| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Lesch–Nyhan syndrome" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (February 2022) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

| Lesch–Nyhan syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Juvenile gout, Primary hyperuricemia syndrome, Choreoathetosis self-mutilation syndrome, X-linked primary hyperuricemia, HGPRT deficiency |

| |

| A boy with Lesch–Nyhan syndrome wearing arm restraints | |

| Specialty | Endocrinology |

| Symptoms | self harm, dystonia, chorea, spasticity, intellectual disability, hyperuricemia, |

| Complications | kidney failure, megaloblastic anemia |

| Differential diagnosis | cerebral palsy, dystonia, Familial dysautonomia |

| Frequency | 1 in 380,000 |

Lesch–Nyhan syndrome (LNS) is a rare inherited disorder caused by a deficiency of the enzyme hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferase (HGPRT). This deficiency occurs due to mutations in the HPRT1 gene located on the X chromosome. LNS affects about 1 in 380,000 live births. The disorder was first recognized and clinically characterized by American medical student Michael Lesch and his mentor, pediatrician William Nyhan, at Johns Hopkins.

The HGPRT deficiency causes a build-up of uric acid in all body fluids. The combination of increased synthesis and decreased utilization of purines leads to high levels of uric acid production. This results in both high levels of uric acid in the blood and urine, associated with severe gout and kidney problems. Neurological signs include poor muscle control and moderate intellectual disability. These complications usually appear in the first year of life. Beginning in the second year of life, a particularly striking feature of LNS is self-mutilating behaviors, characterized by lip and finger biting. Neurological symptoms include facial grimacing, involuntary writhing, and repetitive movements of the arms and legs similar to those seen in Huntington's disease. The cause of the neurological abnormalities remains unknown. Because a lack of HGPRT causes the body to poorly utilize vitamin B12, some males may develop megaloblastic anemia.

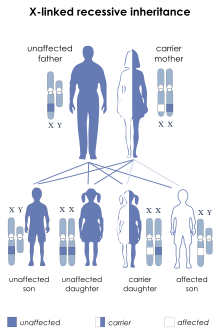

LNS is inherited in an X-linked recessive manner; the gene mutation is usually carried by the mother and passed on to her son, although one-third of all cases arise de novo (from new mutations) and do not have a family history. LNS is present at birth in baby boys. Most, but not all, persons with this deficiency have severe mental and physical problems throughout life. Cases in females are very rare.

The symptoms caused by the buildup of uric acid (gout and kidney symptoms) respond well to treatment with medications such as allopurinol that reduce the levels of uric acid in the blood. The mental deficits and self-mutilating behavior do not respond well to treatment. There is no cure, but many affected people live to adulthood. Several new experimental treatments may alleviate symptoms.

Signs and symptoms

LNS is characterized by three major hallmarks: neurologic dysfunction, cognitive and behavioral disturbances including self-mutilation, and uric acid overproduction (hyperuricemia). Damage to the basal ganglia causes affected individuals to adopt a characteristic fencing stance due to the nature of the lesion. Some may also have macrocytic anemia due to the faulty DNA synthesis, most likely due to deficient purine synthesis that leads to a lag of cell division with respect to increases in cell mass. Virtually all patients are male; males experience delayed growth and puberty, and most develop shrunken testicles or testicular atrophy. Female carriers are at an increased risk for gouty arthritis but are usually otherwise unaffected.

Overproduction of uric acid

One of the first symptoms of the disease is the presence of sand-like crystals of uric acid in the diapers of the affected infant. Overproduction of uric acid may lead to the development of uric acid crystals or stones in the kidneys, ureters, or bladder. Such crystals deposited in joints later in the disease may produce gout-like arthritis, with swelling and tenderness. The overproduction of uric acid is present at birth, but may not be recognized by routine clinical laboratory testing methods. The serum uric acid concentration is often normal, as the excess purines are promptly eliminated in the urine. The crystals usually appear as an orange grainy material, or they may coalesce to form either multiple tiny stones or distinct large stones that are difficult to pass. The stones, or calculi, usually cause hematuria (blood in the urine) and increase the risk of urinary tract infection. Some affected people have kidney damage due to such kidney stones. Stones may be the presenting feature of the disease, but can go undetected for months or even years.

Nervous system impairment

The periods before and surrounding birth are typically normal in individuals with LNS. The most common presenting features are abnormally decreased muscle tone (hypotonia) and developmental delay, which are evident by three to six months of age. Affected individuals are late in sitting up, while most never crawl or walk.

Irritability is most often noticed along with the first signs of nervous system impairment. Within the first few years of life, extrapyramidal involvement causes abnormal involuntary muscle contractions such as loss of motor control (dystonia), writhing motions (choreoathetosis), and arching of the spine (opisthotonus). Signs of pyramidal system involvement, including spasticity, overactive reflexes (hyperreflexia) and extensor plantar reflexes, also occur. The resemblance to athetoid cerebral palsy is apparent in the neurologic aspects of LNS. As a result, most individuals are initially diagnosed as having cerebral palsy. The motor disability is so extensive that most individuals never walk, and become lifelong wheelchair users.

Self-injuring behavior

Persons affected are cognitively impaired and have behavioral disturbances that emerge between two and three years of age. The uncontrollable self-injury associated with LNS also usually begins at three years of age. The self-injury begins with biting of the lips and tongue; as the disease progresses, affected individuals frequently develop finger biting and headbanging. The self-injury can increase during times of stress. Self-harm is a distinguishing characteristic of the disease and is apparent in 85% of affected males.

The majority of individuals are cognitively impaired, which is sometimes difficult to distinguish from other symptoms because of the behavioral disturbances and motor deficits associated with the syndrome. In many ways, the behaviors may be seen as a psychological extension of the compulsion to cause self-injury, and include rejecting desired treats or travel, repaying kindness with coldness or rage, failing to answer test questions correctly despite study and a desire to succeed, and provoking anger from caregivers when affection is desired.

Compulsive behaviors also occur, including aggressiveness, vomiting, spitting, and coprolalia (involuntary swearing). The development of this type of behavior is sometimes seen within the first year, or in early childhood, but others may not develop it until later in life.

LNS in females

While carrier females are generally an asymptomatic condition, they do experience an increase in uric acid excretion, and some may develop symptoms of hyperuricemia, and experience gout in their later years. Testing in this context has no clinical consequence, but it may reveal the possibility of transmitting the trait to male children. Women may also require testing if a male child develops LNS. In this instance, a negative test means the son's disease is the result of a new mutation, and the risk in siblings is not increased.

Females who carry one copy of the defective gene are carriers with a 50% chance of passing the disease on to their sons. In order for a female to be affected, she would need to have two copies of the mutated gene, one of which would be inherited from her father. Males affected with LNS do not usually have children due to the debilitating effects of the disease. It is possible for a female to inherit an X chromosome from her unaffected father, who carries a new mutation of the HGPRT gene. Under these circumstances, a girl could be born with LNS, and though there are a few reports of this happening, it is very rare. The overwhelming majority of patients with LNS are male.

Less severe forms

A less severe, related disease, partial HPRT deficiency, is known as Kelley–Seegmiller syndrome (Lesch–Nyhan syndrome involves total HPRT deficiency). Symptoms generally involve less neurological involvement but the disease still causes gout and kidney stones.

Genetics

LNS is due to mutations in the HPRT1 gene, so named because it codes for the enzyme hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferase (HPRT or HGPRT, EC 2.4.2.8). This enzyme is involved in the biochemical pathways the body uses to produce purines, one of the components of DNA and RNA. Defects of this enzyme lead to increased production of uric acid. Since the HPRT gene is located on the X chromosome, LNS is an X-linked inherited disease.

The father of an affected male will not be the carrier of the mutant allele, and will not have the disease. An obligate carrier would be a woman who has an affected son and one other affected relative in the maternal line.

If a woman is the first in her family with an affected son, Haldane's rule predicts a 2/3 chance that she is a carrier and a 1/3 chance that the son has a new germline mutation.

The risk to siblings of an affected individual depends upon the carrier status of the mother herself. A 50% chance is given to any female who is a carrier to transmit the HPRT1 mutation in each pregnancy. Sons who inherit the mutation will be affected while daughters who inherit the mutation are carriers. Therefore, with each pregnancy, a carrier female has a 25% chance of having a male that is affected, a 25% chance of having a female that is a carrier, and a 50% chance of having a normal male or female.

Males with LNS generally do not reproduce due to the characteristics of the disease. However, if a male with a less severe phenotype reproduces, all of his daughters are carriers, and none of his sons will be affected.

Pathophysiology

As in other X-linked diseases, males are affected because they only have one copy of the X chromosome. In Lesch–Nyhan syndrome, the defective gene is that for hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferase (HGPRT), a participant in the 'recycling' of purine nucleotides. Female carriers have a second X chromosome, which contains a "normal" copy of HPRT, preventing the disease from developing, though they may have increased risk of hyperuricemia.

A large number of mutations of HPRT are known. Mutations that only mildly decrease the enzyme's function do not normally cause the severe form of LNS, but do produce a milder form of the disease which still features purine overproduction accompanied by susceptibility to gout and uric acid nephrolithiasis.

Formation of DNA (during cell division) requires nucleotides, molecules that are the building blocks for DNA. The purine bases (adenine and guanine) and pyrimidine bases (thymine and cytosine) are bound to deoxyribose and phosphate and incorporated as necessary. Normally, the nucleotides are synthesized de novo from amino acids and other precursors. A small part, however, is 'recycled' from degraded DNA of broken-down cells. This is termed the "salvage pathway".

HGPRT is the "salvage enzyme" for the purines: it channels hypoxanthine and guanine back into DNA synthesis. Failure of this enzyme has two results:

- Cell breakdown products cannot be reused, and are therefore degraded. This gives rise to increased uric acid, a purine breakdown product.

- The de novo pathway is stimulated due to an excess of PRPP (5-phospho-D-ribosyl-1-pyrophosphate or simply phosphoribosyl-pyrophosphate).

It was previously unclear whether the neurological abnormalities in LNS were due to uric acid neurotoxicity or to a relative shortage in "new" purine nucleotides during essential synthesis steps. Genetic mutations affecting the enzymes of the de novo synthesis pathway may possibly contribute to the disease, although these are rare or unknown. Uric acid has been suggested as a possible cause of neurotoxicity but this is unproven.

Importantly, evidence suggests that one or more lesions in striatal dopaminergic pathways may be central to the neurological deficits, especially the choreoathetoid dyskinesia and self-mutilation. 6-hydroxydopamine toxicity in rodents may be a useful animal model for the syndrome, although this is not proven. However, the link between dopamine and purine synthesis is a nucleotide called guanosine triphosphate or 'GTP'. The first step of dopamine synthesis is GTP cyclohydrolase, and significantly a deficiency of this step produces a syndrome that has a neuropathology similar to LNS. Thus a lack of HGPRT may produce a nucleotide deficiency (specifically: GTP deficiency) disorder, resulting in dopamine deficiency.

Another animal model for LNS has been proposed to arise from oxidative damage, caused by the hyperuricemia accompanying LNS. This is based on the theory that uric acid is a powerful reducing agent and likely an important human antioxidant, in high concentration in blood. Thus, it has been suggested that free radicals, oxidative stress, and reactive oxygen species may play some role in the neuropathology of LNS.

However, some evidence suggests against a role for uric acid in the neuropathology of Lesch–Nyhan syndrome:

- Hyperuricemia associated with classic primary gout, which is caused by low uric acid renal clearance rather than uric acid overproduction, is not associated with neuropathology.

- Hypouricemia occurs in a number of purine disorders, in particular xanthinuria. Despite having complete absence of blood uric acid, xanthinuria patients do not have any neuropathology, nor any other disease states – other than the kidney stones caused by accumulation of insoluble xanthine in lieu of uric acid.

Similarly, uric acid does not penetrate the blood–brain barrier well. However, oxidative stress due to uric acid is now thought to figure in metabolic syndrome, atherosclerosis, and stroke, all syndromes associated with high uric acid levels. Similarly, Superoxide dismutase ( "SOD" ) and SOD-mimetics such as TEMPOL ameliorate the effects of hyperuricemia. Likewise, 6-hydroxydopamine (the putative animal model for Lesch–Nyhan's neuropathy) apparently acts as a neurotoxin by generation of reactive oxygen species. It may be that oxidative stress induced by some other oxypurine such as xanthine causes the disease.

Diagnosis

When an affected individual has fully developed the three clinical elements of uric acid overproduction, neurologic dysfunction, and cognitive and behavioral disturbances, diagnosis of LNS is easily made. Diagnosis is less easy in the early stages, when the three features are not yet obvious. Signs of self-injurious behavior (SIB), results of pedigree analysis and novel molecular biology with genetic testing (called as Diagnostic triad for LNS), often confirms the diagnosis. Suspicion often comes about when the developmental delay of the individual is associated with hyperuricemia. Otherwise, the diagnosis should be alleged when developmental delay is associated with kidney stones (nephrolithiasis) or blood in the urine (hematuria), caused by uric acid stones. For the most part, Lesch–Nyhan syndrome is first suspected when self-inflicted injury behavior develops. However, self-injurious behaviors occur in other conditions, including nonspecific intellectual disability, autism, Rett syndrome, Cornelia de Lange syndrome, Tourette syndrome, familial dysautonomia, choreoacanthocytosis, sensory neuropathy including hereditary sensory neuropathy type 1, and several psychiatric conditions. Of these, only individuals with Lesch–Nyhan syndrome, de Lange syndrome, and familial dysautonomia recurrently display loss of tissue as a consequence. Biting the fingers and lips is a definitive feature of Lesch–Nyhan syndrome; in other syndromes associated with self-injury, the behaviors usually consist of head banging and nonspecific self-mutilation, but not biting of the cheeks, lips and fingers. Lesch–Nyhan syndrome ought to be clearly considered only when self-injurious behavior takes place in conjunction with hyperuricemia and neurological dysfunction.

Diagnostic approach

The urate to creatinine (breakdown product of creatine phosphate in muscle) concentration ratio in urine is elevated. This is a good indicator of acid overproduction. For children under ten years of age with LNS, a urate to creatinine ratio above two is typically found. Twenty-four-hour urate excretion of more than 20 mg/kg is also typical but is not diagnostic. Hyperuricemia (serum uric acid concentration of >8 mg/dL) is often present but not reliable enough for diagnosis. Activity of the HGPRT enzyme in cells from any type of tissue (e.g., blood, cultured fibroblasts, or lymphoblasts) that is less than 1.5% of normal enzyme activity confirms the diagnosis of Lesch–Nyhan syndrome. Molecular genetic studies of the HPRT gene mutations may confirm diagnosis, and are particularly helpful for subsequent 'carrier testing' in at-risk females such as close family relatives on the female side.

Testing

The use of biochemical testing for the detection of carriers is technically demanding and not often used. Biochemical analyses that have been performed on hair bulbs from at risk women have had a small number of both false positive and false negative outcomes. If only a suspected carrier female is available for mutation testing, it may be appropriate to grow her lymphocytes in 6-thioguanine (a purine analogue), which allows only HGPRT-deficient cells to survive. A mutant frequency of 0.5–5.0 × 10 is found in carrier females, while a non-carrier female has a frequency of 1–20 × 10. This frequency is usually diagnostic by itself.

Molecular genetic testing is the most effective method of testing, as HPRT1 is the only gene known to be associated with LNS. Individuals who display the full Lesch–Nyhan phenotype all have mutations in the HPRT1 gene. Sequence analysis of mRNA is available clinically and can be utilized in order to detect HPRT1 mutations in males affected with Lesch–Nyhan syndrome. Techniques such as RT-PCR, multiplex genomic PCR, and sequence analysis (cDNA and genomic DNA), used for the diagnosis of genetic diseases, are performed on a research basis. If RT-PCR tests result in cDNA showing the absence of an entire exon or exons, then multiplex genomic PCR testing is performed. Multiplex genomic PCR testing amplifies the nine exons of the HPRT1 gene as eight PCR products. If the exon in question is deleted, the corresponding band will be missing from the multiplex PCR. However, if the exon is present, the exon is sequenced to identify the mutation, therefore causing exclusion of the exon from cDNA. If no cDNA is created by RT-PCR, then multiplex PCR is performed on the notion that most or all of the gene is obliterated.

Treatment

Treatment for LNS is symptomatic. Gout can be treated with allopurinol to control excessive amounts of uric acid. Kidney stones may be treated with lithotripsy, a technique for breaking up kidney stones using shock waves or laser beams. There is no standard treatment for the neurological symptoms of LNS. Some may be relieved with the drugs carbidopa/levodopa, diazepam, phenobarbital, or haloperidol.

It is essential that the overproduction of uric acid be controlled in order to reduce the risk of nephropathy, nephrolithiasis, and gouty arthritis. The drug allopurinol is utilized to stop the conversion of oxypurines into uric acid, and prevent the development of subsequent arthritic tophi (produced after having chronic gout), kidney stones, and nephropathy, the resulting kidney disease. Allopurinol is taken orally, at a typical dose of 3–20 mg/kg per day. The dose is then adjusted to bring the uric acid level down into the normal range (<3 mg/dL). Most affected individuals can be treated with allopurinol all through life.

No medication is effective in controlling the extrapyramidal motor features of the disease. Spasticity, however, can be reduced by the administration of baclofen or benzodiazepines.

There has previously been no effective method of treatment for the neurobehavioral aspects of the disease. Even children treated from birth with allopurinol develop behavioral and neurologic problems, despite never having had high serum concentrations of uric acid. Self-injurious and other behaviors are best managed by a combination of medical, physical, and behavioral interventions. The self-mutilation is often reduced by using restraints. Sixty percent of individuals have their teeth extracted in order to avoid self-injury, which families have found to be an effective management technique. Because stress increases self-injury, behavioral management through aversive techniques (which would normally reduce self-injury) actually increases self-injury in individuals with LNS. Nearly all affected individuals need restraints to prevent self-injury, and are restrained more than 75% of the time. This is often at their own request, and occasionally involves restraints that would appear to be ineffective, as they do not physically prevent biting. Families report that affected individuals are more at ease when restrained.

The Matheny Medical and Educational Center Matheny | A Non-profit Organization for People with Special Needs in Peapack, NJ, has six Lesch–Nyhan syndrome patients, believed to be the largest concentration of LNS cases in one location, and is recognized as the leading source of information on care issues.

Treatment for LNS patients, according to Gary E. Eddey, MD, medical director, should include: 1) Judicious use of protective devices; 2) Utilization of a behavioral technique commonly referred to as 'selective ignoring' with redirection of activities; and 3) Occasional use of medications.

An article in the August 13, 2007 issue of The New Yorker magazine, written by Richard Preston, discusses "deep-brain stimulation" as a possible treatment. It has been performed on a few patients with Lesch–Nyhan syndrome by Dr. Takaomi Taira in Tokyo and by a group in France led by Dr. Philippe Coubes. Some patients experienced a decrease in spastic self-injurious symptoms. The technique was developed for treating people with Parkinson's disease, according to Preston, over 20 years ago. The treatment involves invasive surgery to place wires that carry a continuous electric current into a specific region of the brain.

An encouraging advance in the treatment of the neurobehavioural aspects of LNS was the publication in the October, 2006 issue of Journal of Inherited Metabolic Disease of an experimental therapy giving oral S-adenosyl-methionine (SAMe). This drug is a nucleotide precursor that provides a readily absorbed purine, which is known to be transported across the blood–brain barrier. Administration of SAMe to adult LNS patients was shown to provide improvement in neurobehavioural and other neurological attributes. The drug is available without prescription and has been widely used for depression, but its use for treating LNS should be undertaken only under strict medical supervision, as side effects are known.

Prognosis

The prognosis for individuals with severe LNS is poor. Death is usually due to kidney failure or complications from hypotonia, in the first or second decade of life. Less severe forms have better prognosis.

History

Michael Lesch was a medical student at Johns Hopkins and William Nyhan, a pediatrician and biochemical geneticist, was his mentor when the two identified LNS and its associated hyperuricemia in two affected brothers, ages 4 and 8. Lesch and Nyhan published their findings in 1964. Within three years, the metabolic cause was identified by J. Edwin Seegmiller and his colleagues at the NIH.

References

- James, William D.; Berger, Timothy G.; et al. (2006). Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: clinical Dermatology. Saunders Elsevier. p. 546. ISBN 978-0-7216-2921-6.

- ^ "Lesch Nyhan Syndrome". Retrieved 24 February 2022.

- ^ Lesch–Nyhan syndrome. Genetics Home Reference. Retrieved on 2007-05-24.

- Ole Daniel Enersen. Lesch-Nyhan syndrome at Who Named It?

- ^ Lesch-Nyhan Syndrome at NINDS

- Hladnik U, Nyhan WL, Bertelli M (September 2008). "Variable expression of HPRT deficiency in 5 members of a family with the same mutation". Arch. Neurol. 65 (9): 1240–3. doi:10.1001/archneur.65.9.1240. PMID 18779430.

- Cakmakli, H. F.; Torres, R. J.; Menendez, A.; Yalcin-Cakmakli, G.; Porter, C. C.; Puig, J. G.; Jinnah, H. A. (2019). "Macrocytic anemia in Lesch-Nyhan disease and its variants". Genetics in Medicine. 21 (2): 353–360. doi:10.1038/s41436-018-0053-1. PMC 6281870. PMID 29875418.

- Cakmakli, H. F.; Torres, R. J.; Menendez, A.; Yalcin-Cakmakli, G.; Porter, C. C.; Puig, J. G.; Jinnah, H. A. (2018). "Macrocytic Anemia in Lesch-Nyhan Disease and its Variants". Genetics in Medicine. 21 (2): 353–360. doi:10.1038/s41436-018-0053-1. PMC 6281870. PMID 29875418.

- Nagao, T.; Hirokawa, M. (2017). "Diagnosis and treatment of macrocytic anemias in adults". Journal of General and Family Medicine. 18 (5): 200–204. doi:10.1002/jgf2.31. PMC 5689413. PMID 29264027.

- "Lesch Nyhan Syndrome". NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders). Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- Nanagiri, Apoorva; Shabbir, Nadeem (2022). "Lesch Nyhan Syndrome". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. PMID 32310539. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- "Delineation of the motor disorder of Lesch–Nyhan disease". academic.oup.com. Brain. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- "SSA - POMS: DI 23022.220 - Lesch-Nyhan Syndrome (LNS) - 08/28/2020". secure.ssa.gov. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- Cauwels RG, Martens LC (2005). "Self-mutilation behaviour in Lesch–Nyhan syndrome". Journal of Oral Pathology and Medicine. 34 (9): 573–5. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0714.2005.00330.x. PMID 16138897.

- ^ Gualtieri, C. Thomas (2002). Brain Injury and Mental Retardation: Psychopharmacology and Neuropsychiatry, p. 257. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 0-7817-3473-8.

- "Attenuated variants of Lesch-Nyhan disease". academic.oup.com. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- Puig; Mateos; Torres; Buño (1998). "Purine metabolism in female heterozygotes for hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferase deficiency". European Journal of Clinical Investigation. 28 (11). Wiley: 950–957. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2362.1998.00392.x. ISSN 0014-2972. PMID 9824441. S2CID 23770074.

- Augoustides-Savvopoulou P, Papachristou F, Fairbanks LD, Dimitrakopoulos K, Marinaki AM, Simmonds HA (2002). "Partial hypoxanthine-Guanine phosphoribosyltransferase deficiency as the unsuspected cause of renal disease spanning three generations: a cautionary tale". Pediatrics. 109 (1): E17. doi:10.1542/peds.109.1.e17. PMID 11773585.

- Lesch–Nyhan syndrome. NCBI Genes and disease. Retrieved on 2007-04-12

- Proctor, P (26 December 1970). "Levodopa Side-effects and the Lesch-Nyhan Syndrome". Lancet. 296 (7687): 1367. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(70)92399-8. PMID 4098945.

- Nyhan WL (2000). "Dopamine function in Lesch–Nyhan disease". Environ. Health Perspect. 108 (Suppl 3): 409–11. doi:10.2307/3454529. JSTOR 3454529. PMC 1637829. PMID 10852837.

- ^ Visser J, Smith D, Moy S, Breese G, Friedmann T, Rothstein J, Jinnah H (2002). "Oxidative stress and dopamine deficiency in a genetic mouse model of Lesch–Nyhan disease". Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 133 (2): 127–39. doi:10.1016/S0165-3806(02)00280-8. PMID 11882343.

- Breese GR, Knapp DJ, Criswell HE, Moy SS, Papadeas ST, Blake BL (2005). "The neonate-6-hydroxydopamine-lesioned rat: a model for clinical neuroscience and neurobiological principles". Brain Res. Brain Res. Rev. 48 (1): 57–73. doi:10.1016/j.brainresrev.2004.08.004. PMID 15708628. S2CID 22599841.

- Deutsch SI; Long KD; Rosse RB; Mastropaolo J; Eller J. (Jan–Feb 2005). "Hypothesized deficiency of guanine-based purines may contribute to abnormalities of neurodevelopment, neuromodulation, and neurotransmission in Lesch–Nyhan syndrome". Clin. Neuropharmacol. 28 (1): 28–37. doi:10.1097/01.wnf.0000152043.36198.25. PMID 15711436. S2CID 36457793.

- Saugstad O, Marklund S (1988). "High activities of erythrocyte glutathione peroxidase in patients with the Lesch–Nyhan syndrome". Acta Med Scand. 224 (3): 281–5. doi:10.1111/j.0954-6820.1988.tb19374.x. PMID 3239456.

- Bavaresco C, Chiarani F, Matté C, Wajner M, Netto C, de Souza Wyse A (2005). "Effect of hypoxanthine on Na+,K+-ATPase activity and some parameters of oxidative stress in rat striatum". Brain Res. 1041 (2): 198–204. doi:10.1016/j.brainres.2005.02.012. PMID 15829228. S2CID 22575382.

- Kudo M; Moteki T; Sasaki T; Konno Y; Ujiie S; Onose A; Mizugaki M; Ishikawa M; Hiratsuka M. (March 2008). "Functional characterization of human xanthine oxidase allelic variants". Pharmacogenet Genomics. 18 (3): 243–51. doi:10.1097/FPC.0b013e3282f55e2e. PMID 18300946. S2CID 8140455.

- Tewari, Nitesh; Mathur, Vijay Prakash; Sardana, Divesh; Bansal, Kalpana (2017). "Lesch-Nyhan syndrome: The saga of metabolic abnormalities and self-injurious behavior". Intractable & Rare Diseases Research. 6 (1): 65–68. doi:10.5582/irdr.2016.01076. ISSN 2186-361X. PMC 5359358. PMID 28357186.

- Tewari N, Mathur VP, Sardana D, Bansal K (February 2017). "Lesch-Nyhan syndrome: The saga of metabolic abnormalities and self-injurious behavior". Intractable Rare Dis Res. 6 (1): 65–68. doi:10.5582/irdr.2016.01076. PMC 5359358. PMID 28357186.

- Preston, Richard (August 2007). "An Error in the Code". The New Yorker. p. 30. Archived from the original on 2012-09-05. Retrieved 2008-09-14.

- Glick N (October 2006). "Dramatic reduction in self-injury in Lesch–Nyhan disease following S-adenosylmethionine administration". J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 29 (5): 687. doi:10.1007/s10545-006-0229-8. PMID 16906475. S2CID 33099025.

- Nyhan WL (1997). "The recognition of Lesch–Nyhan syndrome as an inborn error of purine metabolism" (PDF). J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 20 (2): 171–8. doi:10.1023/A:1005348504512. PMID 9211189. S2CID 37373603.

- Lesch M, Nyhan WL (1964). "A familial disorder of uric acid metabolism and central nervous system function". Am. J. Med. 36 (4): 561–70. doi:10.1016/0002-9343(64)90104-4. PMID 14142409.

- Seegmiller JE, Rosenbloom FM, Kelley WN (1967). "Enzyme defect associated with a sex-linked human neurological disorder and excessive purine synthesis". Science. 155 (770): 1682–4. Bibcode:1967Sci...155.1682S. doi:10.1126/science.155.3770.1682. PMID 6020292. S2CID 45609754.

External links

- Lesch-Nyhan Syndrome at NIH's Office of Rare Diseases

- GeneReview/NIH/UW entry on Lesch–Nyhan syndrome

- National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD)

| Classification | D |

|---|---|

| External resources |

| Inborn error of purine–pyrimidine metabolism | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Purine metabolism |

| ||||||

| Pyrimidine metabolism |

| ||||||

| X-linked disorders | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|