had to be taken seriously as a signal of failure of the theory.

Alternatives to the Schrödinger theory

In the language of Heisenberg's matrix mechanics, the hydrogen atom was first solved by Wolfgang Pauli using a rotational symmetry in four dimensions generated by the angular momentum and the Laplace–Runge–Lenz vector. By extending the symmetry group O(4) to the dynamical group O(4,2), the entire spectrum and all transitions were embedded in a single irreducible group representation.

In 1979 the (non-relativistic) hydrogen atom was solved for the first time within Feynman's path integral formulation of quantum mechanics by Duru and Kleinert. This work greatly extended the range of applicability of Feynman's method.

Further alternative models are Bohm mechanics and the complex Hamilton-Jacobi formulation of quantum mechanics.

See also

- Antihydrogen

- Atomic orbital

- Balmer series

- Helium atom

- Hydrogen molecular ion

- List of quantum-mechanical systems with analytical solutions

- Lithium atom

- Proton decay

- Quantum chemistry

- Quantum state

- Trihydrogen cation

References

- Palmer, D. (13 September 1997). "Hydrogen in the Universe". NASA. Archived from the original on 29 October 2014. Retrieved 23 February 2017.

- ^ Housecroft, Catherine E.; Sharpe, Alan G. (2005). Inorganic Chemistry (2nd ed.). Pearson Prentice-Hall. p. 237. ISBN 0130-39913-2.

- Olsen, James; McDonald, Kirk (7 March 2005). "Classical Lifetime of a Bohr Atom" (PDF). Joseph Henry Laboratories, Princeton University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 September 2019. Retrieved 11 December 2015.

- "Derivation of Bohr's Equations for the One-electron Atom" (PDF). University of Massachusetts Boston.

- Eite Tiesinga, Peter J. Mohr, David B. Newell, and Barry N. Taylor (2019), "The 2018 CODATA Recommended Values of the Fundamental Physical Constants" (Web Version 8.0). Database developed by J. Baker, M. Douma, and S. Kotochigova. Available at http://physics.nist.gov/constants, National Institute of Standards and Technology, Gaithersburg, MD 20899. Link to R∞, Link to hcR∞

- "Solving Schrödinger's equation for the hydrogen atom :: Atomic Physics :: Rudi Winter's web space". users.aber.ac.uk. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

- Messiah, Albert (1999). Quantum Mechanics. New York: Dover. p. 1136. ISBN 0-486-40924-4.

- LaguerreL. Wolfram Mathematica page

- Griffiths, p. 152

- Condon and Shortley (1963). The Theory of Atomic Spectra. London: Cambridge. p. 441.

- Griffiths, Ch. 4 p. 89

- Bransden, B. H.; Joachain, C. J. (1983). Physics of Atoms and Molecules. Longman. p. Appendix 5. ISBN 0-582-44401-2.

- Sommerfeld, Arnold (1919). Atombau und Spektrallinien [Atomic Structure and Spectral Lines]. Braunschweig: Friedrich Vieweg und Sohn. ISBN 3-87144-484-7. German English

- Atkins, Peter; de Paula, Julio (2006). Physical Chemistry (8th ed.). W. H. Freeman. p. 349. ISBN 0-7167-8759-8.

- Pauli, W (1926). "Über das Wasserstoffspektrum vom Standpunkt der neuen Quantenmechanik". Zeitschrift für Physik. 36 (5): 336–363. Bibcode:1926ZPhy...36..336P. doi:10.1007/BF01450175. S2CID 128132824.

- Kleinert H. (1968). "Group Dynamics of the Hydrogen Atom" (PDF). Lectures in Theoretical Physics, Edited by W.E. Brittin and A.O. Barut, Gordon and Breach, N.Y. 1968: 427–482.

- Duru I.H., Kleinert H. (1979). "Solution of the path integral for the H-atom" (PDF). Physics Letters B. 84 (2): 185–188. Bibcode:1979PhLB...84..185D. doi:10.1016/0370-2693(79)90280-6.

- Duru I.H., Kleinert H. (1982). "Quantum Mechanics of H-Atom from Path Integrals" (PDF). Fortschr. Phys. 30 (2): 401–435. Bibcode:1982ForPh..30..401D. doi:10.1002/prop.19820300802.

Books

- Griffiths, David J. (1995). Introduction to Quantum Mechanics. Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-111892-7. Section 4.2 deals with the hydrogen atom specifically, but all of Chapter 4 is relevant.

- Kleinert, H. (2009). Path Integrals in Quantum Mechanics, Statistics, Polymer Physics, and Financial Markets, 4th edition, Worldscibooks.com, World Scientific, Singapore (also available online physik.fu-berlin.de)

External links

- The Hydrogen Atom and The Periodic Table - The Feynman Lectures on Physics

- Physics of hydrogen atom on Scienceworld

| Lighter: (none, lightest possible) |

Hydrogen atom is an isotope of hydrogen |

Heavier: hydrogen-2 |

| Decay product of: free neutron helium-2 |

Decay chain of hydrogen atom |

Decays to: Stable |

where

where  is the

is the  is the

is the  where

where  and

and  is

is  . He also supposed that the

. He also supposed that the  where

where  is the

is the  is the

is the  is the

is the  is the

is the  , the value

, the value

is called the Rydberg unit of energy. It is related to the

is called the Rydberg unit of energy. It is related to the  of

of

where

where  is the mass of the atomic nucleus. For hydrogen-1, the quantity

is the mass of the atomic nucleus. For hydrogen-1, the quantity  is about 1/1836 (i.e. the electron-to-proton mass ratio). For deuterium and tritium, the ratios are about 1/3670 and 1/5497 respectively. These figures, when added to 1 in the denominator, represent very small corrections in the value of R, and thus only small corrections to all energy levels in corresponding hydrogen isotopes.

is about 1/1836 (i.e. the electron-to-proton mass ratio). For deuterium and tritium, the ratios are about 1/3670 and 1/5497 respectively. These figures, when added to 1 in the denominator, represent very small corrections in the value of R, and thus only small corrections to all energy levels in corresponding hydrogen isotopes.

, where

, where  is the

is the  . It is given by the square of a mathematical function known as the "

. It is given by the square of a mathematical function known as the " wavefunction. It is written as:

wavefunction. It is written as:

, so the total probability

, so the total probability  of the electron being in a shell at a distance

of the electron being in a shell at a distance  is

is

. That is, the Bohr picture of an electron orbiting the nucleus at radius

. That is, the Bohr picture of an electron orbiting the nucleus at radius  is unity. Then we say that the wavefunction is properly normalized.

is unity. Then we say that the wavefunction is properly normalized.

. The second lowest energy states, just above the ground state, are given by the quantum numbers

. The second lowest energy states, just above the ground state, are given by the quantum numbers  ,

,  , and

, and  . These

. These  states all have the same energy and are known as the

states all have the same energy and are known as the  and

and  states. There is one

states. There is one  and there are three

and there are three

, the equation is written as:

, the equation is written as:

,

,  , and

, and  three independent differential functions appears with A and B being the separation constants:

three independent differential functions appears with A and B being the separation constants:

. Electrons in this state are 45% likely to be found within the solid body shown.

. Electrons in this state are 45% likely to be found within the solid body shown. ,

, is the

is the  ,

, is a

is a  , and

, and is a

is a  and order

and order  .

. , or the generalized Laguerre polynomial appearing in the hydrogen wave function is

, or the generalized Laguerre polynomial appearing in the hydrogen wave function is  instead.

instead.

(

( (

( where

where  is the state represented by the wavefunction

is the state represented by the wavefunction  in

in  is the

is the  which, for the bound states, results in

which, for the bound states, results in

where

where  denotes a

denotes a  is in units of

is in units of  .

.

determines the magnitude of the angular momentum. The magnetic quantum number

determines the magnitude of the angular momentum. The magnetic quantum number  determines the projection of the angular momentum on the (arbitrarily chosen)

determines the projection of the angular momentum on the (arbitrarily chosen)  -axis.

-axis.

Coulomb potential enter (leading to

Coulomb potential enter (leading to  , i.e.,

, i.e.,  .

.

obtained for another preferred axis

obtained for another preferred axis  can always be represented as a suitable superposition of the various states of different

can always be represented as a suitable superposition of the various states of different ![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}E_{j\,n}={}&-\mu c^{2}\left^{2}\right)^{-1/2}\right]\\\approx {}&-{\frac {\mu c^{2}\alpha ^{2}}{2n^{2}}}\left,\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/9e54f0064eafaeab9e7d8b3e5e41e667a3138a7b) where

where  is the

is the  , depending on the orientation of the electron spin relative to the orbital angular momentum. This formula represents a small correction to the energy obtained by Bohr and Schrödinger as given above. The factor in square brackets in the last expression is nearly one; the extra term arises from relativistic effects (for details, see

, depending on the orientation of the electron spin relative to the orbital angular momentum. This formula represents a small correction to the energy obtained by Bohr and Schrödinger as given above. The factor in square brackets in the last expression is nearly one; the extra term arises from relativistic effects (for details, see  axis (in the xy plane). (The figure above does not show these nodes since it plots cross-sections through the xz-plane.)

axis (in the xy plane). (The figure above does not show these nodes since it plots cross-sections through the xz-plane.) (the remaining angular nodes) occur on the

(the remaining angular nodes) occur on the  (vertical) axis.

(vertical) axis. , so in case of a superposition of multiple orbitals, they would oscillate due to the difference in frequency. For example two states, ψ1and ψ2: The wavefunction is given by

, so in case of a superposition of multiple orbitals, they would oscillate due to the difference in frequency. For example two states, ψ1and ψ2: The wavefunction is given by  and the probability function is

and the probability function is