This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

| Kingdom of TahitiBasileia no Tahiti (Tahitian) Royaume de Tahiti (French) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1788/91–1880 | |||||||||

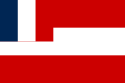

Top: 1788–1843

Top: 1788–1843Bottom: 1843–1880  Coat of arms

Coat of arms

| |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Status | Independent Kingdom (1788/91–1842) French Protectorate (1842–1880) | ||||||||

| Capital | Papeete (from 1847) | ||||||||

| Common languages | |||||||||

| Religion | Tahitian, Christianity | ||||||||

| Government | Absolute monarchy | ||||||||

| Monarch | |||||||||

| • 1788/91–1803 | Pōmare I (first) | ||||||||

| • 1877–1880 | Pōmare V (last) | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

| • Founded by Pōmare I | 1788/91 | ||||||||

| • Consolidated power after Battle of Te Feipī | 12 November 1815 | ||||||||

| • Establishment of the French protectorate | 9 September 1842 | ||||||||

| • French-Tahitian War | 1843–1847 | ||||||||

| • French protectorate | 1 January 1847 | ||||||||

| • Annexation by France and dissolution | 29 June 1880 | ||||||||

| Currency | French franc Pound sterling | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | French Polynesia | ||||||||

The Kingdom of Tahiti or the Tahitian Kingdom was a Polynesian monarchy founded by paramount chief Pōmare I, who, with the aid of British missionaries and traders, and European weaponry, unified the islands of Tahiti, Moʻorea, Teti‘aroa, and Mehetiʻa. The kingdom eventually annexed the Tuamotus, and the Austral Islands (Rapa Iti, Rurutu, Rimatara, Tubuai, Raivavae).

Its leaders were Christian following the baptism of Pomare II. Its progressive rise and recognition by Europeans allowed Tahiti to remain free from a planned Spanish colonization as well as other European claims to the islands.

The kingdom was one of a number of independent Polynesian states in Oceania, alongside Ra'iātea, Huahine, Bora Bora, Hawai‘i, Samoa, Tonga, Rarotonga and Niue in the 19th century. The kingdom is known for bringing a period of peace and cultural and economic prosperity to the islands over the reign of the five Tahitian monarchs. Tahiti and its dependencies transformed into French protectorates in 1842 and largely annexed as a colony of France in 1880 after Pomare V was convinced to give Tahiti and its dependencies to France. The monarchy was therefore abolished shortly after the annexation, though there are still pretenders.

History

Beginning

Pōmare I was born at Pare, ca. 1743. He was the second son of Teu Tunuieaiteatua by his wife, Tetupaia-i-Hauiri. He initially reigned under the regency of his father. He succeeded on the death of his father as Ariʻi-rahi of Porionuʻu 23 November 1802.

In terms of European influence in the period immediately encompassing the period of Pomare I.

"The attempt at colonization by the Spaniards in 1774 was followed by the settlement of thirty persons brought in 1797 by the missionary ship Duff. Though befriended by Pomare I (who lived until 1805), they had many difficulties, especially from the constant wars, and at length they fled with Pomare II to Eimeo and ultimately to New South Wales. They returned in 1812 when Pomare renounced heathenism."

Pomare was the Tahitian chieftain on good terms with the British. The additional British captains arriving at Tahiti accepted his claim to hegemony. They gave him guns in trade and helped him in his battles. Captain James Cook gave him the advantage in a number of battles with rival forces during his last stay in Tahiti, circa 1777. British missionaries arrived, sent by a non-denominational Protestant group called the London Missionary Society. Pomare befriended the missionaries, and the missionaries favored both peace and Pomare, but, with the British unwilling to send concrete aid to assist Pomare in his attempts to create order among the islands, the missionaries were unable to stop the warring.

As king, Pōmare I succeeded in uniting the different chiefdoms of Tahiti into a single kingdom, composed of the islands of Tahiti itself, Moʻorea, Mehetiʻa, and the Tetiʻaroa group. His service as the first king of unified Tahiti ended when he abdicated in 1791, but he remained the regent of Tahiti from 1791 until 1803. He married four times and had two sons and three daughters.

By now, islanders were passing to each other diseases that had arrived with the Europeans: diseases for which they had not developed immunity. Many islanders were dying. In 1803, Pomare died. His son, Otu, became head of the family, with the title Pomare II. Tū Tūnuiʻēʻaiteatua Pōmare II reigned 1803–1821. The missionaries remained allied with the Pomare family. Despite their pacifism, they wanted to see Pomare II successful in uniting the islanders under his rule.

Consolidation

Pomare II

Pōmare II, King of Tahiti (1774 – 7 December 1821) was the second king of Tahiti between 1782 and 1821. He was installed by his father Pōmare I at Tarahoi, 13 February 1791. He ruled under regency from 1782 to 1803.

Initially recognised as supreme sovereign and Ariʻi-maro-ʻura by the ruler of Huahine, he was subsequently forced to take refuge in Moʻorea 22 December 1808, but returned and defeated his enemies at the Battle of Te Feipī. He was thereafter recognized as undisputed King of Tahiti, Moʻorea and its dependencies.

Other chieftains on Tahiti became fed up with what they saw as Pomare's pretensions of power, and in 1808 they drove him from Tahiti to the nearby island of Eimeo (Moorea). These other chieftains hostile towards the missionaries, which caused the missionaries to leave Tahiti for other islands.

Pomare organized military support from his kinsmen on the islands of Raiatea, Bora Bora and Huahine. Warring resumed, with Pomare winning the decisive Battle of Te Fe’i Pī, on 12 November 1815. His victory was a victory also for the Christians. And, in victory Pomare surprised the Tahitians. He pardoned all who laid down their weapons. When defeated warriors returned from the hills, they found their homes had not been set afire and that their wives and children had not been slaughtered. The warfare culture of the islanders had been changed by the influence that the missionaries had on Pomare II.

Centralized authority among chiefs was not traditional in Tahiti, but the missionaries welcomed Pomare's new power. Distress from disease, civil war and death won for them serious attention to their teachings. They launched a campaign to teach the islanders to read, so they could read scripture. There were mass conversions in hope of the supernatural protections that Christianity offered. The missionaries told the islanders how to dress. The climate was suitable to exposing the skin to the greater cool of open air, but for the missionaries the temperature was of no consideration. Wearing full clothing for them was preferable to wearing little to none.

Another lifestyle promoted by the missionaries was manufacturing, the missionaries setting up a sugar refinery and a textile factory. In 1817, Tahiti acquired its first printing press, and, in 1819, cotton, sugar and coffee crops were planted.

Pomare II asked the missionaries for advice on laws, and the missionaries, being monarchists and wanting Pomare to be a proper monarch, advised him that the laws would have to be his, not theirs. They did make suggestions, however, and in September 1819, Pomare produced Tahiti's first written law. There was protection of life and property, observance of Sabbath, a sanctification of marriage and a judiciary to maintain the laws.

Pōmare was married to Queen Tetua-nui Taro-vahine.

He was baptised 16 May 1819 at the Royal Chapel, Papeʻete. Three London Missionary Society missionaries, Henry Bicknell, William Henry, and Charles Wilson preached at the baptism of King Pomare II.

Pomare died of drink-related causes at Motu Uta, Papeete, 7 December 1821. Pomare II died in 1824 at the age of forty-two, leaving behind an eight-year-old daughter and a five-year-old son. The son, Teriʻi-ta-ria and Pōmare III, ruled in name from 1821 to 1827 while being educated by the missionaries. He died in 1827 of an unknown disease, and the daughter, then eleven, became Queen Pōmare IV.

Pomare III

Pōmare III was the king of Tahiti between 1821 and 1827. He was the second son of Pōmare II.

He was born at Papaʻoa, ʻArue, 25 June 1820 as Teri'i-ta-ria, and was baptised on 10 September 1820. He succeeded to the throne on the death of his father. He was crowned at Papaʻoa, ʻArue, 21 April 1824.

Pomare III's education took place at the South Sea Academy, Papetoai, Moʻorea. He reigned under a council of Regency until his death 8 January 1827. During his reign, the Kingdom's first flag was adopted.

He was succeeded by his sister, ʻAimata Pōmare IV Vahine-o-Punuateraʻitua, who reigned 1827–1877.

Pōmare IV

Pōmare IV, Queen of Tahiti (28 February 1813 – 17 September 1877), more properly ʻAimata Pōmare IV Vahine-o-Punuateraʻitua (otherwise known as ʻAimata {meaning: eye-eater, after an old custom of the ruler to eat the eye of the defeated foe} or simply as Pōmare IV), was the queen of Tahiti between 1827 and 1877.

She was the daughter of Pōmare II. She succeeded as ruler of Tahiti after the death of her brother Pōmare III when she was only 14 years old.

She succeeded in reuniting Raʻiatea and Porapora (Borabora) with the kingdom of Tahiti. She hosted numerous Britons, including Charles Darwin.

Return of the Pitcairn Islanders

By 1829, of those who had arrived at Pitcairn on HMS Bounty in 1790, only seven remained, but with their offspring they numbered 86. The supply of timber on Pitcairn was decreasing and the availability of water was erratic.

Since the end of the Napoleonic Wars, the Pitcairn islanders had been discovered by and had friendly contact with the Royal Navy and British authorities. In 1830, Tahiti's Queen Pomare IV invited the Pitcairners to return to Tahiti, and in March 1831, a British ship transported them there. The Tahitians welcomed the Pitcairners and offered them land. But having been isolated and not having developed any immunity to the diseases now on Tahiti, the Pitcairners suffered from disease in alarming number. Fourteen of them died. The Tahitians took up a collection for the surviving Pitcairners, and for $500 a whaling captain took them back to Pitcairn.

French Protectorate

Main article: Franco-Tahitian War (1844–47)

In 1842, a European crisis involving Morocco escalated between France and Great Britain when Admiral Abel Aubert du Petit-Thouars, acting independently of the French government, convinced Tahiti's Queen Pomare IV to accept a French protectorate. George Pritchard, a Birmingham-born missionary and acting British Consul, had been away at the time. However he returned to work towards influencing the locals against the influence of the Catholic French. In November 1843, Dupetit-Thouars (again on his own initiative) landed sailors on the island, annexing it to France. He then threw Pritchard into prison, subsequently sending him back to Britain.

During this time, Thouars managed to convince Pomare IV to sign to putting her country under the protection of France, although he was not empowered to do so, nor was he ever sanctioned in this regard. News of Tahiti reached Europe in early 1844. The French statesman François Guizot, supported by King Louis-Philippe of France, had denounced annexation of the island, and the treaty was never ratified by France.

However, the French did have an interest in the region, and the treaty was enforced from its signing by various factions. The Franco-Tahitian War between the Tahitians and French went from 1843 to 1847. Pomare IV ruled under French administration from 1843 until 1877.

While the Dynasty retained their title for some time, they lost outright control of their country.

Death of Pomare IV

Pomare IV died from natural causes in 1877. She is buried in the Royal Mausoleum, Papaʻoa, ʻArue. She was succeeded by Pōmare V, who reigned 1877–1880.

Pomare V and forced abdication

Pōmare V, King of Tahiti (3 November 1839 – 12 June 1891) was the last king of Tahiti, reigning from 1877 until his forced abdication in 1880. He was the son of Queen Pōmare IV. He was born as Teri'i Tari'a Te-rā-tane and became Heir Apparent and Crown Prince (Ari'i-aue) upon the death of his elder brother on 13 May 1855. He became king of Tahiti on the death of his mother on 17 September 1877. His coronation was on 24 September 1877 at Pape'ete.

He married twice, first on 11 November 1857 to Te-mā-ri'i-Ma'i-hara Te-uhe-a-Te-uru-ra'i, princess of Huahine. He divorced her on 5 August 1861. His second marriage was to Joanna Mara'u-Ta'aroa Te-pa'u Salmon (thereafter known as Her Majesty The Queen Marau of Tahiti), at Pape'ete on 28 January 1875. He divorced her on 25 January 1888.

Pomare V had one son and two daughters.

The island of Tahiti and most of its satellites remained a French protectorate until the late 19th century, when King Pomare V (1842–1891) was forced to cede the sovereignty of Tahiti and its dependencies to France. On 29 June 1880, he gave Tahiti and its dependencies to France, whereupon he was given a pension by French government and the titular position of Officer of the Orders of the Legion of Honour and Agricultural Merit of France, on 9 November 1880.

He died from alcoholism at the Royal Palace, Pape'ete, and is buried at the Tomb of the King, Utu'ai'ai in 'Arue.

Impact

The Dynasty left an indelible mark on Tahitian and surrounding cultures. At their height of power, the Pomares' managed to rule effectively from their base in Tahiti and Mo'orea a kingdom of islands spread over 3 million km of sea and had diplomatic relations and influences from the Cook Islands to Rapa Nui. They experienced, and were indeed a part and product of the European Age of Exploration in the Pacific. They produced an unprecedented period of cultural ascendancy in Tahiti, and saw their people through a period of change, and foreign influence and wars. They both preserved traditions and independence for a time, while also serving as a conduit for suppression of culture and resigned to French demands, facilitating the subsequent colonization of Tahiti by France.

Monarchs of Tahiti (1791–1880)

Main articles: List of monarchs of Tahiti and Pōmare dynastyCurrent status

As of February 2009, Tauatomo Mairau claimed to be the heir to the Tahitian throne, and attempted to re-assert the status of the monarchy in court. His claims were not recognised by France.

In 2010, he became pretender to the throne and claimed the title Prince Marau of Tahiti. He was working to have royal trust lands returned to him and his family. The French government mortgaged the land after World War II, and in doing so violated the terms of the agreement signed with Pomare V in 1880 which reserved control of the trust lands for the royal family of Tahiti. The banks may be in the process of freezing the assets, and Mairau sued to prevent native Tahitians from being evicted from his trust lands, and wished for them to retain their usage rights over the land. He died in May 2013.

On 28 May 2009, Joinville Pomare, an adopted member of the Pomare family, declared himself King Pomare XI, during a ceremony attended by descendants of leading chiefs but spurned by members of his own family. Other members of the family recognise his uncle, Léopold Pomare, as heir to the throne.

Notable Tahitians

Royalty and chieftains

- Pōmare I, King of Tahiti.

- Pōmare II, King of Tahiti.

- Teriʻitoʻoterai Teremoemoe, Queen-Regent of Tahiti.

- Teriʻitaria Ariʻipaeavahine, Queen-Regent of Tahiti, Queen regnant of Huahine.

- Pōmare III, King of Tahiti.

- Pōmare IV, Queen regnant of Tahiti.

- Ariʻifaʻaite, Prince consort of Tahiti.

- Pōmare V, King of Tahiti.

- Marau Salmon, Queen consort of Tahiti.

- Tamatoa V, Prince of Tahiti, later King of Raiatea.

- Teriʻiourumaona, Princess of Tahiti and Raiatea, designated heir as Pōmare VI.

- Teriʻivaetua, Princess of Tahiti and Raiatea, heiress presumptive of her uncle.

- Teriʻimaevarua III, Princess of Tahiti and Raiatea, later Queen of Bora Bora.

- Teriʻitapunui Pōmare, Prince of Tahiti.

- Teriʻitua Tuavira Pōmare, Prince of Tahiti.

- Hinoi Pōmare, Prince of Tahiti.

- Tati the Great, head chieftain of the Teva clan of Pare district, counselor to Pōmare III and Pōmare IV.

- Ariʻitaimai, head chiefess of the Teva clan of Pare district.

- Titaua Salmon Brander, daughter of Ariʻitaimai.

- Moetia Salmon Atwater, daughter of Ariʻitaimai.

- Tute Tehuiariʻi, Tahitian chief and missionary.

- Mauli Tehuiariʻi, Tahitian chiefess who married into Hawaiian nobility.

- Manaiula Tehuiariʻi Sumner, Tahitian chiefess who married into Hawaiian nobility.

- Ninito Teraiapo Sumner, Tahitian chiefess who married into Hawaiian nobility.

Others

- William Ellis, missionary.

- George Pritchard, missionary.

- Alexander Salmon Sr., Secretary of Pōmare IV, father of Queen Marau.

- Alexander Ariʻipaea Salmon Jr., Businessman and adventurer, brother of Queen Marau.

See also

References

- "The Tahitian Royal Family". Retrieved 26 August 2011.

- "History of French Polynesia". Archived from the original on 26 September 2011. Retrieved 26 August 2011.

- Henry, Teuira (1993). Mythes Tahitiens (in French) (L’Aube des Peuples ed.). Paris: Gallimard (published 2016). pp. 201–219. ISBN 978-2-07-073297-5.

- Henry, Teuira (2004). Tahiti aux temps anciens, Généalogies Royales de Tahiti (in French). Paris: Société des Océanistes. pp. 255–281. ISBN 978-2-85430-014-7.

- "HM Queen Pomare IV (Aimata)". Ancestry.com. Archived from the original on 3 November 2012. Retrieved 7 September 2011.

- "Return of the Pitcairn Islanders". Retrieved 7 June 2011.

- "How Tahiti Became French A Sectarian War Destroyed Pomare's Throne". Pacific Islands Monthly. Vol. XXXI, no. 2. 1 September 1960. pp. 84–86. Retrieved 19 December 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- "Tahitian royal forms government". Radio New Zealand International. 22 January 2006. Retrieved 13 October 2011.

- "Tahitian land activist claims France disregards 19th century treaties". Radio New Zealand International. 3 February 2009. Retrieved 13 October 2011.

- "New republic of Hau Pakumotu is the world's newest country". Archived from the original on 10 November 2012. Retrieved 5 September 2011.

- "King' Mairau forged links between Tahiti and Cooks". King' Mairau forges links between Tahiti and Cooks. 17 March 2010. Archived from the original on 8 March 2012. Retrieved 9 June 2011.

- "Royal ceremony held in Tahiti". RNZ. 1 June 2009. Retrieved 25 June 2022.

- "Joinville, l’homme qui voulait être roi… " Archived 5 September 2012 at archive.today, La Dépèche de Tahiti, 29 May 2009

Further reading

- Gonschor, Lorenz Rudolf (August 2008). Law as a Tool of Oppression and Liberation: Institutional Histories and Perspectives on Political Independence in Hawaiʻi, Tahiti Nui/French Polynesia and Rapa Nui (PDF) (MA thesis). Honolulu: University of Hawaii at Manoa. hdl:10125/20375. OCLC 798846333. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 January 2020. Retrieved 29 December 2019.

External links

![]() Media related to Kingdom of Tahiti at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Kingdom of Tahiti at Wikimedia Commons

| French Polynesia articles | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| History |  | ||

| Geography | |||

| Politics | |||

| Economy | |||

| Culture | |||