| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Konrad Mägi" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (January 2022) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

| Konrad Mägi | |

|---|---|

Konrad Mägi (photo c. 1898–1905) Konrad Mägi (photo c. 1898–1905) | |

| Born | Konrad Vilhelm Mägi (1878-11-01)1 November 1878 Hellenurme Manor, Elva Parish, Governorate of Livonia |

| Died | 15 August 1925(1925-08-15) (aged 46) Tartu, Estonia |

| Nationality | Estonian |

| Movement | Expressionism |

Konrad Vilhelm Mägi (1 November 1878 – 15 August 1925) was one of the first modernist painters in Estonia and the Nordic countries, at the core of whose creative legacy are visionary landscapes. He only worked for sixteen years, yet the total volume of his oeuvre is estimated to be around 400 paintings.

Numerous exhibitions of his works have been held in Estonia, and in recent years, his art has been discovered in Europe: in 2017, there was a solo exhibition of Konrad Mägi’s paintings in the Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Moderna in Rome; in 2018, his works were displayed at the exhibition Wild Souls: Symbolism in the Art Of the Baltic States in the Orsay Museum; in 2021, more than a hundred of Mägi’s works were exhibited in the EMMA Museum in Espoo, and in 2022, the same works were displayed in the Lillehammer Art Museum.

Konrad Mägi’s works are particularly appreciated for their vigorous and impulsive colours and a pantheistic approach to nature, making him unique in European early-20th-century modernism. Mägi worked in different parts of Europe, according to which his oeuvre is divided into rather dissimilar chapters: Denmark, Norway, France, the island of Saaremaa, southern Estonia, Italy etc.

The reception of his art went through various periods, too. In the 1920s and 1930s, Konrad Mägi’s oeuvre influenced a large part of Estonian art created at the time. During World War II, his art was condemned (the Soviet authorities ordered his works to be removed from exhibitions, his letters to be destroyed, etc.); it continued to be forbidden until the second half of the 1950s. Towards the end of the 1950s, as political austerity relaxed, Mägi’s oeuvre was “re-introduced” and several retrospectives were held.

Despite the fact that Mägi spent the majority of his life in towns, his oeuvre mainly revolves around landscapes: environments lacking humans, where nature offers irrational, mystical, metaphysical and religious experiences. Konrad Mägi’s oeuvre is rooted in existential tensions that made him yearn for other potential worlds. As a young man he took actively part in the revolutionary movement, but later withdrew completely from politics and focussed entirely on art. “Happiness is not for us, sons of a poor land,” Mägi once wrote. “For us, art is the only way out, because when the soul is filled with the eternal suffering of life, art will provide what life cannot give us. There, in art, in one’s own oeuvre, can one find peace.”

In addition to landscape paintings, Mägi painted portraits (including several portraits of members of the women’s movement) and still-lifes. He was the first director of Pallas, the first Estonian higher art school.

Konrad Mägi’s health seriously troubled him throughout his creative career: various illnesses led to a rapid deterioration of his health in the 1920s. Konrad Mägi was only 46 years old when he died. The whereabouts of more than half of his works are still unknown.

Biography

Childhood

Konrad Mägi was born on 1 November 1878 in southern Estonia. He spent his childhood in the small village of Uderna near Elva, which was surrounded by large virgin forests and had a big railway line passing through it. His father, Andres Mägi, was a comparatively well-to-do estate manager, who took actively part in the Estonian national awakening movement in the second half of the 19th century. Practically nothing is known about Konrad Mägi’s mother, Leena Mägi. Konrad Mägi was the youngest child in the family: he had four older brothers and an older sister; another older brother had died as a child. The first name Konrad was possibly chosen because German names were popular among the Estonian rural population at the time. In Uderna, he attended the local elementary school for barely a few months.

Something must have happened to Andres Mägi’s mental health: he began changing jobs increasingly often. That led to the dissolution of the family: at the age of 11, Konrad Mägi moved to Tartu with his mother and sister. In the autumn of 1890, Konrad Mägi began to study at the three-year elementary school of the Tartu Apostolic Orthodox Church, which he quit after only a couple of months. A few years later, he enrolled in the Municipal School of Tartu, but never finished his studies there either. Instead, he became a carpenter’s apprentice at the local furniture factory. A few furniture designs from that period have survived.

Discovering Art

In 19th-century Estonia, fine arts were something that mainly Baltic-Germans had access to. The indigenous rural population did not see much art, not to mention creating it. Nevertheless, towards the end of the century, various cultural activities emerged, including an interest in art. Konrad Mägi and his friends became actively engaged in physical culture and sports, but were also interested in theatre, literature, philosophy and classical music.

In 1897, Konrad Mägi was employed by the Bandelier Furniture Factory, where he was entrusted with making complicated rosettes and volutes. Because of the factory owners’ wish to improve the quality of their products, Mägi and other employees were enrolled in Rudolf von zur Mühlen’s drawing classes. There, Mägi studied perspective drawing as well as technical drawing and possibly had his first encounters with painting. In 1902, Mägi decided to go and study art at the Stieglitz School of Technical Drawing in St. Petersburg.

Travels

St. Petersburg

Konrad Mägi arrived in Saint Petersburg in January 1903 to study sculpture under Amandus Adamson at the Stieglitz school. His studies were successful, and he met several other Estonians aiming to become artists, including Nikolai Triik. Nevertheless, he was not happy with the technical and rather dry approach to drawing at Stieglitz. When sculpture department was shut down a while later, Mägi gradually lost his interest in studies. He is known to have actively visited museums and to have been most of all fascinated by the works of Mikhail Vrubel and Nicholas Roerich.

When the revolution of 1905 broke out, Mägi participated in the events: he is said to have organised several provocations in churches and even to have aided revolutionaries in caching their weapons.

Mägi collaborated with several political publications in Estonia by sending them satirical illustrations with a symbolic undertone. There was a student strike also in the Stieglitz school, and one of the organisers may have been Mägi. He refused to continue his studies in a backward school and was dismissed. He went on to study in the studio of Jakob Goldblatt and also began to teach art lessons, but in April 1906 he left St. Petersburg.

The Åland Islands and Helsinki

Mägi was 27 years old and had not completed a single work of art, although his urge to become an artist was increasing. After leaving St. Petersburg, he decided to spend the summer of 1906 with his friends in the Åland Islands. Fascinated by the romantic surroundings and following Nikolai Triik’s example Mägi took up painting for the first time. There are known to have been several painting sketches in his rented room, none of which have been preserved.

There is only one extant painting from the Åland period. It has very few of those characteristics that later became representative of Konrad Mägi’s style. Mägi finally managed to work consistently, being inspired by nature, and this pattern of living in a town and painting in the countryside characterised his lifestyle from then on.

In September 1906, Mägi and his friends left Åland for Helsinki, where Mägi studied for a short period at the Ateneum drawing school. He also started giving art lessons to Anni and August Vesanto, who soon became his friends and patrons. Anni Vesanto sold Mägi’s watercolours in her tobacco shop, but the income Mägi received from it was insignificant. He mainly earned his living by rewriting Estonian folk songs, and as soon as he had put aside a sufficient sum, he decided to travel to Paris at the end of August 1907.

Paris

Mägi’s first period in Paris lasted from September 1907 to the spring of 1908. “I’ve been in Paris for two days. I did not like Germany at all. Their technology was fantastic, but their stupidity was even more fantastic. France is completely different, the French themselves are truly likeable. Paris is an interesting city. There is a lot of art here to see. Overall, I like it here, although I only had a few francs in my pocket when I arrived,” Mägi wrote two days after arriving in Paris.

In Paris, Mägi initially stayed at the sculptor Jaan Koort’s place, but later moved to the artists’ colony La Ruche. He studied drawing at the independent institutions of Académie Colarossi and Académie de la Grande Chaumière.

Mägi frequented exhibitions, but was hardly fascinated by modernist art. “Of course it does not make matters better: you can often see such rubbish there that it is pointless to talk about it,” he later wrote about Parisian art exhibitions.

It is presumed that Mägi still did not paint at that time because of a shortage of money. “All the money I had, which was not much, of course, I spent on tobacco and paper (tobacco is horribly expensive and bad), leaving nothing for material,” he wrote to August Vesanto. It is, however, possible that he did paint, but the paintings have simply gone missing.

In the winter of 1908, Nikolai Triik arrived in Paris from Norway, and at the instigation of Triik, Mägi also decided to travel through Copenhagen to Norway for the summer and to return to Paris in the autumn.

Norway

Konrad Mägi wanted to spend only a couple of months in Norway before returning to Paris. He was 30 years old and had only created a few works, whereas his heath was gradually deteriorating. In August 1908, he moved to the countryside, where he was finally able to focus on making art: he made studies to practice his craft, because his goal was to take entrance exams to the Academy of Fine Arts in Paris in autumn. Unfortunately, he did not have enough money to leave Norway, so he stayed for another two years.

In Norway, Mägi finally started to paint. He neither dated his works precisely nor provided the exact location of the motif: his goal was to set reality aside and to sense the rhythms and structures that constitute the real essence of things and phenomena. He participated in an exhibition at the Blomqvist Gallery in Oslo, but there was no breakthrough. He did, however, also send his works to Estonia to be displayed at an exhibition organised by the Noor-Eesti (Young Estonia) literary group in 1910, and that was the beginning of his rise to prominence in his home country.

Mägi’s Norwegian landscapes include both panoramic and realistic views of nature and almost hallucinatory bog landscapes.

-

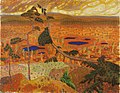

"Norwegian Landscape“, 1908-1909, oil on cardboard, Art Museum of Estonia

"Norwegian Landscape“, 1908-1909, oil on cardboard, Art Museum of Estonia

-

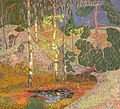

"Norwegian Landscape. (Winter Landscape)", 1908–1910, Oil on canvas, Art Museum of Estonia

"Norwegian Landscape. (Winter Landscape)", 1908–1910, Oil on canvas, Art Museum of Estonia

-

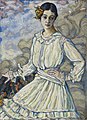

"Portrait of a Norwegian Girl", 1909, Oil on canvas, Tartu Art Museum

"Portrait of a Norwegian Girl", 1909, Oil on canvas, Tartu Art Museum

-

"Norwegian Landscape with a Pine Tree", 1908-1910, Oil on canvas, Art Museum of Estonia

"Norwegian Landscape with a Pine Tree", 1908-1910, Oil on canvas, Art Museum of Estonia

-

"Norwegian Landscape", 1909, Oil on cardboard, Art Museum of Estonia

"Norwegian Landscape", 1909, Oil on cardboard, Art Museum of Estonia

-

"Norwegian Landscape. Bog Landscape", 1908–1910, Oil on canvas, Art Museum of Estonia

"Norwegian Landscape. Bog Landscape", 1908–1910, Oil on canvas, Art Museum of Estonia

-

"Norwegian Landscape", 1909, Oil on canvas, Art Museum of Estonia

"Norwegian Landscape", 1909, Oil on canvas, Art Museum of Estonia

Back in Paris

In 1910, Konrad Mägi moved back to Paris. During his trip to Normandy in summer he began painting again, and a few works from that period have survived. In Paris, he is known to have signed at least one painting with a French spelling: K. Maegui. Three paintings by him were displayed at the 1912 exhibition of the Salon des Indépendants. Suffering from a depression, he packed his things in the spring of 1912 and came back to Estonia.

Back in Estonia

In the summer of 1913, Konrad Mägi travelled to Saaremaa. As his health was deteriorating, he was hoping that the local medicinal mud and better climate would bring him some alleviation.

Mägi mainly painted on the small island of Vilsandi, working fast and not moving about much. His brushwork is denser and more intense than in Norway, and the paintings consist of small dots of colour that create an abstract rather than a realist impression. This was the first time that Estonian landscapes were depicted using the means of modern art. The precise number of Mägi’s Saaremaa landscapes is to date unknown.

During the following years, Mägi settled down in Tartu and spent his summers painting in southern Estonia (in Kasaritsa, near Lake Pühajärve, in Otepää etc.). His works started to reveal more of his personal world outlook and experiences. In the mid-1910s, Mägi’s landscapes became comparatively dark, with walls of trees and ominous skies entering the pictorial space. This darkness can be accounted for by Mägi’s lasting depression and his progressively worsening health issues.

In the middle of the 1910s, Mägi started teaching art, and at the end of the decade, he and his peers founded the art school Pallas, whereas Mägi was elected as the first director of the school.

-

"Portrait of Alide Asmus", 1912-1913, Oil on canvas, Tartu Art Museum

"Portrait of Alide Asmus", 1912-1913, Oil on canvas, Tartu Art Museum

-

"Saaremaa Motif", 1913, Oil on canvas, Art Museum of Estonia

"Saaremaa Motif", 1913, Oil on canvas, Art Museum of Estonia

-

"Seashore in Saaremaa", 1913-1914, Oil on cardboard, Enn Kunila art collection

"Seashore in Saaremaa", 1913-1914, Oil on cardboard, Enn Kunila art collection

-

"Vilsandi Landscape", 1913-1914, Oil on canvas, Tartu Art Museum

"Vilsandi Landscape", 1913-1914, Oil on canvas, Tartu Art Museum

-

"Landscape with the Sun", 1913-1914, Oil on cardboard, Art Museum of Estonia

"Landscape with the Sun", 1913-1914, Oil on cardboard, Art Museum of Estonia

-

"Saaremaa. A Study", 1913-1914, Oil on cardboard, Enn Kunila art collection

"Saaremaa. A Study", 1913-1914, Oil on cardboard, Enn Kunila art collection

-

"Sea Kale", 1913-1914, Oil on canvas, Art Museum of Estonia

"Sea Kale", 1913-1914, Oil on canvas, Art Museum of Estonia

-

"On the Road from Viljandi to Tartu", 1915-1916, Oil on canvas, Art Museum of Estonia

"On the Road from Viljandi to Tartu", 1915-1916, Oil on canvas, Art Museum of Estonia

-

"Meditation. (Landscape with a Lady)", 1915-1916, Oil on canvas, Art Museum of Estonia

-

"Võrumaa Landscape. Lake Valgjärv", 1916-1917, Oil on canvas, Art Museum of Estonia

"Võrumaa Landscape. Lake Valgjärv", 1916-1917, Oil on canvas, Art Museum of Estonia

-

"Kasaritsa Landscape", 1916-1917, Oil on canvas, Museum of Viljandi

"Kasaritsa Landscape", 1916-1917, Oil on canvas, Museum of Viljandi

Italy

For nearly ten years, Mägi did not leave Estonia, but in September 1921, he decided to go to Italy. During that journey, urban motifs appear in his oeuvre for the first time, but not as symbols of modernity, but rather as an illusion with the main focus on buildings, stairs and other architectural objects. In the summer of 1922 Mägi travelled to Rome, where he painted surprisingly few concrete urban motifs and focussed instead on bodies of water and the sky, reducing the city to a narrow strip in the distance. He also painted on the island of Capri and in Venice.

-

"Capri Landscape", 1922–1923, Oil on canvas, Enn Kunila art collection

"Capri Landscape", 1922–1923, Oil on canvas, Enn Kunila art collection

-

"Naples Motif", 1922–1923, Oil on canvas, Art Museum of Estonia

"Naples Motif", 1922–1923, Oil on canvas, Art Museum of Estonia

-

"Park Motif with a Fountain", 1922–1923, Oil on canvas, Enn Kunila art collection

"Park Motif with a Fountain", 1922–1923, Oil on canvas, Enn Kunila art collection

-

"Italian Landscape", 1922–1923, Oil on canvas, Enn Kunila art collection

"Italian Landscape", 1922–1923, Oil on canvas, Enn Kunila art collection

Final Years

After his return to Tartu, Mägi began teaching still-life and landscape painting. Unfortunately, by the mid-1920s, he was terminally ill. During his life and in hindsight, doctors have suspected he may have suffered from gastric ulcers, gastritis, rheumatism, radiculitis and tuberculosis. In 1924, Mägi left for Germany to be treated in a sanatorium. During the two months he spent there, he was on his feet on barely three or four days. In 1925, he returned to Estonia, where he was treated in an internal disease clinic. His irritability intensified and that has in hindsight been associated with a possible diagnosis of schizophrenia, which could have been caused by untreated neurosyphilis. At the end of May, his students took him to a mental hospital, where his health deteriorated irreversibly. Konrad Mägi died on 15 August 1925 at 13:20 at the age of 46.

Portraits

Back in Estonia, Mägi stayed at his sister’s place in Tartu. In 1913, he began painting commissioned portraits, and during the following years he mainly painted upper-class ladies. He would also approach potential models himself, asking them if they would pose for him. He had a special interest in depicting characters from other ethnic groups: Jewish, Roma or Polish people, etc.

-

"Jewish Woman", 1915–1916, Oil on canvas, Art Museum of Estonia

"Jewish Woman", 1915–1916, Oil on canvas, Art Museum of Estonia

-

"Portrait of Marie Reisik", 1916, Charcoal and pastel on paper, Art Museum of Estonia

"Portrait of Marie Reisik", 1916, Charcoal and pastel on paper, Art Museum of Estonia

-

"Portrait of a Lady", 1916–1917, Oil on canvas, Art Museum of Estonia

"Portrait of a Lady", 1916–1917, Oil on canvas, Art Museum of Estonia

-

"Portrait of Alvine Käppa'', 1919, Oil on canvas, Enn Kunila art collection

"Portrait of Alvine Käppa'', 1919, Oil on canvas, Enn Kunila art collection

Perished and Found

The entire scope of Konrad Mägi’s oeuvre is still unknown, because in his lifetime Mägi never kept any regular records of his work and the estimates are only approximate, but there is proof of 290 paintings by Mägi, some of which only exist in the form of a black-and-white reproduction. It has been claimed that Mägi made a total of 400 paintings, but even that figure is only an assumption. After the artist’s death, an inventory of items found in his apartment listed 88 paintings, 60 watercolours, 16 coloured drawings and 242 drawings.

In addition to works that have gone missing or have perished, Mägi’s works have also been destroyed: one of the destroyers was the artist himself, who is said to have started wrecking his own works towards the end of his life and is reported to have told employees of the Pallas art school to clean his paintings with a solvent. Several works perished in military attacks on Tartu in July 1941. Some of Mägi’s works partly damaged in the bombing of the Tartu Art Museum and some may have been destroyed in the fire at the Art Museum of Estonia.

Today, Konrad Mägi’s paintings are scattered all around the world and there are no systematic records of the whereabouts of his work. Maie Raitar (1944-2008) was able to find and reinstate to art history dozens of Mägi’s works, but to date her thorough archive has unfortunately also gone missing. In 2018, the Konrad Mägi Foundation was created, and one of its goals was to look for missing works by Mägi. To date, approximately 40 new or previously missing works have been found, which were included in the exhibition Konrad Mägi. Unseen Paintings at the Estonian National Museum (13 October 2023 – 7 January 2024) as well as in the accompanying catalogue.

Letters

In addition to Konrad Mägi’s works, his archives also contain letters and postcards sent to his friends and peers. The majority of the existing letters by Konrad Mägi are accessible on the Konrad Mägi webpage https://konradmagi.ee/en/letters/. The original letters are kept in the Cultural Historical Archive of the Estonian Literary Museum, the archives of the Estonian Art Museum , the archives of the Tartu Art Museum , and in a private collection in Helsinki. The annotation stands for letters published in the monograph by Rudolf Paris (1932), the originals of which have gone missing. In several cases, Paris included only parts of Mägi’s letters. Only those excerpts of letters published by Paris have been included that were direct quotes; Paris’s paraphrases of Mägi’s letters have been left out. For reading feasibility, Konrad Mägi’s greetings with which he ends his letters have also been left out, unless they contain important information.

Letters to August Vesanto in Russian have been translated into Estonian by Ilona Martson. The letters were retyped by Mareli Reinhold, Liisi Tee, Kadi Kass, Aili Kuldkepp and Aili Grichin. Cf.

See also

References

- ^ Epner, Eero (2023). Konrad Mägi. Seninägemata maalid. Tallinn: Konrad Mägi Sihtasutus. p. 43.

- ^ Eero, Epner (2018). Konrad Mägi. Tallinn: Eesti Kunstimuuseum. p. 34.

- "Letter to August Vesanto from 16 December 1907".

- ^ Epner, Eero (2020). Konrad Mägi. Tallinn: Eesti Kunstimuuseum. p. 24.

- ^ Epner, Eero (2017). Konrad Mägi. Tallinn: OÜ Sperare. p. 205.

- ""A. Vaga, F. Tuglase, J. Genessi ja G. Suitsu mälestused Konrad Mäest"".

- ""Åland Motif", 1906, oil on canvas. Enn Kunila's art collection".

- Erelt, Pekka (31 March 2011). ""Ootamatu avastus Konrad Mägi elust"". Eesti Ekspress.

- ^ "Letter to Peeter Rootslane from 22 September 1907".

- "Estonian National Museum". Konrad Mägi. Retrieved 2024-12-19.

External links

- Konrad Mägi, Official homepage

- Works by Konrad Mägi at the Art Museum of Estonia