| The examples and perspective in this article may not represent a worldwide view of the subject. You may improve this article, discuss the issue on the talk page, or create a new article, as appropriate. (September 2007) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

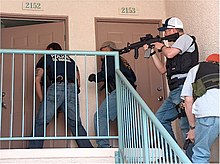

Knock-and-announce, in United States law criminal procedure, is an ancient common law principle, incorporated into the Fourth Amendment, which requires law enforcement officers to announce their presence and provide residents with an opportunity to open the door prior to a search.

The rule is currently codified in the United States Code, which governs Fourth Amendment searches conducted by the federal government. Most states have similarly codified the rule into their own statutes, and remain free to interpret or augment the rule and its consequences in any fashion that remains consistent with Fourth Amendment principles. A state's knock-and-announce rule will govern searches by state actors pursuant to state-issued warrants, assuming that Federal actors are not extensively involved in the search.

The rule

English common law has required law enforcement to knock-and-announce since at least Semayne's case (1604). In Miller v. United States (1958), the Supreme Court of the United States recognized that police must give notice before making a forced entry, and in Ker v. California (1963) a divided Court found that this limitation had been extended against the states by the United States Constitution.

However, in Wilson v. Arkansas (1995) the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that a knock-and-announce before entry was a factor that must be considered in reviewing the overall constitutionality of a Fourth Amendment search. After several state attempts to exclude specific categories (e.g. drug crimes) from the knock-and-announce rule, the Supreme Court in Richards v. Wisconsin prohibited the policy, and demanded a return to a case-by-case review scenario. The Richards Court suggested that the knock and announce rule could be dispensed with only in certain circumstances, for example where police have reasonable suspicion that an exigent circumstance exists. The Court read its earlier Wilson opinion to suggest that such circumstances might include those:

- which present a threat of physical violence

- where there is "reason to believe that evidence would likely be destroyed if advance notice were given"

- where knocking and announcing would be dangerous or "futile"

The Court expressly stated that whether reasonable suspicion exists depends in no way on whether police must destroy property in order to enter.

In a similar manner, where officers reasonably believe that exigent circumstances, such as the destruction of evidence or danger to officers will exist, a no-knock warrant may be issued. However, despite police awareness that such future exigencies will exist, they are generally not required to seek such a warrant; in this case, police must have an objectively reasonable belief, at the time of executing the warrant, that such circumstances do in fact exist.

The Supreme Court has given some guidance as to how long officers must wait after knocking and announcing their presence before entry may be made. In U.S. v. Banks, the Supreme Court found 15 to 20 seconds to be a reasonable time where officers received no response after knocking and where officers feared the home occupant may be destroying the drug evidence targeted by the search warrant. As with most other things in the Fourth Amendment arena, the Court left reasonableness of the time period to be determined based on the totality of the circumstances; and thus inferior Federal courts have found even shorter time periods to be reasonable. Some different factors have been propounded by lower courts to guide the analysis of a reasonable wait period. A few examples are:

- the size, design, and layout of the premises

- the time of day the search is being executed

- the nature of the suspected offense (in particular, does it involve evidence easily destroyed? Is the suspect dangerous?)

- the evidence demonstrating guilt.

Federal courts also recognize that consent may vitiate part or all of the rule. For example, where officers knock, but before announcement are invited in, they no longer need to announce.

Effects of the rule

In Hudson v. Michigan (2006), the divided Supreme Court ruled that a violation of the knock-and-announce rule does not require the suppression of evidence using the exclusionary rule. That is primarily because the goals served by a knock-and-announce policy tend to be lesser than other requirements, such as the warrant requirement, of a valid Fourth Amendment search, but the latter is to protect a reasonable expectation of privacy in a person's body, papers, and effects (among other things), the knock-and-announce rule is designed only to provide a brief moment of privacy for an individual to compose themself before a valid search occurs, to prevent an individual from mistakenly believing that police are common intruders and thus endangering them and to prevent property damage from a forcible entry. Because police with probable cause and a valid warrant are already entitled to an entry and search, violation of the simple knock-and-announce rule has not been deemed grave enough in the federal courts or in most states to justify suppression of the evidence.

Most states have composed their own statutes, which require a knock and announcement before making a warranted entry. Because the states are free to offer more liberty to criminal defendants than the Federal Constitution, the states remain free to impose the exclusionary rule for a violation of the knock-and-announce rule. The Supreme Court opinion in Hudson is necessarily binding only on searches conducted by the federal government.

In popular culture

In July 2020, the podcast Criminal released an episode called "Knock and Announce" about the 2015 police raid on Julian Betton's apartment in Myrtle Beach, South Carolina.

See also

- No-knock warrant

- Fourth Amendment to the United States Constitution

- Semayne's case

- Sneak and peek warrant

References

- Wilson v. Arkansas, 514 U.S. 927 (1995); Richards v. Wisconsin, 520 U.S. 385 (1997)

- 18 U.S.C. § 3109.

- See, e.g., Washington Code Annotated 10.31.040.

- U.S. v. Scroggins, 361 F.3rd 1075 (8th Cir. 2004)

- G. Robert Blakey (1964). "The Rule of Announcement and Unlawful Entry: Miller v. United States and Ker v. California". University of Pennsylvania Law Review. 112 (4): 499–562. doi:10.2307/3310634. JSTOR 3310634. Retrieved 23 March 2017.

- Kevin Sack (19 March 2017). "Door-Busting Raids Leave Trail of Blood - The Heavy Toll of Using SWAT Teams for Search Warrants". The New York Times. p. A1. Retrieved 21 March 2017.

- 514 U.S. 927 (1995)

- 520 U.S. 385 (1997)

- U.S. v. Ramireèz, 523 U.S. 65 (1998).

- Memorandum Opinion for the Chief Counsel, Drug Enforcement Administration, from Patrick F. Philbin, Deputy Assistant Attorney General for the Office of Legal Counsel, Re: Authority of Federal Judges and Magistrates to Issue "No-Knock" Warrants, 26 Op. O.L.C. 44 (June 12, 2002).

- See, e.g., U.S. v. Segura-Baltazar 448 F.3rd 1281, (11th Cir. 2006)

- See, e.g., U.S. v. Musa, 401 F.3d 1208 (10th Cir. 2005)

- U.S. v. Maden, 64 F.3rd 1505 (10th Cir. 1995)

- 540 U.S. 31 (2003)

- U.S. v. Jenkins, 175 F.3d 1208, 1213 (10th Cir. 1999) (stating the Supreme Court has not established a clear cut standard to determine the amount of time officers must wait).

- See, e.g., U.S. v. Cline, 349 F.3d 1276 (10th Cir. 2003)

- U.S. v. Chavez-Miranda, 306 F.3rd 973 (9th Cir. 2002)

- U.S. v. Hatfield, 365 F.3d 332 (4th Cir. 2004)

- U.S. v. Banks, 282 F.3d 699 (9th Cir. 2002)

- "Knock and Announce". Criminal. July 3, 2020.

| Criminal procedure (investigation) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Criminal investigation | ||

| Criminal prosecution | ||

| Charges and pleas | ||

| Related areas | ||