| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Edmund de Unger" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (January 2021) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

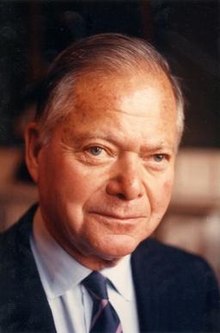

Edmund Robert Anthony de Unger (Hungarian: Ödön Antal Robert de Unger, 6 August 1918, Budapest – 25 January 2011, Ham, London, UK) was a Hungarian-born property developer and art collector. In London he built up the Keir Collection, one of the greatest post-war collections of Islamic art, bequeathed in 2008 to the Pergamon Museum of Islamic Art in Berlin. The arrangement for the museum to curate the collection came to an end in July 2012. The collection is now hosted by the Dallas Museum of Art as of May 2014 for a 15-year renewable loan.

Life

Edmund de Unger was born in Budapest into a family linked with the art world. His father was a private collector of carpets and another relative was the architect who designed the Hungarian National Museum. After going to London in 1934 to learn English, he studied economics at Kiel Institute for the World Economy, law at the University of Budapest and history at Hertford College, Oxford. Returning to Hungary before the outbreak of World War II, in 1945 he married Eva Spicht, one of 22 Jewish refugees whom he had taken in during the Battle of Budapest. After the war he restored and ran the Astoria Hotel in Budapest, until it was requisitioned by the communist regime in 1948.

In 1949 de Unger, following a series of arrests in Hungary, moved permanently to England, working first as a manservant. After further training, he entered the legal profession as a barrister. He later worked as Crown Counsel in Ghana for the Colonial Office. The period in West Africa permitted visits to Egypt, where he developed an interest in Coptic and Islamic art. On returning to England, de Unger became a property developer, which provided him with the means to build up his post-war art collection, which he named the "Keir Collection", after one of his first homes The Keir on Wimbledon Common in London. In 1965, following the death of his first wife Eva in 1959, he married Elizabeth Allen, with whom he had two sons, Richard and Glen.

The ever-increasing Keir Collection was moved in the late 1960s to his house in Ham, Surrey. The collection, which started in his youth with carpets, gradually grew to include ceramics, in particular rare items of lustreware from Mesopotamia, Persian and Moghul miniatures, medieval and Renaissance enamels, sculptures, and textiles from Italy and France (including the medieval enamels collection of Ernst and Martha Kofler-Truniger). Widely knowledgeable on the area in which he collected, de Unger founded the Islamic Art Circle in 1964 and lectured frequently on his expertise all over the world.

Keir Collection

Carpets and textiles

"My love of Islamic art began with carpets. I first became aware of them at the age of six, when my father Richard told me not to walk on them. My father was a rather solitary person and, seeing my interest, he must have been pleased. He took me to museums, and by the age of nine I was quite a good companion to him in the salesrooms. After the war and my departure from my homeland I was once again able to continue the collecting of what my fellow Oxford undergraduates had called "moth-eaten rags". Slowly, not only the floors but also the walls of my home became covered with new acquisitions."

The majority of carpets that form the core of the Keir Collection remain in the 18th century Manor House on Ham Street in Richmond, London, which was de Unger's home up to his death in 2011. A small but representative portion of classical oriental carpets from Persia, Turkey and Mughal India are on display in the Pergamon Museum of Islamic Art.

His passion for collecting carpets soon led de Unger to diversify into fine textiles, starting in 1961 with the acquisition of Persian embroidery in Paris. He started collecting decorative silk, velvet and brocade fabrics, with elaborate designs resembling those in the carpets. There provenance included the Persian, Ottoman and Mughal empires, with Safavid silks forming the nucleus of his collection. It incorporates parts of the older textile collections of Joseph V. McMullan and Hagop Kevorkian. With Werner Abegg as mentor de Unger moved on to mediaeval and Renaissance woven cloth from Europe, particularly Italy and Spain, and in number these items dominate the collection.

-

6th-8th century Coptic wall hanging or carpet, decorated with flowers, human faces and heraldic eagles

6th-8th century Coptic wall hanging or carpet, decorated with flowers, human faces and heraldic eagles

-

Fragment of 12C-13C Spanish or Italian silk decorated with animals of prey and palmettes

Fragment of 12C-13C Spanish or Italian silk decorated with animals of prey and palmettes

-

Late 15th century Italian silk velvet panel, with phoenix and plant motifs, from Keir Collection, now in Victoria and Albert Museum

Late 15th century Italian silk velvet panel, with phoenix and plant motifs, from Keir Collection, now in Victoria and Albert Museum

-

17th century Safavid carpet from Azerbaijan

17th century Safavid carpet from Azerbaijan

-

Polonaise Carpet. Iran, 17th century

Polonaise Carpet. Iran, 17th century

-

17th century Turkish carpet from Kula in the private collection of the de Unger family

-

"Cartouche and Tree" Carpet. Khorasan, c. 1700

"Cartouche and Tree" Carpet. Khorasan, c. 1700

Ceramics

"The end came when I observed every carpet on the floor was covered by at least two other layers. I realized it could not go on. It was at that moment that I had my first encounter with Islamic ceramics. Just like their woven counterparts these have the same combination of warmth of colour, delicacy and boldness of design. Above all, I admire the lustre ware which to my mind is the greatest gift the Islamic potter has made to mankind."

De Unger's extensive collection of Islamic ceramics contains important examples from the mediaeval period, from the 8th to the 13th century. Some of the most prized items are of gold lustreware, a technique that originated and was perfected in Iraq. These skills were passed on to artisans in Fatimid Egypt and Kashan in Persia. The Persian lustreware tiles provide examples of figurative representations in Islamic art prior to the Mongol period.

-

Fatimid Luster Plate with Cock Fight. Cairo, 11th-12th century

Fatimid Luster Plate with Cock Fight. Cairo, 11th-12th century

-

Figurine of a Seated Lioness. 12th-13th century

Figurine of a Seated Lioness. 12th-13th century

-

Early 13C vertical-format Persian tile from Kashan, with a bearded man and 15 women, each with nimbus and diadem

Early 13C vertical-format Persian tile from Kashan, with a bearded man and 15 women, each with nimbus and diadem

-

Tile, fritware with underglaze painting. 17th century

Tile, fritware with underglaze painting. 17th century

Rock crystal

Rock crystal artefacts flourished during the Fatimid period in Egypt (969-1171). Because of the difficulty of working with the very hard medium, only the caliph and his immediate court could afford these objets d'art, which varied in size from small animal forms to large vessels. In 1068, however, the large collection of treasures in the Caliph's palace in al-Qahira (now part of modern-day Cairo) was dispersed throughout the medieval world as the result of a revolt by the unpaid army. Very few items from the reportedly large collection survive. Several of these rare sculpted rock crystals came to form parts of reliquaries in Medieval church treasuries, in mountings made for gold and precious stones. De Unger acquired several rock crystal pieces from this period for his collection including a fine vessel decorated with palmettes, set in an elaborate gold casing with handles formed of foliage and winged dragons. Other smaller items in the collection include several bottles, possibly intended for dispensing scent, and a bead in the form of a crouching hare, possibly intended as a charm.

In October 2008, an 11th-century Fatimid rock crystal ewer was acquired for the Keir Collection at a public auction in Christie's by de Unger's son, Richard, for over £3 million. Set in a medieval Italian gold and enamel mount, the ewer had earlier in the year been offered for auction in Somerset as a nineteenth-century French claret decanter with an estimated price of between £100 and £200. Islamic art experts present at the auction recognized the rarity of the artifact, which sold for just over £200,000. Subsequently, the owner withdrew the object from sale, placing it for auction at Christie's, who gave an evaluation with a starting price of £3 million, expecting a higher price, despite the 2007–2008 financial crisis. When de Unger requested an export order so that the ewer could go on display in Berlin, the UK government sought its own evaluation from Sotheby's, who returned a figure of £20 million, beyond the means of any public British art collection. With a change of government, Sotheby's figure was accepted and the ewer, one of only a very small number of surviving rock glass vessels of this type, is now on display in the Pergamon Museum of Islamic Art.

Islamic art of the book

"As a child, one of my favourite books was the Arabian Nights, and its colourful descriptions and rich imaginative quality must have left a mark on me. The first Oriental miniature I consciously looked at was at the Musée d'Arts décoratifs in Paris It was this painting that prompted me to buy my first book on Persian miniatures."

As Haase (2007) stated at the start of his evaluation of de Unger's extensive collection of Islamic illuminated manuscripts, "A series of magnificent exhibitions of Islamic manuscript art and calligraphy has recently shown splendid masterpieces from several regions of the Orient and revealed the stereotype of Islam's hostility towards illustration and the "substitute art" of calligraphy as nothing more than absurd." The collection of de Unger, although containing many examples of medieval calligraphy, particularly Korans, has an even larger number of illuminated figurative manuscripts.

The calligraphic manuscripts in the Keir Collection were produced by some of the most accomplished artists of the period from across the entire Islamic world. With intricate designs in luxurious gold and blue or polychrome, these date from the twelfth to the fifteenth century and originate from Syria, Spain, North Africa (particularly Mamluk Egypt), Iraq, Iran and India.

The miniature paintings on detached folios, which form the bulk of de Unger's collection, contain illustrations of Persian epic poems, including the celebrated Shahnameh, the "Book of Kings", of Firdausi and the Khamsa of Nizami. The figurative illuminated manuscripts cover the period from the early 14th century to the early 17th century and again range across the whole Islamic world, from Turkey to Mughal India.

In addition to folios from illuminated manuscripts, de Unger collected examples of Islamic bookbinding, one of the most highly developed skills in the Islamic world. His collection includes Persian leather bindings, some polychromatic, embossed with highly ornamental designs in gold. There are also examples of bookbindings with flap, some with elaborate miniature lacquerwork painting either on leather or on a papier-mâché base.

-

Double page from the Qur'an manuscript made for Nur ad-Din and endowed to his madrasa in Damascus in 652 AH/1166–7 AD

Double page from the Qur'an manuscript made for Nur ad-Din and endowed to his madrasa in Damascus in 652 AH/1166–7 AD

-

Luxury Quran, ca 1300, with gold leaf calligraphy from Andalusia or Morocco

Luxury Quran, ca 1300, with gold leaf calligraphy from Andalusia or Morocco

-

Firman of Muhammad bin Tughluq dated Shawwal 725 AH/September-October 1325

Firman of Muhammad bin Tughluq dated Shawwal 725 AH/September-October 1325

-

Iskandar and His Men Killing a Dragon in the Mountains, Folio from the Great Mongol Shahnameh. Tabriz, c. 1330

Iskandar and His Men Killing a Dragon in the Mountains, Folio from the Great Mongol Shahnameh. Tabriz, c. 1330

-

A ruler receives an envoy - left half of the double page frontispiece from the "Big Head" Shahnameh. Lahijan, 1494

A ruler receives an envoy - left half of the double page frontispiece from the "Big Head" Shahnameh. Lahijan, 1494

-

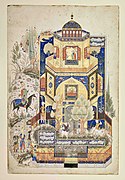

Khusraw at Shirin’s Palace, Folio from the Khamsa of Nizami. Tabriz, last quarter of the 15th-century

Khusraw at Shirin’s Palace, Folio from the Khamsa of Nizami. Tabriz, last quarter of the 15th-century

-

Bizhan slaughters the wild boars of Irman, Miniature from the Shahnameh of Shah Tahmasp. Tabriz, c. 1530

Bizhan slaughters the wild boars of Irman, Miniature from the Shahnameh of Shah Tahmasp. Tabriz, c. 1530

-

17th century Mogul miniature of an old courtier from the reign of Jahangir

17th century Mogul miniature of an old courtier from the reign of Jahangir

Metalwork

"I believe that no collection of Islamic art can be complete without metalwork It tells us a great deal about the art of Islam, the inscriptions found on the metalware contributing significantly to the history of the subject. I recognize in Islamic metalwork that intrinsic quality which is the result of first-class workmanship."

The creation of finely wrought metalware, in gold, silver and copper alloys, was from the outset one of the most highly developed skills in Islamic art. The artefacts were produced for the whole range of society from the courtly elite to the merchant class. The Keir Collection reflects this diversity. Amongst the most precious objects are enamel and gold jewelry and engraved silverware; other household objects include engraved bronze ewers, jugs, perfume bottles, aquamaniles, incense burners and candlesticks from all over the Islamic world, from the 8th to the 16th century.

-

Reclining Bronze Buffalo. 11th-13th century

Reclining Bronze Buffalo. 11th-13th century

-

Display Dish with Pairs of Musicians in Medallions. Iran, 13th-century

Display Dish with Pairs of Musicians in Medallions. Iran, 13th-century

-

Casket. Iran, second half of the 14th-century

Casket. Iran, second half of the 14th-century

Medieval enamels

The collection of medieval and Renaissance enamels of Ernst and Martha Kofler-Truninger was purchased by de Unger in two parts in 1970 and 1971. It remained in the Keir Collection until 1997, when the bulk of the collection was auctioned at Sotheby's with a pre-sale estimate of $25 million that was not realised, with some items remaining unsold or withdrawn.

-

Late 12th century Limoges enamel plaque of angels with censers from Keir Collection, now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Late 12th century Limoges enamel plaque of angels with censers from Keir Collection, now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Late 13th century French gilded and enamelled copper disc from Keir Collection, now in British Museum

Late 13th century French gilded and enamelled copper disc from Keir Collection, now in British Museum

-

14th century Spanish plaque for altar cross from Keir Collection, now in British Museum

14th century Spanish plaque for altar cross from Keir Collection, now in British Museum

-

13th century French incense boat, champlevé enamel on copper with gilding, now in the Walters Art Museum

13th century French incense boat, champlevé enamel on copper with gilding, now in the Walters Art Museum

Notes

- Museum für Islamische Kunst (13 July 2012). "Die Keir Collection verlässt Berlin".

- See Obituary (2011) and Grimes (2011)

- Haase 2007, p. 7

- Haase 2007, pp. 98–105

- Haase 2007, pp. 80–97

- Haase 2007, p. 7

- Haase 2007, pp. 70–79

- Haase 2007, pp. 64–69

- See Crane (2008) and Bailey (2010)

- Haase 2007, p. 8

- Haase 2007, pp. 14–55

- Haase 2007, pp. 56–63

- Haase 2007, p. 8

- Haase 2007, pp. 106–129

- Obituary 2011

References

- Haase, Claus-Peter (2007), A Collector's Fortune: Islamic Art from the Collection of Edmund de Unger, Hirmer Publishers, ISBN 978-3-7774-4085-9, distributed by University of Chicago Press

- Robinson, B. W. (1988), Islamic Art in the Keir Collection, London: Faber and Faber, ISBN 0-571-13753-9

- Fehérvári, Géza (1976), Islamic Metalwork of the Eighth to the Fifteenth Century in the Keir Collection, Faber and Faber, ISBN 0-571-09740-5

- Grube, Ernst J. (1976), Islamic Pottery of the Eighth to the Fifteenth Century in the Keir Collection, Faber and Faber, ISBN 0-571-09953-X

- Robinson, B. W. (1976), Islamic Painting and the arts of the book, Faber and Faber, ISBN 0-571-10866-0

- Carswell, John (2008), "Edmund de Unger. Prime Collector", Hali – Carpet, Textile & Islamic Art, 156, London: Hali Publications, ISSN 0142-0798

- Spuhler, Friedrich (1978), Islamic carpets and textiles in the Keir Collection, Faber and Faber, ISBN 0-571-09783-9

- Obituary (15 February 2011), "Edmund de Unger", The Daily Telegraph

- Grimes, William (20 February 2011), "Edmund de Unger, Islamic Art Collector, Is Dead at 92", The New York Times

- Crane, Anne (2008), "Fatimid rock crystal ewer acquired for the Keir Collection for £2.8 million at Christie's", Antiques Trade Gazette

- Bailey, Martin (2010), ""Overvalued" ewer exported", The Art Newspaper

External links

- A Collector's Fortune. Islamic Art Masterpieces of the Keir Collection, Pergamon Museum of Islamic Art

- Photograph of a 12th-century Fatimid bronze lion aquamanile with spout, Pergamon Museum of Islamic Art

- Images of artefacts from the Keir Collection:

- Fatimid rock crystal bead in form of hare

- Early 11th century Fatimid rock crystal oval bottle

- 13th century Homberg brass and silver ewer from Northern Iraq

- 13th century gold, silver and brass part of window grille from Western Iran

- Early 13th century silver bowl from Western Iran

- Early 9th century bronze ewer, decorated with dolphins, hares and palmettes, from Iraq

- Video showing details of three Fatimid rock crystal ewers on display in the Pergamon Museum of Islamic Art

- Object is light and stone, article in German on the Fatimid rock crystal ewer, Museumsjournal 2011, Stefan Weber, director of Pergamon Museum of Islamic Art.

- Early 20th-century views of the entrance and garden of the Manor House in Ham, Surrey (a grade II* listed building), from the English Heritage Archive

- Report on auction of Medieval artefacts in the Keir Collection, The New York Times, 1997.

- Second report on auction, The New York Times, 1997.

- The Virgin of the Battles, one of the medieval Limoges sculptures from the Keir Collection auctioned in 1997, now in Museo de Burgos

- The Madrid Chasse, one of the Medieval artefacts from the Keir collection auctioned in 1997, now in the Art Gallery of Ontario