Ethnic group

| |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| > 209,600 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| Jukun | |

| Religion | |

| Jukun Traditional Religion, Christianity, Islam | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Kuteb, Tarok, Atyap, Afizere, Eggon, Berom, Bajju, Ham, Kanuri, Koro, Adara, Idoma, Igala, Ebira, Nupe, Gbagyi, Efik, Tiv, Igbo, Yoruba, and other Benue-Congo peoples of Middle Belt and southern Nigeria |

Jukun (Njikum; Hausa: Kororofawa; Kanuri: Gwana, Kwana) are an ethno-linguistic group or ethnic nation in West Africa. The Jukun are traditionally located in Taraba, Benue, Nasarawa, Plateau, Adamawa, Bauchi and Gombe States in Nigeria and parts of northwestern Cameroon. They are descendants of the people of Kwararafa. Most of the tribes in the north central of Nigeria trace their origin to the Jukun people and are related in one way or the other to the Jukuns. Until the coming of both Christianity and Islam, the Jukun people were followers of their own traditional religions. Most of the tribes, Alago, Agatu, Rendere, Goemai in Shendam, and others left Kwararafa when it disintegrated as a result of a power tussle . The Jukuns are divided into two major groups; the Jukun Wanu and Jukun Wapa. The Jukun Wanu are fishermen residing along the banks of the river Benue and Niger where they run through Taraba State, Benue State and Nasarawa State. The Wukari Federation, headed by the Aku Uka of Wukari, is now the main centre of the Jukun people.

Ethnonyms

The term Jukun or Juku is derived from the Jukun compound word for 'men' or 'people', apa-juku. The Jukun of ,, Taraba State|Dampar]] and Wase, however, do not refer to themselves as Jukun but Wapa. They use the first part of the compound word apa-juku instead of the second. Their immediate neighbours refer to them by some form of this term. Thus the Kam call them Apang and the Chamba call them Kpazo.

The Jukun of Kona call themselves Jiba (/dʒibə/) but are called Kwana by their neighbours. They are known as Kpe by the Mumuye and Kwe by the Jen. The term Jukun is a generic term for all Jukun-speaking peoples.

The Hausa call them Kwararafa (Kororafa or Kororofa). The origin of the term has yet to be established but according to Hausa tradition, the name comes from the Hausa word for crawl, kololofa. This is because they believed the Jukun crawled into their country. The anthropologist C. K. Meek, however, suggests that it may have come from four possible origins:

- Kororofa may come from Kwana Apa, meaning the people of Kona.

- It may mean Kuru Apa, the king of the Jukun.

- It might have meant "the salt people" as the Kwararafa region was known for its salt-bearing qualities and was distributed all over the region. Both the Hausa and the Jukun knew it as kororo.

- Kororofa might mean "the river or water people", i.e. the Apa of the Kworra. The River Niger was called the Kworra by the Jukun, but the term was used for any river.

Benue river basin. The Jukun region is along the upper Benue River shaded dark green.

Benue river basin. The Jukun region is along the upper Benue River shaded dark green. An estimated approximation of the boundaries of the historical Kwararafa, the kingdom from which the modern Jukun claim descent.

An estimated approximation of the boundaries of the historical Kwararafa, the kingdom from which the modern Jukun claim descent.

Kwararafa was also applied to the Jukun state and its capital city. The Jukun people, however, did not know of this word hence did not use it. They called their ancient capital Api or Pi, or the compound Jukun term, Bie-Pi. This name means "the place of grass or leaves". Pi is a common Sudanic root meaning grass. Conversely, -pi is a common root for house or home and bie-pi can therefore mean town.

Population and demographics

Writing in the late 1920s, C. K. Meek estimated that there were approximately 25,000 Jukun-speakers then alive. Meek noted that the majority of the Jukun lived in scattered groups around the Benue basin, in an area that roughly corresponded to the extent of the kingdom of Kwararafa as it existed in the 18th century . That area of Jukun habitation, Meek noted, was bounded by Abinsi to the west, Kona to the east, Pindiga to the north and Donga to the south.

The language can be divided into six separate dialects: Wukari, Donga, Kona, Gwana and Pindiga, Jibu, and finally Wase Tofa, although Meek noted that the dialects of "Kona, Gwana and Pindiga differ so little that they may be regarded as one."

History

Origins

According to oral traditions of the Jukun people, their migration originated from the east, possibly from Yemen, located east of Mecca. They were led by a leader named Agadu and traveled through various places including Kordofan, Fitri, Mandara, and the Gongola area before reaching the Benue region. Anthropologist C.K. Meek documented another tradition that suggests the Jukun migrated alongside the Kanuri people from Yemen. They reportedly traveled through Wadai to Ngazargamu, the former capital of the Kanem-Bornu empire. They initially settled in the Lake Chad region but later moved to the Benue area due to conflicts with the Kanuri people and overpopulation around the lake. This tradition finds some support in a Bornu tradition, as reported by H.R. Palmer, which indicates that around 1250 A.D., the Kwona, a section of the Jukun, had established themselves along the Gongola River. However, the Hausa Bayajidda legend portrays Kororofa as one of the "illegitimate" children of Biram.

Kwararafa

The Jukun established a state that later developed into an empire centered around the Benue River, with its capital named Kororofa. The state was governed by a "Divine King" known as the Aku.

According to the Kano Chronicle, Yaji I, the eleventh Sarkin Kano and the first Muslim ruler of Kano, expanded his authority to the borders of Kororofa. The Chronicle mentions that upon Yaji's approach, the Jukun people fled Kororofa. Yaji remained in Kwararafa for a period of seven months. Kanajeji, Yaji's son and the thirteenth Sarkin Kano, reportedly received tribute in the form of two hundred slaves from the Kwararafa.During the reign of Muhammad Zaki, the twenty-seventh Sarkin Kano, Kwararafa launched an invasion of Kano, prompting the people of Kano to flee to Daura for safety. Kwararafa launched another attack on Kano in 1653, resulting in the destruction of Kofan Kawayi, one of the gates of Kano. Additionally, the Chronicle mentions that during the reign of Dadi, Kano faced further invasions. The Chronicle also records that during the reign of Dauda Zaria, under Queen Amina of Zazzau, conquered all the towns as far as Kwararafa and Nupe.

According to 'Katsina documents', there was a war between Kwarau, the Sarkin Katsina, and Kwararafa in 1260. The documents also mention that Katsina was invaded by Kwararafa sometime between 1670 and 1684. In Bornu, during the reign of Ali ibn al-Hajj Umar, the 49th Mai of Bornu from 1645 to 1684, Kwararafa attempted to invade Ngazargamu, the former capital of the Kanem-Bornu empire. However, their invasion was unsuccessful due to the fierce defense mounted by the people of Bornu, with assistance from some Tuaregs.

Kwararafa reached its height of power in the latter half of the seventeenth century. According to Sultan Muhammad Bello of the Sokoto Caliphate in the nineteenth century, Kwararafa was one of the seven greatest kingdoms of the Sudan. Sultan Bello even claimed that Kwararafa's influence extended to the Atlantic, although this assertion is likely an exaggeration. Historian J.M. Fremantle observed that Kwararafa had exerted its sovereignty over various regions at different times, including Kano, Bornu, Idoma, Igbira, and Igala.

However, towards the end of the eighteenth century, Kwararafa, like many states in the region, experienced a decline. The state later faced attacks from the Chamba and Fulani forces in the early nineteenth century, leading to its eventual collapse. Historian Tekena Tamuno suggests that factors such as the displacement of the slave trade by the palm oil trade in Calabar, coupled with internal instability, may have contributed to the decline of the Jukun-led Kwararafa state.

Modern history

As a result of the Fulani conquests at the beginning of the 19th century, the Jukun-speaking peoples became politically divided into various regional factions. By the 1920s, the main body of the Jukun population, known as the Wapâ, resided in and around Wukari, where they were governed by the local king and his administration. Other Jukun-speaking peoples living in the Benue basin, such as Jukun wanu of Abinsi, Awei District, Donga and Takum, remained politically separate from the Wukari government, and the Jukun-speakers in Adamawa Province recognised the governorship of the Fulani Emir of Muri.

In the post-colonial period, Nigeria has suffered violence, the result of multiple ethnic tensions among the different communities living in the country . Tensions exist between the Jukun and the neighbouring Tiv people, who migrated from Congo

Studies

In 1931, the academic publishing company Kegan Paul, Trubner & Co. published A Sudanese Kingdom: An Ethnographic Study of the Jukun-speaking Peoples of Nigeria, a book which had been written by the Briton C. K. Meek, the Anthropological Officer stationed with the Administrative Service in Nigeria.

List of Notable Jukun people

- Yakubu Alfred Samuila, Retired Customs Comptroller, Businessman and Public Policy Analyst.

- David Sabo Kente, businessman, politician and philanthropist

- Jesse Jagz, rapper, record producer and songwriter

- Kuvyon II, Aku Uka (paramount ruler) of Kwararafa

- M.I Abaga, hip hop recording artist and record producer

- Ezekiel Irmiya Afukonyo, politician, businessman and diplomat.

- Zinga Obadiah, Economist, Politician and businessman

- Theophilus Yakubu Danjuma, retired Nigerian army general, former Chief of Army Staff, former Minister of Defence, and businessman

References

Footnotes

- "Wapan Jukun in Nigeria".

- "Wanu Jukun in Nigeria".

- "Kona Jukun in Nigeria".

- "Wase Jukun in Nigeria".

- "Jukun | people | Britannica". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 26 December 2022.

- ^ Meek, Charles Kingsley (1969). A Sudanese kingdom; an ethnographical study of the Jukun-speaking peoples of Nigeria. Internet Archive. New York : Negro Universities Press. ISBN 978-0-8371-2430-8.

- Nwafor (12 March 2022). "PANKYA: The Horseman and His King". Vanguard News. Retrieved 27 December 2022.

- Owoicho, Ojobo. "Jukun people".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Abimbola O Adesoji and Akin Alao. "Indigeneship and Citizenship in Nigeria: Myth and Reality" (PDF). Obafemi Awolowo University. Retrieved 6 October 2010.

- ^ Meek 1931. p. 1.

- Meek 1931. pp. 1–2.

- ^ J.F. Ade. Ajayi and Ian Espie (1965). A Thousand Years of West African History. Internet Archive. Ibadan University Press.

- "Focus on central region Tiv, Jukun clashes". The New Humanitarian. 3 November 2015. Retrieved 27 December 2022.

- "Reasons why the Tiv and Jukun are in war | The Nation Newspaper". 29 June 2019. Retrieved 27 December 2022.

- Nwafor (3 November 2019). "How Gov Ishaku resolved Jukun, Tiv conflict". Vanguard News. Retrieved 27 December 2022.

- opinion (17 June 2020). "Implications of the Tiv-Jukun conflict in Taraba State". Businessday NG. Retrieved 27 December 2022.

- Meek 1931.

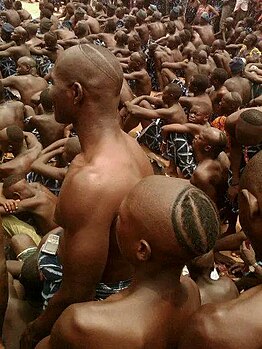

- "Ukenho: The sights and sounds of a Jukun carnival". Daily Trust. 22 December 2013. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

- Goldsmith, Melissa Ursula Dawn; Fonseca, Anthony J. (1 December 2018). Hip Hop around the World: An Encyclopedia [2 volumes]. ABC-CLIO. p. 377. ISBN 978-0-313-35759-6.

- "Anger over Ishaku's absence at Aku-Uka's burial". The Guardian Nigeria News - Nigeria and World News. 15 January 2022. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

- Idowu, Ronke Sanya (4 April 2022). "#TheIncredibles22: 6 Things You Should Know As MI Abaga Announces His Engagement".

- Ikpontu, Godson (11 June 2022). "2023 vice presidency: Spotlight on Ezekiel Afunkoyo - Blueprint Newspapers". Retrieved 28 June 2023.

Bibliography

- Meek, C. K. (1931). A Sudanese Kingdom: An Ethnographic Study of the Jukun-speaking Peoples of Nigeria. London: Kegan Paul, Trubner & Co.