You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in German. (May 2021) Click for important translation instructions.

|

Krabat (German: [ˈkʁaːbat] ) is a character in Sorbian folklore, also dubbed the "Wendish Faust". First records of him were mentioned in 1839 minutes of the Akademischen Vereins für lausitzische Geschichte und Sprache, but all writings of the association were lost.

The character developed from an evil sorcerer into a folk hero and beneficial trickster in the course of the 19th century.

Analysis

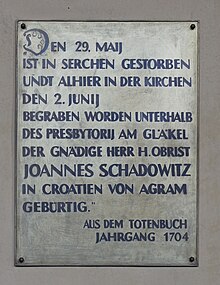

A thorough research of various historical documents established that Krabat was in fact Janko Šajatović (1624–1704), a Croat (Crabat) cavalry commander from Žumberak who came to the north of Germany in 1658 to defend the borders of Christian Europe. After he became known for his military abilities the Saxon prince invited him to be in his personal guard. As a reward, as a man of trust, the prince gave him a property in Groß Särchen, where with his knowledge and skills, since he was one of the few literate people in the area which was already inhabited by Sorbs, he helped people in various ways. He taught them to drain swamps, to build mills, he started farming in that area. A favorite among the nobility and the people, he quickly became a legend, so even after his death, stories about his heroism spread and supernatural powers were attributed to him, which resulted in sagas and legends about him that were an inspiration to many writers.

The tale of Krabat's apprenticeship to an evil sorcerer with malefic powers can be classified, in folkloristic studies, as Aarne–Thompson–Uther ATU 325, "The Sorcerer's Apprentice".

The folk tale is centered around the area of Lusatia, most notably the settlement of Čorny Chołmc (Schwarzkollm), which today is a district of the city of Hoyerswerda, where Krabat is said to have learned his sorcerous powers.

Adaptations

The Krabat story has been adapted into several novels, notably:

- Mišter Krabat (Master Krabat) (1954) by Měrćin Nowak-Njechorński [hsb]

- Čorny młyn (The Black Mill) (1968) by Jurij Brězan, on which the film Die Schwarze Mühle was based.

- Krabat (1971) by Otfried Preußler, which inspired the East German TV film Die schwarze Mühle ("The Black Mill") (1975), the Czech film Čarodějův učeň (1977) and the German film Krabat (2008). The Krabat album by German Goth band ASP is also inspired by this version of the legend.

See also

References

- Tomasović Bock, Nikolina (26 December 2016). "Krabat - tko je zapravo Hrvat kojemu se dive mali Nijemci?". dw.com (in Croatian). Retrieved 2 September 2021.

- Troshkova, A (2019). "The tale type 'The Magician and His Pupil' in East Slavic and West Slavic traditions (based on Russian and Lusatian ATU 325 fairy tales)". Indo-European Linguistics and Classical Philology. XXIII: 1022–1037. doi:10.30842/ielcp230690152376.

- "Сказание о Крабате (лужицкая сказка)" . In: "Ни далеко, ни близко, ни высоко, ни низко. Сказки славян". Leningrad: Детская литература, 1976. pp. 203-216.

- Zipes Jack, ed. (2017). The Sorcerer's Apprentice: An Anthology of Magical Tales. Illustrated by Natalie Frank. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-8563-3. pp. 323-348.

Bibliography

- Jurij Pilk, Adolf Anders, "Der wendische Faust", Sächsischer Erzähler. Illustrierte Beilage, Nr. 14 (1896), reprinted as "Die wendische Faust-Sage", Bunte Bilder aus dem Sachsenlande vol. 3 (1900), 191–201.

- Zipes Jack, ed. (2017). The Sorcerer's Apprentice: An Anthology of Magical Tales. Illustrated by Natalie Frank. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-8563-3.

- Troshkova, A (2019). "The tale type 'The Magician and His Pupil' in East Slavic and West Slavic traditions (based on Russian and Lusatian ATU 325 fairy tales)". Indo-European Linguistics and Classical Philology. XXIII: 1022–1037. doi:10.30842/ielcp230690152376.

Further reading

- Brězan, Jurij, and Gregory H. Wolf. "The Survival of a Culture: An Interview with the Sorbian Author Jurij Brězan." World Literature Today 75, no. 3/4 (2001): 42-52. doi:10.2307/40156748.

- Jurich, Marilyn. "Children Stranded "Among These Dark Satanic Mills": The Child's Response to Evil in Fantasies From Four Different Countries." Journal of the Fantastic in the Arts 13, no. 3 (51) (2003): 271-81. www.jstor.org/stable/43308613.

- Kudela, Jean. "Jurij Brĕzan (1916-2006)". In: Revue des études slaves, tome 77, fascicule 1-2, 2006. Le théâtre d'aujourd'hui en Bosnie-Herzégovine Croatie, Serbie et Monténégro, sous la direction de Sava Andjelković et Paul-Louis Thomas. pp. 309–310.

- Raede, H. "LA LITTÉRATURE LUSACIENNE AU XXe SIÈCLE." Études Slaves Et Est-Européennes / Slavic and East-European Studies 9, no. 1/2 (1964): 38-48. www.jstor.org/stable/41055929.

- Žura-Vrkić, Slavica. "Krabat - Lužičkosrpski čarobnjak hrvatskih korijena" In: Ethnologica Dalmatica br. 20 (2013): 69-80. https://hrcak.srce.hr/107478

This article relating to a European folklore is a stub. You can help Misplaced Pages by expanding it. |