In mathematics, an identity is an equality relating one mathematical expression A to another mathematical expression B, such that A and B (which might contain some variables) produce the same value for all values of the variables within a certain domain of discourse. In other words, A = B is an identity if A and B define the same functions, and an identity is an equality between functions that are differently defined. For example, and are identities. Identities are sometimes indicated by the triple bar symbol ≡ instead of =, the equals sign. Formally, an identity is a universally quantified equality.

Common identities

Algebraic identities

See also: Factorization § Recognizable patternsCertain identities, such as and , form the basis of algebra, while other identities, such as and , can be useful in simplifying algebraic expressions and expanding them.

Trigonometric identities

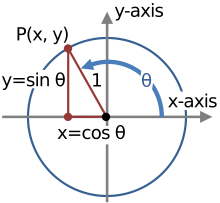

Main article: List of trigonometric identitiesGeometrically, trigonometric identities are identities involving certain functions of one or more angles. They are distinct from triangle identities, which are identities involving both angles and side lengths of a triangle. Only the former are covered in this article.

These identities are useful whenever expressions involving trigonometric functions need to be simplified. Another important application is the integration of non-trigonometric functions: a common technique which involves first using the substitution rule with a trigonometric function, and then simplifying the resulting integral with a trigonometric identity.

One of the most prominent examples of trigonometric identities involves the equation which is true for all real values of . On the other hand, the equation

is only true for certain values of , not all. For example, this equation is true when but false when .

Another group of trigonometric identities concerns the so-called addition/subtraction formulas (e.g. the double-angle identity , the addition formula for ), which can be used to break down expressions of larger angles into those with smaller constituents.

Exponential identities

Main article: ExponentiationThe following identities hold for all integer exponents, provided that the base is non-zero:

Unlike addition and multiplication, exponentiation is not commutative. For example, 2 + 3 = 3 + 2 = 5 and 2 · 3 = 3 · 2 = 6, but 2 = 8 whereas 3 = 9.

Also unlike addition and multiplication, exponentiation is not associative either. For example, (2 + 3) + 4 = 2 + (3 + 4) = 9 and (2 · 3) · 4 = 2 · (3 · 4) = 24, but 2 to the 4 is 8 (or 4,096) whereas 2 to the 3 is 2 (or 2,417,851,639,229,258,349,412,352). When no parentheses are written, by convention the order is top-down, not bottom-up:

- whereas

Logarithmic identities

Main article: Logarithmic identitiesSeveral important formulas, sometimes called logarithmic identities or log laws, relate logarithms to one another:

Product, quotient, power and root

The logarithm of a product is the sum of the logarithms of the numbers being multiplied; the logarithm of the ratio of two numbers is the difference of the logarithms. The logarithm of the pth power of a number is p times the logarithm of the number itself; the logarithm of a pth root is the logarithm of the number divided by p. The following table lists these identities with examples. Each of the identities can be derived after substitution of the logarithm definitions and/or in the left hand sides.

| Formula | Example | |

|---|---|---|

| product | ||

| quotient | ||

| power | ||

| root |

Change of base

The logarithm logb(x) can be computed from the logarithms of x and b with respect to an arbitrary base k using the following formula:

Typical scientific calculators calculate the logarithms to bases 10 and e. Logarithms with respect to any base b can be determined using either of these two logarithms by the previous formula:

Given a number x and its logarithm logb(x) to an unknown base b, the base is given by:

Hyperbolic function identities

Main article: Hyperbolic functionThe hyperbolic functions satisfy many identities, all of them similar in form to the trigonometric identities. In fact, Osborn's rule states that one can convert any trigonometric identity into a hyperbolic identity by expanding it completely in terms of integer powers of sines and cosines, changing sine to sinh and cosine to cosh, and switching the sign of every term which contains a product of an even number of hyperbolic sines.

The Gudermannian function gives a direct relationship between the trigonometric functions and the hyperbolic ones that does not involve complex numbers.

Logic and universal algebra

Formally, an identity is a true universally quantified formula of the form where s and t are terms with no other free variables than The quantifier prefix is often left implicit, when it is stated that the formula is an identity. For example, the axioms of a monoid are often given as the formulas

or, shortly,

So, these formulas are identities in every monoid. As for any equality, the formulas without quantifier are often called equations. In other words, an identity is an equation that is true for all values of the variables.

See also

References

Notes

- All statements in this section can be found in Shirali 2002, Section 4, Downing 2003, p. 275, or Kate & Bhapkar 2009, p. 1-1, for example.

Citations

- Equation. Encyclopedia of Mathematics. URL: http://encyclopediaofmath.org/index.php?title=Equation&oldid=32613

- Pratt, Vaughan, "Algebra", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2022 Edition), Edward N. Zalta & Uri Nodelman (eds.), URL: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/algebra/#Laws

- "Mathwords: Identity". www.mathwords.com. Retrieved 2019-12-01.

- "Identity – math word definition – Math Open Reference". www.mathopenref.com. Retrieved 2019-12-01.

- "Basic Identities". www.math.com. Retrieved 2019-12-01.

- "Algebraic Identities". www.sosmath.com. Retrieved 2019-12-01.

- Stapel, Elizabeth. "Trigonometric Identities". Purplemath. Retrieved 2019-12-01.

- Bernstein, Stephen; Bernstein, Ruth (1999), Schaum's outline of theory and problems of elements of statistics. I, Descriptive statistics and probability, Schaum's outline series, New York: McGraw-Hill, ISBN 978-0-07-005023-5, p. 21

- Osborn, G. (1 January 1902). "109. Mnemonic for Hyperbolic Formulae". The Mathematical Gazette. 2 (34): 189. doi:10.2307/3602492. JSTOR 3602492.

- Peterson, John Charles (2003). Technical mathematics with calculus (3rd ed.). Cengage Learning. p. 1155. ISBN 0-7668-6189-9., Chapter 26, page 1155

- Nachum Dershowitz; Jean-Pierre Jouannaud (1990). "Rewrite Systems". In Jan van Leeuwen (ed.). Formal Models and Semantics. Handbook of Theoretical Computer Science. Vol. B. Elsevier. pp. 243–320.

- Wolfgang Wechsler (1992). Wilfried Brauer; Grzegorz Rozenberg; Arto Salomaa (eds.). Universal Algebra for Computer Scientists. EATCS Monographs on Theoretical Computer Science. Vol. 25. Berlin: Springer. ISBN 3-540-54280-9. Here: Def.1 of Sect.3.2.1, p.160.

Sources

- Downing, Douglas (2003). Algebra the Easy Way. Barrons Educational Series. ISBN 978-0-7641-1972-9.

- Kate, S.K.; Bhapkar, H.R. (2009). Basics Of Mathematics. Technical Publications. ISBN 978-81-8431-755-8.

- Shirali, S. (2002). Adventures in Problem Solving. Universities Press. ISBN 978-81-7371-413-9.

External links

- The Encyclopedia of Equation Online encyclopedia of mathematical identities (archived)

- A Collection of Algebraic Identities Archived 2011-10-01 at the Wayback Machine

, the point

, the point  lies on the

lies on the  . Thus,

. Thus,  .

. and

and  and

and  , form the basis of

, form the basis of  , can be useful in simplifying algebraic expressions and expanding them.

, can be useful in simplifying algebraic expressions and expanding them.

which is true for all

which is true for all

but false when

but false when  .

.

, the addition formula for

, the addition formula for  ), which can be used to break down expressions of larger angles into those with smaller constituents.

), which can be used to break down expressions of larger angles into those with smaller constituents.

whereas

whereas

and/or

and/or  in the left hand sides.

in the left hand sides.

where s and t are

where s and t are  The quantifier prefix

The quantifier prefix  is often left implicit, when it is stated that the formula is an identity. For example, the

is often left implicit, when it is stated that the formula is an identity. For example, the