| This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. Please help to improve this article by introducing more precise citations. (February 2013) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

| Ipe Ivandić | |

|---|---|

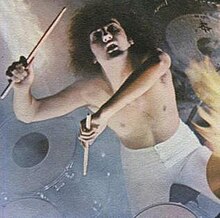

Ivandić at the time of Šta bi dao da si na mom mjestu album release Ivandić at the time of Šta bi dao da si na mom mjestu album release | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Goran Ivandić |

| Born | (1955-12-10)10 December 1955 Vareš, PR Bosnia and Herzegovina, FPR Yugoslavia |

| Died | 12 January 1994(1994-01-12) (aged 38) Belgrade, Serbia, FR Yugoslavia |

| Genres | Rock, progressive rock, hard rock, heavy metal, folk rock, pop rock |

| Occupation | Musician |

| Instrument | Drum kit |

| Years active | 1970–1989 |

| Labels | Jugoton, Diskoton, ZKP RTLJ, Kamarad, Radio Kruševac |

| Formerly of | Jutro |

Goran "Ipe" Ivandić (December 10, 1955 – January 12, 1994) was a Bosnian rock drummer, famous for his work with the band Bijelo Dugme.

Early life

Ivandić was born to father Josip and mother Mirjana in the central Bosnian town of Vareš where his mining engineer father had been assigned for employment by the Yugoslav communist authorities as part of the country's central economic planning. Nicknamed Ipe from an early age, the youngster was raised with an older brother and younger sister Gordana.

Move to Sarajevo

The family moved to Sarajevo in 1960 when Ivandić was four.

While in elementary school, Ivandić simultaneously attended violin classes at a lower music school. However, soon after completing his final music school exam, he abruptly decided he "no longer wanted to bother with violin".

He would soon turn his focus to percussions. In 1970, along with some friends, fourteen-year-old Ivandić founded a music section within the Boško Buha youth centre simply because it was willing to provide free instruments. They named their band Crossroads with Ivandić playing the drums. With the band taking up most of his free time, he started neglecting school and as a result flunked his sophomore year of high school and had to repeat it. He eventually switched to part-time secondary education.

Career

In June 1972, Ivandić went on a three-month summer gig in Trpanj as part of a band called Moby Dick.

After getting back to Sarajevo in fall 1972, the teenager began receiving offers from groups looking for a drummer. He eventually decided to join a band called Rok. Their bandleader, organist Gabor Lenđel, would, later in 1974, go on to establish the hard rock band Teška Industrija on the ashes of Rok.

Jutro

Main article: Jutro (Sarajevo band)Teenage Ivandić was still drumming in Rok during late summer 1973 when Jutro's twenty-three-year-old bandleader Goran Bregović became aware of him. Seeking a replacement for Šento Borovčanin, Bregović immediately presented Ivandić with an offer of joining Jutro. The seventeen-year-old gladly accepted, thus beginning the first of his three stints with what would soon become the most popular band in SFR Yugoslavia. Several months later, on New Year's Eve 1974, Jutro changed their name to Bijelo Dugme.

Bijelo Dugme

Main article: Bijelo DugmeIn October 1976, after recording two hugely successful albums—1974's Kad bi' bio bijelo dugme and 1975's Šta bi dao da si na mom mjestu—as well as playing the accompanying tours, Ivandić received an early call up to serve the mandatory Yugoslav People's Army stint. The call up came at the most inopportune time as the band was getting ready to start recording their third album, but Ivandić had to go nonetheless. Still twenty-years-of-age at the time, he was assigned to a unit stationed in capital city Belgrade. His replacement in the band was Bregović's old companion Milić Vukašinović.

After being discharged early from the army due to getting pronounced "temporarily unable to serve", Ivandić rejoined the band during mid 1977. Mired in deep personality clashes amid a shambolic tour featuring less-than-expected attendance, poor musicianship due to lack of practice, equipment problems, and overall organizational issues, Bijelo Dugme somehow completed the tour before reconvening a month later in August 1977 for a triumphant free open-air concert at Hajdučka Česma in Belgrade before 70,000 spectators.

Side project with Laza Ristovski, leaving Bijelo Dugme, and drug bust

In early 1978, with Bijelo Dugme on hiatus due to band leader Bregović being away in Niš serving his own mandatory army stint, Ivandić and Bijelo Dugme keyboardist Laza Ristovski started working on a side project—album titled Stižemo with their act named Laza i Ipe. The material—composed by Ristovski, arranged by Ipe, with lyrics written by Ranko Boban—was recorded in London throughout February and March 1978 featuring Ivandić, his sister Gordana Ivandić and Goran Kovačević on vocals, Leb i Sol leader Vlatko Stefanovski on guitar, Zlatko Hold on bass, and Ristovski on keyboards. However, the release date kept getting pushed back due to financing issues as they had problems convincing the Jugoton record label to cover their expenses.

Simultaneously, during Bregović's temporary army leaves, the duo—backed up by Bijelo Dugme singer Željko Bebek—initiated multiple internal discussions as they wanted several business matters within the band to be handled differently going forward, specifically writing credits and subsequent revenue sharing. Dissatisfied with Bregović's flat rejection of their demands, Ivandić and Ristovski abandoned Bijelo Dugme altogether in late July 1978 in order to fully commit to their Laza i Ipe project.

Back on the Laza i Ipe front, the money issues with Jugoton were solved by taking the material over to ZKP RTLJ label while some of the money was obtained through Bijelo Dugme bandmate Zoran Redžić. The album Stižemo ended up being promoted very ambitiously with high quality press material. It was also the first time in Yugoslavia that an album's release was scheduled in advance with the date announced publicly—a widely used marketing practice at the time had been to release an album and then promote it once it's already in stores.

Then on September 10, 1978, the day of the album release, while entering his apartment building in Sarajevo, coming back from a walk with his girlfriend, twenty-two-year-old Ivandić was arrested by a plainclothes policeman and taken in for questioning. Ivandić had been set to leave for Belgrade in a matter of hours where Laza was waiting so they can do promotional activities for the album. Instead, Ivandić got charged with a series of drug offenses along with other individuals. He thus began a long court battle that pushed most of his musical activities to the back burner. He even sold his drum kit and went back to his university studies, passing a few exams at the University of Sarajevo's Faculty of Political Sciences where he had been enrolled in the journalism program.

While awaiting sentencing, Ivandić was under a Yugoslavia-wide shadow ban on public performance that included restrictions on being credited publicly. Despite Ivandić not being in Bijelo Dugme at the time of his drug arrest, as a result of the large media scandal that erupted, the band also felt the need to publicly distance themselves from their ex-drummer as the Yugoslav public largely still perceived him as a Bijelo Dugme member. They recorded their next two studio albums—1979's Bitanga i princeza and 1980's Doživjeti stotu—with a new drummer, Điđi Jankelić. Since the authorities of the Yugoslav constituent unit of SR Serbia mostly didn't enforce Ivandić's country-wide ban, he began frequently performing there as a session drummer in order to help his suddenly lacklustre finances due to losing all his sources of income. He participated in the recording sessions of the twenty-two-year-old Slađana Milošević's 1979 debut album Gorim od želje da ubijem noć in PGP-RTB's studios in Belgrade and furthermore appears in the title track video. Showing Ivandić in several frames of the video at this time was considered controversial in Yugoslavia and reportedly required young Milošević to personally intervene with television executives.

Eventually, Ivandić was sentenced by the Sarajevo District Court three-judge council presided over by judge Husein Hubijer to 3+1⁄2 years in prison for "possession of hashish and enabling others to use narcotics". Also sentenced by the council on the same charge were Goran Kovačević to year and a half, Ranko Boban to 1 year. Furthermore, Zlatko Hold got sentenced to six months for obstruction of justice. Ivandić appealed the verdict, and his sentence was reduced to 3 years by the Supreme Court of SR Bosnia-Herzegovina.

He began serving his punishment at the Zenica correctional facility in early 1981. On February 17, 1981, he was transferred to another prison—in Foča—before getting pardoned for the 1982 Republic Day (November 29). In total, he ended up doing about 22 months of prison time.

Return to Dugme

After being released from prison, Ivandić reportedly immediately travelled to SR Slovenia, spending several weeks with a friend without contacting any of his old professional collaborators. By late December 1982, he got tracked down by Bijelo Dugme's manager Raka Marić [sr] and bandleader Bregović who extended an offer of rejoining the band. After Ivandić initially turned them down, they kept on persisting. Several days later Ivandić accepted thus beginning his third stint with the band that would last until 1989 when the band dissolved.

During the mid-1980s he also recorded two albums, Kakav divan dan and Igre slobode, with his long-time girlfriend Amila Sulejmanović [sr]. After the albums' recording, Amila moved to London while Ivandić stopped all side projects and devoted fully to Bijelo Dugme.

It is unclear where he lived after the war started. Most say that he lived in Belgrade but in a 1994 interview for Croatian weekly Globus (conducted days after Ivandić's death), Željko Bebek states Ivandić lived in Vienna, at least at the time they last talked.

Personal life

From his early days at Bijelo Dugme during the mid-1970s, Ivandić was in a relationship with Irhada Muhić (later Sulejmanpašić).

Sometime after his late 1982 prison release, Ivandić began a romantic involvement with Amila Sulejmanović [sr] (later Welland), eight years his junior, whom he would also start collaborating with musically. The relationship ended in 1988 when she moved to London. In 2018, Sulejmanović released her autobiography Ključ bubnja tama, significant portions of which centre around her musical career in Yugoslavia and relationship with Ivandić.

In 1988, Ivandić began a relationship with Dragana Tešić. The two got married in 1990 following the premature end of Bijelo Dugme's 1989 tour that would eventually turn out to be the band's last activity. The couple's son Filip was born in Sarajevo in 1991.

On January 12, 1994, Ivandić died after falling from the 6th floor of the Metropol Hotel in Belgrade (at the time Serbia, FR Yugoslavia). It is generally believed that it was a suicide, but Bebek in the same interview says he has trouble believing it based on his prior knowledge of Ivandić and his habits.

See also

- Izgubljeno dugme [hr], a 2015 documentary about Ipe Ivandić by Renato Tonković, Marijo Vukadin [hr], and Robert Bubalo [hr]

References

- Janjatović, Petar (2007). EX YU ROCK enciklopedija 1960-2006. Belgrade: self-released. p. 33.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on December 20, 2005. Retrieved June 25, 2005.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Goreta, Mirela (December 9, 2014). "Ljudi bliski bubnjaru 'Dugmeta' tvrde: Ipe nije počinio samoubojstvo, glave su ga stajali kamatari". Slobodna Dalmacija. Retrieved April 12, 2015.

- EX YU ROCK enciklopedija 1960–2006, Janjatović Petar; ISBN 978-86-905317-1-4

External links

- Web Site set up in his honour

- U pripremi dokumentarni film o članu „Bjelog dugmeta“, Blic, January 17, 2009

| Bijelo Dugme | |

|---|---|

| |

| Studio albums | |

| Live albums |

|

| Compilation albums |

|

| Box sets |

|

| Collaboration projects | |

| Associated acts | |

| Related articles | |