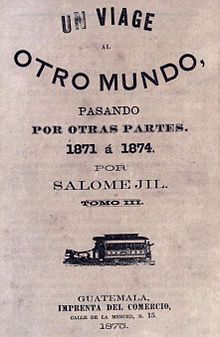

Juan Chapín is a character created by Guatemalan writer José Milla y Vidaurre in his novel Un viaje al otro mundo pasando por otras partes -A trip to the other world, going through other parts-, which he wrote while in exile in Europe after the Liberal revolution of 1871. Milla y Vidaurre had been a close friend of general Rafael Carrera, who had ruled Guatemala until his death in 1865. Milla also worked in the Foreign Minister during Carrera's regime. From 1871 to 1874, Milla visited several countries in North America and Europe and used his character Juan Chapín - to whom he explains everything they come across in Europe - to represent the average Guatemalan of his day.

Character description

José Milla y Vidaurre«...boy of about thirty two years old, round face, clean shaven, medium height, black hair (...), lips a bit thick, that, when open, show two rows of white, strong and even teeth; smile between sad and funny; black eyes where there is something almost malicious and skeptic that contrast with the rest of his appearance, which is relaxed and easy going.»

1875

Milla y Vidaurre started describing the authentic "chapín"- that is, the typical Guatemalan- in his book Cuadros de costumbres -Custom portraits-,: «The real and genuine chapín type, such as it existed at the beginning of this century, it is vanishing, little by little, and maybe after a while it will disappear altogether. The chapín is a group of good qualities and defects, making him very similar in this to the rest of the individuals in the human race, but with the difference that his virtues and drawbacks have certain peculiar character, resulting from special circumstances. He is friendly, a good host, a helping hand, religious, smart; and even though in general he is not talented when it comes to initiative, he is particularly apt to imitate what others have already invented. He has had a hard life and is no coward in the face of danger. Likes to tell tall tales; after the first impressions, his natural good judgment analyzes and discusses, and if, like it often happens, he finds out that we was admiring a low worthy object, he turns his back to it and forgets about his yesterday idol. The chapín is apathetic and customary; he does not go to appointments, and when he does, he is always tardy; he cares about others business a little too much and has an amazing ability to find the funny and ridiculous side of men and things. The true chapín (and here I do not speak about the one that has altered his type by adopting overseas manners), love his country with a passion, frequently understanding for country the city where he was born; and it as attached to his city as a turtle with its shell. For him, Guatemala is better than Paris; we would not change the chocolate for either tea nor coffee (in which he is absolutely right). He likes tamales more than the vol-au-vent, and prefers a "pepián" dish to the most delicious roastbeef. He speaks an antique Spanish: vos, habís, tené, andá; and his conversation is adorned with Guatemalan slang, very expressive and colorful. He eats lunch at two in the afternoon: shaves on Thursdays and Sundays, unless he has a cold, in which case he does not do it even if his life depends on it; he is fifty years old, and he is still being called "niño fulano" -baby Joe-; he has been attending the same evening gathering for the last fifteen years, where he has a chronic love that will last until he or she goes six feet under.»

In the first volume of his novel, Milla y Vidaurre tells the story of his trip by boat to San Francisco and then on to New York City on the transcontinental railroad in 1871.; all his adventures have poignant comments from Juan Chapín. He are some of his reflections:

- About women being in charge of the post office: «Women handling the post office! You are not going to make me swallow that one, even after killing me. If they are extremely curious! They will not leave any single letter unread.»

- After noticing the cosmetics and creams ads along Sierra Nevada: «Look at this people, sir! A thinkg that the day we reach Purgatory (which I hope is the latest possible), we will find on the door the ads of the Yankee doctors, that are trying to sell pills and medicines to the souls there, even!»

- After having to rush eating his lunch so he could hop in a train on time: «:Like half an hour more or less for each stop would mean a great deal at the end of journey!»

Juan Chapín magazine

Guatemalan 1910 Generation was formed, among others, of writers that under the influx of Modernism, started writings on their own. They even had their own magazine: Juan Chapín which was directed by Rafael Arévalo Martínez and Francisco Fernandez. The magazine was their propaganda channel, and even though it was short lived -less than a year in 1913- it was the vehicle by which several new writers started their careers.

«Juan Chapín» Avenue

«Juan Chapín» avenue is located in zone 1 of Guatemala City, and was named to honor this particular character. It was built to improve the north side of the city, at a time when it was expanding exponentially to its south side. The idea was to connect in more direct way the transit coming from the Guarda of Gulf and Guarda of Chinautla city accesses and get to earn some equity for the neighboring land. Construction was done by jail prisoners and it was inaugurated on 11 November 1933, during general Jorge Ubico presidency.

See also

References

- Milla y Vidaurre 1875, p. I.

- ^ Milla y Vidaurre 1875.

- ^ Milla y Vidaurre 1865.

- ^ Johnston 1949, p. 449.

- Damisela n.d.

- Rodríguez Cerna 1933, p. 3.

Bibliography

- Damisela (n.d.). "Generación de 1910". Damisela blog spot (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 3 February 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: year (link) - Johnston, Marjorie C. (1949). "José Milla, retratista de costumbres guatemaltecas". Hispania (in Spanish). 32 (4). Phoenix, Arizona: American Association of Teachers of Spanish and Portuguese: 449–452. doi:10.2307/334402. JSTOR 334402.

- Milla y Vidaurre, José (1865). Cuadros de costumbres guatemaltecas (in Spanish). Guatemala: Imprenta de la Paz.

- Milla y Vidaurre, José (1875). Un viaje al otro mundo, pasando por otras partes. 1871 a 1874 (in Spanish). Guatemala: Imprenta del Comercio.

- Municipalidad de Guatemala (11 December 2009). "La avenida Juan chapín en la historia". muniguate.com (in Spanish). Guatemala. Archived from the original on 30 September 2014.

- Rodríguez Cerna, José (10 November 1933). "Inauguran avenida "Juan Chapín"". El liberal progresista (in Spanish). Guatemala. Archived from the original on 30 September 2014.

Notes

- Milla refers here to the 19th century.