| Radiation therapy | |

|---|---|

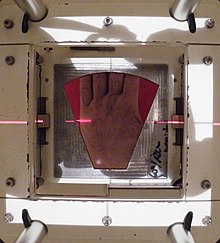

Radiation therapy of the pelvis, using a Varian Clinac iX linear accelerator. Lasers and a mould under the legs are used to determine exact position. Radiation therapy of the pelvis, using a Varian Clinac iX linear accelerator. Lasers and a mould under the legs are used to determine exact position. | |

| ICD-10-PCS | D |

| ICD-9-CM | 92.2-92.3 |

| MeSH | D011878 |

| OPS-301 code | 8–52 |

| MedlinePlus | 001918 |

| [edit on Wikidata] | |

Radiation therapy or radiotherapy (RT, RTx, or XRT) is a treatment using ionizing radiation, generally provided as part of cancer therapy to either kill or control the growth of malignant cells. It is normally delivered by a linear particle accelerator. Radiation therapy may be curative in a number of types of cancer if they are localized to one area of the body, and have not spread to other parts. It may also be used as part of adjuvant therapy, to prevent tumor recurrence after surgery to remove a primary malignant tumor (for example, early stages of breast cancer). Radiation therapy is synergistic with chemotherapy, and has been used before, during, and after chemotherapy in susceptible cancers. The subspecialty of oncology concerned with radiotherapy is called radiation oncology. A physician who practices in this subspecialty is a radiation oncologist.

Radiation therapy is commonly applied to the cancerous tumor because of its ability to control cell growth. Ionizing radiation works by damaging the DNA of cancerous tissue leading to cellular death. To spare normal tissues (such as skin or organs which radiation must pass through to treat the tumor), shaped radiation beams are aimed from several angles of exposure to intersect at the tumor, providing a much larger absorbed dose there than in the surrounding healthy tissue. Besides the tumor itself, the radiation fields may also include the draining lymph nodes if they are clinically or radiologically involved with the tumor, or if there is thought to be a risk of subclinical malignant spread. It is necessary to include a margin of normal tissue around the tumor to allow for uncertainties in daily set-up and internal tumor motion. These uncertainties can be caused by internal movement (for example, respiration and bladder filling) and movement of external skin marks relative to the tumor position.

Radiation oncology is the medical specialty concerned with prescribing radiation, and is distinct from radiology, the use of radiation in medical imaging and diagnosis. Radiation may be prescribed by a radiation oncologist with intent to cure or for adjuvant therapy. It may also be used as palliative treatment (where cure is not possible and the aim is for local disease control or symptomatic relief) or as therapeutic treatment (where the therapy has survival benefit and can be curative). It is also common to combine radiation therapy with surgery, chemotherapy, hormone therapy, immunotherapy or some mixture of the four. Most common cancer types can be treated with radiation therapy in some way.

The precise treatment intent (curative, adjuvant, neoadjuvant therapeutic, or palliative) will depend on the tumor type, location, and stage, as well as the general health of the patient. Total body irradiation (TBI) is a radiation therapy technique used to prepare the body to receive a bone marrow transplant. Brachytherapy, in which a radioactive source is placed inside or next to the area requiring treatment, is another form of radiation therapy that minimizes exposure to healthy tissue during procedures to treat cancers of the breast, prostate, and other organs. Radiation therapy has several applications in non-malignant conditions, such as the treatment of trigeminal neuralgia, acoustic neuromas, severe thyroid eye disease, pterygium, pigmented villonodular synovitis, and prevention of keloid scar growth, vascular restenosis, and heterotopic ossification. The use of radiation therapy in non-malignant conditions is limited partly by worries about the risk of radiation-induced cancers.

Medical uses

It is estimated that half of the US' 1.2M invasive cancer cases diagnosed in 2022 received radiation therapy in their treatment program. Different cancers respond to radiation therapy in different ways.

The response of a cancer to radiation is described by its radiosensitivity. Highly radiosensitive cancer cells are rapidly killed by modest doses of radiation. These include leukemias, most lymphomas, and germ cell tumors. The majority of epithelial cancers are only moderately radiosensitive, and require a significantly higher dose of radiation (60–70 Gy) to achieve a radical cure. Some types of cancer are notably radioresistant, that is, much higher doses are required to produce a radical cure than may be safe in clinical practice. Renal cell cancer and melanoma are generally considered to be radioresistant but radiation therapy is still a palliative option for many patients with metastatic melanoma. Combining radiation therapy with immunotherapy is an active area of investigation and has shown some promise for melanoma and other cancers.

It is important to distinguish the radiosensitivity of a particular tumor, which to some extent is a laboratory measure, from the radiation "curability" of a cancer in actual clinical practice. For example, leukemias are not generally curable with radiation therapy, because they are disseminated through the body. Lymphoma may be radically curable if it is localized to one area of the body. Similarly, many of the common, moderately radioresponsive tumors are routinely treated with curative doses of radiation therapy if they are at an early stage. For example, non-melanoma skin cancer, head and neck cancer, breast cancer, non-small cell lung cancer, cervical cancer, anal cancer, and prostate cancer. With the exception of oligometastatic disease, metastatic cancers are incurable with radiation therapy because it is not possible to treat the whole body.

Modern radiation therapy relies on a CT scan to identify the tumor and surrounding normal structures and to perform dose calculations for the creation of a complex radiation treatment plan. The patient receives small skin marks to guide the placement of treatment fields. Patient positioning is crucial at this stage as the patient will have to be placed in an identical position during each treatment. Many patient positioning devices have been developed for this purpose, including masks and cushions which can be molded to the patient. Image-guided radiation therapy is a method that uses imaging to correct for positional errors of each treatment session.

The response of a tumor to radiation therapy is also related to its size. Due to complex radiobiology, very large tumors are affected less by radiation compared to smaller tumors or microscopic disease. Various strategies are used to overcome this effect. The most common technique is surgical resection prior to radiation therapy. This is most commonly seen in the treatment of breast cancer with wide local excision or mastectomy followed by adjuvant radiation therapy. Another method is to shrink the tumor with neoadjuvant chemotherapy prior to radical radiation therapy. A third technique is to enhance the radiosensitivity of the cancer by giving certain drugs during a course of radiation therapy. Examples of radiosensitizing drugs include cisplatin, nimorazole, and cetuximab.

The impact of radiotherapy varies between different types of cancer and different groups. For example, for breast cancer after breast-conserving surgery, radiotherapy has been found to halve the rate at which the disease recurs. In pancreatic cancer, radiotherapy has increased survival times for inoperable tumors.

Side effects

Radiation therapy (RT) is in itself painless, but has iatrogenic side effect risks. Many low-dose palliative treatments (for example, radiation therapy to bony metastases) cause minimal or no side effects, although short-term pain flare-up can be experienced in the days following treatment due to oedema compressing nerves in the treated area. Higher doses can cause varying side effects during treatment (acute side effects), in the months or years following treatment (long-term side effects), or after re-treatment (cumulative side effects). The nature, severity, and longevity of side effects depends on the organs that receive the radiation, the treatment itself (type of radiation, dose, fractionation, concurrent chemotherapy), and the patient. Serious radiation complications may occur in 5% of RT cases. Acute (near immediate) or sub-acute (2 to 3 months post RT) radiation side effects may develop after 50 Gy RT dosing. Late or delayed radiation injury (6 months to decades) may develop after 65 Gy.

Most side effects are predictable and expected. Side effects from radiation are usually limited to the area of the patient's body that is under treatment. Side effects are dose-dependent; for example, higher doses of head and neck radiation can be associated with cardiovascular complications, thyroid dysfunction, and pituitary axis dysfunction. Modern radiation therapy aims to reduce side effects to a minimum and to help the patient understand and deal with side effects that are unavoidable.

The main side effects reported are fatigue and skin irritation, like a mild to moderate sun burn. The fatigue often sets in during the middle of a course of treatment and can last for weeks after treatment ends. The irritated skin will heal, but may not be as elastic as it was before.

Acute side effects

- Nausea and vomiting

- This is not a general side effect of radiation therapy, and mechanistically is associated only with treatment of the stomach or abdomen (which commonly react a few hours after treatment), or with radiation therapy to certain nausea-producing structures in the head during treatment of certain head and neck tumors, most commonly the vestibules of the inner ears. As with any distressing treatment, some patients vomit immediately during radiotherapy, or even in anticipation of it, but this is considered a psychological response. Nausea for any reason can be treated with antiemetics.

- Damage to the epithelial surfaces

- Epithelial surfaces may sustain damage from radiation therapy. Depending on the area being treated, this may include the skin, oral mucosa, pharyngeal, bowel mucosa, and ureter. The rates of onset of damage and recovery from it depend upon the turnover rate of epithelial cells. Typically the skin starts to become pink and sore several weeks into treatment. The reaction may become more severe during the treatment and for up to about one week following the end of radiation therapy, and the skin may break down. Although this moist desquamation is uncomfortable, recovery is usually quick. Skin reactions tend to be worse in areas where there are natural folds in the skin, such as underneath the female breast, behind the ear, and in the groin.

- Mouth, throat and stomach sores

- If the head and neck area is treated, temporary soreness and ulceration commonly occur in the mouth and throat. If severe, this can affect swallowing, and the patient may need painkillers and nutritional support/food supplements. The esophagus can also become sore if it is treated directly, or if, as commonly occurs, it receives a dose of collateral radiation during treatment of lung cancer. When treating liver malignancies and metastases, it is possible for collateral radiation to cause gastric, stomach, or duodenal ulcers This collateral radiation is commonly caused by non-targeted delivery (reflux) of the radioactive agents being infused. Methods, techniques and devices are available to lower the occurrence of this type of adverse side effect.

- Intestinal discomfort

- The lower bowel may be treated directly with radiation (treatment of rectal or anal cancer) or be exposed by radiation therapy to other pelvic structures (prostate, bladder, female genital tract). Typical symptoms are soreness, diarrhoea, and nausea. Nutritional interventions may be able to help with diarrhoea associated with radiotherapy. Studies in people having pelvic radiotherapy as part of anticancer treatment for a primary pelvic cancer found that changes in dietary fat, fibre and lactose during radiotherapy reduced diarrhoea at the end of treatment.

- Swelling

- As part of the general inflammation that occurs, swelling of soft tissues may cause problems during radiation therapy. This is a concern during treatment of brain tumors and brain metastases, especially where there is pre-existing raised intracranial pressure or where the tumor is causing near-total obstruction of a lumen (e.g., trachea or main bronchus). Surgical intervention may be considered prior to treatment with radiation. If surgery is deemed unnecessary or inappropriate, the patient may receive steroids during radiation therapy to reduce swelling.

- Infertility

- The gonads (ovaries and testicles) are very sensitive to radiation. They may be unable to produce gametes following direct exposure to most normal treatment doses of radiation. Treatment planning for all body sites is designed to minimize, if not completely exclude dose to the gonads if they are not the primary area of treatment.

Late side effects

Late side effects occur months to years after treatment and are generally limited to the area that has been treated. They are often due to damage of blood vessels and connective tissue cells. Many late effects are reduced by fractionating treatment into smaller parts.

- Fibrosis

- Tissues which have been irradiated tend to become less elastic over time due to a diffuse scarring process.

- Epilation

- Epilation (hair loss) may occur on any hair bearing skin with doses above 1 Gy. It only occurs within the radiation field/s. Hair loss may be permanent with a single dose of 10 Gy, but if the dose is fractionated permanent hair loss may not occur until dose exceeds 45 Gy.

- Dryness

- The salivary glands and tear glands have a radiation tolerance of about 30 Gy in 2 Gy fractions, a dose which is exceeded by most radical head and neck cancer treatments. Dry mouth (xerostomia) and dry eyes (xerophthalmia) can become irritating long-term problems and severely reduce the patient's quality of life. Similarly, sweat glands in treated skin (such as the armpit) tend to stop working, and the naturally moist vaginal mucosa is often dry following pelvic irradiation.

- Chronic sinus drainage

- Radiation therapy treatments to the head and neck regions for soft tissue, palate or bone cancer can cause chronic sinus tract draining and fistulae from the bone.

- Lymphedema

- Lymphedema, a condition of localized fluid retention and tissue swelling, can result from damage to the lymphatic system sustained during radiation therapy. It is the most commonly reported complication in breast radiation therapy patients who receive adjuvant axillary radiotherapy following surgery to clear the axillary lymph nodes .

- Cancer

- Radiation is a potential cause of cancer, and secondary malignancies are seen in some patients. Cancer survivors are already more likely than the general population to develop malignancies due to a number of factors including lifestyle choices, genetics, and previous radiation treatment. It is difficult to directly quantify the rates of these secondary cancers from any single cause. Studies have found radiation therapy as the cause of secondary malignancies for only a small minority of patients. New techniques such as proton beam therapy and carbon ion radiotherapy which aim to reduce dose to healthy tissues will lower these risks. It starts to occur 4–6 years following treatment, although some haematological malignancies may develop within 3 years. In the vast majority of cases, this risk is greatly outweighed by the reduction in risk conferred by treating the primary cancer even in pediatric malignancies which carry a higher burden of secondary malignancies.

- Cardiovascular disease

- Radiation can increase the risk of heart disease and death as observed in previous breast cancer RT regimens. Therapeutic radiation increases the risk of a subsequent cardiovascular event (i.e., heart attack or stroke) by 1.5 to 4 times a person's normal rate, aggravating factors included. The increase is dose dependent, related to the RT's dose strength, volume and location. Use of concomitant chemotherapy, e.g. anthracyclines, is an aggravating risk factor. The occurrence rate of RT induced cardiovascular disease is estimated between 10 and 30%.

- Cardiovascular late side effects have been termed radiation-induced heart disease (RIHD) and radiation-induced cardiovascular disease (RIVD). Symptoms are dose dependent and include cardiomyopathy, myocardial fibrosis, valvular heart disease, coronary artery disease, heart arrhythmia and peripheral artery disease. Radiation-induced fibrosis, vascular cell damage and oxidative stress can lead to these and other late side effect symptoms. Most radiation-induced cardiovascular diseases occur 10 or more years post treatment, making causality determinations more difficult.

- Cognitive decline

- In cases of radiation applied to the head radiation therapy may cause cognitive decline. Cognitive decline was especially apparent in young children, between the ages of 5 and 11. Studies found, for example, that the IQ of 5-year-old children declined each year after treatment by several IQ points.

- Radiation enteropathy

- The gastrointestinal tract can be damaged following abdominal and pelvic radiotherapy. Atrophy, fibrosis and vascular changes produce malabsorption, diarrhea, steatorrhea and bleeding with bile acid diarrhea and vitamin B12 malabsorption commonly found due to ileal involvement. Pelvic radiation disease includes radiation proctitis, producing bleeding, diarrhoea and urgency, and can also cause radiation cystitis when the bladder is affected.

- Lung injury

- Radiation-induced lung injury (RILI) encompasses radiation pneumonitis and pulmonary fibrosis. Lung tissue is sensitive to ionizing radiation, tolerating only 18–20 Gy, a fraction of typical therapeutic dosage levels. The lung's terminal airways and associated alveoli can become damaged, preventing effective respiratory gas exchange. The adverse effects of radiation are often asymptomatic with clinically significant RILI occurrence rates varying widely in literature, affecting 5–25% of those treated for thoracic and mediastinal malignancies and 1–5% of those treated for breast cancer.

- Radiation-induced polyneuropathy

- Radiation treatments may damage nerves near the target area or within the delivery path as nerve tissue is also radiosensitive. Nerve damage from ionizing radiation occurs in phases, the initial phase from microvascular injury, capillary damage and nerve demyelination. Subsequent damage occurs from vascular constriction and nerve compression due to uncontrolled fibrous tissue growth caused by radiation. Radiation-induced polyneuropathy, ICD-10-CM Code G62.82, occurs in approximately 1–5% of those receiving radiation therapy.

- Depending upon the irradiated zone, late effect neuropathy may occur in either the central nervous system (CNS) or the peripheral nervous system (PNS). In the CNS for example, cranial nerve injury typically presents as a visual acuity loss 1–14 years post treatment. In the PNS, injury to the plexus nerves presents as radiation-induced brachial plexopathy or radiation-induced lumbosacral plexopathy appearing up to 3 decades post treatment.

- Myokymia (muscle cramping, spasms or twitching) may develop. Radiation-induced nerve injury, chronic compressive neuropathies and polyradiculopathies are the most common cause of myokymic discharges. Clinically, the majority of patients receiving radiation therapy have measurable myokymic discharges within their field of radiation which present as focal or segmental myokymia. Common areas affected include the arms, legs or face depending upon the location of nerve injury. Myokymia is more frequent when radiation doses exceed 10 gray (Gy).

- Radiation necrosis

- Radiation necrosis is the death of healthy tissue near the irradiated site. It is a type of coagulative necrosis that occurs because the radiation directly or indirectly damages blood vessels in the area, which reduces the blood supply to the remaining healthy tissue, causing it to die by ischemia, similar to what happens in an ischemic stroke. Because it is an indirect effect of the treatment, it occurs months to decades after radiation exposure. Radiation necrosis most commonly presents as osteoradionecrosis, vaginal radionecrosis, soft tissue radionecrosis, or laryngeal radionecrosis.

Cumulative side effects

Cumulative effects from this process should not be confused with long-term effects – when short-term effects have disappeared and long-term effects are subclinical, reirradiation can still be problematic. These doses are calculated by the radiation oncologist and many factors are taken into account before the subsequent radiation takes place.

Effects on reproduction

During the first two weeks after fertilization, radiation therapy is lethal but not teratogenic. High doses of radiation during pregnancy induce anomalies, impaired growth and intellectual disability, and there may be an increased risk of childhood leukemia and other tumors in the offspring.

In males previously having undergone radiotherapy, there appears to be no increase in genetic defects or congenital malformations in their children conceived after therapy. However, the use of assisted reproductive technologies and micromanipulation techniques might increase this risk.

Effects on pituitary system

Hypopituitarism commonly develops after radiation therapy for sellar and parasellar neoplasms, extrasellar brain tumors, head and neck tumors, and following whole body irradiation for systemic malignancies. 40–50% of children treated for childhood cancer develop some endocrine side effect. Radiation-induced hypopituitarism mainly affects growth hormone and gonadal hormones. In contrast, adrenocorticotrophic hormone (ACTH) and thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) deficiencies are the least common among people with radiation-induced hypopituitarism. Changes in prolactin-secretion is usually mild, and vasopressin deficiency appears to be very rare as a consequence of radiation.

Effects on subsequent surgery

Delayed tissue injury with impaired wound healing capability often develops after receiving doses in excess of 65 Gy. A diffuse injury pattern due to the external beam radiotherapy's holographic isodosing occurs. While the targeted tumor receives the majority of radiation, healthy tissue at incremental distances from the center of the tumor are also irradiated in a diffuse pattern due to beam divergence. These wounds demonstrate progressive, proliferative endarteritis, inflamed arterial linings that disrupt the tissue's blood supply. Such tissue ends up chronically hypoxic, fibrotic, and without an adequate nutrient and oxygen supply. Surgery of previously irradiated tissue has a very high failure rate, e.g. women who have received radiation for breast cancer develop late effect chest wall tissue fibrosis and hypovascularity, making successful reconstruction and healing difficult, if not impossible.

Radiation therapy accidents

There are rigorous procedures in place to minimise the risk of accidental overexposure of radiation therapy to patients. However, mistakes do occasionally occur; for example, the radiation therapy machine Therac-25 was responsible for at least six accidents between 1985 and 1987, where patients were given up to one hundred times the intended dose; two people were killed directly by the radiation overdoses. From 2005 to 2010, a hospital in Missouri overexposed 76 patients (most with brain cancer) during a five-year period because new radiation equipment had been set up incorrectly.

Although medical errors are exceptionally rare, radiation oncologists, medical physicists and other members of the radiation therapy treatment team are working to eliminate them. In 2010 the American Society for Radiation Oncology (ASTRO) launched a safety initiative called Target Safely that, among other things, aimed to record errors nationwide so that doctors can learn from each and every mistake and prevent them from recurring. ASTRO also publishes a list of questions for patients to ask their doctors about radiation safety to ensure every treatment is as safe as possible.

Use in non-cancerous diseases

Radiation therapy is used to treat early stage Dupuytren's disease and Ledderhose disease. When Dupuytren's disease is at the nodules and cords stage or fingers are at a minimal deformation stage of less than 10 degrees, then radiation therapy is used to prevent further progress of the disease. Radiation therapy is also used post surgery in some cases to prevent the disease continuing to progress. Low doses of radiation are used typically three gray of radiation for five days, with a break of three months followed by another phase of three gray of radiation for five days.

Technique

Mechanism of action

Radiation therapy works by damaging the DNA of cancer cells and can cause them to undergo mitotic catastrophe. This DNA damage is caused by one of two types of energy, photon or charged particle. This damage is either direct or indirect ionization of the atoms which make up the DNA chain. Indirect ionization happens as a result of the ionization of water, forming free radicals, notably hydroxyl radicals, which then damage the DNA.

In photon therapy, most of the radiation effect is through free radicals. Cells have mechanisms for repairing single-strand DNA damage and double-stranded DNA damage. However, double-stranded DNA breaks are much more difficult to repair, and can lead to dramatic chromosomal abnormalities and genetic deletions. Targeting double-stranded breaks increases the probability that cells will undergo cell death. Cancer cells are generally less differentiated and more stem cell-like; they reproduce more than most healthy differentiated cells, and have a diminished ability to repair sub-lethal damage. Single-strand DNA damage is then passed on through cell division; damage to the cancer cells' DNA accumulates, causing them to die or reproduce more slowly.

One of the major limitations of photon radiation therapy is that the cells of solid tumors become deficient in oxygen. Solid tumors can outgrow their blood supply, causing a low-oxygen state known as hypoxia. Oxygen is a potent radiosensitizer, increasing the effectiveness of a given dose of radiation by forming DNA-damaging free radicals. Tumor cells in a hypoxic environment may be as much as 2 to 3 times more resistant to radiation damage than those in a normal oxygen environment. Much research has been devoted to overcoming hypoxia including the use of high pressure oxygen tanks, hyperthermia therapy (heat therapy which dilates blood vessels to the tumor site), blood substitutes that carry increased oxygen, hypoxic cell radiosensitizer drugs such as misonidazole and metronidazole, and hypoxic cytotoxins (tissue poisons), such as tirapazamine. Newer research approaches are currently being studied, including preclinical and clinical investigations into the use of an oxygen diffusion-enhancing compound such as trans sodium crocetinate as a radiosensitizer.

Charged particles such as protons and boron, carbon, and neon ions can cause direct damage to cancer cell DNA through high-LET (linear energy transfer) and have an antitumor effect independent of tumor oxygen supply because these particles act mostly via direct energy transfer usually causing double-stranded DNA breaks. Due to their relatively large mass, protons and other charged particles have little lateral side scatter in the tissue – the beam does not broaden much, stays focused on the tumor shape, and delivers small dose side-effects to surrounding tissue. They also more precisely target the tumor using the Bragg peak effect. See proton therapy for a good example of the different effects of intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) vs. charged particle therapy. This procedure reduces damage to healthy tissue between the charged particle radiation source and the tumor and sets a finite range for tissue damage after the tumor has been reached. In contrast, IMRT's use of uncharged particles causes its energy to damage healthy cells when it exits the body. This exiting damage is not therapeutic, can increase treatment side effects, and increases the probability of secondary cancer induction. This difference is very important in cases where the close proximity of other organs makes any stray ionization very damaging (example: head and neck cancers). This X-ray exposure is especially bad for children, due to their growing bodies, and while depending on a multitude of factors, they are around 10 times more sensitive to developing secondary malignancies after radiotherapy as compared to adults.

Dose

The amount of radiation used in photon radiation therapy is measured in grays (Gy), and varies depending on the type and stage of cancer being treated. For curative cases, the typical dose for a solid epithelial tumor ranges from 60 to 80 Gy, while lymphomas are treated with 20 to 40 Gy.

Preventive (adjuvant) doses are typically around 45–60 Gy in 1.8–2 Gy fractions (for breast, head, and neck cancers.) Many other factors are considered by radiation oncologists when selecting a dose, including whether the patient is receiving chemotherapy, patient comorbidities, whether radiation therapy is being administered before or after surgery, and the degree of success of surgery.

Delivery parameters of a prescribed dose are determined during treatment planning (part of dosimetry). Treatment planning is generally performed on dedicated computers using specialized treatment planning software. Depending on the radiation delivery method, several angles or sources may be used to sum to the total necessary dose. The planner will try to design a plan that delivers a uniform prescription dose to the tumor and minimizes dose to surrounding healthy tissues.

In radiation therapy, three-dimensional dose distributions may be evaluated using the dosimetry technique known as gel dosimetry.

Fractionation

This section only applies to photon radiotherapy although other types of radiation therapy may be fractionated Main article: Dose fractionationThe total dose is fractionated (spread out over time) for several important reasons. Fractionation allows normal cells time to recover, while tumor cells are generally less efficient in repair between fractions. Fractionation also allows tumor cells that were in a relatively radio-resistant phase of the cell cycle during one treatment to cycle into a sensitive phase of the cycle before the next fraction is given. Similarly, tumor cells that were chronically or acutely hypoxic (and therefore more radioresistant) may reoxygenate between fractions, improving the tumor cell kill.

Fractionation regimens are individualised between different radiation therapy centers and even between individual doctors. In North America, Australia, and Europe, the typical fractionation schedule for adults is 1.8 to 2 Gy per day, five days a week. In some cancer types, prolongation of the fraction schedule over too long can allow for the tumor to begin repopulating, and for these tumor types, including head-and-neck and cervical squamous cell cancers, radiation treatment is preferably completed within a certain amount of time. For children, a typical fraction size may be 1.5 to 1.8 Gy per day, as smaller fraction sizes are associated with reduced incidence and severity of late-onset side effects in normal tissues.

In some cases, two fractions per day are used near the end of a course of treatment. This schedule, known as a concomitant boost regimen or hyperfractionation, is used on tumors that regenerate more quickly when they are smaller. In particular, tumors in the head-and-neck demonstrate this behavior.

Patients receiving palliative radiation to treat uncomplicated painful bone metastasis should not receive more than a single fraction of radiation. A single treatment gives comparable pain relief and morbidity outcomes to multiple-fraction treatments, and for patients with limited life expectancy, a single treatment is best to improve patient comfort.

Schedules for fractionation

One fractionation schedule that is increasingly being used and continues to be studied is hypofractionation. This is a radiation treatment in which the total dose of radiation is divided into large doses. Typical doses vary significantly by cancer type, from 2.2 Gy/fraction to 20 Gy/fraction, the latter being typical of stereotactic treatments (stereotactic ablative body radiotherapy, or SABR – also known as SBRT, or stereotactic body radiotherapy) for subcranial lesions, or SRS (stereotactic radiosurgery) for intracranial lesions. The rationale of hypofractionation is to reduce the probability of local recurrence by denying clonogenic cells the time they require to reproduce and also to exploit the radiosensitivity of some tumors. In particular, stereotactic treatments are intended to destroy clonogenic cells by a process of ablation, i.e., the delivery of a dose intended to destroy clonogenic cells directly, rather than to interrupt the process of clonogenic cell division repeatedly (apoptosis), as in routine radiotherapy.

Estimation of dose based on target sensitivity

Different cancer types have different radiation sensitivity. While predicting the sensitivity based on genomic or proteomic analyses of biopsy samples has proven challenging, the predictions of radiation effect on individual patients from genomic signatures of intrinsic cellular radiosensitivity have been shown to associate with clinical outcome. An alternative approach to genomics and proteomics was offered by the discovery that radiation protection in microbes is offered by non-enzymatic complexes of manganese and small organic metabolites. The content and variation of manganese (measurable by electron paramagnetic resonance) were found to be good predictors of radiosensitivity, and this finding extends also to human cells. An association was confirmed between total cellular manganese contents and their variation, and clinically inferred radioresponsiveness in different tumor cells, a finding that may be useful for more precise radiodosages and improved treatment of cancer patients.

Types

Historically, the three main divisions of radiation therapy are:

- external beam radiation therapy (EBRT or XRT) or teletherapy;

- brachytherapy or sealed source radiation therapy; and

- systemic radioisotope therapy or unsealed source radiotherapy.

The differences relate to the position of the radiation source; external is outside the body, brachytherapy uses sealed radioactive sources placed precisely in the area under treatment, and systemic radioisotopes are given by infusion or oral ingestion. Brachytherapy can use temporary or permanent placement of radioactive sources. The temporary sources are usually placed by a technique called afterloading. In afterloading a hollow tube or applicator is placed surgically in the organ to be treated, and the sources are loaded into the applicator after the applicator is implanted. This minimizes radiation exposure to health care personnel.

Particle therapy is a special case of external beam radiation therapy where the particles are protons or heavier ions.

A review of radiation therapy randomised clinical trials from 2018 to 2021 found many practice-changing data and new concepts that emerge from RCTs, identifying techniques that improve the therapeutic ratio, techniques that lead to more tailored treatments, stressing the importance of patient satisfaction, and identifying areas that require further study.

External beam radiation therapy

Main article: External beam radiation therapyThe following three sections refer to treatment using X-rays.

Conventional external beam radiation therapy

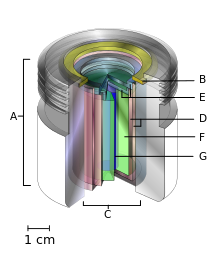

- an international standard source holder (usually lead),

- a retaining ring, and

- a teletherapy "source" composed of

- two nested stainless steel canisters welded to

- two stainless steel lids surrounding

- a protective internal shield (usually uranium metal or a tungsten alloy) and

- a cylinder of radioactive source material, often but not always cobalt-60. The diameter of the "source" is 30 mm.

Historically conventional external beam radiation therapy (2DXRT) was delivered via two-dimensional beams using kilovoltage therapy X-ray units, medical linear accelerators that generate high-energy X-rays, or with machines that were similar to a linear accelerator in appearance, but used a sealed radioactive source like the one shown above. 2DXRT mainly consists of a single beam of radiation delivered to the patient from several directions: often front or back, and both sides.

Conventional refers to the way the treatment is planned or simulated on a specially calibrated diagnostic X-ray machine known as a simulator because it recreates the linear accelerator actions (or sometimes by eye), and to the usually well-established arrangements of the radiation beams to achieve a desired plan. The aim of simulation is to accurately target or localize the volume which is to be treated. This technique is well established and is generally quick and reliable. The worry is that some high-dose treatments may be limited by the radiation toxicity capacity of healthy tissues which lie close to the target tumor volume.

An example of this problem is seen in radiation of the prostate gland, where the sensitivity of the adjacent rectum limited the dose which could be safely prescribed using 2DXRT planning to such an extent that tumor control may not be easily achievable. Prior to the invention of the CT, physicians and physicists had limited knowledge about the true radiation dosage delivered to both cancerous and healthy tissue. For this reason, 3-dimensional conformal radiation therapy has become the standard treatment for almost all tumor sites. More recently other forms of imaging are used including MRI, PET, SPECT and Ultrasound.

Stereotactic radiation

Main article: RadiosurgeryStereotactic radiation is a specialized type of external beam radiation therapy. It uses focused radiation beams targeting a well-defined tumor using extremely detailed imaging scans. Radiation oncologists perform stereotactic treatments, often with the help of a neurosurgeon for tumors in the brain or spine.

There are two types of stereotactic radiation. Stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) is when doctors use a single or several stereotactic radiation treatments of the brain or spine. Stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) refers to one or several stereotactic radiation treatments with the body, such as the lungs.

Some doctors say an advantage to stereotactic treatments is that they deliver the right amount of radiation to the cancer in a shorter amount of time than traditional treatments, which can often take 6 to 11 weeks. Plus treatments are given with extreme accuracy, which should limit the effect of the radiation on healthy tissues. One problem with stereotactic treatments is that they are only suitable for certain small tumors.

Stereotactic treatments can be confusing because many hospitals call the treatments by the name of the manufacturer rather than calling it SRS or SBRT. Brand names for these treatments include Axesse, Cyberknife, Gamma Knife, Novalis, Primatom, Synergy, X-Knife, TomoTherapy, Trilogy and Truebeam. This list changes as equipment manufacturers continue to develop new, specialized technologies to treat cancers.

Virtual simulation, and 3-dimensional conformal radiation therapy

The planning of radiation therapy treatment has been revolutionized by the ability to delineate tumors and adjacent normal structures in three dimensions using specialized CT and/or MRI scanners and planning software.

Virtual simulation, the most basic form of planning, allows more accurate placement of radiation beams than is possible using conventional X-rays, where soft-tissue structures are often difficult to assess and normal tissues difficult to protect.

An enhancement of virtual simulation is 3-dimensional conformal radiation therapy (3DCRT), in which the profile of each radiation beam is shaped to fit the profile of the target from a beam's eye view (BEV) using a multileaf collimator (MLC) and a variable number of beams. When the treatment volume conforms to the shape of the tumor, the relative toxicity of radiation to the surrounding normal tissues is reduced, allowing a higher dose of radiation to be delivered to the tumor than conventional techniques would allow.

Intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT)

Intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) is an advanced type of high-precision radiation that is the next generation of 3DCRT. IMRT also improves the ability to conform the treatment volume to concave tumor shapes, for example when the tumor is wrapped around a vulnerable structure such as the spinal cord or a major organ or blood vessel. Computer-controlled X-ray accelerators distribute precise radiation doses to malignant tumors or specific areas within the tumor. The pattern of radiation delivery is determined using highly tailored computing applications to perform optimization and treatment simulation (Treatment Planning). The radiation dose is consistent with the 3-D shape of the tumor by controlling, or modulating, the radiation beam's intensity. The radiation dose intensity is elevated near the gross tumor volume while radiation among the neighboring normal tissues is decreased or avoided completely. This results in better tumor targeting, lessened side effects, and improved treatment outcomes than even 3DCRT.

3DCRT is still used extensively for many body sites but the use of IMRT is growing in more complicated body sites such as CNS, head and neck, prostate, breast, and lung. Unfortunately, IMRT is limited by its need for additional time from experienced medical personnel. This is because physicians must manually delineate the tumors one CT image at a time through the entire disease site which can take much longer than 3DCRT preparation. Then, medical physicists and dosimetrists must be engaged to create a viable treatment plan. Also, the IMRT technology has only been used commercially since the late 1990s even at the most advanced cancer centers, so radiation oncologists who did not learn it as part of their residency programs must find additional sources of education before implementing IMRT.

Proof of improved survival benefit from either of these two techniques over conventional radiation therapy (2DXRT) is growing for many tumor sites, but the ability to reduce toxicity is generally accepted. This is particularly the case for head and neck cancers in a series of pivotal trials performed by Professor Christopher Nutting of the Royal Marsden Hospital. Both techniques enable dose escalation, potentially increasing usefulness. There has been some concern, particularly with IMRT, about increased exposure of normal tissue to radiation and the consequent potential for secondary malignancy. Overconfidence in the accuracy of imaging may increase the chance of missing lesions that are invisible on the planning scans (and therefore not included in the treatment plan) or that move between or during a treatment (for example, due to respiration or inadequate patient immobilization). New techniques are being developed to better control this uncertainty – for example, real-time imaging combined with real-time adjustment of the therapeutic beams. This new technology is called image-guided radiation therapy or four-dimensional radiation therapy.

Another technique is the real-time tracking and localization of one or more small implantable electric devices implanted inside or close to the tumor. There are various types of medical implantable devices that are used for this purpose. It can be a magnetic transponder which senses the magnetic field generated by several transmitting coils, and then transmits the measurements back to the positioning system to determine the location. The implantable device can also be a small wireless transmitter sending out an RF signal which then will be received by a sensor array and used for localization and real-time tracking of the tumor position.

A well-studied issue with IMRT is the "tongue and groove effect" which results in unwanted underdosing, due to irradiating through extended tongues and grooves of overlapping MLC (multileaf collimator) leaves. While solutions to this issue have been developed, which either reduce the TG effect to negligible amounts or remove it completely, they depend upon the method of IMRT being used and some of them carry costs of their own. Some texts distinguish "tongue and groove error" from "tongue or groove error", according as both or one side of the aperture is occluded.

Volumetric modulated arc therapy (VMAT)

Volumetric modulated arc therapy (VMAT) is a radiation technique introduced in 2007 which can achieve highly conformal dose distributions on target volume coverage and sparing of normal tissues. The specificity of this technique is to modify three parameters during the treatment. VMAT delivers radiation by rotating gantry (usually 360° rotating fields with one or more arcs), changing speed and shape of the beam with a multileaf collimator (MLC) ("sliding window" system of moving) and fluence output rate (dose rate) of the medical linear accelerator. VMAT has an advantage in patient treatment, compared with conventional static field intensity modulated radiotherapy (IMRT), of reduced radiation delivery times. Comparisons between VMAT and conventional IMRT for their sparing of healthy tissues and Organs at Risk (OAR) depends upon the cancer type. In the treatment of nasopharyngeal, oropharyngeal and hypopharyngeal carcinomas VMAT provides equivalent or better protection of the organ at risk (OAR). In the treatment of prostate cancer the OAR protection result is mixed with some studies favoring VMAT, others favoring IMRT.

Temporally feathered radiation therapy (TFRT)

Temporally feathered radiation therapy (TFRT) is a radiation technique introduced in 2018 which aims to use the inherent non-linearities in normal tissue repair to allow for sparing of these tissues without affecting the dose delivered to the tumor. The application of this technique, which has yet to be automated, has been described carefully to enhance the ability of departments to perform it, and in 2021 it was reported as feasible in a small clinical trial, though its efficacy has yet to be formally studied.

Automated planning

Automated treatment planning has become an integrated part of radiotherapy treatment planning. There are in general two approaches of automated planning. 1) Knowledge based planning where the treatment planning system has a library of high quality plans, from which it can predict the target and dose-volume histogram of the organ at risk. 2) The other approach is commonly called protocol based planning, where the treatment planning system tried to mimic an experienced treatment planner and through an iterative process evaluates the plan quality from on the basis of the protocol.

Particle therapy

Main article: Particle therapyIn particle therapy (proton therapy being one example), energetic ionizing particles (protons or carbon ions) are directed at the target tumor. The dose increases while the particle penetrates the tissue, up to a maximum (the Bragg peak) that occurs near the end of the particle's range, and it then drops to (almost) zero. The advantage of this energy deposition profile is that less energy is deposited into the healthy tissue surrounding the target tissue.

Auger therapy

Main article: Auger therapyAuger therapy (AT) makes use of a very high dose of ionizing radiation in situ that provides molecular modifications at an atomic scale. AT differs from conventional radiation therapy in several aspects; it neither relies upon radioactive nuclei to cause cellular radiation damage at a cellular dimension, nor engages multiple external pencil-beams from different directions to zero-in to deliver a dose to the targeted area with reduced dose outside the targeted tissue/organ locations. Instead, the in situ delivery of a very high dose at the molecular level using AT aims for in situ molecular modifications involving molecular breakages and molecular re-arrangements such as a change of stacking structures as well as cellular metabolic functions related to the said molecule structures.

Motion compensation

In many types of external beam radiotherapy, motion can negatively impact the treatment delivery by moving target tissue out of, or other healthy tissue into, the intended beam path. Some form of patient immobilisation is common, to prevent the large movements of the body during treatment, however this cannot prevent all motion, for example as a result of breathing. Several techniques have been developed to account for motion like this. Deep inspiration breath-hold (DIBH) is commonly used for breast treatments where it is important to avoid irradiating the heart. In DIBH the patient holds their breath after breathing in to provide a stable position for the treatment beam to be turned on. This can be done automatically using an external monitoring system such as a spirometer or a camera and markers. The same monitoring techniques, as well as 4DCT imaging, can also be for respiratory gated treatment, where the patient breathes freely and the beam is only engaged at certain points in the breathing cycle. Other techniques include using 4DCT imaging to plan treatments with margins that account for motion, and active movement of the treatment couch, or beam, to follow motion.

Contact X-ray brachytherapy

Contact X-ray brachytherapy (also called "CXB", "electronic brachytherapy" or the "Papillon Technique") is a type of radiation therapy using low energy (50 kVp) kilovoltage X-rays applied directly to the tumor to treat rectal cancer. The process involves endoscopic examination first to identify the tumor in the rectum and then inserting treatment applicator on the tumor through the anus into the rectum and placing it against the cancerous tissue. Finally, treatment tube is inserted into the applicator to deliver high doses of X-rays (30Gy) emitted directly onto the tumor at two weekly intervals for three times over four weeks period. It is typically used for treating early rectal cancer in patients who may not be candidates for surgery. A 2015 NICE review found the main side effect to be bleeding that occurred in about 38% of cases, and radiation-induced ulcer which occurred in 27% of cases.

Brachytherapy (sealed source radiotherapy)

Main article: Brachytherapy

Brachytherapy is delivered by placing radiation source(s) inside or next to the area requiring treatment. Brachytherapy is commonly used as an effective treatment for cervical, prostate, breast, and skin cancer and can also be used to treat tumors in many other body sites.

In brachytherapy, radiation sources are precisely placed directly at the site of the cancerous tumor. This means that the irradiation only affects a very localized area – exposure to radiation of healthy tissues further away from the sources is reduced. These characteristics of brachytherapy provide advantages over external beam radiation therapy – the tumor can be treated with very high doses of localized radiation, whilst reducing the probability of unnecessary damage to surrounding healthy tissues. A course of brachytherapy can often be completed in less time than other radiation therapy techniques. This can help reduce the chance of surviving cancer cells dividing and growing in the intervals between each radiation therapy dose.

As one example of the localized nature of breast brachytherapy, the SAVI device delivers the radiation dose through multiple catheters, each of which can be individually controlled. This approach decreases the exposure of healthy tissue and resulting side effects, compared both to external beam radiation therapy and older methods of breast brachytherapy.

Radionuclide therapy

Main article: Radionuclide therapyRadionuclide therapy (also known as systemic radioisotope therapy, radiopharmaceutical therapy, or molecular radiotherapy), is a form of targeted therapy. Targeting can be due to the chemical properties of the isotope such as radioiodine which is specifically absorbed by the thyroid gland a thousandfold better than other bodily organs. Targeting can also be achieved by attaching the radioisotope to another molecule or antibody to guide it to the target tissue. The radioisotopes are delivered through infusion (into the bloodstream) or ingestion. Examples are the infusion of metaiodobenzylguanidine (MIBG) to treat neuroblastoma, of oral iodine-131 to treat thyroid cancer or thyrotoxicosis, and of hormone-bound lutetium-177 and yttrium-90 to treat neuroendocrine tumors (peptide receptor radionuclide therapy).

Another example is the injection of radioactive yttrium-90 or holmium-166 microspheres into the hepatic artery to radioembolize liver tumors or liver metastases. These microspheres are used for the treatment approach known as selective internal radiation therapy. The microspheres are approximately 30 μm in diameter (about one-third of a human hair) and are delivered directly into the artery supplying blood to the tumors. These treatments begin by guiding a catheter up through the femoral artery in the leg, navigating to the desired target site and administering treatment. The blood feeding the tumor will carry the microspheres directly to the tumor enabling a more selective approach than traditional systemic chemotherapy. There are currently three different kinds of microspheres: SIR-Spheres, TheraSphere and QuiremSpheres.

A major use of systemic radioisotope therapy is in the treatment of bone metastasis from cancer. The radioisotopes travel selectively to areas of damaged bone, and spare normal undamaged bone. Isotopes commonly used in the treatment of bone metastasis are radium-223, strontium-89 and samarium (Sm) lexidronam.

In 2002, the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved ibritumomab tiuxetan (Zevalin), which is an anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody conjugated to yttrium-90. In 2003, the FDA approved the tositumomab/iodine (I) tositumomab regimen (Bexxar), which is a combination of an iodine-131 labelled and an unlabelled anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody. These medications were the first agents of what is known as radioimmunotherapy, and they were approved for the treatment of refractory non-Hodgkin's lymphoma.

Intraoperative radiotherapy

Main article: Intraoperative radiation therapyIntraoperative radiation therapy (IORT) is applying therapeutic levels of radiation to a target area, such as a cancer tumor, while the area is exposed during surgery.

Rationale

The rationale for IORT is to deliver a high dose of radiation precisely to the targeted area with minimal exposure of surrounding tissues which are displaced or shielded during the IORT. Conventional radiation techniques such as external beam radiotherapy (EBRT) following surgical removal of the tumor have several drawbacks: The tumor bed where the highest dose should be applied is frequently missed due to the complex localization of the wound cavity even when modern radiotherapy planning is used. Additionally, the usual delay between the surgical removal of the tumor and EBRT may allow a repopulation of the tumor cells. These potentially harmful effects can be avoided by delivering the radiation more precisely to the targeted tissues leading to immediate sterilization of residual tumor cells. Another aspect is that wound fluid has a stimulating effect on tumor cells. IORT was found to inhibit the stimulating effects of wound fluid.

History

Medicine has used radiation therapy as a treatment for cancer for more than 100 years, with its earliest roots traced from the discovery of X-rays in 1895 by Wilhelm Röntgen. Emil Grubbe of Chicago was possibly the first American physician to use X-rays to treat cancer, beginning in 1896.

The field of radiation therapy began to grow in the early 1900s largely due to the groundbreaking work of Nobel Prize–winning scientist Marie Curie (1867–1934), who discovered the radioactive elements polonium and radium in 1898. This began a new era in medical treatment and research. Through the 1920s the hazards of radiation exposure were not understood, and little protection was used. Radium was believed to have wide curative powers and radiotherapy was applied to many diseases.

Prior to World War 2, the only practical sources of radiation for radiotherapy were radium, its "emanation", radon gas, and the X-ray tube. External beam radiotherapy (teletherapy) began at the turn of the century with relatively low voltage (<150 kV) X-ray machines. It was found that while superficial tumors could be treated with low voltage X-rays, more penetrating, higher energy beams were required to reach tumors inside the body, requiring higher voltages. Orthovoltage X-rays, which used tube voltages of 200-500 kV, began to be used during the 1920s. To reach the most deeply buried tumors without exposing intervening skin and tissue to dangerous radiation doses required rays with energies of 1 MV or above, called "megavolt" radiation. Producing megavolt X-rays required voltages on the X-ray tube of 3 to 5 million volts, which required huge expensive installations. Megavoltage X-ray units were first built in the late 1930s but because of cost were limited to a few institutions. One of the first, installed at St. Bartholomew's hospital, London in 1937 and used until 1960, used a 30 foot long X-ray tube and weighed 10 tons. Radium produced megavolt gamma rays, but was extremely rare and expensive due to its low occurrence in ores. In 1937 the entire world supply of radium for radiotherapy was 50 grams, valued at £800,000, or $50 million in 2005 dollars.

The invention of the nuclear reactor in the Manhattan Project during World War 2 made possible the production of artificial radioisotopes for radiotherapy. Cobalt therapy, teletherapy machines using megavolt gamma rays emitted by cobalt-60, a radioisotope produced by irradiating ordinary cobalt metal in a reactor, revolutionized the field between the 1950s and the early 1980s. Cobalt machines were relatively cheap, robust and simple to use, although due to its 5.27 year half-life the cobalt had to be replaced about every 5 years.

Medical linear particle accelerators, developed since the 1940s, began replacing X-ray and cobalt units in the 1980s and these older therapies are now declining. The first medical linear accelerator was used at the Hammersmith Hospital in London in 1953. Linear accelerators can produce higher energies, have more collimated beams, and do not produce radioactive waste with its attendant disposal problems like radioisotope therapies.

With Godfrey Hounsfield's invention of computed tomography (CT) in 1971, three-dimensional planning became a possibility and created a shift from 2-D to 3-D radiation delivery. CT-based planning allows physicians to more accurately determine the dose distribution using axial tomographic images of the patient's anatomy. The advent of new imaging technologies, including magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in the 1970s and positron emission tomography (PET) in the 1980s, has moved radiation therapy from 3-D conformal to intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) and to image-guided radiation therapy tomotherapy. These advances allowed radiation oncologists to better see and target tumors, which have resulted in better treatment outcomes, more organ preservation and fewer side effects.

While access to radiotherapy is improving globally, more than half of patients in low and middle income countries still do not have available access to the therapy as of 2017.

See also

- Beam spoiler

- Cancer and nausea

- Fast neutron therapy

- Neutron capture therapy of cancer

- Particle beam

- Radiation therapist

- Selective internal radiation therapy

- Treatment of cancer

References

- ^ Yerramilli D, Xu AJ, Gillespie EF, Shepherd AF, Beal K, Gomez D, et al. (2020-07-01). "Palliative Radiation Therapy for Oncologic Emergencies in the Setting of COVID-19: Approaches to Balancing Risks and Benefits". Advances in Radiation Oncology. 5 (4): 589–594. doi:10.1016/j.adro.2020.04.001. PMC 7194647. PMID 32363243.

- Rades D, Stalpers LJ, Veninga T, Schulte R, Hoskin PJ, Obralic N, et al. (May 2005). "Evaluation of five radiation schedules and prognostic factors for metastatic spinal cord compression". Journal of Clinical Oncology. 23 (15): 3366–3375. doi:10.1200/JCO.2005.04.754. PMID 15908648.

- Rades D, Panzner A, Rudat V, Karstens JH, Schild SE (November 2011). "Dose escalation of radiotherapy for metastatic spinal cord compression (MSCC) in patients with relatively favorable survival prognosis". Strahlentherapie und Onkologie. 187 (11): 729–735. doi:10.1007/s00066-011-2266-y. PMID 22037654. S2CID 19991034.

- Rades D, Šegedin B, Conde-Moreno AJ, Garcia R, Perpar A, Metz M, et al. (February 2016). "Radiotherapy With 4 Gy × 5 Versus 3 Gy × 10 for Metastatic Epidural Spinal Cord Compression: Final Results of the SCORE-2 Trial (ARO 2009/01)". Journal of Clinical Oncology. 34 (6): 597–602. doi:10.1200/JCO.2015.64.0862. PMID 26729431.

- ^ Cooper, Jeffrey S.; Hanley, Mary E.; Hendriksen, Stephen; Robins, Marc (August 30, 2022). "Hyperbaric Treatment of Delayed Radiation Injury". National Center for Biotechnology Information. PMID 29261879. Retrieved 23 July 2023.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - CK Bomford, IH Kunkler, J Walter. Walter and Miller's Textbook of Radiation therapy (6th Ed), p311

- "Radiosensitivity". GP Notebook.

- Tidy C (23 December 2015). Bonsall A (ed.). "Radiation therapy- what GPs need to know". patient.co.uk.

- Maverakis E, Cornelius LA, Bowen GM, Phan T, Patel FB, Fitzmaurice S, et al. (May 2015). "Metastatic melanoma - a review of current and future treatment options". Acta Dermato-Venereologica. 95 (5): 516–524. doi:10.2340/00015555-2035. PMID 25520039.

- ^ Camphausen KA, Lawrence RC (2008). "Principles of Radiation Therapy". In Pazdur R, Wagman LD, Camphausen KA, Hoskins WJ (eds.). Cancer Management: A Multidisciplinary Approach (11th ed.). UBM Medica LLC. Archived from the original on 15 May 2009.

- Falls KC, Sharma RA, Lawrence YR, Amos RA, Advani SJ, Ahmed MM, et al. (October 2018). "Radiation-Drug Combinations to Improve Clinical Outcomes and Reduce Normal Tissue Toxicities: Current Challenges and New Approaches: Report of the Symposium Held at the 63rd Annual Meeting of the Radiation Research Society, 15-18 October 2017; Cancun, Mexico". Radiation Research. 190 (4). Europe PMC: 350–360. Bibcode:2018RadR..190..350F. doi:10.1667/rr15121.1. PMC 6322391. PMID 30280985.

- Seidlitz A, Combs SE, Debus J, Baumann M (2016). "Practice points for radiation oncology". In Kerr DJ, Haller DG, van de Velde CJ, Baumann M (eds.). Oxford Textbook of Oncology. Oxford University Press. p. 173. ISBN 9780191065101.

- Darby S, McGale P, Correa C, Taylor C, Arriagada R, Clarke M, et al. (November 2011). "Effect of radiotherapy after breast-conserving surgery on 10-year recurrence and 15-year breast cancer death: meta-analysis of individual patient data for 10,801 women in 17 randomised trials". Lancet. 378 (9804): 1707–1716. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61629-2. PMC 3254252. PMID 22019144.

- Reyngold M, Parikh P, Crane CH (June 2019). "Ablative radiation therapy for locally advanced pancreatic cancer: techniques and results". Radiation Oncology. 14 (1): 95. doi:10.1186/s13014-019-1309-x. PMC 6555709. PMID 31171025.

- Mahmood SS, Nohria A (July 2016). "Cardiovascular Complications of Cranial and Neck Radiation". Current Treatment Options in Cardiovascular Medicine. 18 (7): 45. doi:10.1007/s11936-016-0468-4. PMID 27181400. S2CID 23888595.

- "Radiation Therapy for Breast Cancer: Possible Side Effects". Rtanswers.com. 2012-03-15. Archived from the original on 2012-03-01. Retrieved 2012-04-20.

- Lee VH, Ng SC, Leung TW, Au GK, Kwong DL (September 2012). "Dosimetric predictors of radiation-induced acute nausea and vomiting in IMRT for nasopharyngeal cancer". International Journal of Radiation Oncology, Biology, Physics. 84 (1): 176–182. doi:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.10.010. PMID 22245210.

- "Side Effects of Radiation Therapy - Caring4Cancer". Archived from the original on 2012-03-30. Retrieved 2012-05-02. Common radiation side effects

- "Radiation Therapy Side Effects and Ways to Manage them". National Cancer Institute. 2007-04-20. Retrieved 2012-05-02.

- Hall EJ (2000). Radiobiology for the radiologist. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams Wilkins. p. 351. ISBN 9780781726498.

- Carretero C, Munoz-Navas M, Betes M, Angos R, Subtil JC, Fernandez-Urien I, et al. (June 2007). "Gastroduodenal injury after radioembolization of hepatic tumors". The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 102 (6): 1216–1220. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01172.x. hdl:10171/27487. PMID 17355414. S2CID 121385.

- Yip D, Allen R, Ashton C, Jain S (March 2004). "Radiation-induced ulceration of the stomach secondary to hepatic embolization with radioactive yttrium microspheres in the treatment of metastatic colon cancer". Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 19 (3): 347–349. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1746.2003.03322.x. PMID 14748889. S2CID 39434006.

- Murthy R, Brown DB, Salem R, Meranze SG, Coldwell DM, Krishnan S, et al. (April 2007). "Gastrointestinal complications associated with hepatic arterial Yttrium-90 microsphere therapy". Journal of Vascular and Interventional Radiology. 18 (4): 553–61, quiz 562. doi:10.1016/j.jvir.2007.02.002. PMID 17446547.

- Arepally A, Chomas J, Kraitchman D, Hong K (April 2013). "Quantification and reduction of reflux during embolotherapy using an antireflux catheter and tantalum microspheres: ex vivo analysis". Journal of Vascular and Interventional Radiology. 24 (4): 575–580. doi:10.1016/j.jvir.2012.12.018. PMID 23462064.

- ^ Henson CC, Burden S, Davidson SE, Lal S (November 2013). "Nutritional interventions for reducing gastrointestinal toxicity in adults undergoing radical pelvic radiotherapy". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (11): CD009896. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd009896.pub2. PMID 24282062.

- Meek AG (December 1998). "Breast radiotherapy and lymphedema". Cancer. 83 (12 Suppl American): 2788–2797. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19981215)83:12B+<2788::AID-CNCR27>3.0.CO;2-I. PMID 9874399. S2CID 23963700.

- Kamran SC, Berrington de Gonzalez A, Ng A, Haas-Kogan D, Viswanathan AN (June 2016). "Therapeutic radiation and the potential risk of second malignancies". Cancer. 122 (12): 1809–1821. doi:10.1002/cncr.29841. PMID 26950597.

- Dracham CB, Shankar A, Madan R (June 2018). "Radiation induced secondary malignancies: a review article". Radiation Oncology Journal. 36 (2): 85–94. doi:10.3857/roj.2018.00290. PMC 6074073. PMID 29983028.

At present after surviving from a primary malignancy, 17%–19% patients develop second malignancy. ... contributes to only about 5% of the total treatment related second malignancies. However the incidence of only radiation on second malignancies is difficult to estimate...

- Mohamad O, Tabuchi T, Nitta Y, Nomoto A, Sato A, Kasuya G, et al. (May 2019). "Risk of subsequent primary cancers after carbon ion radiotherapy, photon radiotherapy, or surgery for localised prostate cancer: a propensity score-weighted, retrospective, cohort study". The Lancet. Oncology. 20 (5): 674–685. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30931-8. PMID 30885458. S2CID 83461547.

- Facoetti A, Barcellini A, Valvo F, Pullia M (September 2019). "The Role of Particle Therapy in the Risk of Radio-induced Second Tumors: A Review of the Literature". Anticancer Research. 39 (9): 4613–4617. doi:10.21873/anticanres.13641. PMID 31519558. S2CID 202572547.

- Ohno T, Okamoto M (June 2019). "Carbon ion radiotherapy as a treatment modality for paediatric cancers". The Lancet. Child & Adolescent Health. 3 (6): 371–372. doi:10.1016/S2352-4642(19)30106-3. PMID 30948250. S2CID 96433438.

- Taylor CW, Nisbet A, McGale P, Darby SC (December 2007). "Cardiac exposures in breast cancer radiotherapy: 1950s-1990s". International Journal of Radiation Oncology, Biology, Physics. 69 (5): 1484–1495. doi:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.05.034. PMID 18035211.

- ^ Weintraub NL, Jones WK, Manka D (March 2010). "Understanding radiation-induced vascular disease". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 55 (12): 1237–1239. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2009.11.053. PMC 3807611. PMID 20298931.

- ^ Benveniste, Marcelo F.; Gomez, Daniel; Carter, Brett W.; Betancourt Cuellar, Sonia L.; Shroff, Girish S.; Benveniste, Ana Paula; Odisio, Erika G.; Marom, Edith M. (March 7, 2019). "Recognizing Radiation Therapy–related Complications in the Chest". RadioGraphics. 39 (2): 353. doi:10.1148/rg.2019180061. PMID 30844346. S2CID 73477338. Retrieved 24 August 2023.

- ^ Klee NS, McCarthy CG, Martinez-Quinones P, Webb RC (November 2017). "Out of the frying pan and into the fire: damage-associated molecular patterns and cardiovascular toxicity following cancer therapy". Therapeutic Advances in Cardiovascular Disease. 11 (11): 297–317. doi:10.1177/1753944717729141. PMC 5933669. PMID 28911261.

- Belzile-Dugas E, Eisenberg MJ (September 2021). "Radiation-Induced Cardiovascular Disease: Review of an Underrecognized Pathology". J Am Heart Assoc. 10 (18): e021686. doi:10.1161/JAHA.121.021686. PMC 8649542. PMID 34482706.

- "Late Effects of Treatment for Childhood Cancer". National Cancer Institute. 12 April 2012. Retrieved 7 June 2012.

- Hauer-Jensen M, Denham JW, Andreyev HJ (August 2014). "Radiation enteropathy--pathogenesis, treatment and prevention". Nature Reviews. Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 11 (8): 470–479. doi:10.1038/nrgastro.2014.46. PMC 4346191. PMID 24686268.

- Fuccio L, Guido A, Andreyev HJ (December 2012). "Management of intestinal complications in patients with pelvic radiation disease". Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 10 (12): 1326–1334.e4. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2012.07.017. PMID 22858731.

- ^ Roy, Soumyajit; Salerno, Kilian E.; Citrin, Deborah E. (April 2021). "Biology of Radiation Induced Lung Injury". Seminars in Radiation Oncology. 31 (2). Elsevier Inc.: 155–161. doi:10.1016/j.semradonc.2020.11.006. PMC 7905704. PMID 33610273. Retrieved 1 December 2024.

- ^ Custodio C, Andrews CC (August 1, 2017). "Radiation Plexopathy". American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation.

- ^ Delanian S, Lefaix JL, Pradat PF (December 2012). "Radiation-induced neuropathy in cancer survivors". Radiotherapy and Oncology. 105 (3): 273–282. doi:10.1016/j.radonc.2012.10.012. PMID 23245644.

- Davalos, Long; Arya, Kapil; Kushlaf, Hani (July 15, 2023). Abnormal Spontaneous Electromyographic Activity. Treasure Island, Florida: StatPearls Publishing. PMID 29494068. Retrieved 6 March 2024.

- Song, Suying L (September 30, 2021). "Myokymia Clinical Presentation". emedicine.medscape.com. Retrieved 7 March 2024.

- ^ Gupta G, Jumah FR, Raju B, Roychowdhury S, Nanda A, Schneck MJ, Vincent FM, Janss A (2019-11-09). Talavera F, Kattah JC, Nelson Jr SL (eds.). "Radiation Necrosis: Background, Pathophysiology, Epidemiology". Emedicine.

- Nieder C, Milas L, Ang KK (July 2000). "Tissue tolerance to reirradiation". Seminars in Radiation Oncology. 10 (3): 200–209. doi:10.1053/srao.2000.6593. PMID 11034631.

- ^ Arnon J, Meirow D, Lewis-Roness H, Ornoy A (2001). "Genetic and teratogenic effects of cancer treatments on gametes and embryos". Human Reproduction Update. 7 (4): 394–403. doi:10.1093/humupd/7.4.394. PMID 11476352.

- ^ Fernandez A, Brada M, Zabuliene L, Karavitaki N, Wass JA (September 2009). "Radiation-induced hypopituitarism". Endocrine-Related Cancer. 16 (3): 733–772. doi:10.1677/ERC-08-0231. PMID 19498038.

- Sklar, CA; Antal, Z; Chemaitilly, W; Cohen, LE; Follin, C; Meacham, LR; Murad, MH (1 August 2018). "Hypothalamic-Pituitary and Growth Disorders in Survivors of Childhood Cancer: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 103 (8): 2761–2784. doi:10.1210/jc.2018-01175. PMID 29982476. S2CID 51601915.

- Bogdanich W, Ruiz RB (25 February 2010). "Missouri Hospital Reports Errors in Radiation Doses". The New York Times. Retrieved 26 February 2010.

- "What Questions Should I Ask My Doctor?: Questions to ask after treatment ends". Rtanswers.com. 2010-09-22. Archived from the original on 2012-04-12. Retrieved 2012-04-20.

- Eaton C, Seegenschmiedt MH, Bayat A, Gabbiani G, Werker P, Wach W (2012). Dupuytren's Disease and Related Hyperproliferative Disorders: Principles, Research, and Clinical Perspectives. Springer. pp. 355–364. ISBN 978-3-642-22696-0.

- Vitale I, Galluzzi L, Castedo M, Kroemer G (June 2011). "Mitotic catastrophe: a mechanism for avoiding genomic instability". Nature Reviews. Molecular Cell Biology. 12 (6): 385–392. doi:10.1038/nrm3115. PMID 21527953. S2CID 22483746.

- Harrison LB, Chadha M, Hill RJ, Hu K, Shasha D (2002). "Impact of tumor hypoxia and anemia on radiation therapy outcomes". The Oncologist. 7 (6): 492–508. doi:10.1634/theoncologist.7-6-492. PMID 12490737. S2CID 46682896.

- Sheehan JP, Shaffrey ME, Gupta B, Larner J, Rich JN, Park DM (October 2010). "Improving the radiosensitivity of radioresistant and hypoxic glioblastoma". Future Oncology. 6 (10): 1591–1601. doi:10.2217/fon.10.123. PMID 21062158.

- Curtis RE, Freedman DM, Ron E, Ries LAG, Hacker DG, Edwards BK, Tucker MA, Fraumeni JF Jr. (eds). New Malignancies Among Cancer Survivors: SEER Cancer Registries, 1973–2000. National Cancer Institute. NIH Publ. No. 05-5302. Bethesda, MD, 2006.

- Dracham CB, Shankar A, Madan R (June 2018). "Radiation induced secondary malignancies: a review article". Radiation Oncology Journal. 36 (2): 85–94. doi:10.3857/roj.2018.00290. PMC 6074073. PMID 29983028.

- Baldock C, De Deene Y, Doran S, Ibbott G, Jirasek A, Lepage M, et al. (March 2010). "Polymer gel dosimetry". Physics in Medicine and Biology. 55 (5): R1-63. Bibcode:2010PMB....55R...1B. doi:10.1088/0031-9155/55/5/r01. PMC 3031873. PMID 20150687.

- Ang KK (October 1998). "Altered fractionation trials in head and neck cancer". Seminars in Radiation Oncology. 8 (4): 230–236. doi:10.1016/S1053-4296(98)80020-9. PMID 9873100.

- ^ American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine, "Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question", Choosing Wisely: an initiative of the ABIM Foundation, American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine, retrieved August 1, 2013, which cites

- Lutz S, Berk L, Chang E, Chow E, Hahn C, Hoskin P, et al. (March 2011). "Palliative radiotherapy for bone metastases: an ASTRO evidence-based guideline". International Journal of Radiation Oncology, Biology, Physics. 79 (4): 965–976. doi:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.11.026. PMID 21277118.

- Scott JG, Berglund A, Schell MJ, Mihaylov I, Fulp WJ, Yue B, et al. (February 2017). "A genome-based model for adjusting radiotherapy dose (GARD): a retrospective, cohort-based study". The Lancet. Oncology. 18 (2): 202–211. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30648-9. PMC 7771305. PMID 27993569.

- Lacombe J, Azria D, Mange A, Solassol J (February 2013). "Proteomic approaches to identify biomarkers predictive of radiotherapy outcomes". Expert Review of Proteomics. 10 (1): 33–42. doi:10.1586/epr.12.68. PMID 23414358. S2CID 39888421.

- Scott JG, Sedor G, Ellsworth P, Scarborough JA, Ahmed KA, Oliver DE, et al. (September 2021). "Pan-cancer prediction of radiotherapy benefit using genomic-adjusted radiation dose (GARD): a cohort-based pooled analysis". The Lancet. Oncology. 22 (9): 1221–1229. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00347-8. PMID 34363761.

- Daly MJ (March 2009). "A new perspective on radiation resistance based on Deinococcus radiodurans". Nature Reviews. Microbiology. 7 (3): 237–245. doi:10.1038/nrmicro2073. PMID 19172147. S2CID 17787568.

- Sharma A, Gaidamakova EK, Grichenko O, Matrosova VY, Hoeke V, Klimenkova P, et al. (October 2017). "Across the tree of life, radiation resistance is governed by antioxidant Mn, gauged by paramagnetic resonance". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 114 (44): E9253 – E9260. Bibcode:2017PNAS..114E9253S. doi:10.1073/pnas.1713608114. PMC 5676931. PMID 29042516.

- Doble PA, Miklos GL (September 2018). "Distributions of manganese in diverse human cancers provide insights into tumour radioresistance". Metallomics. 10 (9): 1191–1210. doi:10.1039/c8mt00110c. hdl:10453/128630. PMID 30027971.

- Espenel S, Chargari C, Blanchard P, Bockel S, Morel D, Rivera S, et al. (August 2022). "Practice changing data and emerging concepts from recent radiation therapy randomised clinical trials". European Journal of Cancer. 171. Elsevier BV: 242–258. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2022.04.038. PMID 35779346.

- Nelson R (17 August 2022). "The 'Great Dynamism' of Radiation Oncology". Medscape.

- Hill R, Healy B, Holloway L, Kuncic Z, Thwaites D, Baldock C (March 2014). "Advances in kilovoltage x-ray beam dosimetry". Physics in Medicine and Biology. 59 (6): R183 – R231. Bibcode:2014PMB....59R.183H. doi:10.1088/0031-9155/59/6/R183. PMID 24584183. S2CID 18082594.

- ^ Thwaites DI, Tuohy JB (July 2006). "Back to the future: the history and development of the clinical linear accelerator". Physics in Medicine and Biology. 51 (13): R343 – R362. Bibcode:2006PMB....51R.343T. doi:10.1088/0031-9155/51/13/R20. PMID 16790912. S2CID 7672187.

- Lagendijk JJ, Raaymakers BW, Van den Berg CA, Moerland MA, Philippens ME, van Vulpen M (November 2014). "MR guidance in radiotherapy". Physics in Medicine and Biology. 59 (21): R349 – R369. Bibcode:2014PMB....59R.349L. doi:10.1088/0031-9155/59/21/R349. PMID 25322150. S2CID 2591566.

- "American Society for Radiation Oncology" (PDF). Astro.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-06-13. Retrieved 2012-04-20.

- "Treatment Types: Stereotactic Radiation Therapy". Rtanswers.com. 2010-01-04. Archived from the original on 2012-05-09. Retrieved 2012-04-20.