| Jusuf Prazina | |

|---|---|

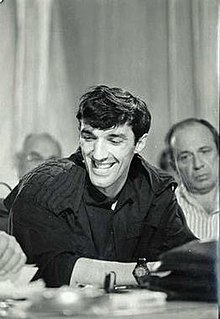

Jusuf Prazina in besieged Sarajevo, 1992 Jusuf Prazina in besieged Sarajevo, 1992 | |

| Nickname(s) | Juka |

| Born | (1962-09-07)7 September 1962 Sarajevo, PR Bosnia and Herzegovina, FPR Yugoslavia |

| Died | 4 December 1993(1993-12-04) (aged 31) Eupen, Belgium |

| Allegiance | |

| Service | Army of Bosnia and Herzegovina Croatian Defence Council |

| Years of service | 1992–1993 |

| Rank | General |

| Commands | Commander of Special Brigade ARBiH "Juka's Wolves" Head of Special Forces ARBiH Head of Special Forces HVO Member of General Staff ARBiH |

| Battles / wars | |

Jusuf "Juka" Prazina (pronounced [jǔsuf jûka prǎzina]; 7 September 1962 – 4 December 1993) was a Bosniak organized crime figure and warlord during the Bosnian War.

A troubled teen, Prazina's youth allegedly contained numerous stays in various jails and correctional facilities of the former Yugoslavia. By the 1980s, he had become involved in organized crime, eventually heading his own racketeering gang based around his home in the city's Centar municipality.

With the onset of the Siege of Sarajevo in 1992, Prazina expanded his gang into an effective paramilitary fighting force called Juka's Wolves. This force was central in the effort against the besieging Army of Republika Srpska (VRS), and he was rewarded for his contribution to the city's defense by appointment to the head of the government's special forces. Prazina proved problematic for the Army of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Following a warrant for his arrest in October, Prazina stationed himself on Mount Igman and coordinated attacks against the ARBiH until his eventual defeat and expulsion in January of the following year. Prazina moved to Herzegovina where he joined forces with the Croatian Defence Council and committed numerous crimes against civilians in the region. He left Bosnia and Herzegovina a few months later for Croatia, and lived on the Dalmatian coast before traveling through a number of European countries and finally relocating to Belgium.

He was found dead in a canal near the German border by two hitch-hikers on 31 December 1993. In 2001, documents detailing wartime conversations between then president of Croatia Franjo Tuđman and president of the Croatian parliament Stjepan Mesić were declassified. In one part of these documents, Mesić revealed his suspicions that Bosnian Croat extremists were to blame for Prazina’s death. The most concrete links came from an unsuccessful six-year investigation by the Bavarian Criminal Police.

Early life in Sarajevo

Prazina had two siblings: sister Vasvija and brother Mustafa. Growing up, he was known to his educators as a troublemaker and problematic student, spending time in a number of correctional facilities. It was also around this time that he became involved with a local gang on his home street of Sutjeska. As a teenager, he enrolled in a streamlined secondary school focusing on commerce, which perhaps contributed to his eventual involvement in racketeering. His early transgressions were limited to bullying and street brawls.

Shortly before the war, Prazina established and registered a debt collection business. His preferred methods, however, were mostly illegal. Prazina was known to first demand some form of authorization, then threaten a debtor and, if still receiving a negative response, use various forms of violence to force payment. In all this, Prazina developed a sophisticated network of around 300 armed "collectors" under his control.

He wielded great power through this enterprise: in early 1992, after being shot during a pit bull fight, doctors at Koševo hospital were hesitant to perform the necessary operation due to the great risk involved. In response, Prazina's small army besieged the hospital and forced the surgeons to attempt the job. Although a bullet remained (causing him to have a limp and reduced range of motion on his left hand for the rest of his life), Prazina ultimately survived and continued his activities. By the time the Yugoslav Wars were underway, Prazina had been arrested and jailed five times, and was a well-known figure in Sarajevo's underworld.

Siege of Sarajevo

See also: Siege of SarajevoRise to power

Following the start of the siege of Sarajevo, Prazina set out with his gang to defend the city from the attacks of the VRS (or "Chetniks," as he called them). Rapidly swelling his numbers, by May he was able to gather some 3,000 men outside the city's Druga Gimnazija high school (in the neighbourhood where he grew up on Sutjeska Street) and declare their intention to "defend Sarajevo." Juka's Wolves, as the group was called, were thoroughly armed with sawed-off shotguns and AK-47s (provided in part through a connection with the Croatian Defence Forces), and uniformed with crew-cuts, black jump-suits, sunglasses, basketball shoes, and sometimes balaclavas.

They were split into a number of locality-based factions, each under the direct control of one of Juka's close confidants but ultimately responsible to the central base ran by Prazina himself. In contrast to all this (and due to a variety of factors, including a pre-war policy that strove for a peaceful resolution and an international arms embargo), the central government under Alija Izetbegović and its formal army was relatively unorganized and unprepared. Because of this, the assistance of well-armed groups such as Prazina's private army in the city's defense was welcomed, and their pre-war criminality overlooked in light of their apparent willingness to fight for a united and sovereign Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Prazina played an integral role in defending Sarajevo during the early days of the siege. His forces cleared the streets of Serb paramilitaries and the areas under his control (most notably Alipašino polje) were considered impenetrable to the enemy. On a number of occasions he participated in actions orchestrated by the leaders of other military units more closely affiliated with the central government (such as Dragan Vikić), many of whom he had good relations with. He was proclaimed a hero by the Bosnian press while the Western media frequently portrayed him as a sort of Robin Hood figure. He was widely admired among the besieged Sarajevo populace, even appearing in contemporary patriotic songs. Prazina's own actions helped enhance the myth that was being built around him. At a time when many Sarajevans had to risk their lives for humanitarian food provisions, Prazina handed out candy to children on the street (albeit usually accompanied by the cameras of foreign news services). When Prazina captured a Serb sniper on the rooftop of a six-story building and accidentally caused the startled man to fall off the edge, the relatively uneventful story was transformed into a popular anecdote where Prazina personally threw one of the hated enemy sharpshooters to death.

Split with government

His popularity among Sarajevo citizens was in sharp contrast to the view held by central authorities. Despite his many positive contributions to the city's defense, Prazina's involvement had numerous negative aspects as well. He was ambitious and wanted to be named the overall head of the city's defense. He resented what he perceived to be the increasing involvement and influence of Bosniaks from Sandžak in the Bosnian army and government (the so-called Sandžak line), and in particular the power held by Sefer Halilović, the man who held his desired position (head of the general staff of ARBiH).

Prazina's frustrations were such that in late June he even laid siege to the Presidency Building, finally convincing the government that the issue had to be addressed immediately. He was soon after appointed to the General Staff of the ARBiH and made head of the army's special forces as well as commander of the Special Brigade of the ARBiH (i.e. the official term for his private army). Prazina was becoming more and more of a nuisance and the official titles essentially served as concessions to keep him at bay. Despite his appointment to the post, he was not considered to be an equal member of the General Staff, and tensions between him and Halilović worsened (on one occasion he broke into a press conference held by the General Staff and shouted "You, bastards! Why haven't I been invited?"). Prazina never abandoned his criminal past; he and his group were notoriously corrupt, involved in numerous grand thefts, in control of the city's black market, and increasingly connected to various atrocities against civilians and POWs.

His relations with central authorities steadily deteriorated over the course of the year. In September he had an allegedly threatening altercation with Alija Izetbegović in the president's office, following which he was asked to resign from his position as member of the General Staff. Increasingly troubled and unable to cope with Izetbegović's subtle plots to remove him from the center of power, his mental health reportedly further worsened when his pregnant wife Žaklina was wounded. After a short government-approved leave from the city to accompany his wife for medical treatment, he returned to Sarajevo and continued to conduct his forces more and more independently of the government. In October the Bosnian government finally issued a warrant for Juka's arrest, accusing him of treason, extortion, and an addiction to cocaine. He was briefly arrested during a stop in Konjic, but freed as soon as a group of his followers gathered outside the police station and demanded he be released.

Escape to Igman

No longer safe in Sarajevo, Prazina decided to establish himself on Mt. Igman above the city. His announced intentions were to come down from the mountains, break the siege of the city, and overthrow his enemies in the central government. In a December interview with the CBC, he stated that the required action was imminent because he wanted the victory to be a present to Sarajevans for Christmas. However, his former officers who remained entrenched in the city below refused to answer his calls for them to join him. Not willing to leave their defensive positions and open up various fronts for the VRS, the greater part of Prazina's former army remained in the city and was formally incorporated into the ARBiH. This left Prazina with only around 200 of his most loyal followers on Igman. That fall and winter saw numerous battles between Prazina and ARBiH forces on the mountain.

The decisive altercation occurred one day when Prazina expected to initiate a counter-offensive against certain government units with another local warlord, Zulfikar "Zuka" Ališpago. Unbeknownst to Prazina, Ališpago was working for the ARBiH, which had even supplied him with six tanks for a final confrontation with Prazina. Ališpago tricked Prazina into sending over his troops under the pretense of helping with preparations for the offensive. When Prazina's men arrived at Ališpago's base, they were either captured or executed. By the time Prazina realized he was facing a trap, it was too late. Ališpago's forces initiated an offensive and Prazina was forced to retreat and flee Mt. Igman.

Activities in Herzegovina

During his time on Mt. Igman, Prazina had established formal ties with the HVO through Bosnian Croat warlord Mladen "Tuta" Naletilić and, following the Bosnian government's decision to relieve him of his ARBiH commands, aligned himself with Naletilić's "Convicts Battalion" paramilitary unit. Not content with this state of affairs and wishing to fight under a recognized army, Prazina asked to be formally incorporated into the HVO on 14 December. Initially the HVO denied his request by stating that they had nothing to gain from having a presence on Igman, but by the latter half of his stay on the mountain his eventual transfer to the HVO was considered imminent. In trying to convince his closest officers to join him on Igman he had revealed his intentions of joining the HVO and their willingness to accept him; revelations which played a role in their refusal to follow him. Despite this lack of support from his former comrades, the consequences of his defeat at the hands of Zuka and the ARBiH made HVO held territory in Herzegovina a logical destination for Prazina.

The HVO authorities appointed Prazina head of their Special Forces and assigned him to guard over the Sarajevo-Mostar corridor near the hydroelectric power plant Salakovac in northern Herzegovina. There he routinely stopped and maltreated passing Bosniaks; particularly those that hailed from Sarajevo or Sandžak. Following the start of the Bosniak-Croat conflict that spring, the HVO launched a major offensive in Mostar on 9 May 1993. Prior to the conflict, the population of Mostar (the major urban center of Herzegovina) was nearly evenly split among the two peoples. With the battle front running down the city's main boulevard, the HVO set out to ethnically cleanse the western side of town under their control. Prazina and his unit, sent down from their previous post, were responsible for carrying out the bulk of this operation.

Prazina justified his actions by branding the expelled Bosniak civilians as extremists, and by claiming that their homes in the tower blocks had to be vacated so as to not leave good vantage points for enemy snipers. For the remainder of his stay in Herzegovina, Prazina fought against ARBiH forces on a portion of the front line along the boulevard. He also reportedly ran the Heliodrom Camp for Bosniaks, making frequent visits and even directly participating in the maltreatment of detainees.

Later days and death

Following his actions in Herzegovina Prazina left for Croatia, spending several months in a villa on the Dalmatian coast provided for by the Croatian government. General Stjepan Šiber would later recount to Sarajevo media a brief encounter he had with him in a Zagreb hotel lobby in early May 1993. He stated that Prazina approached him, expressed regret for his actions and asked to be forgiven and reinstated to the ARBiH. Šiber assured Prazina he would do what he could, after which the two never saw each other again. Not allowed to carry weapons by the Zagreb authorities, Prazina allegedly grew bitter and restless.

Through bribes and threats, he eventually managed to get a permission to go to Slovenia for himself and twenty close companions. From there the group moved through Austria and Germany before finally relocating to Liège, Belgium. Although Prazina settled himself and his followers in a neighborhood populated mostly by immigrants from Turkey and the Maghreb, he eventually established himself among the city's small Yugoslav emigrant community. There, Prazina was last seen the night of 3 December 1993. He went out with his bodyguards after a game of cards and never came back. The next morning, German police found his Audi abandoned at the railroad station in Aachen. The car body had two bullet holes from a 9 mm handgun; presumed to be a Beretta. Prazina's body was discovered in a canal alongside a highway near the German border by two Romanian hitch-hikers on New Year's Eve. The bullets found in Prazina's head corresponded to the holes in his car, and the ownership of a Beretta by one of his bodyguards sealed the case in the eyes of Belgian police. The four bodyguards were arrested, and three of them went on to be tried and sentenced to serve time in prison.

As the specific motive was never established, the case allowed for numerous conspiracy theories. Croatian media at the time blamed the Bosnian government of Alija Izetbegović and claimed there were links to the Syrian secret service. In 2001, documents detailing war-time conversations between then president of Croatia Franjo Tuđman and president of the Croatian parliament Stjepan Mesić were declassified. In one part of these documents, Mesić revealed his suspicions that Bosnian Croat extremists were to blame for Prazina's death. The most concrete links came from an unsuccessful six-year investigation by the Bavarian Criminal Police. The investigation implicated Bosniak gangster Senad "Šaja" Šahinpašić, and was based on tapped phone conversations which showed that Šahinpašić was aware of Prazina's death by 5 December 1993 – well before his body had been discovered. Šahinpašić had previously been involved in threatening altercations with Prazina, who had considered Šahinpašić to be a threat due to his financial resources and Sandžak origins. Witness testimonies and the nature of the questions asked by investigators showed that the German police had serious indications that Prazina had been killed by Zijo Oručević from Mostar. Specifically, one witness testified that he believed Šahinpašić had convinced Oručević to issue an order for the assassination of Prazina. Deciding that there was not enough evidence for a prosecution, the police closed the investigation on 15 December 1998.

Legacy

Collaboration with VRS

Throughout his time in Sarajevo, Prazina collaborated with Republika Srpska officials in a variety of criminal activities. He often exchanged money, people, and prisoners of war with VRS authorities in the occupied territories around Sarajevo. With their support, Prazina was able to effectively run the black market during the siege. In his dealings with the VRS, Prazina even had written permission from the president of the Republika Srpska, Radovan Karadžić. During the siege, Prazina was also in contact with Radovan's son, Saša. Post-war revelations of these activities have served to sour Prazina's legacy among the Bosniak citizens of Sarajevo, who once considered him among the most positive figures of the Bosnian war.

War crimes in Sarajevo

Prazina was accused of committing various war crimes over the course of the war. An order from president Izetbegović placed Prazina beyond the control of the military police, and his men were known to take prisoners of war from government prisons for their own purposes. Many regular residents of Sarajevo were also treated harshly; members of his unit were involved in extortion, looting and rape, as well as various instances of violence against civilians. In one case, while on Mt. Igman, Prazina personally beat one fleeing civilian's head against the hood of a car. Within the city, Prazina's Wolves were known for appropriating apartments and abducting and abusing their owners. Furthermore, as part of black market activities, Prazina's unit frequently raided the city's shops and warehouses.

See also

References

- ^ Selimbegović, Vildana. "Osuđen na smrt" Archived 2006-05-27 at the Wayback Machine, Dani, No. 262, bhdani.com, 21 June 2002.

- ^ Selimbegović, Vildana. "Bacio je samo jednog snajperistu Archived 2006-09-27 at the Wayback Machine." Dani, No. 259. 31 May 2002.

- ^ Vreme (1994-01-10). "Juka of Sarajevo". Archived from the original on 12 May 2008. Retrieved 2024-08-11.

- ^ Secretary-General, Un (31 May 1995). "Annex III.A "Special Forces"". Annexes to the final report of the Commission of Experts Established pursuant to Security Council Resolution 780 (1992). Vol. 1. Annexes 1 to 5. United Nations Digital Library. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- ^ Selimbegović, Vildana. "Kako je pjevao četnicima" Archived 2010-03-13 at the Wayback Machine, Dani, No. 260, 7 June 2002.

- ^ Selimbegović, Vildana. "Volio bih da sam ga slikao u Zagrebu" Archived 2006-05-12 at the Wayback Machine, Dani, No. 261, 14 June 2002.

- ^ "Main News Summary". SFOR. 9 July 2004.

- ^ Halilović, Semir (2005). Državna tajna. Matidca d.o.o. Sarajevo. ISBN 9958-763-05-2.

- 1962 births

- 1993 deaths

- Military personnel from Sarajevo

- Bosniaks of Bosnia and Herzegovina

- Bosnia and Herzegovina Muslims

- Bosnia and Herzegovina gangsters

- Military personnel of the Bosnian War

- Army of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina soldiers

- Deaths by firearm in Bosnia and Herzegovina

- Murdered gangsters

- Bosnia and Herzegovina people murdered abroad

- Croatian Defence Council soldiers

- War criminals