Fictional character

| King Kong | |

|---|---|

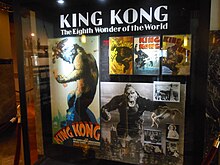

| King Kong character | |

King Kong as featured in promotional material for the original 1933 film King Kong as featured in promotional material for the original 1933 film | |

| First appearance | King Kong (1933) |

| Created by | Merian C. Cooper |

| Portrayed by | Various

|

| Voiced by | Various

|

| Binomial nomenclature |

|

| In-universe information | |

| Aliases | The Eighth Wonder of the World The Beast |

| Species | Giant gorilla-like ape |

| Weapon | Axe (MonsterVerse) |

| Family |

|

| Home |

|

King Kong, also referred to simply as Kong, is a fictional giant monster, or kaiju, resembling a gorilla, who has appeared in various media since 1933. Kong has been dubbed the King of the Beasts, and over time, it would also be bestowed the title of the Eighth Wonder of the World, a widely recognized expression within the franchise. His first appearance was in the novelization of the 1933 film King Kong from RKO Pictures, with the film premiering a little over two months later.

A sequel quickly followed that same year with The Son of Kong, featuring Little Kong, also known as "Kiko". The Japanese film company Toho later produced King Kong vs. Godzilla (1962), featuring a giant Kong battling Toho's Godzilla, and King Kong Escapes (1967), a film loosely based on Rankin/Bass' The King Kong Show (1966–1969). In 1976, Dino De Laurentiis produced a modern remake of the original film directed by John Guillermin. A sequel, King Kong Lives, followed a decade later featuring a Lady Kong. Another remake of the original, set in 1933, was released in 2005 by filmmaker Peter Jackson.

Kong: Skull Island (2017), set in 1973, is part of Warner Bros. Pictures and Legendary Entertainment's Monsterverse, which began with a reboot of Godzilla in 2014. A sequel, Godzilla vs. Kong, once again pitting the characters against one another, was released in 2021. It was followed by the film Godzilla x Kong: The New Empire in 2024, which featured more of Kong's kind.

The character is an international pop culture icon, having inspired a number of sequels, remakes, spin-offs, imitators, parodies, cartoons, books, comics, video games, theme park rides, and a stage play. King Kong has also crossed over into other franchises, such as Planet of the Apes, and encountered characters from other franchises in crossover media, such as the Toho movie monster Godzilla, pulp characters Doc Savage and Tarzan, and the Justice League. His role in the different narratives varies, ranging from an egregious monster to a tragic antihero.

Overview

The King Kong character was conceived and created by American filmmaker Merian C. Cooper. In the original film, the character's name is Kong, a name given to him by the inhabitants of the fictional "Skull Island" in the Indian Ocean, where Kong lives along with other oversized animals, such as plesiosaurs, pterosaurs, and various dinosaurs. An American film crew, led by Carl Denham, captures Kong and takes him to New York City to be exhibited as the "Eighth Wonder of the World".

Kong escapes and climbs the Empire State Building, only to fall from the skyscraper after being attacked by weaponized biplanes. Denham comments, "It wasn't the aeroplanes, it was beauty killed the beast", for he climbs the building in the first place only in an attempt to protect Ann Darrow, an actress originally kidnapped by the natives of the island and offered up to Kong as a sacrifice (in the 1976 remake, her character is named "Dwan").

A pseudo-documentary about Skull Island that appears on the DVD for the 2005 remake (originally seen on the Sci-Fi Channel at the time of its theatrical release) gives Kong's scientific name as Megaprimatus kong ("Megaprimatus", deriving from the prefix "mega-" and the Latin words "primate" and "primatus", means "big primate" or "big supreme being") and states that his species may be related to Gigantopithecus, but that genus of giant ape is more closely related to orangutans than to gorillas.

Conception and creation

Merian C. Cooper became fascinated by gorillas at the age of 6. In 1899, he was given a book from his uncle called Explorations and Adventures in Equatorial Africa. The book, written in 1861, chronicled the adventures of Paul Du Chaillu in Africa and his various encounters with the natives and wildlife there. Cooper became fascinated with the stories involving the gorillas, in particular, Du Chaillu's depiction of a particular gorilla known for its "extraordinary size", that the natives described as "invincible" and the "King of the African Forest". When Du Chaillu and some natives encountered a gorilla later in the book he described it as a "hellish dream creature" that was "half man, half beast".

As an adult, Cooper became involved in the motion picture industry. While filming The Four Feathers in Africa, he came into contact with a family of baboons. This gave him the idea to make a picture about primates. A year later when he got to RKO, Cooper wanted to film a "terror gorilla picture". As the story was being fleshed out, Cooper decided to make his gorilla giant sized. Cooper stated that the idea of Kong fighting warplanes on top of a building came from him seeing a plane flying over the New York Insurance Building, then the tallest building in the world. He came up with the ending before the rest of the story as he stated: "Without any conscious effort of thought I immediately saw in my mind's eye a giant gorilla on top of the building". Cooper also was influenced by Douglas Burden's accounts of the Komodo dragon, and wanted to pit his terror gorilla against dinosaur-sized versions of these reptiles, stating to Burden: "I also had firmly in mind to giantize both the gorilla and your dragons to make them really huge. However I always believed in personalizing and focusing attention on one main character and from the very beginning I intended to make it the gigantic gorilla, no matter what else I surrounded him with". Around this time, Cooper began to refer to his project as a "giant terror gorilla picture" featuring "a gigantic semi-humanoid gorilla pitted against modern civilization".

When designing King Kong, Cooper wanted him to be a nightmarish gorilla monster. As he described Kong in a 1930 memo: "His hands and feet have the size and strength of steam shovels; his girth is that of a steam boiler. This is a monster with the strength of a hundred men. But more terrifying is the head—a nightmare head with bloodshot eyes and jagged teeth set under a thick mat of hair, a face half-beast half-human". Willis O'Brien created an oil painting depicting the giant gorilla menacing a jungle heroine and hunter for Cooper, but when it came time for O'Brien and Marcel Delgado to sculpt the animation model, Cooper decided to backpedal on the half-human look for the creature and became adamant that Kong be a gorilla. O'Brien on the other hand, wanted him to be almost human-like to gain audience empathy, and told Delgado to "make that ape almost human". Cooper laughed at the end result, saying that it looked like a cross between a monkey and a man with very long hair. For the second model, O'Brien again asked Delgado to add human features but to tone it down somewhat. The end result (which was rejected) was described as looking like a missing link. Disappointed, Cooper stated, "I want Kong to be the fiercest, most brutal, monstrous damned thing that has ever been seen!" On December 22, 1931, Cooper got the dimensions of a bull gorilla from the American Museum of Natural History telling O'Brien, "Now that's what I want!" When the final model was created, it had the basic look of a gorilla but managed to retain some human-like qualities. For example, Delgado streamlined the body by removing the distinctive paunch and rump of a gorilla. O'Brien would incorporate some characteristics and nuances of an earlier creature he had created in 1915 for the silent short The Dinosaur and the Missing Link into the general look and personality of Kong, even going as far as to refer to the creature as "Kong's ancestor". When it came time to film, Cooper agreed that Kong should walk upright at times (mostly in the New York sequences) in order to appear more intimidating.

Etymology

Merian C. Cooper said he was very fond of strong, hard-sounding words that started with the letter "K". Some of his favorite words were "Komodo", "Kodiak" and "Kodak". When Cooper was envisioning his giant terror gorilla idea, he wanted to capture a real gorilla from the Congo and have it fight a real Komodo dragon on Komodo Island (this scenario would eventually evolve into Kong's battle with the tyrannosaur on Skull Island when the film was produced a few years later at RKO). Cooper's friend Douglas Burden's trip to the island of Komodo and his encounter with the Komodo dragons was a big influence on the Kong story. Cooper was fascinated by Burden's adventures as chronicled in his book Dragon Lizards of Komodo where he referred to the animal as the "King of Komodo". It was this phrase along with "Komodo" and "Kongo" [sic] (and his overall love for hard sounding "K"-words) that gave him the idea to name the giant ape "Kong". He loved the name, as it had a "mystery sound" to it.

After Cooper got to RKO, British mystery writer Edgar Wallace was contracted to write the first draft of the screen story. It was simply referred to as "The Beast". RKO executives were unimpressed with the bland title. David O. Selznick suggested Jungle Beast as the film's new title, but Cooper was unimpressed and wanted to name the film after the main character. He stated he liked the "mystery word" aspect of Kong's name and that the film should carry "the name of the leading mysterious, romantic, savage creature of the story" such as with Dracula and Frankenstein. RKO sent a memo to Cooper suggesting the titles Kong: King of Beasts, Kong: The Jungle King, and Kong: The Jungle Beast, which combined his and Selznick's proposed titles. As time went on, Cooper would eventually name the story simply Kong while Ruth Rose was writing the final version of the screenplay. Because David O. Selznick thought that audiences would think that the film, with the one word title of Kong, would be mistaken as a docudrama like Grass and Chang, which were one-word titled films that Cooper had earlier produced, he added the "King" to Kong's name in order to differentiate it.

Appearances and abilities

In his first appearance in King Kong (1933), Kong was a gigantic prehistoric ape. While gorilla-like in appearance, he had a vaguely humanoid look and at times walked upright in an anthropomorphic manner.

Like most simians, Kong possesses semi-human intelligence and great physical strength. Kong's size changes drastically throughout the course of the film. While creator Merian C. Cooper envisioned Kong as being "40 to 50 feet tall", animator Willis O'Brien and his crew built the models and sets scaling Kong to be only 18 feet (5.5 m) tall on Skull Island, and rescaled to be 24 feet (7.3 m) tall in New York.

This did not stop Cooper from playing around with Kong's size as he directed the special effect sequences; by manipulating the sizes of the miniatures and the camera angles, he made Kong appear a lot larger than O'Brien wanted, even as large as 60 feet (18.3 m) in some scenes.

As Cooper said in an interview:

I was a great believer in constantly changing Kong's height to fit the settings and the illusions. He's different in almost every shot; sometimes he's only 18 feet tall and sometimes 60 feet or larger. This broke every rule that O'Bie and his animators had ever worked with, but I felt confident that if the scenes moved with excitement and beauty, the audience would accept any height that fitted into the scene. For example, if Kong had only been 18 feet high on the top of the Empire State Building, he would have been lost, like a little bug; I constantly juggled the heights of trees and dozens of other things. The one essential thing was to make the audience enthralled with the character of Kong so that they wouldn't notice or care that he was 18 feet high or 40 feet, just as long as he fitted the mystery and excitement of the scenes and action.

Concurrently, the Kong bust made for the film was built in scale with a 40-foot (12.2 m) ape, while the full sized hand of Kong was built in scale with a 70-foot (21.3 m) ape. Meanwhile, RKO's promotional materials listed Kong's official height as 50 feet (15.2 m).

In the 1960s, Toho Studios from Japan licensed the character for the films King Kong vs. Godzilla and King Kong Escapes. (See below)

In 1975, Italian producer Dino De Laurentiis paid RKO for the remake rights to King Kong. This resulted in King Kong (1976). This Kong was an upright walking anthropomorphic ape, appearing even more human-like than the original. Also like the original, this Kong had semi-human intelligence and vast strength. In the 1976 film, Kong was scaled to be 42 feet (12.8 m) tall on Skull island and rescaled to be 55 feet (16.8 m) tall in New York. Ten years later, Dino De Laurentiis got the approval from Universal to do a sequel called King Kong Lives. This Kong had more or less the same appearance and abilities, but tended to walk on his knuckles more often and was enlarged, scaled to 60 feet (18.3 m).

Universal Studios had planned to do a King Kong remake as far back as 1976. They finally followed through almost 30 years later, with a three-hour film directed by Peter Jackson. Jackson opted to make Kong a gigantic silverback gorilla without any anthropomorphic features. This Kong looked and behaved more like a real gorilla: he had a large herbivore's belly, walked on his knuckles without any upright posture, and even beat his chest with his palms as opposed to clenched fists. In order to ground his Kong in realism, Jackson and the Weta Digital crew gave a name to his fictitious species Megaprimatus Kong and suggested it to have evolved from the Gigantopithecus. Kong was the last of his kind. He was portrayed in the film as being quite old, with graying fur and battle-worn with scars, wounds, and a crooked jaw from his many fights against rival creatures. He is the dominant being on the island, the king of his world. Like his film predecessors, he possesses considerable intelligence and great physical strength and also appears far more nimble and agile. This Kong was scaled to a consistent height of 25 feet (7.6 m) tall on both Skull Island and in New York. Jackson describes his central character:

We assumed that Kong is the last surviving member of his species. He had a mother and a father and maybe brothers and sisters, but they're dead. He's the last of the huge gorillas that live on Skull Island ... when he goes ... there will be no more. He's a very lonely creature, absolutely solitary. It must be one of the loneliest existences you could ever possibly imagine. Every day, he has to battle for his survival against very formidable dinosaurs on the island, and it's not easy for him. He's carrying the scars of many former encounters with dinosaurs. I'm imagining he's probably 100 to 120 years old by the time our story begins. And he has never felt a single bit of empathy for another living creature in his long life; it has been a brutal life that he's lived.

In the 2017 film Kong: Skull Island, Kong is scaled to be 104 feet (31.7 m) tall, making it the second largest and largest American incarnation in the series until the 2021 film Godzilla vs. Kong, in which he became the largest incarnation in the series, standing at 337 feet (102.7 m). Director Jordan Vogt-Roberts stated in regard to Kong's immense stature:

The thing that most interested me was, how big do you need to make , so that when someone lands on this island and doesn't believe in the idea of myth, the idea of wonder – when we live in a world of social and civil unrest, and everything is crumbling around us, and technology and facts are taking over – how big does this creature need to be, so that when you stand on the ground and you look up at it, the only thing that can go through your mind is: "That's a god!"

He also stated that the original 1933 look was the inspiration for the design:

We sort of went back to the 1933 version in the sense that he's a bipedal creature that walks in an upright position, as opposed to the anthropomorphic, anatomically correct silverback gorilla that walks on all fours. Our Kong was intended to say, like, this isn't just a big gorilla or a big monkey. This is something that is its own species. It has its own set of rules, so we can do what we want and we really wanted to pay homage to what came before ... and yet do something completely different, and if anything, our Kong is meant to be a throwback to the '33 version. I don't think there's much similarity at all between our version and Peter 's Kong. That version is very much a scaled-up silverback gorilla, and ours is something that is slightly more exaggerated. A big mandate for us was, "How do we make this feel like a classic movie monster"?

Co-producer Mary Parent also stated that Kong is still young and not fully grown as she explains that "Kong is an adolescent when we meet him in the film; he's still growing into his role as alpha".

Ownership rights

While one of the most famous movie icons in history, King Kong's intellectual property status has been questioned since his creation, featuring in numerous allegations and court battles. The rights to the character have always been split up with no single exclusive rights holder. Different parties have also contested that various aspects are public domain material and therefore ineligible for copyright status.

When Merian C. Cooper created King Kong, he assumed that he owned the character, which he had conceived in 1929, outright. Cooper maintained that he had only licensed the character to RKO for the initial film and sequel, but had otherwise owned his own creation. In 1935, Cooper began to feel something was amiss when he was trying to get a Tarzan vs. King Kong project off the ground for Pioneer Pictures (where he had assumed management of the company). After David O. Selznick suggested the project to Cooper, the flurry of legal activity over using the Kong character that followed—Pioneer had become a completely independent company by this time and access to properties that RKO felt were theirs was no longer automatic—gave Cooper pause as he came to realize that he might not have full control over this product of his own imagination after all.

Years later in 1962, Cooper found out that RKO was licensing the character through John Beck to Toho studios in Japan for a film project called King Kong vs. Godzilla. Cooper had assumed his rights were unassailable and was bitterly opposed to the project. In 1963 he filed a lawsuit to enjoin distribution of the movie against John Beck, as well as Toho and Universal (the film's U.S. copyright holder). Cooper discovered that RKO had also profited from licensed products featuring the King Kong character such as model kits produced by Aurora Plastics Corporation. Cooper's executive assistant, Charles B. FitzSimons, said that these companies should be negotiating through him and Cooper for such licensed products and not RKO. In a letter to Robert Bendick, Cooper stated:

My hassle is about King Kong. I created the character long before I came to RKO and have always believed I retained subsequent picture rights and other rights. I sold to RKO the right to make the one original picture King Kong and also, later, Son of Kong, but that was all.

Cooper and his legal team offered up various documents to bolster the case that Cooper owned King Kong and had only licensed the character to RKO for two films, rather than selling him outright. Many people vouched for Cooper's claims, including David O. Selznick, who had written a letter to Mr. A. Loewenthal of the Famous Artists Syndicate in Chicago in 1932 stating (in regard to Kong), "The rights of this are owned by Mr. Merian C. Cooper". Cooper however lost key documents through the years (he discovered these papers were missing after he returned from his World War II military service) such as a key informal yet binding letter from Mr. Ayelsworth (the then-president of the RKO Studio Corp.) and a formal binding letter from Mr. B. B. Kahane (also a former president of RKO Studio Corp.) confirming that Cooper had only licensed the rights to the character for the two RKO pictures and nothing more.

Without these letters, it seemed Cooper's rights were relegated to the Lovelace novelization that he had copyrighted (he was able to make a deal for a Bantam Books paperback reprint and a Gold Key comic adaptation of the novel, but that was all that he could do). Cooper's lawyer had received a letter from John Beck's lawyer, Gordon E. Youngman, that stated:

For the sake of the record, I wish to state that I am not in negotiation with you or Mr. Cooper or anyone else to define Mr. Cooper's rights in respect of King Kong. His rights are well defined, and they are non-existent, except for certain limited publication rights.

In a letter addressed to Douglas Burden, Cooper lamented:

It seems my hassle over King Kong is destined to be a protracted one. They'd make me sorry I ever invented the beast, if I weren't so fond of him! Makes me feel like Macbeth: "Bloody instructions which being taught return to plague the inventor".

The rights over the character did not flare up again until 1975, when Universal Studios and Dino De Laurentiis were fighting over who would be able to do a King Kong remake for release the following year. De Laurentiis came up with $200,000 to buy the remake rights from RKO. When Universal got wind of this, they filed a lawsuit against RKO, claiming that they had a verbal agreement from them regarding the remake. During the legal battles that followed, which eventually included RKO countersuing Universal, as well as De Laurentiis filing a lawsuit claiming interference, Colonel Richard Cooper (Merian's son and now head of the Cooper estate) jumped into the fray.

During the battles, Universal discovered that the copyright of the Lovelace novelization had expired without renewal, thus making the King Kong story a public domain one. Universal argued that they should be able to make a movie based on the novel without infringing on anyone's copyright because the characters in the story were in the public domain within the context of the public domain story. Richard Cooper then filed a cross-claim against RKO claiming that, while the publishing rights to the novel had not been renewed, his estate still had control over the plot/story of King Kong.

In a four-day bench trial in Los Angeles, Judge Manuel Real made the final decision and gave his verdict on November 24, 1976, affirming that the King Kong novelization and serialization were indeed in the public domain, and Universal could make its movie as long as it did not infringe on original elements in the 1933 RKO film, which had not passed into the public domain. Universal postponed their plans to film a King Kong movie, called The Legend of King Kong, for at least 18 months, after cutting a deal with Dino De Laurentiis that included a percentage of box office profits from his remake.

However, on December 6, 1976, Judge Real made a subsequent ruling, which held that all the rights in the name, character, and story of King Kong (outside of the original film and its sequel) belonged to Merian C. Cooper's estate. This ruling, which became known as the "Cooper judgment", expressly stated that it would not change the previous ruling that publishing rights of the novel and serialization were in the public domain. It was a huge victory that affirmed the position Merian C. Cooper had maintained for years. Shortly thereafter, Richard Cooper sold all his rights (excluding worldwide book and periodical publishing rights) to Universal in December 1976. In 1980 Judge Real dismissed the claims that were brought forth by RKO and Universal four years earlier and reinstated the Cooper judgement.

In 1982 Universal filed a lawsuit against Nintendo, which had created an impish ape character called Donkey Kong in 1981 and was reaping huge profits over the video game machines. Universal claimed that Nintendo was infringing on its copyright because Donkey Kong was a blatant rip-off of King Kong. During the court battle and subsequent appeal, the courts ruled that Universal did not have exclusive trademark rights to the King Kong character. The courts ruled that trademark was not among the rights Cooper had sold to Universal, indicating that "Cooper plainly did not obtain any trademark rights in his judgment against RKO, since the California district court specifically found that King Kong had no secondary meaning". While they had a majority of the rights, they did not outright own the King Kong name and character. The courts ruling noted that the name, title, and character of Kong no longer signified a single source of origin so exclusive trademark rights were impossible. The courts also pointed out that the Kong rights were held by three parties:

- RKO owned the rights to the original film and its sequel.

- The Dino De Laurentiis company (DDL) owned the rights to the 1976 remake.

- Richard Cooper owned worldwide book and periodical publishing rights.

The judge then ruled that "Universal thus owns only those rights in the King Kong name and character that RKO, Cooper, or DDL do not own".

The court of appeals would also note:

First, Universal knew that it did not have trademark rights to King Kong, yet it proceeded to broadly assert such rights anyway. This amounted to a wanton and reckless disregard of Nintendo's rights.

Second, Universal did not stop after it asserted its rights to Nintendo. It embarked on a deliberate, systematic campaign to coerce all of Nintendo's third party licensees to either stop marketing Donkey Kong products or pay Universal royalties.

Finally, Universal's conduct amounted to an abuse of judicial process, and in that sense caused a longer harm to the public as a whole. Depending on the commercial results, Universal alternatively argued to the courts, first, that King Kong was a part of the public domain, and then second, that King Kong was not part of the public domain, and that Universal possessed exclusive trademark rights in it. Universal's assertions in court were based not on any good faith belief in their truth, but on the mistaken belief that it could use the courts to turn a profit.

Because Universal misrepresented their degree of ownership of King Kong (claiming they had exclusive trademark rights when they knew that they did not) and tried to have it both ways in court regarding the "public domain" claims, the courts ruled that Universal acted in bad faith (see Universal City Studios, Inc. v. Nintendo Co., Ltd.). They were ordered to pay fines and all of Nintendo's legal costs from the lawsuit. That, along with the fact that the courts ruled that there was simply no likelihood of people confusing Donkey Kong with King Kong, caused Universal to lose the case and the subsequent appeal.

Since the court case, Universal still retains the majority of the character rights. In 1986 they opened a King Kong ride called King Kong Encounter at their Universal Studios Tour theme park in Hollywood (which was destroyed in 2008 by a backlot fire), and followed it up with the Kongfrontation ride at their Orlando park in 1990 (which was closed down in 2002 due to maintenance issues). They also finally made a King Kong film of their own, King Kong (2005). In the summer of 2010, Universal opened a new 3D King Kong ride called King Kong: 360 3-D at their Hollywood park, replacing the destroyed King Kong Encounter. In July 2016, Universal opened a new King Kong attraction called Skull Island: Reign of Kong at Islands of Adventure in Orlando. In July 2013, Legendary Pictures made an agreement with Universal to market, co-finance, and distribute Legendary's films for five years starting in 2014 and ending in 2019, the year that Legendary's similar agreement with Warner Bros. Pictures was set to expire. One year later, at San Diego Comic-Con, Legendary announced (as a product of its partnership with Universal), a King Kong origin story, initially titled Skull Island, with Universal distributing. After the film was retitled Kong: Skull Island, Universal allowed Legendary to move to Warner Bros., so they could do a King Kong and Godzilla crossover film (in the continuity of the 2014 Godzilla movie), since Legendary still had the rights to make more Godzilla movies with Warner Bros. before their contract with Toho expired in 2020.

Richard Cooper, through the Merian C. Cooper Estate, retained publishing rights for the content that Judge Real had ruled on December 6, 1976. In 1990, they licensed a six-issue comic book adaptation of the novelization of the 1933 film to Monster Comics, and commissioned an illustrated novel in 1994 called Anthony Browne's King Kong. In 2013, they became involved with a musical stage play based on the story, called King Kong: The Eighth Wonder of the World which premiered that June in Australia and then on Broadway in November 2018. The production is involved with Global Creatures, the company behind the Walking with Dinosaurs arena show. In 1996, artist/writer Joe DeVito partnered with the Merian C. Cooper estate to write and/or illustrate various publications based on Merian C. Cooper's King Kong property through his company, DeVito ArtWorks, LLC. Through this partnership, DeVito created the prequel/sequel story Skull Island on which DeVito based a pair of original novels relating the origin of King Kong: Kong: King of Skull Island and King Kong of Skull Island. In addition, the Cooper/DeVito collaboration resulted in an origin-themed comic book miniseries with Boom! Studios, an expanded rewrite of the original Lovelace novelization, Merian C. Cooper's King Kong (the original novelization's publishing rights are still in the public domain), and various crossovers with other franchises such as Doc Savage, Tarzan and Planet of the Apes. In 2016, DeVito ArtWorks, through its licensing program, licensed its King Kong property to RocketFizz for use in the marketing of a soft drink called King Kong Cola, and had plans for a live action TV show co-produced between MarVista Entertainment and IM Global. Other products that have been produced through this licensing program include Digital Trading Cards, Board Games, a Virtual Reality Arcade Game, a remake of the original King Kong Glow-In-The-Dark Model Kit, and a video game developed by IguanaBee called Skull Island: Rise of Kong. In April 2016, Joe DeVito sued Legendary Pictures and Warner Bros., producers of the film Kong: Skull Island, for using elements of his Skull Island universe, which he claimed that he created and that the producers had used without his permission. Devito partnered with Dynamite Entertainment to produce comic books and board games based on the property, resulting in the comic book series called King Kong: The Great War published in May 2023. In 2022, DeVito had partnered with Disney to produce a live-action series tentatively called King Kong that explores the origin story of Kong. The series is slated to stream on Disney+. Stephany Folsom is attached to write the series and to be executive produced by James Wan via his production company Atomic Monster.

RKO (whose rights consisted of only the original film and its sequel) signed over the North American, Latin American and Australian distribution rights to its film library to Ted Turner's Turner Entertainment in a period spanning 1986 to 1989. Following a series of mergers and acquisitions, Warner Bros. owns those distribution rights today, with the copyright over the films (including King Kong and The Son of Kong) remaining with RKO Pictures, LLC (various companies distribute the RKO library in other territories). In 1998, Warner Bros. Family Entertainment released the direct-to-video animated musical film The Mighty Kong, which re-tells the plot of the original 1933 film. Nineteen years later, Warners co-produced the film Kong: Skull Island and in 2021 co-produced the film Godzilla vs. Kong, after Legendary Pictures brought the projects over from Universal to build up the MonsterVerse. According to Godzilla Vs. Kong director Adam Wingard, the rights to the character may have also been transferred to Warner Bros.

DDL (whose rights were limited to only their 1976 remake) did a sequel in 1986 called King Kong Lives (but they still needed Universal's permission to do so). Today most of DDL's film library is owned by StudioCanal, which includes the rights to these two films. The domestic (North American) rights to the 1976 King Kong film still remain with the film's original distributor Paramount Pictures, with Trifecta Entertainment & Media handling television rights to the film via their license with Paramount.

Toho incarnations

In the 1960s, Japanese studio Toho licensed the character from RKO and produced two films that featured the character, King Kong vs. Godzilla (1962) and King Kong Escapes (1967). Toho's interpretation differed greatly from the original in size and abilities. Among kaiju, King Kong was suggested to be among the most powerful in terms of raw physical force, possessing strength and durability that rivaled that of Godzilla. As one of the few mammal-based kaiju, Kong's most distinctive feature was his intelligence. He demonstrated the ability to learn and adapt to an opponent's fighting style, identify and exploit weaknesses in an enemy, and utilize his environment to stage ambushes and traps.

In King Kong vs. Godzilla, Kong was scaled to be 45 m (148 ft) tall. This version of Kong was given the ability to harvest electricity as a weapon and draw strength from electrical voltage. In King Kong Escapes, Kong was scaled to be 20 m (66 ft) tall. This version was more similar to the original, where he relied on strength and intelligence to fight and survive. Rather than residing on Skull Island, Toho's version of Kong resided on Faro Island in King Kong vs. Godzilla and on Mondo Island in King Kong Escapes.

In 1966, Toho planned to produce Operation Robinson Crusoe: King Kong vs. Ebirah as a co-production with Rankin/Bass Productions, but Ishirō Honda was unavailable at the time to direct the film and, as a result, Rankin/Bass backed out of the project, along with the King Kong license. Toho still proceeded with the production, replacing King Kong with Godzilla at the last minute and shot the film as Ebirah, Horror of the Deep. Elements of King Kong's character remained in the film, reflected in Godzilla's uncharacteristic behavior and attraction to the female character Daiyo. Toho and Rankin/Bass later negotiated their differences and co-produced King Kong Escapes in 1967, loosely based on Rankin/Bass' animated show.

Toho Studios wanted to remake King Kong vs. Godzilla, which was the most successful of the entire Godzilla series of films, in 1991 to celebrate the 30th anniversary of the film, as well as to celebrate Godzilla's upcoming 40th anniversary, but they were unable to obtain the rights to use Kong, and initially intended to use Mechani-Kong as Godzilla's next adversary. It was soon learned that even using a mechanical creature who resembled Kong would be just as problematic legally and financially for them. As a result, the film became Godzilla vs. King Ghidorah, with one last failed attempt made to use Kong in 2004's Godzilla: Final Wars.

Appearances

Main article: King Kong (franchise)Film

| Film | Release date | Director(s) | Story by | Screenwriter(s) | Producer(s) | Distributor(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| King Kong | March 2, 1933 (1933-03-02) | Merian C. Cooper and Ernest B. Schoedsack | Edgar Wallace and Merian C. Cooper | James Creelman and Ruth Rose | Merian C. Cooper and Ernest B. Schoedsack | RKO Pictures |

| Son of Kong | December 22, 1933 (1933-12-22) | Ernest B. Schoedsack | Ruth Rose | Ernest B. Schoedsack | ||

| King Kong vs. Godzilla | August 11, 1962 (1962-08-11) | Ishirō Honda (Japan) Thomas Montgomery (U.S.) |

Shinichi Sekizawa (Japan) Paul Mason and Bruce Howard (U.S.) |

Tomoyuki Tanaka (Japan) John Beck (U.S.) |

Toho Co., Ltd. (Japan) Universal International (U.S.) | |

| King Kong Escapes | July 22, 1967 (1967-07-22) | Ishirō Honda | Arthur Rankin Jr. | Takeshi Kimura | Tomoyuki Tanaka and Arthur Rankin Jr. | |

| King Kong | December 17, 1976 (1976-12-17) | John Guillermin | Lorenzo Semple Jr. | Dino De Laurentiis | Paramount Pictures | |

| King Kong Lives | December 19, 1986 (1986-12-19) | Ronald Shusett and Steven Pressfield | Martha Schumacher | De Laurentiis Entertainment Group | ||

| King Kong | December 14, 2005 (2005-12-14) | Peter Jackson | Fran Walsh, Philippa Boyens and Peter Jackson | Jan Blenkin, Carolynne Cunningham, Fran Walsh and Peter Jackson | Universal Pictures | |

| Kong: Skull Island | March 10, 2017 (2017-03-10) | Jordan Vogt-Roberts | John Gatins | Dan Gilroy, Max Borenstein, and Derek Connolly | Thomas Tull, Jon Jashni, Alex Garcia and Mary Parent | Warner Bros. |

| Godzilla vs. Kong | March 24, 2021 (2021-03-24) | Adam Wingard | Terry Rossio, Michael Dougherty, and Zach Shields | Eric Pearson and Max Borenstein | Thomas Tull, Jon Jashni, Brian Rogers, Mary Parent, Alex Garcia, and Eric McLeod | |

| Godzilla x Kong: The New Empire | March 29, 2024 (2024-03-29) | Terry Rossio, Adam Wingard, and Simon Barrett | Terry Rossio, Simon Barrett, and Jeremy Slater | |||

Television

Four television shows have been based on King Kong: The King Kong Show (1966), Kong: The Animated Series (2000), Kong: King of the Apes (2016), and Skull Island (2023).

A live-action series exploring the origin story of Kong is in development for Disney+, written by Stephany Folsom and executive produced by James Wan via Atomic Monster.

King Kong appeared in episode 27 of the anime show The New Adventures of Gigantor titled King Kong vs Tetsujin (キングコング対鉄人). This episode aired April 10 1981, and featured King Kong battling the giant robot hero Gigantor. In the story it turns out it was just a robot disguised as King Kong. To avoid any copyright issue the episode was renamed The Great Garkonga when it was dubbed into English.

The character appears in the final episode of season one of the television series Monarch: Legacy of Monsters.

Cultural impact

Main article: King Kong in popular culture| This section may contain irrelevant references to popular culture. Please help Misplaced Pages to improve this section by removing the content or adding citations to reliable and independent sources. (October 2018) |

King Kong, as well as the series of films featuring him, have been featured many times in popular culture outside of the films themselves, in forms ranging from straight copies to parodies and joke references, and in media from comic books to video games.

The Beatles' 1968 animated film Yellow Submarine includes a scene of the characters opening a door to reveal King Kong abducting a woman from her bed.

The Simpsons episode "Treehouse of Horror III" features a segment called "King Homer" which parodies the plot of the original film, with Homer as Kong and Marge in the Ann Darrow role. It ends with King Homer marrying Marge and eating her father.

The 2005 animated film Chicken Little features a scene parodying King Kong, as Fish out of Water starts stacking magazines thrown in a pile, eventually becoming a model of the Empire State Building and some plane models, as he imitates King Kong in the iconic scene from the original film.

The British comedy TV series The Goodies made an episode called "Kitten Kong", in which a giant cat called Twinkle roams the streets of London, knocking over the British Telecom Tower.

The controversial World War II Dutch resistance fighter Christiaan Lindemans—eventually arrested on suspicion of having betrayed secrets to the Nazis—was nicknamed "King Kong" due to his being exceptionally tall.

Frank Zappa and The Mothers of Invention recorded an instrumental about "King Kong" in 1967 and featured it on the album Uncle Meat. Zappa went on to make many other versions of the song on albums such as Make a Jazz Noise Here, You Can't Do That on Stage Anymore, Vol. 3, Ahead of Their Time, and Beat the Boots.

The Kinks recorded a song called "King Kong" as the B-side to their 1969 "Plastic Man" single.

In 1972, a 550 cm (18 ft) fiberglass statue of King Kong was erected in Birmingham, England.

The second track of The Jimmy Castor Bunch album Supersound from 1975 is titled "King Kong".

Filk Music artists Ookla the Mok's "Song of Kong", which explores the reasons why King Kong and Godzilla should not be roommates, appears on their 2001 album Smell No Evil.

Daniel Johnston wrote and recorded a song called "King Kong" on his fifth self-released music cassette, Yip/Jump Music in 1983, rereleased on CD and double LP by Homestead Records in 1988. The song is an a cappella narrative of the original movie's story line. Tom Waits recorded a cover version of the song with various sound effects on the 2004 release, The Late Great Daniel Johnston: Discovered Covered.

ABBA recorded "King Kong Song" for their 1974 album Waterloo. Although later singled out by ABBA songwriters Benny Andersson and Björn Ulvaeus as one of their weakest tracks, it was released as a single in 1977 to coincide with the 1976 film playing in theaters.

Tenacious D wrote "Kong" to be released as a bonus track for the Japanese version of The Pick of Destiny to accompany the film.

The 1994 Nintendo Game Boy title Donkey Kong features the eponymous character grow to a gargantuan size as the game's final boss.

See also

References

Citations

- ^ Ryfle 1998, p. 353.

- Ryfle 1998, p. 178.

- Lambie, Ryan (March 10, 2017). "The Struggles of King Kong '76". Den of Geek. Archived from the original on April 3, 2018. Retrieved March 28, 2018.

- Sullivan, Kevin (May 11, 2016). "Toby Kebbell clears up Kong: Skull Island rumors". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on May 20, 2016. Retrieved May 11, 2016.

- "Kong: Skull Island (2017) End Credits". Legendary Pictures. Archived from the original on June 13, 2017. Retrieved April 9, 2017.

- Failes, Ian (April 15, 2021). "How Kong's ocean showdown with Godzilla was made". befores & afters. Archived from the original on April 15, 2021. Retrieved April 15, 2021.

- "Extract: "Animating Kong" — Godzilla vs Kong visual effects by Weta Digital". The Illusion Almanac. May 28, 2021. Archived from the original on March 29, 2024. Retrieved March 29, 2024.

- Coley, Samantha (May 5, 2024). "The Best Fight Sequence in 'Godzilla x Kong: The New Empire' Almost Didn't Make the Cut". Collider. Archived from the original on June 8, 2024. Retrieved June 7, 2024.

- "Murray Spivack is the voice of King Kong in King Kong (1933)". BehindTheVoiceActors. Archived from the original on March 7, 2022. Retrieved April 9, 2021.

- Trumbore, Dave (September 19, 2017). "'Transformers': Peter Cullen and Frank Welker on the Evolution of Optimus Prime and Megatron". Collider. Archived from the original on January 31, 2019. Retrieved January 30, 2019.

- "Peter Elliott is the voice of King Kong in King Kong Lives". BehindTheVoiceActors. Archived from the original on March 7, 2022. Retrieved April 9, 2021.

- ^ "Voices of King Kong". BehindTheVoiceActors. Archived from the original on May 10, 2021. Retrieved April 9, 2021.

- "Bringing Kong to Life Part 1 - Motion Capture". King Kong DVD Extras. April 29, 2010. Archived from the original on May 12, 2021. Retrieved April 12, 2021.

- "Seth Green is the voice of King Kong in The LEGO Batman Movie". BehindTheVoiceActors. Archived from the original on April 29, 2021. Retrieved April 9, 2021.

- "Dave Fennoy is the voice of King Kong in Skull Island: Rise of Kong". BehindTheVoiceActors. Retrieved July 25, 2024.

- "Misty Lee is the voice of Baby King Kong in Skull Island: Rise of Kong". BehindTheVoiceActors. Retrieved July 25, 2024.

- The following sources have described King Kong as a kaiju:

- Ambrose, Kristy (January 4, 2021). "Godzilla: 10 things you never knew about the kaiju he fought". Screen Rant. Retrieved January 4, 2021.

- Robertson, Josh. "The 15 most badass kaiju monsters of all time". Complex Networks. Retrieved May 18, 2014.

- King of the Beasts:

- Vaz 2005, p. 220

- Anderson, Brian (February 16, 2024). "The Top 10 Godzilla Movies, Ranked". Comic Book Resources.

- Minazzo, William (March 6, 2024). "The Evolution Of Kong: King Of The Beasts!". Supanova Expo.

- @Cineverse_ent (March 2, 2024). "The King of the Beasts turns 91 years old today!" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- Espinoza, Alexa (November 12, 2016). "New trailer for 'Kong: Skull Island' announced".

- Sell, Paul (August 17, 2016). "The history of King Kong: A prelude to Skull Island".

- "King Kong: 80th anniversary". March 15, 2013. Retrieved December 11, 2023.

- Spray, Aaron (December 7, 2022). "From King Kong To The Crazy Horse Memorial: What Is The Eighth Wonder Of The World?". Retrieved April 20, 2023.

- Erb, Cynthia, 1998, Tracking King Kong: A Hollywood Icon in World Culture, Wayne State University Press, ISBN 0-8143-2686-2.

- Boland, Michaela (February 9, 2009). "Global Creatures takes on 'Kong'". Variety. Retrieved March 4, 2010.

- Gross, Ed (August 9, 2017). "Kong on the Planet of the Apes: Exclusive First Look at the Comic Mini-Series". Empire. Archived from the original on August 9, 2017. Retrieved May 13, 2022.

- Morrison, Matt (July 20, 2023). "Justice League to Fight Godzilla and King Kong in Upcoming Crossover". Superherohype. Retrieved October 20, 2023.

- The World of Kong: A Natural History of Skull Island, p. 210 Archived August 4, 2020, at the Wayback Machine

- Vaz 2005, pp. 14–15.

- "Getting That Monkey Off His Creator's Back". The New York Times. August 13, 2005. Archived from the original on October 18, 2018. Retrieved October 17, 2018.

- Vaz 2005, pp. 14–16.

- Vaz 2005, p. 10.

- Vaz 2005, p. 16.

- Vaz 2005, pp. 16–17.

- "King Kong (1933) Notes". TCM. Archived from the original on December 16, 2019. Retrieved October 17, 2018.

- Vaz 2005, p. 167.

- Goldner & Turner 1975, p. 38.

- Vaz 2005, p. 186.

- ^ Vaz 2005, p. 194.

- Vaz 2005, p. 187.

- Van Hise 1993, p. 56.

- "Willis O'Brien giant gorilla painting". Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved August 10, 2016.

- "Willis O'Brien-Creator of the Impossible" by Don Shay, Cinefex #7, R. B. Graphics, 1982, pg. 33

- ^ Goldner & Turner 1975, p. 56.

- Goldner & Turner 1975, p. 58.

- Paul A. Woods, King Kong Cometh!, Plexus Publishing Limited, 2005, pg. 27

- Goldner & Turner 1975, p. 44.

- ^ Morton 2005, pp. 54–55.

- ^ Vaz 2005, pp. 193–194.

- Vaz 2005, p. 190.

- Morton 2005, p. 25.

- ^ Vaz 2005, p. 220.

- Goldner & Turner 1975, p. 185.

- ^ "1933 RKO Press Page Scan". Archived from the original on April 3, 2019. Retrieved April 3, 2019.

- Goldner & Turner 1975, p. 37.

- Goldner & Turner 1975, p. 159.

- Van Hise 1993, p. 66.

- Morton 2005, p. 36.

- Karen Haber, Kong Unbound, Pocket Books, 2005, pg. 106

- Morton 2005, p. 205.

- Morton 2005, p. 264.

- Weta Workshop, The World of Kong: A Natural History of Skull Island, Pocket Books, 2005

- "King Kong- Building a Shrewder Ape". Archived from the original on June 29, 2009. Retrieved April 2, 2009.

- "Kong-Sized". kongskullislandmovie.com. Archived from the original on December 15, 2017.

- warnerbroshk (March 20, 2021). "距離開戰倒數四日,先睇一睇數據 👀 究竟邊面贏面大啲呢?3月24日 世紀震撼大銀幕 2D / 3D / 4DX / D-BOX / IMAX / MX4D 同步獻映 購票即去 🔗 Link in bio #TeamKong #TeamGodzilla #GodzillaVsKong #哥斯拉大戰金剛". Instagram. Archived from the original on December 23, 2021.

- Mancuso, Vinnie (March 29, 2021). "'Godzilla vs. Kong' Tale of the Tape: Who Ya Got?". Collider. Archived from the original on February 16, 2022. Retrieved February 16, 2022.

- Franich, Darren (July 30, 2016). "Kong: Skull Island director promises 'the biggest Kong that you've seen on screen'". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on May 22, 2020. Retrieved April 20, 2020.

- Smith, C. Molly (November 11, 2016). "Kong: Skull Island unleashes exclusive first look at the movie monster'". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on June 5, 2020. Retrieved April 20, 2020.

- "Kong: Skull Island Production Notes And High-Res Photos". ScifiJapan. February 19, 2017. Archived from the original on February 18, 2017. Retrieved February 19, 2017.

- Vaz 2005, p. 277.

- Vaz 2005, p. 361.

- ^ Vaz 2005, pp. 362, 455.

- Vaz 2005, p. 362.

- ^ Vaz 2005, pp. 363, 456.

- Morton 2005, p. 150.

- ^ Vaz 2005, p. 386.

- Morton 2005, p. 158.

- ^ Vaz 2005, p. 387.

- ^ Universal City Studios, Inc. v. Nintendo Co., Ltd. 55 USLW 2152 797 F.2d 70; 230 U.S.P.Q. 409, (2nd Cir., July 15, 1986). Archived March 22, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- Morton 2005, p. 166.

- ^ Vaz 2005, p. 388.

- ^ Vaz 2005, p. 389.

- Universal City Studios v. Nintendo Co., 911 F. Supp. 578 (S.D.N.Y. December 22, 1983). "Universal City Studios v. Nintendo Co., 578 F. Supp. 911 (S.D.N.Y. 1983)". Archived from the original on October 17, 2018. Retrieved October 17, 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link). - According to Mark Cotta Vaz's book on p. 389, and citation 9 on p. 458, this quote is taken from a court summary from the document Universal City Studios, Inc. v. Nintendo Co., Ltd., 578 F. Supp. at 924.

- Second Court of Appeals, 1986, 77–8.

- Mart, Hugo (January 27, 2010). "| King Kong to rejoin Universal tours in 3-D". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on January 30, 2010. Retrieved March 4, 2010.

- "Skull Island: Reign of Kong Coming to Universal Orlando in 2016". Comingsoon.net. Archived from the original on May 9, 2015. Retrieved May 6, 2015.

- Sciretta, Peter (July 27, 2014). "Legendary Announces King Kong Prequel 'Skull Island' Movie For 2016 [Comic Con 2014]". Slashfilm.com. Archived from the original on July 28, 2014. Retrieved July 27, 2014.

- Mendelson, Scott (September 11, 2015). "What King Kong/Godzilla Switcharoo Says About Universal And Warner Bros. Priorities". Forbes. Archived from the original on November 24, 2016. Retrieved November 18, 2016.

- Graser, Marc (July 9, 2013). "Legendary Entertainment Moves to NBCUniversal (EXCLUSIVE)". Variety. Archived from the original on June 10, 2016. Retrieved November 18, 2015.

- Kit, Borys (September 10, 2015). "'Kong: Skull Island' to Move to Warner Bros. for Planned Monster Movie Universe". The Hollywood Reporter.com. Archived from the original on September 13, 2015. Retrieved September 21, 2015.

- Gill, Raymond (September 18, 2009). "Kong Rises in Melbourne". Theage.com.au. Archived from the original on March 28, 2010. Retrieved March 4, 2010.

- "King Kong live on Stage Official Website". Kingkongliveonstage.com. Archived from the original on January 10, 2016. Retrieved March 4, 2010.

- Hetrick, Adam. "King Kong Sets Broadway Opening Night" Archived November 9, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, Playbill.com, November 8, 2017

- "Robotic King Kong to star in stage musical". CBC News. September 16, 2010. Archived from the original on September 19, 2010. Retrieved September 17, 2010.

- "Asmus & Magno Take a Monstrous Trip with 'Kong of Skull Island'". Comic Book Resources. April 8, 2016. Archived from the original on April 9, 2016. Retrieved April 8, 2016.

- "THE ULTIMATE RUMBLE IN THE JUNGLE!: King Kong Vs. Tarzan Arrives This Summer!". Forces of Geek. March 9, 2016. Archived from the original on March 10, 2016. Retrieved March 9, 2016.

- "Kong On The Planet Of The Apes: Exclusive First Look At The Comic Mini-Series". Empire. August 9, 2017. Archived from the original on August 9, 2017. Retrieved November 8, 2017.

- "Soda Pop Labels of Fame". Archived from the original on April 3, 2018. Retrieved April 3, 2018.

- "'King Kong Skull Island' TV Series in the Works". TheHollywoodReporter. April 18, 2017. Archived from the original on April 21, 2017. Retrieved April 21, 2017.

- "NFTNT to Create NFT Trading Cards for King Kong of Skull Island". Dimensional Branding Group. Archived from the original on April 13, 2022. Retrieved April 13, 2022.

- "King Kong of Skull Island adds Dynamite Entertainment as Games & Comics Licensee". Dimensional Branding Group. Archived from the original on April 13, 2022. Retrieved April 13, 2022.

- "Raw Thrills – February 2021". February 2021. Archived from the original on February 27, 2021. Retrieved April 13, 2022.

- "Classic King Kong Model Kits". Dimensional Branding Group. Archived from the original on May 31, 2022. Retrieved April 13, 2022.

- "DEVITO ARTWORKS TEAMS UP WITH GAMEMILL ENTERTAINMENT". Licensing Magazine. December 20, 2022. Retrieved October 19, 2023.

- Cullins, Ashley (April 28, 2016). "Legendary, Warner Bros. Sued for Allegedly Stealing 'Kong: Skull Island' Story". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on May 2, 2016. Retrieved May 9, 2016.

- Johnston, Rich (July 20, 2022). "Dynamite Grabs King Kong of Skull Island License From Boom & Legendary". BleedingCool. Retrieved May 15, 2023.

- "King Kong: The Great War at The Grand Comics Database".

- Andreeva, Nellie (August 23, 2022). "'King Kong' Live-Action Series In Works At Disney+ From Stephany Folsom, James Wan's Atomic Monster & Disney Branded TV". Deadline. Archived from the original on August 23, 2022. Retrieved August 24, 2022.

- Davids, Brian (March 30, 2021). "Why 'Godzilla vs. Kong' Director Adam Wingard Treated Kong Like an '80s Action Hero". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on April 19, 2021. Retrieved April 19, 2021.

- Pearson, Ben (March 25, 2021). "Adam Wingard Was Hand-Picked to Direct 2005 King Kong Sequel". SlashFilm.com. Archived from the original on March 18, 2022. Retrieved March 17, 2022.

- Morton 2005, pp. 239, 241.

- "King Kong Stats Page". Archived from the original on June 29, 2009. Retrieved May 3, 2009.

- "King Kong". Archived from the original on May 16, 2008. Retrieved November 14, 2008.

- "King Kong (2nd Generation)". Archived from the original on May 16, 2008. Retrieved November 14, 2008.

- "Lost Project: Operation Robinson Crusoe: King Kong vs. Ebirah". Toho Kingdom. Archived from the original on June 26, 2014. Retrieved October 16, 2014.

- Ryfle 1998, p. 135.

- Ito, Richard (March 30, 2021). "When King Kong Accidentally Met Godzilla". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 31, 2021. Retrieved March 31, 2021.

- "Ryuhei Ktamura & Shogo Tomiyama interview - Godzilla Final Wars premiere - PennyBlood.com". February 3, 2005. Archived from the original on February 3, 2005. Retrieved May 30, 2021.

- ^ "AFI Catalog - King Kong (1933)". American Film Institute. Archived from the original on May 8, 2023. Retrieved May 7, 2023.

- ^ "King Kong vs. Godzilla (1963)". The Criterion Collection. Archived from the original on May 8, 2023. Retrieved May 7, 2023.

- ^ Ryfle 1998, p. 79.

- Parlevliet, Mirko (August 25, 2022). "Godzilla vs Kong Sequel Starts Filming". Vital Thrills. Archived from the original on April 19, 2023. Retrieved August 25, 2022.

- ^ "Origins". Writers Guild of America West. Retrieved April 26, 2023.

- Zorilla, Monica (January 27, 2021). "Netflix Expands its Growing Anime Repertoire with 'Skull Island' and 'Tomb Raider' Adaptations". Variety. Archived from the original on January 27, 2021. Retrieved January 27, 2021.

- Andreeva, Nellie (August 23, 2022). "'King Kong' Live-Action Series In Works At Disney+ From Stephany Folsom, James Wan's Atomic Monster & Disney Branded TV". Deadline. Archived from the original on August 23, 2022. Retrieved August 24, 2022.

- National broadcast list. Animage. Tokuma Shoten. October 1981. pp.100-101

- Northrup, Ryan (January 12, 2024). "Monarch Season 1 Ending & Surprise Cameo Explained By Creators". Screenrant. Retrieved January 30, 2024.

- Hinsley, F. H.; Simkins, C. A. G. (1990). British Intelligence in the Second World War: Volume 4, Security and Counter-Intelligence. Cambridge University Press. p. 373.

- "AllMusic". AllMusic. Archived from the original on June 28, 2015. Retrieved August 20, 2013.

- Sleeve notes, Waterloo re-issue, Carl Magnus Palm, 2014

General and cited sources

- Erb, Cynthia Marie, 1998, Tracking King Kong: A Hollywood Icon in World Culture, Wayne State University Press, ISBN 0-8143-2686-2.

- Affeldt, Stefanie (2015). "Exterminating the Brute: Racism and Sexism in 'King Kong'". In Hund, Wulf D.; Mills, Charles W.; Sebastiani, Silvia (eds.). Simianization: Apes, Class, Gender, and Race. Racism Analysis Yearbook 6. Berlin: Lit Verlag. ISBN 978-3-643-90716-5.

- Goldner, Orville; Turner, George E. (1975). The Making of King Kong: The Story Behind a Film Classic. A. S Barnes and Co.

- Morton, Ray (2005). King Kong: The History of a Movie Icon. Applause Theater and Cinema Books. ISBN 1557836698.

- Ryfle, Steve (1998). Japan's Favorite Mon-Star: The Unauthorized Biography of the Big G. ECW Press. ISBN 1-55022-348-8.

- Van Hise, James (1993). Hot Blooded Dinosaur Movies. Pioneer Books.

- Vaz, Mark Cotta (2005). Living Dangerously: The Adventures of Merian C. Cooper, Creator of King Kong. Villard. ISBN 1-4000-6276-4.

External links

- The 1933 film King Kong at IMDb

- Official King Kong movies website

- The 2005 remake King Kong at IMDb

- King Kong series listing at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

| Godzilla | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Monsterverse | |

|---|---|

| Films |

|

| Television |

|

| Soundtracks | |

| Monsters | |

| Related | |

- King Kong (franchise)

- King Kong (franchise) characters

- Godzilla characters

- Monsterverse characters

- Film characters introduced in 1933

- Fantasy film characters

- Science fiction film characters

- Kaiju

- Animal superheroes

- Animal supervillains

- Animated characters

- Fictional apes

- Fictional axefighters

- Fictional characters with superhuman strength

- Fictional giants

- Fictional gorillas

- Fictional mass murderers

- Fictional monsters

- Fictional prehistoric animals