| "I'm My Own Grandpa" | |

|---|---|

| Song by Lonzo and Oscar | |

| Language | English |

| Released | 1947 |

| Genre | Novelty |

| Songwriter(s) | Dwight Latham and Moe Jaffe |

"I'm My Own Grandpa" (sometimes rendered as "I'm My Own Grandpaw") is a novelty song written by Dwight Latham and Moe Jaffe, performed by Lonzo and Oscar in 1947, about a man who, through an unlikely (but legal) combination of marriages, becomes stepfather to his own stepmother. By dropping the "step-" modifiers, he becomes his own grandfather.

In the 1930s, Latham had a group, the Jesters, on network radio; their specialties were bits of spoken humor and novelty songs. While reading a book of Mark Twain anecdotes, he once found a paragraph in which Twain proved it would be possible for a man to become his own grandfather. ("Very Closely Related" appears on page 87 of Wit and Humor of the Age, which was co-authored by Mark Twain in 1883.) In 1947, Latham and Jaffe expanded the idea into a song, which became a hit for Lonzo and Oscar.

Genealogy

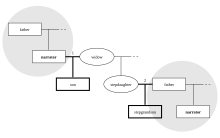

In the song, the narrator marries a widow with an adult daughter. Subsequently, his father marries the widow's daughter. This creates a comic tangle of relationships by a mixture of blood and marriage; for example, the narrator's father is now also his stepson-in-law. The situation is complicated further when both couples have children.

Although the song continues to mention that both the narrator's wife and stepdaughter had children by the narrator and his father, respectively, the narrator actually becomes "his own grandpa" once his father marries the woman's daughter:

- The narrator marries the older woman.

- This results in the woman's daughter becoming his stepdaughter.

- Subsequently, the narrator's father marries the older woman's daughter.

- The woman's daughter, being the new wife of the narrator's father, is now both his stepdaughter and his stepmother. Concurrently, the narrator's father, being his stepdaughter's husband, is also his own stepson-in-law.

- The narrator's wife, being the mother of his stepmother, is both the narrator's spouse and his step-grandmother.

- The husband of the narrator's wife would then be the narrator's step-grandfather. Since the narrator is that person, he has managed to become his own (step-step)grandfather. The "step-step" concept applies because the step-father of one's step-mother would be one's step-step-grandfather, making a "double step" event possible.

- The narrator's wife, being the mother of his stepmother, is both the narrator's spouse and his step-grandmother.

- The woman's daughter, being the new wife of the narrator's father, is now both his stepdaughter and his stepmother. Concurrently, the narrator's father, being his stepdaughter's husband, is also his own stepson-in-law.

The song continues with

- The narrator and his wife having a son.

- The narrator's son is the half-brother of his stepdaughter, as the narrator's wife is the mother of both.

- Since his stepdaughter is also his stepmother, then the narrator's son is also his own (step-half-)uncle because he is the (half-)brother of his (step-)mother.

- The narrator's son is therefore a (half-)brother-in-law to the narrator's father, because the son is the (half-)brother of the father's wife.

- Since his stepdaughter is also his stepmother, then the narrator's son is also his own (step-half-)uncle because he is the (half-)brother of his (step-)mother.

- The narrator's son is the half-brother of his stepdaughter, as the narrator's wife is the mother of both.

- The narrator's father and his wife (the narrator's stepdaughter) then had a son of their own.

- The child is the narrator's (step-) grandson because he is the son of his (step-)daughter.

- The son is the (half-)brother of the narrator because they share a father.

- The child is the narrator's (step-) grandson because he is the son of his (step-)daughter.

Real-life incidents

According to a 2007 article, the song was inspired by an anecdote that has been published periodically by newspapers for well over 150 years. The earliest citation was from the Republican Chronicle of Ithaca, New York on April 24, 1822, and that was copied from the London Literary Gazette:

A proof that a man may be his own Grandfather.—There was a widow and her daughter-in-law, and a man and his son. The widow married the son, and the daughter the old man; the widow was, therefore, mother to her husband's father, consequently grandmother to her own husband. They had a son, to whom she was great-grandmother; now, as the son of a great-grandmother must be either a grandfather or great-uncle, this boy was therefore his own grandfather. N. B. This was actually the case with a boy at a school in Norwich.

An 1884 book, The World of Wonders, attributed the original "remarkable genealogical curiosity" to Hood's Magazine.

In 1989, The Rolling Stones bassist Bill Wyman married Mandy Smith; she was 18 and he 52. In 1993, Wyman's 30-year-old son from his first marriage, Stephen, married Smith's mother, Patsy, who was then aged 46. However this was after Wyman and Smith had divorced.

Cover versions

| This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "I'm My Own Grandpa" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (March 2023) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

The cover version by Lonzo and Oscar was recorded in 1947, the same year that Latham and Jaffe released The Jesters original. A version by Guy Lombardo and The Guy Lombardo Trio became a hit in 1948. The song was also recorded by Phil Harris (as "He's His Own Grandpa"), Jo Stafford (as "I'm My Own Grandmaw"), singer/bandleader Tony Pastor, Kimball Coburn, Homer and Jethro, and "Jon & Alun" (Jon Mark and Alun Davies) on their record Relax Your Mind (1963).

A 1976 episode of The Muppet Show includes a skit in which the song is performed by the all-Muppet Gogolala Jubilee Jugband. Ray Stevens recorded a version for his 1987 album Crackin' Up. In the movie The Stupids, Stanley Stupid, portrayed by Tom Arnold, sings "I'm My Own Grandpa" while on a talk show about strange families. Willie Nelson performed the song on his 2001 album The Rainbow Connection. This song was also performed by Grandpa Jones, who sang it both at the Grand Ole Opry and on the TV show Hee Haw. It was also later recorded on the album Home is Where the Heart Is by David Grisman and on Michael Cooney's album of songs for children. Folk singer Steve Goodman included it in his live shows, and recorded it on his album Somebody Else's Troubles.

The humorous folk singer, Anthony John Clarke, frequently covers it in his gigs and has recorded it on his 2004 album Just Bring Yourself.

In 1984, Norwegian folk singer Øystein Sunde published a Norwegian-language version, «Jeg er min egen bestefar».

Logic and reasoning

See also: Causal loopProfessor Philip Johnson-Laird used the song to illustrate issues in formal logic as contrasted with psychology of reasoning, noting that the transitive property of identity relationships expressed in natural language was highly sensitive to variations in grammar, while reasoning by models, such as the one constructed in the song, avoided this sensitivity.

The situation is included in a set of problems attributed to Alcuin of York, and also in the final story in Baital Pachisi; the question asks to describe the relationship of the children to each other. Alcuin's solution is that the children are simultaneously uncle and nephew to each other; he does not draw attention to the relationships of the other characters.

References

- Wit and Humor of the Age. Star Publishing Company. 1883. p. 87.

- James Plant (August 27, 2007). ""I'm My Own Grandpa" – Where Did the Tale Begin?". GenealogyMagazine.com. Retrieved 2013-05-27.

- Christopher Dunham (September 22, 2006). "Someone Really Was His Own Grandpa". The Genealogue. Retrieved 2013-05-27.

- The World of Wonders. Cassell and Company. 1884. p. 6.

- "The Quiet One review – controversial and evasive Bill Wyman documentary". The Guardian. 3 May 2019. Retrieved 19 January 2021.

- "Bill Wyman and Mandy Smith: Inside the controversial marriage between the Rolling Stones bassist and his teenage bride". Smooth Radio. Global Media & Entertainment. 24 February 2021. Retrieved 9 August 2024.

- RCA 47-7592

- Philip Johnson-Laird (2006). How We Reason. Oxford University Press. pp. 119–135. ISBN 9780198569763.

External links

- DeadDisc list of cover versions

- I'm My Own Grandpaw Lyrics with Java illustration

- Public domain recording by the Jesters at Internet Archive.