| Part of the series on |

| Japanese mythology |

|---|

|

| Texts and myths |

| Sacred objects |

| Mythical locations |

Kusanagi-no-Tsurugi (草薙の剣) is a legendary Japanese sword and one of three Imperial Regalia of Japan. It was originally called Ame-no-Murakumo-no-Tsurugi (天叢雲剣, "Heavenly Sword of Gathering Clouds"), but its name was later changed to the more popular Kusanagi-no-Tsurugi ("Grass-Cutting Sword"). In folklore, the sword represents the virtue of valor.

Legends

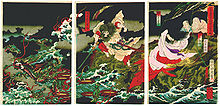

The history of the Kusanagi-no-Tsurugi extends into legend. According to Kojiki, the god Susanoo encountered a grieving family of kunitsukami ("gods of the land") headed by Ashinazuchi (足名椎) in Izumo Province. When Susanoo inquired of Ashinazuchi, he told him that his family was being terrorized by the fearsome Yamata no Orochi, an eight-headed serpent of Koshi, who had consumed seven of the family's eight daughters, and that the creature was coming for his final daughter, Kushinada-hime (奇稲田姫). Susanoo investigated the creature, and after an abortive encounter he returned with a plan to defeat it. In return, he asked for Kushinada-hime's hand in marriage, which was agreed. Transforming her temporarily into a comb (one interpreter reads this section as "using a comb he turns into Kushinada-hime") to have her company during battle, he detailed his plan into steps.

He instructed that eight vats of sake (rice wine) be prepared and put on individual platforms positioned behind a fence with eight gates. The monster took the bait and put one of its heads through each gate. With this distraction, Susanoo attacked and slew the beast (with his sword Worochi no Ara-masa), chopping off each head and then proceeded to do the same to the tails. In the fourth tail, he discovered a great sword inside the body of the serpent which he called Ame-no-Murakumo-no-Tsurugi. He presented the sword to the goddess Amaterasu to settle an old grievance. The Nihon Shoki adds more to the story. It says Susanoo had Ame-no-Fuyukinu deliver the sword. A rite at Hinomisaki Shrine honors this delivery to this day.

Generations later, during the reign of the 12th Emperor Keikō, Ame-no-Murakumo-no-Tsurugi was given to the great warrior, Yamato Takeru, as part of a pair of gifts given by his aunt, Yamatohime-no-mikoto, the Shrine Maiden of Ise Shrine, to protect her nephew in times of peril.

These gifts came in handy when Yamato Takeru was lured onto an open grassland during a hunting expedition by a treacherous warlord. The lord had fiery arrows loosed to ignite the grass and trap Yamato Takeru in the field so that he would burn to death. He also killed the warrior's horse to prevent his escape. Desperately, Yamato Takeru used the Ame-no-Murakumo-no-Tsurugi to cut back the grass and remove fuel from the fire, but in doing so, he discovered that the sword enabled him to control the wind and cause it to move in the direction of his swing. Taking advantage of this magic, Yamato Takeru used his other gift, fire strikers, to enlarge the fire in the direction of the lord and his men, and he used the winds controlled by the sword to sweep the blaze toward them. In triumph, Yamato Takeru renamed the sword Kusanagi-no-Tsurugi ("Grass-Cutting Sword") to commemorate his narrow escape and victory. Eventually, Yamato Takeru married and later fell in battle against a monster, after ignoring his wife's advice to take the sword with him.

Folklore

Although the sword is mentioned in the Kojiki, this book is a collection of Japanese myths and is not considered a historical document. The first reliable historical mention of the sword is in the Nihon Shoki. Although the Nihon Shoki also contains mythological stories that are not considered reliable history, it records some events that were contemporary or nearly contemporary to its writing, and these sections of the book are considered historical. In the Nihon Shoki, the Kusanagi was removed from the Imperial palace in 688, and moved to Atsuta Shrine after the sword was blamed for causing Emperor Tenmu to fall ill. Along with the jewel (Yasakani no Magatama) and the mirror (Yata no Kagami), it is one of the three Imperial Regalia of Japan, the sword representing the virtue of valor.

Kusanagi is allegedly kept at Atsuta Shrine but is not available for public display. During the Edo period, while performing various repairs and upkeep at Atsuta Shrine, including replacement of the outer wooden box housing the sword, the Shinto priest Matsuoka Masanao claimed to have been one of several priests to have seen the sword. Per his account, "a stone box was inside a wooden box of length 150 cm (59 in), with red clay stuffed into the gap between them. Inside the stone box was a hollowed log of a camphor tree, acting as another box, with an interior lined with gold. Above that was placed a sword. Red clay was also stuffed between the stone box and the camphor tree box. The sword was about 82 cm (32 in) long. Its blade resembled a calamus leaf. The middle of the sword had a thickness from the grip about 18 cm (7.1 in) with an appearance like a fish spine. The sword was fashioned in a white metallic color, and well maintained." After witnessing the sword, the grand priest was banished and the other priests, except for Matsuoka, died from strange diseases. The above account therefore comes from the only survivor, Matsuoka.

In The Tale of the Heike, a collection of oral stories transcribed in 1371, the sword is lost at sea after the defeat of the Heike in the Battle of Dan-no-ura, a naval battle that ended in the defeat of the Heike clan forces and the child Emperor Antoku at the hands of Minamoto no Yoshitsune. In the tale, upon hearing of the Navy's defeat, the Emperor's grandmother, Taira no Tokiko, led the Emperor and his entourage to commit suicide by drowning in the waters of the strait, taking with her two of the three Imperial Regalia: the sacred jewel and the sword Kusanagi. The sacred mirror was recovered in extremis when one of the ladies-in-waiting was about to jump with it into the sea. Although the sacred jewel is said to have been found in its casket floating on the waves, Kusanagi was lost forever. Although written about historical events, The Tale of the Heike is a collection of epic poetry passed down orally and written down nearly 200 years after the actual events, so it has questionable reliability as a historical document.

Another story holds that the sword was reportedly stolen again in the sixth century by a monk from Silla. However, his ship allegedly sank at sea, allowing the sword to wash ashore at Ise, where it was recovered by Shinto priests.

Current status

Because no one is allowed to see the sword due to its divinity and Shinto tradition, the exact shape and condition of the sword has not been confirmed. The most recent appearance of the sword was in 2019 when Emperor Naruhito ascended the throne; the sword (as well as the jewel Yasakani no Magatama, the Emperor's privy seal and the State Seal) were shrouded in packages.

Replicas of the sword were made as early as the 9th century, and the original is entrusted to Atsuta Shrine in Nagoya. According to Shinsuke Takenaka of the Institute of Moralogy, a 12th-century replica preserved in the Imperial palace is the one used in coronation ceremonies, probably due to the fragility of the original sword.

Other emperors' swords

The Kusanagi sword is always hidden because of its divinity, and it is put in a box and put up by the chamberlain at the time of the enthronement ceremony. However, the Japanese sword held up by the emperor's chamberlain, which can be seen at various imperial ceremonies, is always close to the emperor as an amulet, and is called Hi no Omashi no Gyoken (昼御座御剣, meaning 'sword of the throne in the daytime'). Hi no Omashi no Gyoken has changed over time; at present, two tachi made by swordsmiths Nagamitsu and Yukihira in the Kamakura period play the role. Apart from these swords, the Imperial Family owns many swords, which are managed by the Imperial Household Agency. For example, one of the Tenka-Goken, Onimaru is owned by the Imperial Family.

The sword of the Crown Prince of Japan

The Japanese crown prince has inherited two tachi, Tsubokiri no Gyoken or Tsubokiri no Mitsurugi (壺切御剣, meaning "sword that cut a pot"), and Yukihira Gyoken (行平御剣, meaning "sword made by Yukihira"). While the Kusanagi sword is forbidden to be seen because of its divinity and is always kept in a box, the Crown Prince's sword is worn by the Crown Prince with the traditional costume sokutai at an official ceremony of the Imperial Household.

The Tsubokiri sword is the most important sword owned by the Crown Prince, given by the Emperor as proof of the official Crown Prince after the ceremony of his inauguration. Its origin is that it was given by Emperor Uda when Emperor Daigo became Crown Prince in 893, and the present, the Tsubokiri sword is the second generation, made in the late Heian period. The Yukihira sword is a tachi made by Yukihira, a swordsmith in the Kamakura period, and the Crown Prince inherits it from the Emperor before his inauguration ceremony and wears it in various Imperial events except for the Niiname-sai festival. This Yukihira sword is different from the Emperor's Hi no Omashi no Gyoken.

See also

References

- ^ Perez, Louis G. (2013). Japan at War: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 191–192. ISBN 978-1-59884-741-3.

- ^ Roberts, Jeremy (2009). Japanese Mythology A to Z. Infobase Publishing. p. 110. ISBN 978-1-4381-2802-3.

- Nihongi: Chronicles of Japan from the Earliest Times to A.D. 697. Translated by Aston, William George. Tuttle Publishing. 2005. Book I, part 1, page 56. ISBN 9780804836746.

- ^ "Amenofuyukinu, Amenofukine | 國學院大學デジタルミュージアム". 2023-11-14. Archived from the original on 2023-11-14. Retrieved 2023-11-14.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - Nihongi: Chronicles of Japan from the Earliest Times to A.D. 697. Translated by Aston, William George. Tuttle Publishing. 2005. Book I, part 1, page 53. ISBN 9780804836746.

- Roberts, Jeremy (2009). Japanese Mythology A to Z. Infobase Publishing. p. 115. ISBN 978-1-4381-2802-3.

- First appears in Endorsement of Gyokusensyu (玉籤集裏書, Gyokusenshū uragaki) from around 1725, written by Tamaki Masahide, a Shinto priest of Umenomiya Shrine. This text is then mentioned in the Investigation of Imperial Regalia (神器考證, Jingi Kōshō), published 1898, written by Kurita Hiroshi. Kokugakuin. http://kindai.ndl.go.jp/info:ndljp/pid/815487

- The Tales of the Heike. Translated by Watson, Burton. Columbia University Press. 2006. p. 142. ISBN 9780231138024.

- ^ The Tale of the Heike. Translated by McCullough, Helen Craig. Stanford University Press. 1988. ISBN 9780804714181.

- "Kurayoshi Plain". Encyclopedia of Japan. Tokyo: Shogakukan. 2012. Retrieved 2012-04-12.

- Anna Jones (27 April 2019). "Akihito and Japan's Imperial Treasures that make a man an emperor". BBC. Archived from the original on March 24, 2022.

- ^ 儀式で天皇陛下のお側に登場する太刀はもちろん神器ではなく、平安以来の天皇の守り刀「昼御座御剣(ひのおましのごけん)」. Tadamoto Hachijō. November 8, 2019

- ^ "秋篠宮さまに授けられる皇太子の守り刀 ベールに包まれた「壺切御剣」とは?". Mainichi Shimbun. November 7, 2020. Archived from the original on 2020-11-07. Retrieved November 7, 2020.

- Naumann, Nelly (1992). "The kusanagi sword" (PDF). In Nenrin-Jahresringe: Festgabe für Hans A. Dettmer. Ed. Klaus Müller. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 1992. –170.

| Japanese mythology | ||

|---|---|---|

| Mythic texts |   | |

| Japanese creation myth | ||

| Takamagahara mythology | ||

| Izumo mythology | ||

| Hyūga mythology | ||

| Human age | ||

| Mythological locations | ||

| Mythological weapons | ||

| Major Buddhist figures | ||

| Seven Lucky Gods | ||

| Legendary creatures | ||

| Other | ||

| Notable swords | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Historical |

|  | ||||

| Mythical or legendary |

| |||||

| Note: some of the existing swords are named after earlier legendary ones. | ||||||

| Shinto shrines | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||