United States labor law sets the rights and duties for employees, labor unions, and employers in the US. Labor law's basic aim is to remedy the "inequality of bargaining power" between employees and employers, especially employers "organized in the corporate or other forms of ownership association". Over the 20th century, federal law created minimum social and economic rights, and encouraged state laws to go beyond the minimum to favor employees. The Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 requires a federal minimum wage, currently $7.25 but higher in 29 states and D.C., and discourages working weeks over 40 hours through time-and-a-half overtime pay. There are no federal laws, and few state laws, requiring paid holidays or paid family leave. The Family and Medical Leave Act of 1993 creates a limited right to 12 weeks of unpaid leave in larger employers. There is no automatic right to an occupational pension beyond federally guaranteed Social Security, but the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974 requires standards of prudent management and good governance if employers agree to provide pensions, health plans or other benefits. The Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970 requires employees have a safe system of work.

A contract of employment can always create better terms than statutory minimum rights. But to increase their bargaining power to get better terms, employees organize labor unions for collective bargaining. The Clayton Act of 1914 guarantees all people the right to organize, and the National Labor Relations Act of 1935 creates rights for most employees to organize without detriment through unfair labor practices. Under the Labor Management Reporting and Disclosure Act of 1959, labor union governance follows democratic principles. If a majority of employees in a workplace support a union, employing entities have a duty to bargain in good faith. Unions can take collective action to defend their interests, including withdrawing their labor on strike. There are not yet general rights to directly participate in enterprise governance, but many employees and unions have experimented with securing influence through pension funds, and representation on corporate boards.

Since the Civil Rights Act of 1964, all employing entities and labor unions have a duty to treat employees equally, without discrimination based on "race, color, religion, sex, or national origin". There are separate rules for sex discrimination in pay under the Equal Pay Act of 1963. Additional groups with "protected status" were added by the Age Discrimination in Employment Act of 1967 and the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990. There is no federal law banning all sexual orientation or identity discrimination, but 22 states had passed laws by 2016. These equality laws generally prevent discrimination in hiring and terms of employment, and make discharge because of a protected characteristic unlawful. In 2020, the Supreme Court of the United States ruled in Bostock v. Clayton County that discrimination solely on the grounds of sexual orientation or gender identity violates Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. There is no federal law against unjust discharge, and most states also have no law with full protection against wrongful termination of employment. Collective agreements made by labor unions and some individual contracts require that people are only discharged for a "just cause". The Worker Adjustment and Retraining Notification Act of 1988 requires employing entities give 60 days notice if more than 50 or one third of the workforce may lose their jobs. Federal law has aimed to reach full employment through monetary policy and spending on infrastructure. Trade policy has attempted to put labor rights in international agreements, to ensure open markets in a global economy do not undermine fair and full employment.

History

Main articles: History of labor law in the United States and Labor history of the United States

Modern US labor law mostly comes from statutes passed between 1935 and 1974, and changing interpretations of the US Supreme Court. However, laws regulated the rights of people at work and employers from colonial times on. Before the Declaration of Independence in 1776, the common law was either uncertain or hostile to labor rights. Unions were classed as conspiracies, and potentially criminal. It tolerated slavery and indentured servitude. From the Pequot War in Connecticut from 1636 onwards, Native Americans were enslaved by European settlers. More than half of the European immigrants arrived as prisoners, or in indentured servitude, where they were not free to leave their employers until a debt bond had been repaid. Until its abolition, the Atlantic slave trade brought millions of Africans to do forced labor in the Americas.

However, in 1772, the English Court of King's Bench held in Somerset v Stewart that slavery was to be presumed unlawful at common law. Charles Stewart from Boston, Massachusetts had bought James Somerset as a slave and taken him to England. With the help of abolitionists, Somerset escaped and sued for a writ of habeas corpus (that "holding his body" had been unlawful). Lord Mansfield, after declaring he should "let justice be done whatever be the consequence", held that slavery was "so odious" that nobody could take "a slave by force to be sold" for any "reason whatever". This was a major grievance of southern slave owning states, leading up to the American Revolution in 1776. The 1790 United States census recorded 694,280 slaves (17.8 per cent) of a total 3,893,635 population. After independence, the British Empire halted the Atlantic slave trade in 1807, and abolished slavery in its own territories, by paying off slave owners in 1833. In the US, northern states progressively abolished slavery. However, southern states did not. In Dred Scott v. Sandford the Supreme Court held the federal government could not regulate slavery, and also that people who were slaves had no legal rights in court. The American Civil War was the result. President Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation in 1863 made abolition of slavery a war aim, and the Thirteenth Amendment of 1865 enshrined the abolition of most forms of slavery in the Constitution. Former slave owners were further prevented from holding people in involuntary servitude for debt by the Peonage Act of 1867. In 1868, the Fourteenth Amendment ensured equal access to justice, and the Fifteenth Amendment required that everyone would have the right to vote. The Civil Rights Act of 1875 was also meant to ensure equality in access to housing and transport, but in the Civil Rights Cases, the Supreme Court found it was "unconstitutional", ensuring that racial segregation would continue. In dissent, Harlan J said the majority was leaving people "practically at the mercy of corporations". Even if people were formally free, they remained factually dependent on property owners for work, income and basic services.

—Abraham Lincoln, First Annual Message (1861)Labor is prior to and independent of capital. Capital is only the fruit of labor, and could never have existed if labor had not first existed. Labor is the superior of capital, and deserves much the higher consideration ... The prudent, penniless beginner in the world labors for wages awhile, saves a surplus with which to buy tools or land for himself, then labors on his own account another while, and at length hires another new beginner to help him. This is the just and generous and prosperous system which opens the way to all, gives hope to all, and consequent energy and progress and improvement of condition to all. No men living are more worthy to be trusted than those who toil up from poverty; none less inclined to take or touch aught which they have not honestly earned. Let them beware of surrendering a political power which they already possess, and which if surrendered will surely be used to close the door of advancement against such as they and to fix new disabilities and burdens upon them till all of liberty shall be lost.

Like slavery, common law repression of labor unions was slow to be undone. In 1806, Commonwealth v. Pullis held that a Philadelphia shoemakers union striking for higher wages was an illegal "conspiracy", even though corporations—combinations of employers—were lawful. Unions still formed and acted. The first federation of unions, the National Trades Union was established in 1834 to achieve a 10 hour working day, but it did not survive the soaring unemployment from the financial Panic of 1837. In 1842, Commonwealth v. Hunt, held that Pullis was wrong, after the Boston Journeymen Bootmakers' Society struck for higher wages. The first instance judge said unions would "render property insecure, and make it the spoil of the multitude, would annihilate property, and involve society in a common ruin". But in the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court, Shaw CJ held people "are free to work for whom they please, or not to work, if they so prefer" and could "agree together to exercise their own acknowledged rights, in such a manner as best to subserve their own interests." This stopped criminal cases, although civil cases persisted. In 1869 an organisation called the Knights of Labor was founded by Philadelphia artisans, joined by miners 1874, and urban tradesmen from 1879. It aimed for racial and gender equality, political education and cooperative enterprise, yet it supported the Alien Contract Labor Law of 1885 which suppressed workers migrating to the US under a contract of employment.

Industrial conflicts on railroads and telegraphs from 1883 led to the foundation of the American Federation of Labor in 1886, with the simple aim of improving workers wages, housing and job security "here and now". It also aimed to be the sole federation, to create a strong, unified labor movement. Business reacted with litigation. The Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890, which was intended to sanction business cartels acting in restraint of trade, was applied to labor unions. In 1895, the US Supreme Court in In re Debs affirmed an injunction, based on the Sherman Act, against the striking workers of the Pullman Company. The strike leader Eugene Debs was put in prison. In notable dissent among the judiciary, Holmes J argued in Vegelahn v. Guntner that any union taking collective action in good faith was lawful: even if strikes caused economic loss, this was equally legitimate as economic loss from corporations competing with one another. Holmes J was elevated to the US Supreme Court, but was again in a minority on labor rights. In 1905, Lochner v. New York held that New York limiting bakers' working day to 60 hours a week violated employers' freedom of contract. The Supreme Court majority supposedly unearthed this "right" in the Fourteenth Amendment, that no State should "deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law." With Harlan J, Holmes J dissented, arguing that the "constitution is not intended to embody a particular economic theory" but is "made for people of fundamentally differing views". On questions of social and economic policy, courts should never declare legislation "unconstitutional". The Supreme Court, however, accelerated its attack on labor in Loewe v. Lawlor, holding that triple damages were payable by a striking union to its employers under the Sherman Act of 1890. This line of cases was finally quashed by the Clayton Act of 1914 §6. This removed labor from antitrust law, affirming that the "labor of a human being is not a commodity or article of commerce" and nothing "in the antitrust laws" would forbid the operation of labor organizations "for the purposes of mutual help".

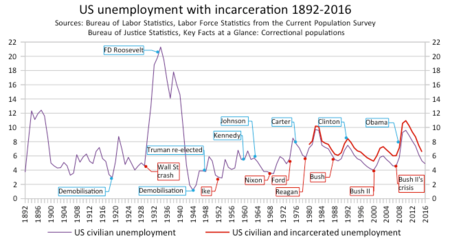

Throughout the early 20th century, states enacted labor rights to advance social and economic progress. But despite the Clayton Act, and abuses of employers documented by the Commission on Industrial Relations from 1915, the Supreme Court struck labor rights down as unconstitutional, leaving management powers virtually unaccountable. In this Lochner era, the Courts held that employers could force workers to not belong to labor unions, that a minimum wage for women and children was void, that states could not ban employment agencies charging fees for work, that workers could not strike in solidarity with colleagues of other firms, and even that the federal government could not ban child labor. It also imprisoned socialist activists, who opposed the fighting in World War I, meaning that Eugene Debs ran as the Socialist Party's candidate for president in 1920 from prison. Critically, the courts held state and federal attempts to create Social Security to be unconstitutional. Because they were unable to save in safe public pensions, millions of people bought shares in corporations, causing massive growth in the stock market. Because the Supreme Court precluded regulation for good information on what people were buying, corporate promoters tricked people into paying more than stocks were really worth. The Wall Street Crash of 1929 wiped out millions of people's savings. Business lost investment and fired millions of workers. Unemployed people had less to spend with businesses. Business fired more people. There was a downward spiral into the Great Depression.

This led to the election of Franklin D. Roosevelt for president in 1932, who promised a "New Deal". Government committed to create full employment and a system of social and economic rights enshrined in federal law. But despite the Democratic Party's overwhelming electoral victory, the Supreme Court continued to strike down legislation, particularly the National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933, which regulated enterprise in an attempt to ensure fair wages and prevent unfair competition. Finally, after Roosevelt's second overwhelming victory in 1936, and Roosevelt's threat to create more judicial positions if his laws were not upheld, one Supreme Court judge switched positions. In West Coast Hotel Co. v. Parrish the Supreme Court found that minimum wage legislation was constitutional, letting the New Deal go on. In labor law, the National Labor Relations Act of 1935 guaranteed every employee the right to unionize, collectively bargain for fair wages, and take collective action, including in solidarity with employees of other firms. The Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 created the right to a minimum wage, and time-and-a-half overtime pay if employers asked people to work over 40 hours a week. The Social Security Act of 1935 gave everyone the right to a basic pension and to receive insurance if they were unemployed, while the Securities Act of 1933 and the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 ensured buyers of securities on the stock market had good information. The Davis–Bacon Act of 1931 and Walsh–Healey Public Contracts Act of 1936 required that in federal government contracts, all employers would pay their workers fair wages, beyond the minimum, at prevailing local rates. To reach full employment and out of depression, the Emergency Relief Appropriation Act of 1935 enabled the federal government to spend huge sums of money on building and creating jobs. This accelerated as World War II began. In 1944, his health waning, Roosevelt urged Congress to work towards a "Second Bill of Rights" through legislative action, because "unless there is security here at home there cannot be lasting peace in the world" and "we shall have yielded to the spirit of Fascism here at home."

Although the New Deal had created a minimum safety net of labor rights, and aimed to enable fair pay through collective bargaining, a Republican dominated Congress revolted when Roosevelt died. Against the veto of President Truman, the Taft–Hartley Act of 1947 limited the right of labor unions to take solidarity action, and enabled states to ban unions requiring all people in a workplace becoming union members. A series of Supreme Court decisions, held the National Labor Relations Act of 1935 not only created minimum standards, but stopped or "preempted" states enabling better union rights, even though there was no such provision in the statute. Labor unions became extensively regulated by the Labor Management Reporting and Disclosure Act of 1959. Post-war prosperity had raised people's living standards, but most workers who had no union, or job security rights remained vulnerable to unemployment. As well as the crisis triggered by Brown v. Board of Education, and the need to dismantle segregation, job losses in agriculture, particularly among African Americans was a major reason for the civil rights movement, culminating in the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom led by Martin Luther King Jr. Although Roosevelt's Executive Order 8802 of 1941 had prohibited racial discrimination in the national defense industry, people still suffered discrimination because of their skin color across other workplaces. Also, despite the increasing numbers of women in work, sex discrimination was endemic. The government of John F. Kennedy introduced the Equal Pay Act of 1963, requiring equal pay for women and men. Lyndon B. Johnson introduced the Civil Rights Act of 1964, finally prohibiting discrimination against people for "race, color, religion, sex, or national origin." Slowly, a new generation of equal rights laws spread. At federal level, this included the Age Discrimination in Employment Act of 1967, the Pregnancy Discrimination Act of 1978, and the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990, now overseen by the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission.

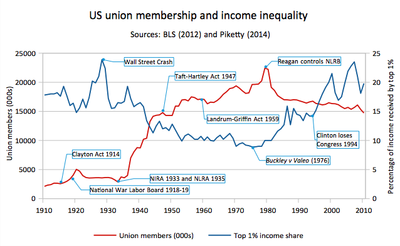

Although people, in limited fields, could claim to be equally treated, the mechanisms for fair pay and treatment were dismantled after the 1970s. The last major labor law statute, the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974 created rights to well regulated occupational pensions, although only where an employer had already promised to provide one: this usually depended on collective bargaining by unions. But in 1976, the Supreme Court in Buckley v. Valeo held anyone could spend unlimited amounts of money on political campaigns, as a part of the First Amendment right to "freedom of speech". After the Republican President Reagan took office in 1981, he dismissed all air traffic control staff who went on strike, and replaced the National Labor Relations Board members with pro-management men. Dominated by Republican appointees, the Supreme Court suppressed labor rights, removing rights of professors, religious school teachers, or illegal immigrants to organize in a union, allowing employees to be searched at work, and eliminating employee rights to sue for medical malpractice in their own health care. Only limited statutory changes were made. The Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986 criminalized large numbers of migrants. The Worker Adjustment and Retraining Notification Act of 1988 guaranteed workers some notice before a mass termination of their jobs. The Family and Medical Leave Act of 1993 guaranteed a right to 12 weeks leave to take care for children after birth, all unpaid. The Small Business Job Protection Act of 1996 cut the minimum wage, by enabling employers to take the tips of their staff to subsidize the minimum wage. A series of proposals by Democratic and independent politicians to advance labor rights were not enacted, and the United States began to fall behind most other developed countries in labor rights.

In relation to federal government contracting, Executive Order 13673, entitled Fair Pay and Safe Workplaces, was issued by President Barack Obama on 31 July 2014. It contained "new requirements designed to increase efficiency and cost savings in the Federal contracting process", specifically referring to "contracting with responsible sources who comply with labor laws". The Occupational Safety and Health Administration published guidance on 25 August 2016. The order listed 14 federal laws which were defined as "labor laws", and extended coverage to "equivalent state laws". A breach of any of these laws during the three year period preceding the contract award was treated as non-compliance; for a contract valued over $500,000, contracting officers were to consider such violations, and any corrective actions taken by the business concerned, in determining contract award. Similar provisions were built into sub-contracting arrangements. To support compliance, each federal agency was required to appoint a "Labor Compliance Advisor". The order was revoked by President Donald Trump on 27 March 2017 under Executive Order 13782.

Contract and rights at work

See also: UK labour law, Canadian labour law, Australian labour law, European labour law, German labour law, French labour law, Indian labour law, and South African labour law

Contracts between employees and employers (mostly corporations) usually begin an employment relationship, but are often not enough for a decent livelihood. Because individuals lack bargaining power, especially against wealthy corporations, labor law creates legal rights that override arbitrary market outcomes. Historically, the law faithfully enforced property rights and freedom of contract on any terms, whether or not this was inefficient, exploitative and unjust. In the early 20th century, as more people favored the introduction of democratically determined economic and social rights over rights of property and contract, state and federal governments introduced law reform. First, the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 created a minimum wage (now $7.25 at federal level, higher in 28 states) and overtime pay of one and a half times. Second, the Family and Medical Leave Act of 1993 creates very limited rights to take unpaid leave. In practice, good employment contracts improve on these minimums. Third, while there is no right to an occupational pension or other benefits, the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974 ensures employers guarantee those benefits if they are promised. Fourth, the Occupational Safety and Health Act 1970 demands a safe system of work, backed by professional inspectors. Individual states are often empowered to go beyond the federal minimum, and function as laboratories of democracy in social and economic rights, where they have not been constrained by the US Supreme Court.

Scope of protection

| Workplace protection cases | |

|---|---|

| United States v. Silk, 331 U.S. 704 (1947) | |

| NLRB v. Hearst Publications, 322 U.S. 111 (1944) | |

| Golden State Bottling Co Inc v. NLRB, 414 U.S. 168 (1973) | |

| South Prairie Co v. Local No 627 IUOE, 425 U.S. 800 (1976) | |

| NLRB v. Yeshiva University, 444 U.S. 672 (1980) | |

| Lemmerman v. A.T. Williams Oil Co., 350 SE 2d 83 (1986) | |

| Community for Creative Non-Violence v. Reid, 490 U.S. 730 (1989) | |

| Nationwide Mut. Ins. Co. v. Darden, 503 U.S. 318 (1992) | |

| Castillo v. Case Farms of Ohio, 96 F Supp. 2d 578 (1999) | |

| Clackamas Gastroenterology Ass v. Wells, 538 U.S. 440 (2003) | |

| Christopher v. SmithKline Beecham Corp, 567 U.S. 142 (2012) | |

| See U.S. labor law and inequality of bargaining power |

Common law, state and federal statutes usually confer labor rights on "employees", but not people who are autonomous and have sufficient bargaining power to be "independent contractors". In 1994, the Dunlop Commission on the Future of Worker-Management Relations: Final Report recommended a unified definition of an employee under all federal labor laws, to reduce litigation, but this was not implemented. As it stands, Supreme Court cases have stated various general principles, which will apply according to the context and purpose of the statute in question. In NLRB v. Hearst Publications, Inc., newsboys who sold newspapers in Los Angeles claimed that they were "employees", so that they had a right to collectively bargain under the National Labor Relations Act of 1935. The newspaper corporations argued the newsboys were "independent contractors", and they were under no duty to bargain in good faith. The Supreme Court held the newsboys were employees, and common law tests of employment, particularly the summary in the Restatement of the Law of Agency, Second §220, were no longer appropriate. They were not "independent contractors" because of the degree of control employers had. But the National Labor Relations Board could decide itself who was covered if it had "a reasonable basis in law." Congress reacted, first, by explicitly amending the NLRA §2(1) so that independent contractors were exempt from the law while, second, disapproving that the common law was irrelevant. At the same time, the Supreme Court decided United States v. Silk, holding that "economic reality" must be taken into account when deciding who is an employee under the Social Security Act of 1935. This meant a group of coal loaders were employees, having regard to their economic position, including their lack of bargaining power, the degree of discretion and control, and the risk they assumed compared to the coal businesses they worked for. By contrast, the Supreme Court found truckers who owned their own trucks, and provided services to a carrier company, were independent contractors. Thus, it is now accepted that multiple factors of traditional common law tests may not be replaced if a statute gives no further definition of "employee" (as is usual, e.g., the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938, Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974, Family and Medical Leave Act of 1993). Alongside the purpose of labor legislation to mitigate inequality of bargaining power and redress the economic reality of a worker's position, the multiple factors found in the Restatement of Agency must be considered, though none is necessarily decisive.

Common law agency tests of who is an "employee" take account of an employer's control, if the employee is in a distinct business, degree of direction, skill, who supplies tools, length of employment, method of payment, the regular business of the employer, what the parties believe, and whether the employer has a business. Some statutes also make specific exclusions that reflect the common law, such as for independent contractors, and others make additional exceptions. In particular, the National Labor Relations Act of 1935 §2(11) exempts supervisors with "authority, in the interest of the employer", to exercise discretion over other employees' jobs and terms. This was originally a narrow exception. Controversially, in NLRB v. Yeshiva University, a 5 to 4 majority of the Supreme Court held that full time professors in a university were excluded from collective bargaining rights, on the theory that they exercised "managerial" discretion in academic matters. The dissenting judges pointed out that management was actually in the hands of university administration, not professors. In NLRB v. Kentucky River Community Care, Inc., the Supreme Court held, again 5 to 4, that six registered nurses who exercised supervisory status over others fell into the "professional" exemption. Stevens J, for the dissent, argued that if "the 'supervisor' is construed too broadly", without regard to the Act's purpose, protection "is effectively nullified". Similarly, under the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938, in Christopher v. SmithKline Beecham Corp., the Supreme Court held 5 to 4 that a traveling medical salesman for GSK of four years was an "outside salesman", and so could not claim overtime. People working unlawfully are often regarded as covered, so as not to encourage employers to exploit vulnerable employees. For instance in Lemmerman v. A.T. Williams Oil Co., under the North Carolina Workers' Compensation Act an eight-year-old boy was protected as an employee, even though children working under the age of 8 was unlawful. However, in Hoffman Plastic Compounds, Inc. v. NLRB, the Supreme Court held 5 to 4 that an undocumented worker could not claim back pay, after being discharged for organizing in a union. The gradual withdrawal of more and more people from the scope of labor law, by a slim majority of the Supreme Court since 1976, means that the US falls below international law standards, and standards in other democratic countries, on core labor rights, including freedom of association.

Common law tests were often important for determining who was, not just an employee, but the relevant employers who had "vicarious liability". Potentially there can be multiple, joint-employers could who share responsibility, although responsibility in tort law can exist regardless of an employment relationship. In Ruiz v. Shell Oil Co, the Fifth Circuit held that it was relevant which employer had more control, whose work was being performed, whether there were agreements in place, who provided tools, had a right to discharge the employee, or had the obligation to pay. In Local 217, Hotel & Restaurant Employees Union v. MHM Inc the question arose under the Worker Adjustment and Retraining Notification Act of 1988 whether a subsidiary or parent corporation was responsible to notify employees that the hotel would close. The Second Circuit held the subsidiary was the employer, although the trial court had found the parent responsible while noting the subsidiary would be the employer under the NLRA. Under the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938, 29 USC §203(r), any "enterprise" that is under common control will count as the employing entity. Other statutes do not explicitly adopt this approach, although the NLRB has found an enterprise to be an employer if it has "substantially identical management, business purpose, operation, equipment, customers and supervision." In South Prairie Const. Co. v. Local No. 627, International Union of Operating Engineers, AFL-CIO, the Supreme Court found that the DC Circuit had legitimately identified two corporations as a single employer given that they had a "very substantial qualitative degree of centralized control of labor", but that further determination of the relevant bargaining unit should have been remitted to the NLRB. When employees are hired through an agency, it is likely that the end-employer will be considered responsible for statutory rights in most cases, although the agency may be regarded as a joint employer.

Contracts of employment

| Employment contract cases | |

|---|---|

| JI Case Co v National Labor Relations Board, 321 US 322 (1944) | |

| Torosyan v Boehringer Ingelheim Pharma, Inc, 662 A2d 89 (1995) | |

| Demasse v ITT Corp, 984 P2d 1138 (1999) | |

| Asmus v Pacific Bell, 999 P2d 71 (2000) | |

| Stark v Circle K Corp, 751 P2d 162 (1988) | |

| Foley v Interactive Data Corp, 765 P2d 373 (1988) | |

| Alexander v Gardner-Denver Co, 415 US 36 (1974) | |

| 14 Penn Plaza LLC v Pyett, 556 US 247 (2009) | |

| See US labor law and inequality of bargaining power |

When people start work, there will almost always be a contract of employment that governs the relationship of employee and the employing entity (usually a corporation, but occasionally a human being). A "contract" is an agreement enforceable in law. Very often it can be written down, or signed, but an oral agreement is also a fully enforceable contract. Because employees have unequal bargaining power compared to almost all employing entities, most employment contracts are "standard form". Most terms and conditions are photocopied or reproduced for many people. Genuine negotiation is rare, unlike in commercial transactions between two business corporations. This has been the main justification for enactment of rights in federal and state law. The federal right to collective bargaining, by a labor union elected by its employees, is meant to reduce the inherently unequal bargaining power of individuals against organizations to make collective agreements. The federal right to a minimum wage, and increased overtime pay for working over 40 hours a week, was designed to ensure a "minimum standard of living necessary for health, efficiency, and general well-being of workers", even when a person could not get a high enough wage by individual bargaining. These and other rights, including family leave, rights against discrimination, or basic job security standards, were designed by the United States Congress and state legislatures to replace individual contract provisions. Statutory rights override even an express written term of a contract, usually unless the contract is more beneficial to an employee. Some federal statutes also envisage that state law rights can improve upon minimum rights. For example, the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 entitles states and municipalities to set minimum wages beyond the federal minimum. By contrast, other statutes such as the National Labor Relations Act of 1935, the Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970, and the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974, have been interpreted in a series of contentious judgments by the US Supreme Court to "preempt" state law enactments. These interpretations have had the effect to "stay experimentation in things social and economic" and stop states wanting to "serve as a laboratory" by improving labor rights. Where minimum rights do not exist in federal or state statutes, principles of contract law, and potentially torts, will apply.

Aside from terms in oral or written agreements, terms can be incorporated by reference. Two main sources are collective agreements and company handbooks. In JI Case Co v. National Labor Relations Board an employing corporation argued it should not have to bargain in good faith with a labor union, and did not commit an unfair labor practice by refusing, because it had recently signed individual contracts with its employees. The US Supreme Court held unanimously that the "very purpose" of collective bargaining and the National Labor Relations Act 1935 was "to supersede the terms of separate agreements of employees with terms which reflect the strength and bargaining power and serve the welfare of the group". Terms of collective agreements, to the advantage of individual employees, therefore supersede individual contracts. Similarly, if a written contract states that employees do not have rights, but an employee has been told they do by a supervisor, or rights are assured in a company handbook, they will usually have a claim. For example, in Torosyan v. Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc. the Supreme Court of Connecticut held that a promise in a handbook that an employee could be dismissed only for a good reason (or "just cause") was binding on the employing corporation. Furthermore, an employer had no right to unilaterally change the terms. Most other state courts have reached the same conclusion, that contracts cannot be altered, except for employees' benefit, without new consideration and true agreement. By contrast, a slight majority on the California Supreme Court, appointed by Republican governors, held in Asmus v. Pacific Bell that a company policy of indefinite duration can be altered after a reasonable time with reasonable notice, if it affects no vested benefits. The four dissenting judges, appointed by Democratic governors, held this was a "patently unfair, indeed unconscionable, result—permitting an employer that made a promise of continuing job security ... to repudiate that promise with impunity several years later". In addition, a basic term of good faith which cannot be waived, is implied by common law or equity in all states. This usually demands, as a general principle that "neither party shall do anything, which will have the effect of destroying or injuring the right of the other party, to receive the fruits of the contract". The term of good faith persists throughout the employment relationship. It has not yet been used extensively by state courts, compared to other jurisdictions. The Montana Supreme Court has recognized that extensive and even punitive damages could be available for breach of an employee's reasonable expectations. However others, such as the California Supreme Court limit any recovery of damages to contract breaches, but not damages regarding the manner of termination. By contrast, in the United Kingdom the requirement for "good faith" has been found to limit the power of discharge except for fair reasons (but not to conflict with statute), in Canada it may limit unjust discharge also for self-employed persons, and in Germany it can preclude the payment of wages significantly below average.

Finally, it was traditionally thought that arbitration clauses could not displace any employment rights, and therefore limit access to justice in public courts. However, in 14 Penn Plaza LLC v. Pyett, in a 5 to 4 decision under the Federal Arbitration Act of 1925, individual employment contract arbitration clauses are to be enforced according to their terms. The four dissenting judges argued that this would eliminate rights in a way that the law never intended.

Wages and pay

| Wage regulation sources | |

|---|---|

| West Coast Hotel Co v Parrish, 300 US 379 (1937) | |

| Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938, 29 USC §§201-211 | |

| ILO Minimum Wage Fixing Convention 1970 (no 131) | |

| Walling v Jacksonville Paper Co, 317 US 564 (1943) | |

| Auer v Robbins, | |

| Long Island Care at Home Ltd v Coke, | |

| Jewell Ridge Coal Corp v UMW, | |

| Anderson v Mount Clemens Pottery Co, | |

| Armour & Co v Wantock, 323 US 126 (1944) | |

| Steiner v Mitchell, 350 US 247 (1956) | |

| FLSA 1938, 29 USC §§203-207 | |

| Walling v Helmerich and Payne Inc, 323 US 37 (1944) | |

| Christensen v Harris County, | |

| Portal to Portal Act of 1947, 29 USC §§251-262 | |

| Consumer Credit Protection Act of 1968, 15 USC §§1671-1675 | |

| Skidmore v Swift & Co, | |

| See US labor law and Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 |

While contracts often determine wages and terms of employment, the law refuses to enforce contracts that do not observe basic standards of fairness for employees. Today, the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 aims to create a national minimum wage, and a voice at work, especially through collective bargaining should achieve fair wages. A growing body of law also regulates executive pay, although a system of "maximum wage" regulation, for instance by the former Stabilization Act of 1942, is not currently in force. Historically, the law actually suppressed wages, not of the highly paid, by ordinary workers. For example, in 1641 the Massachusetts Bay Colony legislature (dominated by property owners and the official church) required wage reductions, and said rising wages "tende to the ruin of the Churches and the Commonwealth". In the early 20th century, democratic opinion demanded everyone had a minimum wage, and could bargain for fair wages beyond the minimum. But when states tried to introduce new laws, the US Supreme Court held them unconstitutional. A right to freedom of contract, argued a majority, could be construed from the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendment's protection against being deprived "of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law". Dissenting judges argued that "due process" did not affect the legislative power to create social or economic rights, because employees "are not upon a full level of equality of choice with their employer".

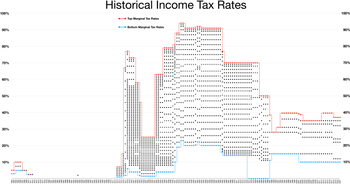

After the Wall Street Crash, and the New Deal with the election of Franklin D. Roosevelt, the majority in the US Supreme Court was changed. In West Coast Hotel Co. v. Parrish Hughes CJ held (over four dissenters still arguing for Freedom of Contract) that a Washington law setting minimum wages for women was constitutional because the state legislatures should be enabled to adopt legislation in the public interest. This ended the "Lochner era", and Congress enacted the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938. Under §202(a) the federal minimum wage aims to ensure a "standard of living necessary for health, efficiency and general well being". Under §207(a)(1), most employees (but with many exceptions) working over 40 hours a week must receive 50 per cent more overtime pay on their hourly wage. Nobody may pay lower than the minimum wage, but under §218(a) states and municipal governments may enact higher wages. This is frequently done to reflect local productivity and requirements for decent living in each region. However the federal minimum wage has no automatic mechanism to update with inflation. Because the Republican Party has opposed raising wages, the federal real minimum wage is over 33 per cent lower today than in 1968, among the lowest in the industrialized world.

Although there is a federal minimum wage, it has been restricted in (1) the scope of who it covers, (2) the time that counts to calculate the hourly minimum wage, and (3) the amount that employers' can take from their employees' tips or deduct for expenses. First, five US Supreme Court judges held in Alden v. Maine that the federal minimum wage cannot be enforced for employees of state governments, unless the state has consented, because that would violate the Eleventh Amendment. Souter J, joined by three dissenting justices, held that no such "sovereign immunity" existed in the Eleventh Amendment. Twenty-eight states, however, did have minimum wage laws higher than the federal level in 2016. Further, because the US Constitution, article one, section 8, clause 3 only allows the federal government to "regulate Commerce ... among the several States", employees of any "enterprise" under $500,000 making goods or services that do not enter commerce are not covered: they must rely on state minimum wage laws. FLSA 1938 §203(s) explicitly exempts establishments whose only employees are close family members. Under §213 the minimum wage may not be paid to 18 categories of employee, and paying overtime to 30 categories of employee. This include under §213(a)(1) employees of "bona fide executive, administrative, or professional capacity". In Auer v. Robbins police sergeants and lieutenants at the St Louis Police Department, Missouri claimed they should not be classed as executives or professional employees, and should get overtime pay. Scalia J held that, following Department of Labor guidance, the St Louis police commissioners were entitled to exempt them. This has encouraged employers to attempt to define staff as more "senior" and make them work longer hours while avoiding overtime pay. Another exemption in §213(a)(15) is for people "employed in domestic service employment to provide companionship services". In Long Island Care at Home, Ltd. v. Coke, a corporation claimed exemption, although Breyer J for a unanimous court agreed with the Department of Labor that it was only intended for carers in private homes.

Second, because §206(a)(1)(C) says the minimum wage is $7.25 per hour, courts have grappled with which hours count as "working". Early cases established that time traveling to work did not count as work, unless it was controlled by, required by, and for the benefit of an employer, like traveling through a coal mine. For example, in, Anderson v. Mt. Clemens Pottery Co. a majority of five to two justices held that employees had to be paid for the long walk to work through an employer's Mount Clemens Pottery Co facility. According to Murphy J this time, and time setting up workstations, involved "exertion of a physical nature, controlled or required by the employer and pursued necessarily and primarily for the employer's benefit." In Armour & Co. v. Wantock firefighters claimed they should be fully paid while on call at their station for fires. The Supreme Court held that, even though the firefighters could sleep or play cards, because "eadiness to serve may be hired quite as much as service itself" and time waiting on call was "a benefit to the employer". By contrast, in 1992 the Sixth Circuit controversially held that needing to be infrequently available by phone or pager, where movement was not restricted, was not working time. Time spent doing unusual cleaning, for instance showering off toxic substances, does count as working time, and so does time putting on special protective gear. Under §207(e) pay for overtime should be one and a half times the regular pay. In Walling v. Helmerich & Payne, Inc., the Supreme Court held that an employer's scheme of paying lower wages in the morning, and higher wages in the afternoon, to argue that overtime only needed to be calculated on top of (lower) morning wages was unlawful. Overtime has to be calculated based on the average regular pay. However, in Christensen v. Harris County six Supreme Court judges held that police in Harris County, Texas, could be forced to use up their accumulated "compensatory time" (allowing time off with full pay) before claiming overtime. Writing for the dissent, Stevens J said the majority had misconstrued §207(o)(2), which requires an "agreement" between employers, unions or employees on the applicable rules, and the Texas police had not agreed. Third, §203(m) allows employers to deduct sums from wages for food or housing that is "customarily furnished" for employees. The secretary of labor may determine what counts as fair value. Most problematically, outside states that have banned the practice, they may deduct money from a "tipped employee" for money over the "cash wage required to be paid such an employee on August 20, 1996"—and this was $2.13 per hour. If an employee does not earn enough in tips, the employer must still pay the $7.25 minimum wage. But this means in many states tips do not go to workers: tips are taken by employers to subsidize low pay. Under FLSA 1938 §216(b)-(c) the secretary of state can enforce the law, or individuals can claim on their own behalf. Federal enforcement is rare, so most employees are successful if they are in a labor union. The Consumer Credit Protection Act of 1968 limits deductions or "garnishments" by employers to 25 per cent of wages, though many states are considerably more protective. Finally, under the Portal to Portal Act of 1947, where Congress limited the minimum wage laws in a range of ways, §254 puts a two-year time limit on enforcing claims, or three years if an employing entity is guilty of a willful violation.

- Income tax in the United States

- Legal history of income tax in the United States

- State income tax

- Payroll tax, Federal Insurance Contributions Act tax

Working time and family care

| Working time law sources | |

|---|---|

| ILO Holidays with Pay Convention 1970 (no 132) | |

| 5 USC §§6103-6304 | |

| Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938, 29 USC §207 | |

| Lochner v New York, 300 US 379 (1905) | |

| West Coast Hotel Co v Parrish, 300 US 379 (1937) | |

| Family and Medical Leave Act of 1993, 29 USC §2601 | |

| Ragsdale v Wolverine World Wide, Inc, 535 US 81 (2002) | |

| See US labor law and Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 |

People in the United States work among the longest hours per week in the industrialized world, and have the least annual leave. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights of 1948 article 24 states: "Everyone has the right to rest and leisure, including reasonable limitation of working hours and periodic holidays with pay." However, there is no general federal or state legislation requiring paid annual leave. Title 5 of the United States Code §6103 specifies ten public holidays for federal government employees, and provides that holidays will be paid. Many states do the same, however, no state law requires private sector employers to provide paid holidays. Many private employers follow the norms of federal and state government, but the right to annual leave, if any, will depend upon collective agreements and individual employment contracts. State law proposals have been made to introduce paid annual leave. A 2014 Washington Bill from United States House of Representatives member Gael Tarleton would have required a minimum of 3 weeks of paid holidays each year to employees in businesses of over 20 staff, after 3 years work. Under the International Labour Organization Holidays with Pay Convention 1970 three weeks is the bare minimum. The bill did not receive enough votes. By contrast, employees in all European Union countries have the right to at least 4 weeks (i.e. 28 days) of paid annual leave each year. Furthermore, there is no federal or state law on limits to the length of the working week. Instead, the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 §207 creates a financial disincentive to longer working hours. Under the heading "Maximum hours", §207 states that time and a half pay must be given to employees working more than 40 hours in a week. It does not, however, set an actual limit, and there are at least 30 exceptions for categories of employee which do not receive overtime pay. Shorter working time was one of the labor movement's original demands. From the first decades of the 20th century, collective bargaining produced the practice of having, and the word for, a two-day "weekend". State legislation to limit working time was, however, suppressed by the US Supreme Court in Lochner v. New York. The New York State Legislature had passed the Bakeshop Act of 1895, which limited work in bakeries to 10 hours a day or 60 hours a week, to improve health, safety and people's living conditions. After being prosecuted for making his staff work longer in his Utica, Mr Lochner claimed that the law violated the Fourteenth Amendment on "due process". Despite the dissent of four judges, a majority of five judges held that the law was unconstitutional. The Supreme Court, however, did uphold Utah's mine workday statute in 1898. The Mississippi State Supreme Court upheld a ten hour workday statute in 1912 when it ruled against the due process arguments of an interstate lumber company. The whole Lochner era of jurisprudence was reversed by the US Supreme Court in 1937, but experimentation to improve working time rights, and "work-life balance" has not yet recovered.

Just as there are no rights to paid annual leave or maximum hours, there are no rights to paid time off for child care or family leave in federal law. There are minimal rights in some states. Most collective agreements, and many individual contracts, provide paid time off, but employees who lack bargaining power will often get none. There are, however, limited federal rights to unpaid leave for family and medical reasons. The Family and Medical Leave Act of 1993 generally applies to employers of 50 or more employees in 20 weeks of the last year, and gives rights to employees who have worked over 12 months and 1250 hours in the last year. Employees can have up to 12 weeks of unpaid leave for child birth, adoption, to care for a close relative in poor health, or because of an employee's own poor health. Child care leave should be taken in one lump, unless agreed otherwise. Employees must give notice of 30 days to employers if birth or adoption is "foreseeable", and for serious health conditions if practicable. Treatments should be arranged "so as not to disrupt unduly the operations of the employer" according to medical advice. Employers must provide benefits during the unpaid leave. Under §2652(b) states are empowered to provide "greater family or medical leave rights". In 2016 California, New Jersey, Rhode Island and New York had laws for paid family leave rights. Under §2612(2)(A) an employer can make an employee substitute the right to 12 unpaid weeks of leave for "accrued paid vacation leave, personal leave or family leave" in an employer's personnel policy. Originally the Department of Labor had a penalty to make employers notify employees that this might happen. However, five judges in the US Supreme Court in Ragsdale v. Wolverine World Wide, Inc. held that the statute precluded the right of the Department of Labor to do so. Four dissenting judges would have held that nothing prevented the rule, and it was the Department of Labor's job to enforce the law. After unpaid leave, an employee generally has the right to return to his or her job, except for employees who are in the top 10% of highest paid and the employer can argue refusal "is necessary to prevent substantial and grievous economic injury to the operations of the employer." Employees or the secretary of labor can bring enforcement actions, but there is no right to a jury for reinstatement claims. Employees can seek damages for lost wages and benefits, or the cost of child care, plus an equal amount of liquidated damages unless an employer can show it acted in good faith and reasonable cause to believe it was not breaking the law. There is a two-year limit on bringing claims, or three years for willful violations. Despite the lack of rights to leave, there is no right to free child care or day care. This has encouraged several proposals to create a public system of free child care, or for the government to subsize parents' costs.

Pensions

| Pension sources | |

|---|---|

| Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974 §1003(a) | |

| ERISA 1974 §§1022-1133 and 1052-9 | |

| Guidry v Sheet Metal Workers Pension Fund 493 US 365 (1990) | |

| Lockheed Corp v Spink 517 US 882 (1996) | |

| Mead Corp v Tilley 490 US 714 (1989) | |

| ERISA 1974 §§1081-1102 and 1140 | |

| Peacock v Thomas 516 US 349 (1996) | |

| ERISA 1974 §§1102-1132 | |

| Donovan v Bierwirth 680 F2d 263 (1982) | |

| Varity Corp v Howe 516 US 489 (1996) | |

| Local 144, Nursing Home Pension v Demisay 508 US 581 (1992) | |

| Labor Management Reporting and Disc Act of 1959 §§401-531 | |

| ERISA 1974 §1144 | |

| Shaw v Delta Air Lines, Inc 463 US 85 (1983) | |

| Metropolitan Life Insurance Co v Massachusetts 471 US 724 (1985) | |

| FMC Corp v Holliday 498 US 52 (1990) | |

| Ingersoll-Rand Co v McClendon 498 US 133 (1990) | |

| Egelhoff v Egelhoff 532 US 141 (2001) | |

| Rush Prudential HMO, Inc. v Moran 536 US 355 (2002) | |

| ERISA 1974 §§1102-3 and LMRA 1947 §186(c)(5)(B) | |

| NLRB v Amax Coal Co 453 US 322 (1981) | |

| See US labor law and pensions |

In the early 20th century, the possibility of having a "retirement" became real as people lived longer, and believed the elderly should not have to work or rely on charity until they died. The law maintains an income in retirement in three ways (1) through a public social security program created by the Social Security Act of 1935, (2) occupational pensions managed through the employment relationship, and (3) private pensions or life insurance that individuals buy themselves. At work, most occupational pension schemes originally resulted from collective bargaining during the 1920s and 1930s. Unions usually bargained for employers across a sector to pool funds, so that employees could keep their pensions if they moved jobs. Multi-employer retirement plans, set up by collective agreement became known as "Taft–Hartley plans" after the Taft–Hartley Act of 194] required joint management of funds by employees and employers. Many employers also voluntarily choose to provide pensions. For example, the pension for professors, now called TIAA, was established on the initiative of Andrew Carnegie in 1918 with the express requirement for participants to have voting rights for the plan trustees. These could be collective and defined benefit schemes: a percentage of one's income (e.g. 67%) is replaced for retirement, however long the person lives. But more recently more employers have only provided individual "401(k)" plans. These are named after the Internal Revenue Code §401(k), which allows employers and employees to pay no tax on money that is saved in the fund, until an employee retires. The same tax deferral rule applies to all pensions. But unlike a "defined benefit" plan, a 401(k) only contains whatever the employer and employee contribute. It will run out if a person lives too long, meaning the retiree may only have minimum social security. The Pension Protection Act of 2006 §902 codified a model for employers to automatically enroll their employees in a pension, with a right to opt out. However, there is no right to an occupational pension. The Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974 does create a series of rights for employees if one is set up. It also applies to health care or any other "employee benefit" plan.

Five main rights for beneficiaries in ERISA 1974 include information, funding, vesting, anti-discrimination, and fiduciary duties. First, each beneficiary should receive a "summary plan description" in 90 days of joining, plans must file annual reports with the secretary of labor, and if beneficiaries make claims any refusal must be justified with a "full and fair review". If the "summary plan description" is more beneficial than the actual plan documents, because the pension fund makes a mistake, a beneficiary may enforce the terms of either. If an employer has pension or other plans, all employees must be entitled to participate after at longest 12 months, if working over 1000 hours. Second, all promises must be funded in advance. The Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation was established by the federal government to be an insurer of last resort, but only up to $60,136 per year for each employer. Third, employees' benefits usually cannot be taken away (they "vest") after 5 years, and contributions must accrue (i.e. the employee owns contributions) at a proportionate rate. If employers and pension funds merge, there can be no reduction in benefits, and if an employee goes bankrupt their creditors cannot take their occupational pension. However, the US Supreme Court has enabled benefits to be withdrawn by employers simply amending plans. In Lockheed Corp. v. Spink a majority of seven judges held that an employer could alter a plan, to deprive a 61-year-old man of full benefits when he was reemployed, unbound by fiduciary duties to preserve what an employee had originally been promised. In dissent, Breyer J and Souter J reserved any view on such "highly technical, important matters". Steps to terminate a plan depend on whether it is individual, or multi-employer, and Mead Corp. v. Tilley a majority of the US Supreme Court held that employers could recoup excess benefits paid into pension plans after PBGC conditions are fulfilled. Stevens J, dissenting, contended that all contingent and future liabilities must be satisfied. Fourth, as a general principle, employees or beneficiaries cannot suffer any discrimination or detriment for "the attainment of any right" under a plan. Fifth, managers are bound by responsibilities of competence and loyalty, called "fiduciary duties". Under §1102, a fiduciary is anyone who administers a plan, its trustees, and investment managers who are delegated control. Under §1104, fiduciaries must follow a "prudent" person standard, involving three main components. First, a fiduciary must act "in accordance with the documents and instruments governing the plan". Second, they must act with "care, skill and diligence", including "diversifying the investments of the plan" to "minimize the risk of large losses". Liability for carelessness extends to making misleading statements about benefits, and have been interpreted by the Department of Labor to involve a duty to vote on proxies when corporate stocks are purchased, and publicizing a statement of investment policy. Third, and codifying fundamental equitable principles, a fiduciary must avoid any possibility of a conflict of interest. Fiduciaries must act "solely in the interest of the participants ... for the exclusive purpose of providing benefits" with "reasonable expenses", and specifically avoiding self-dealing with a related "party in interest". For example, in Donovan v. Bierwirth, the Second Circuit held that trustees of a pension which owned shares in the employees' company as a takeover bid was launched, because they faced a potential conflict of interest, had to get independent legal advice on how to vote, or possibly abstain. Remedies for these duties have, however, been restricted by the Supreme Court to disfavor damages. In these fields, according to §1144, ERISA 1974 will "supersede any and all State laws insofar as they may now or hereafter relate to any employee benefit plan". ERISA did not, therefore, follow the model of the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 or the Family and Medical Leave Act of 1993, which encourage states to legislate for improved protection for employees, beyond the minimum. The preemption rule led the US Supreme Court to strike down a New York that required giving benefits to pregnant employees in ERISA plans. It held a case under Texas law for damages for denying vesting of benefits was preempted, so the claimant only had ERISA remedies. It struck down a Washington law which altered who would receive life insurance designation on death. However, under §1144(b)(2)(A) this does not affect 'any law of any State which regulates insurance, banking, or securities.' So, the Supreme Court has also held valid a Massachusetts law requiring mental health to be covered by employer group health policies. But it struck down a Pennsylvania statute which prohibited employers becoming subrogated to (potentially more valuable) claims of employees for insurance after accidents. Yet more recently, the court has shown a greater willingness to prevent laws being preempted, however the courts have not yet adopted the principle that state law is not preempted or "superseded" if it is more protective to employees than a federal minimum.

The most important rights that ERISA 1974 did not cover were who controls investments and securities that beneficiaries' retirement savings buy. The largest form of retirement fund has become the 401(k). This is often an individual account that an employer sets up, and an investment management firm, such as Vanguard, Fidelity, Morgan Stanley or BlackRock, is then delegated the task of trading fund assets. Usually they also vote on corporate shares, assisted by a "proxy advice" firm such as ISS or Glass Lewis. Under ERISA 1974 §1102(a), a plan must merely have named fiduciaries who have "authority to control and manage the operation and administration of the plan", selected by "an employer or employee organization" or both jointly. Usually these fiduciaries or trustees, will delegate management to a professional firm, particularly because under §1105(d), if they do so, they will not be liable for an investment manager's breaches of duty. These investment managers buy a range of assets, particularly corporate stocks which have voting rights, as well as government bonds, corporate bonds, commodities, real estate or derivatives. Rights on those assets are in practice monopolized by investment managers, unless pension funds have organized to take voting in house, or to instruct their investment managers. Two main types of pension fund to do this are union organized Taft–Hartley plans, and state public pension plans. Under the amended National Labor Relations Act of 1935 §302(c)(5)(B) a union bargained plan has to be jointly managed by representatives of employers and employees. Although many local pension funds are not consolidated and have had critical funding notices from the Department of Labor, more funds with employee representation ensure that corporate voting rights are cast according to the preferences of their members. State public pensions are often larger, and have greater bargaining power to use on their members' behalf. State pension schemes invariably disclose the way trustees are selected. In 2005, on average more than a third of trustees were elected by employees or beneficiaries. For example, the California Government Code §20090 requires that its public employee pension fund, CalPERS has 13 members on its board, 6 elected by employees and beneficiaries. However, only pension funds of sufficient size have acted to replace investment manager voting. Furthermore, no general legislation requires voting rights for employees in pension funds, despite several proposals. For example, the Workplace Democracy Act of 1999, sponsored by Bernie Sanders then in the US House of Representatives, would have required all single employer pension plans to have trustees appointed equally by employers and employee representatives. There is, furthermore, currently no legislation to stop investment managers voting with other people's money as the Dodd–Frank Act of 2010 §957 banned broker-dealers voting on significant issues without instructions. This means votes in the largest corporations that people's retirement savings buy are overwhelmingly exercised by investment managers, whose interests potentially conflict with the interests of beneficiaries' on labor rights, fair pay, job security, or pension policy.

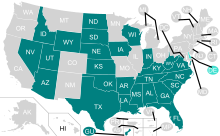

Health and safety

Main articles: Occupational Safety and Health Act 1970, US tort law, and Affordable Care ActThe Occupational Safety and Health Act, signed into law in 1970 by President Richard Nixon, creates specific standards for workplace safety. The act has spawned years of litigation by industry groups that have challenged the standards limiting the amount of permitted exposure to chemicals such as benzene. The Act also provides for protection for "whistleblowers" who complain to governmental authorities about unsafe conditions while allowing workers the right to refuse to work under unsafe conditions in certain circumstances. The act allows states to take over the administration of OSHA in their jurisdictions, so long as they adopt state laws at least as protective of workers' rights as under federal law. More than half of the states have done so.

Civil liberties

- Pickering v. Board of Education, 391 US 563 (1968) 8 to 1, a public school teacher was dismissed for writing a letter to a newspaper that criticized the way the school board was raising money. This violated the First Amendment and the Fourteenth Amendment

- Connick v. Myers, 461 U.S. 138 (1983) 5 to 4, a public attorney employee was not unlawfully dismissed after distributing a questionnaire to other staff on a supervisor's management practices after she was transferred under protest. In dissent, Brennan J held that all the matters were of public concern and should therefore be protected by the First Amendment

- Rankin v. McPherson, 483 U.S. 378 (1987) 5 to 4, a Texas deputy constable had a First Amendment right to say, after the assassination attempt on Ronald Reagan "Shoot, if they go for him again, I hope they get him." Dismissal was unlawful and she had to be reinstated because even extreme comments (except potentially advocating actual murder) against a political figure should be protected. She could not be fired for merely exercising a right in the Constitution.

- Waters v. Churchill, 511 U.S. 661 (1994) 7 to 2, a public hospital nurse stating, outside work at dinner, that the cross-training policies of the hospital were flawed, could be dismissed without any violation of the First Amendment because it could be seen as interfering with the employer's operations

- Garcetti v. Ceballos, 547 U.S. 410 (2006) 5 to 4, no right against dismissal or protected speech when the speech relates to a matter in one's profession

- Employee Polygraph Protection Act (1988) outlawed the use of lie detectors by private employers except in narrowly prescribed circumstances

- Whistleblower Protection Act (1989)

- Huffman v. Office of Personnel Management, 263 F.3d 1341 (Fed. Cir. 2001)

- O'Connor v. Ortega, 480 U.S. 709 (1987) searches in the workplace

- City of Ontario v. Quon, 130 S.Ct. 2619, (2010) the right of privacy did not extend to employer owned electronic devices so an employee could be dismissed for sending sexually explicit messages from an employer owned pager.

- Heffernan v. City of Paterson, 578 US __ (2016)

Workplace participation

See also: Collective bargaining, US corporate law, Codetermination, and Work council

The central right in labor law, beyond minimum standards for pay, hours, pensions, safety or privacy, is to participate and vote in workplace governance. The American model developed from the Clayton Antitrust Act of 1914, which declared the "labor of a human being is not a commodity or article of commerce" and aimed to take workplace relations out of the reach of courts hostile to collective bargaining. Lacking success, the National Labor Relations Act of 1935 changed the basic model, which remained through the 20th century. Reflecting the "inequality of bargaining power between employees ... and employers who are organized in the corporate or other forms of ownership association", the NLRA 1935 codified basic rights of employees to organize a union, requires employers to bargain in good faith (at least on paper) after a union has majority support, binds employers to collective agreements, and protects the right to take collective action including a strike. Union membership, collective bargaining, and standards of living all increased rapidly until Congress forced through the Taft–Hartley Act of 1947. Its amendments enabled states to pass laws restricting agreements for all employees in a workplace to be unionized, prohibited collective action against associated employers, and introduced a list of unfair labor practices for unions, as well as employers. Since then, the US Supreme Court chose to develop a doctrine that the rules in the NLRA 1935 preempted any other state rules if an activity was "arguably subject" to its rights and duties. While states were inhibited from acting as "laboratories of democracy", and particularly as unions were targeted from 1980 and membership fell, the NLRA 1935 has been criticized as a "failed statute" as US labor law "ossified". This has led to more innovative experiments among states, progressive corporations and unions to create direct participation rights, including the right to vote for or codetermine directors of corporate boards, and elect work councils with binding rights on workplace issues.

Labor unions

| Sources on labor unions | |

|---|---|

| First Amendment to the US Constitution | |

| ILO Freedom of Association Convention 1948 (c 87) | |

| Labor Management Reporting and Disclosure Act of 1959 | |

| Trbovich v. United Mine Workers, 404 U.S. 528 (1972) | |

| Dunlop v. Bachowski, 421 U.S. 560 (1975) | |

| De Veau v. Braisted, 363 U.S. 144 (1960) | |

| Brown v. Hotel and Rest. Employees, 468 U.S. 491 (1984) | |

| Machinists v. Street, 367 U.S. 740 (1961) | |

| CWA v. Beck, 487 U.S. 735 (1988) | |

| Locke v. Karass, 555 U.S. 207 (2009) | |

| Abood v. Detroit Board of Education, 431 U.S. 209 (1977) | |

| Davenport v. Washington Education Ass'n, 551 U.S. 177 (2007) | |

| Janus v. AFSCME , 585 U.S. ___ (2018) | |

| See US labor and unions |

Freedom of association in labor unions has always been fundamental to the development of democratic society, and is protected by the First Amendment to the Constitution. In early colonial history, labor unions were routinely suppressed by the government. Recorded instances include cart drivers being fined for striking in 1677 in New York City, and carpenters prosecuted as criminals for striking in Savannah, Georgia in 1746. After the American Revolution, however, courts departed from repressive elements of English common law. The first reported case, Commonwealth v. Pullis in 1806 did find shoemakers in Philadelphia guilty of "a combination to raise their wages". Nevertheless, unions continued, and the first federation of trade unions was formed in 1834, the National Trades' Union, with the primary aim of a 10-hour working day. In 1842 the Supreme Court of Massachusetts held in Commonwealth v. Hunt that a strike by the Boston Journeymen Bootmakers' Society for higher wages was lawful. Chief Justice Shaw held that people "are free to work for whom they please, or not to work, if they so prefer" and "to agree together to exercise their own acknowledged rights". The abolition of slavery by Abraham Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation during the American Civil War was necessary to create genuine rights to organize, but was not sufficient to ensure freedom of association. Using the Sherman Act of 1890, which was intended to break up business cartels, the Supreme Court imposed an injunction on striking workers of the Pullman Company, and imprisoned the leader, and future presidential candidate, Eugene Debs. The court also enabled unions to be sued for triple damages in Loewe v. Lawlor, a case involving a hat maker union in Danbury, Connecticut. The president and United States Congress responded by passing the Clayton Act of 1914 to take labor out of antitrust law. Then, after the Great Depression passed the National Labor Relations Act of 1935 to positively protect the right to organize and take collective action. After that, the law increasingly turned to regulate unions' internal affairs. The Taft–Hartley Act of 1947 regulated how members can join a union, and the Labor Management Reporting and Disclosure Act of 1959 created a "bill of rights" for union members.

While union governance is founded upon freedom of association, the law requires basic standards of democracy and accountability to ensure members are truly free in shaping their associations. Fundamentally, all unions are democratic organizations, but they divide between those where members elect delegates, who in turn choose the executive, and those where members directly elect the executive. In 1957, after the McClellan Committee of the US Senate found evidence of two rival Teamsters Union executives, Jimmy Hoffa and Dave Beck, falsifying delegate vote counts and stealing union funds, Congress passed the Labor Management Reporting and Disclosure Act of 1959. Under § 411, every member has the right to vote, attend meetings, speak freely and organize, not have fees raised without a vote, not be deprived of the right to sue, or be suspended unjustly. Under § 431, unions should file their constitutions and bylaws with the secretary of labor and be accessible by members: today union constitutions are online. Under § 481 elections must occur at least every 5 years, and local officers every 3 years, by secret ballot. Additionally, state law may bar union officials who have prior convictions for felonies from holding office. As a response to the Hoffa and Beck scandals, there is also an express fiduciary duty on union officers for members' money, limits on loans to executives, requirements for bonds for handling money, and up to a $10,000 fine or up to 5 years prison for embezzlement. These rules, however, restated most of what was already the law, and codified principles of governance that unions already undertook. On the other hand, under § 501(b) to bring a lawsuit, a union member must first make a demand on the executive to correct wrongdoing before any claim can be made to a court, even for misapplication of funds, and potentially wait four months' time. The Supreme Court has held that union members can intervene in enforcement proceedings brought by the US Department of Labor. Federal courts may review decisions by the Department to proceed with any prosecutions. The range of rights, and the level of enforcement has meant that labor unions display significantly higher standards of accountability, with fewer scandals, than corporations or financial institutions.

Beyond members rights within a labor union, the most controversial issue has been how people become members in unions. This affects union membership numbers, and whether labor rights are promoted or suppressed in democratic politics. Historically, unions made collective agreements with employers that all new workers would have to join the union. This was to prevent employers trying to dilute and divide union support, and ultimately refuse to improve wages and conditions in collective bargaining. However, after the Taft–Hartley Act of 1947, the National Labor Relations Act of 1935 § 158(a)(3) was amended to ban employers from refusing to hire a non-union employee. An employee can be required to join the union (if such a collective agreement is in place) after 30 days. But § 164(b) was added to codify a right of states to pass so called "right to work laws" that prohibit unions making collective agreements to register all workers as union members, or collect fees for the service of collective bargaining. Over time, as more states with Republican governments passed laws restricting union membership agreements, there has been a significant decline of union density. Unions have not, however, yet experimented with agreements to automatically enroll employees in unions with a right to opt out. In International Ass'n of Machinists v. Street, a majority of the US Supreme Court, against three dissenting justices, held that the First Amendment precluded making an employee become a union member against their will, but it would be lawful to collect fees to reflect the benefits from collective bargaining: fees could not be used for spending on political activities without the member's consent. Unions have always been entitled to publicly campaign for members of Congress or presidential candidates that support labor rights. But the urgency of political spending was raised when in 1976 Buckley v. Valeo decided, over powerful dissents of White J and Marshall J, that candidates could spend unlimited money on their own political campaign, and then in First National Bank of Boston v. Bellotti, that corporations could engage in election spending. In 2010, over four dissenting justices, Citizens United v. FEC held there could be essentially no limits to corporate spending. By contrast, every other democratic country caps spending (usually as well as regulating donations) as the original Federal Election Campaign Act of 1971 had intended to do. A unanimous court held in Abood v. Detroit Board of Education that union security agreements to collect fees from non-members were also allowed in the public sector. However, in Harris v. Quinn five US Supreme Court judges reversed this ruling apparently banning public sector union security agreements, and were about to do the same for all unions in Friedrichs v. California Teachers Association until Scalia J died, halting an anti-labor majority on the Supreme Court. In 2018, Janus v. AFSCME the Supreme Court held by 5 to 4 that collecting mandatory union fees from public sector employees violated the First Amendment. The dissenting judges argued that union fees merely paid for benefits of collective bargaining that non-members otherwise received for free. These factors led campaign finance reform to be one of the most important issues in the 2016 US Presidential election, for the future of the labor movement, and democratic life.

Collective bargaining

| Collective bargain sources | |

|---|---|

| First Amendment | |

| ILO Right to Organise and Collective Bargaining Convention, 1949 c 98 | |

| National Labor Relations Act of 1935 §§157-159 and 185 | |

| NLRB v. Borg-Warner Corp. 356 US 342 (1958) | |

| First National Maintenance Corp. v. NLRB 452 US 666 (1981) | |

| JI Case Co v. National Labor Relations Board 321 US 332 (1944) | |