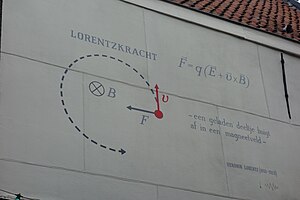

In physics, specifically in electromagnetism, the Lorentz force law is the combination of electric and magnetic force on a point charge due to electromagnetic fields. The Lorentz force, on the other hand, is a physical effect that occurs in the vicinity of electrically neutral, current-carrying conductors causing moving electrical charges to experience a magnetic force.

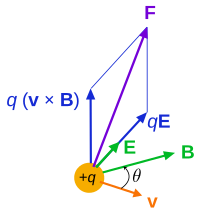

The Lorentz force law states that a particle of charge q moving with a velocity v in an electric field E and a magnetic field B experiences a force (in SI units) of It says that the electromagnetic force on a charge q is a combination of (1) a force in the direction of the electric field E (proportional to the magnitude of the field and the quantity of charge), and (2) a force at right angles to both the magnetic field B and the velocity v of the charge (proportional to the magnitude of the field, the charge, and the velocity).

Variations on this basic formula describe the magnetic force on a current-carrying wire (sometimes called Laplace force), the electromotive force in a wire loop moving through a magnetic field (an aspect of Faraday's law of induction), and the force on a moving charged particle.

Historians suggest that the law is implicit in a paper by James Clerk Maxwell, published in 1865. Hendrik Lorentz arrived at a complete derivation in 1895, identifying the contribution of the electric force a few years after Oliver Heaviside correctly identified the contribution of the magnetic force.

Lorentz force law as the definition of E and B

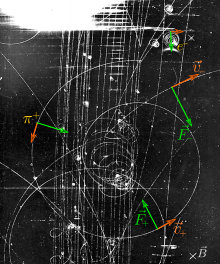

Trajectory of a particle with a positive or negative charge q under the influence of a magnetic field B, which is directed perpendicularly out of the screen

Trajectory of a particle with a positive or negative charge q under the influence of a magnetic field B, which is directed perpendicularly out of the screen Beam of electrons moving in a circle, due to the presence of a magnetic field. Purple light revealing the electron's path in this Teltron tube is created by the electrons colliding with gas molecules.Charged particles experiencing the Lorentz force

Beam of electrons moving in a circle, due to the presence of a magnetic field. Purple light revealing the electron's path in this Teltron tube is created by the electrons colliding with gas molecules.Charged particles experiencing the Lorentz force

In many textbook treatments of classical electromagnetism, the Lorentz force law is used as the definition of the electric and magnetic fields E and B. To be specific, the Lorentz force is understood to be the following empirical statement:

The electromagnetic force F on a test charge at a given point and time is a certain function of its charge q and velocity v, which can be parameterized by exactly two vectors E and B, in the functional form:

This is valid, even for particles approaching the speed of light (that is, magnitude of v, |v| ≈ c). So the two vector fields E and B are thereby defined throughout space and time, and these are called the "electric field" and "magnetic field". The fields are defined everywhere in space and time with respect to what force a test charge would receive regardless of whether a charge is present to experience the force.

Physical interpretation of the Lorentz force

Coulomb's law is only valid for point charges at rest. In fact, the electromagnetic force between two point charges depends not only on the distance but also on the relative velocity. For small relative velocities and very small accelerations, instead of the Coulomb force, the Weber force can be applied. The sum of the Weber forces of all charge carriers in a closed DC loop on a single test charge produces – regardless of the shape of the current loop – the Lorentz force.

The interpretation of magnetism by means of a modified Coulomb law was first proposed by Carl Friedrich Gauss. In 1835, Gauss assumed that each segment of a DC loop contains an equal number of negative and positive point charges that move at different speeds. If Coulomb's law were completely correct, no force should act between any two short segments of such current loops. However, around 1825, André-Marie Ampère demonstrated experimentally that this is not the case. Ampère also formulated a force law. Based on this law, Gauss concluded that the electromagnetic force between two point charges depends not only on the distance but also on the relative velocity.

The Weber force is a central force and complies with Newton's third law. This demonstrates not only the conservation of momentum but also that the conservation of energy and the conservation of angular momentum apply. Weber electrodynamics is only a quasistatic approximation, i.e. it should not be used for higher velocities and accelerations. However, the Weber force illustrates that the Lorentz force can be traced back to central forces between numerous point-like charge carriers.

Equation

Charged particle

The force F acting on a particle of electric charge q with instantaneous velocity v, due to an external electric field E and magnetic field B, is given by (SI definition of quantities):

where × is the vector cross product (all boldface quantities are vectors). In terms of Cartesian components, we have:

In general, the electric and magnetic fields are functions of the position and time. Therefore, explicitly, the Lorentz force can be written as: in which r is the position vector of the charged particle, t is time, and the overdot is a time derivative.

A positively charged particle will be accelerated in the same linear orientation as the E field, but will curve perpendicularly to both the instantaneous velocity vector v and the B field according to the right-hand rule (in detail, if the fingers of the right hand are extended to point in the direction of v and are then curled to point in the direction of B, then the extended thumb will point in the direction of F).

The term qE is called the electric force, while the term q(v × B) is called the magnetic force. According to some definitions, the term "Lorentz force" refers specifically to the formula for the magnetic force, with the total electromagnetic force (including the electric force) given some other (nonstandard) name. This article will not follow this nomenclature: In what follows, the term Lorentz force will refer to the expression for the total force.

The magnetic force component of the Lorentz force manifests itself as the force that acts on a current-carrying wire in a magnetic field. In that context, it is also called the Laplace force.

The Lorentz force is a force exerted by the electromagnetic field on the charged particle, that is, it is the rate at which linear momentum is transferred from the electromagnetic field to the particle. Associated with it is the power which is the rate at which energy is transferred from the electromagnetic field to the particle. That power is Notice that the magnetic field does not contribute to the power because the magnetic force is always perpendicular to the velocity of the particle.

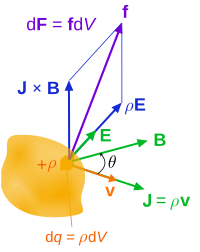

Continuous charge distribution

For a continuous charge distribution in motion, the Lorentz force equation becomes: where is the force on a small piece of the charge distribution with charge . If both sides of this equation are divided by the volume of this small piece of the charge distribution , the result is: where is the force density (force per unit volume) and is the charge density (charge per unit volume). Next, the current density corresponding to the motion of the charge continuum is so the continuous analogue to the equation is

The total force is the volume integral over the charge distribution:

By eliminating and , using Maxwell's equations, and manipulating using the theorems of vector calculus, this form of the equation can be used to derive the Maxwell stress tensor , in turn this can be combined with the Poynting vector to obtain the electromagnetic stress–energy tensor T used in general relativity.

In terms of and , another way to write the Lorentz force (per unit volume) is where is the speed of light and ∇· denotes the divergence of a tensor field. Rather than the amount of charge and its velocity in electric and magnetic fields, this equation relates the energy flux (flow of energy per unit time per unit distance) in the fields to the force exerted on a charge distribution. See Covariant formulation of classical electromagnetism for more details.

The density of power associated with the Lorentz force in a material medium is

If we separate the total charge and total current into their free and bound parts, we get that the density of the Lorentz force is

where: is the density of free charge; is the polarization density; is the density of free current; and is the magnetization density. In this way, the Lorentz force can explain the torque applied to a permanent magnet by the magnetic field. The density of the associated power is

Formulation in the Gaussian system

The above-mentioned formulae use the conventions for the definition of the electric and magnetic field used with the SI, which is the most common. However, other conventions with the same physics (i.e. forces on e.g. an electron) are possible and used. In the conventions used with the older CGS-Gaussian units, which are somewhat more common among some theoretical physicists as well as condensed matter experimentalists, one has instead where c is the speed of light. Although this equation looks slightly different, it is equivalent, since one has the following relations: where ε0 is the vacuum permittivity and μ0 the vacuum permeability. In practice, the subscripts "G" and "SI" are omitted, and the used convention (and unit) must be determined from context.

History

Early attempts to quantitatively describe the electromagnetic force were made in the mid-18th century. It was proposed that the force on magnetic poles, by Johann Tobias Mayer and others in 1760, and electrically charged objects, by Henry Cavendish in 1762, obeyed an inverse-square law. However, in both cases the experimental proof was neither complete nor conclusive. It was not until 1784 when Charles-Augustin de Coulomb, using a torsion balance, was able to definitively show through experiment that this was true. Soon after the discovery in 1820 by Hans Christian Ørsted that a magnetic needle is acted on by a voltaic current, André-Marie Ampère that same year was able to devise through experimentation the formula for the angular dependence of the force between two current elements. In all these descriptions, the force was always described in terms of the properties of the matter involved and the distances between two masses or charges rather than in terms of electric and magnetic fields.

The modern concept of electric and magnetic fields first arose in the theories of Michael Faraday, particularly his idea of lines of force, later to be given full mathematical description by Lord Kelvin and James Clerk Maxwell. From a modern perspective it is possible to identify in Maxwell's 1865 formulation of his field equations a form of the Lorentz force equation in relation to electric currents, although in the time of Maxwell it was not evident how his equations related to the forces on moving charged objects. J. J. Thomson was the first to attempt to derive from Maxwell's field equations the electromagnetic forces on a moving charged object in terms of the object's properties and external fields. Interested in determining the electromagnetic behavior of the charged particles in cathode rays, Thomson published a paper in 1881 wherein he gave the force on the particles due to an external magnetic field as Thomson derived the correct basic form of the formula, but, because of some miscalculations and an incomplete description of the displacement current, included an incorrect scale-factor of a half in front of the formula. Oliver Heaviside invented the modern vector notation and applied it to Maxwell's field equations; he also (in 1885 and 1889) had fixed the mistakes of Thomson's derivation and arrived at the correct form of the magnetic force on a moving charged object. Finally, in 1895, Hendrik Lorentz derived the modern form of the formula for the electromagnetic force which includes the contributions to the total force from both the electric and the magnetic fields. Lorentz began by abandoning the Maxwellian descriptions of the ether and conduction. Instead, Lorentz made a distinction between matter and the luminiferous aether and sought to apply the Maxwell equations at a microscopic scale. Using Heaviside's version of the Maxwell equations for a stationary ether and applying Lagrangian mechanics (see below), Lorentz arrived at the correct and complete form of the force law that now bears his name.

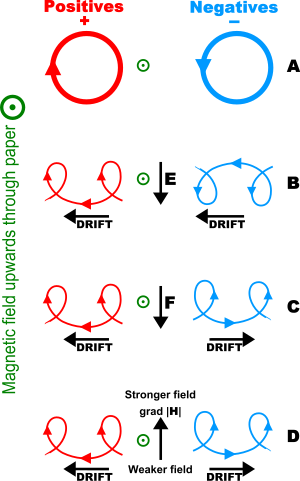

Trajectories of particles due to the Lorentz force

Main article: Guiding center

In many cases of practical interest, the motion in a magnetic field of an electrically charged particle (such as an electron or ion in a plasma) can be treated as the superposition of a relatively fast circular motion around a point called the guiding center and a relatively slow drift of this point. The drift speeds may differ for various species depending on their charge states, masses, or temperatures, possibly resulting in electric currents or chemical separation.

Significance of the Lorentz force

While the modern Maxwell's equations describe how electrically charged particles and currents or moving charged particles give rise to electric and magnetic fields, the Lorentz force law completes that picture by describing the force acting on a moving point charge q in the presence of electromagnetic fields. The Lorentz force law describes the effect of E and B upon a point charge, but such electromagnetic forces are not the entire picture. Charged particles are possibly coupled to other forces, notably gravity and nuclear forces. Thus, Maxwell's equations do not stand separate from other physical laws, but are coupled to them via the charge and current densities. The response of a point charge to the Lorentz law is one aspect; the generation of E and B by currents and charges is another.

In real materials the Lorentz force is inadequate to describe the collective behavior of charged particles, both in principle and as a matter of computation. The charged particles in a material medium not only respond to the E and B fields but also generate these fields. Complex transport equations must be solved to determine the time and spatial response of charges, for example, the Boltzmann equation or the Fokker–Planck equation or the Navier–Stokes equations. For example, see magnetohydrodynamics, fluid dynamics, electrohydrodynamics, superconductivity, stellar evolution. An entire physical apparatus for dealing with these matters has developed. See for example, Green–Kubo relations and Green's function (many-body theory).

Force on a current-carrying wire

When a wire carrying an electric current is placed in a magnetic field, each of the moving charges, which comprise the current, experiences the Lorentz force, and together they can create a macroscopic force on the wire (sometimes called the Laplace force). By combining the Lorentz force law above with the definition of electric current, the following equation results, in the case of a straight stationary wire in a homogeneous field: where ℓ is a vector whose magnitude is the length of the wire, and whose direction is along the wire, aligned with the direction of the conventional current I.

If the wire is not straight, the force on it can be computed by applying this formula to each infinitesimal segment of wire , then adding up all these forces by integration. This results in the same formal expression, but ℓ should now be understood as the vector connecting the end points of the curved wire with direction from starting to end point of conventional current. Usually, there will also be a net torque.

If, in addition, the magnetic field is inhomogeneous, the net force on a stationary rigid wire carrying a steady current I is given by integration along the wire,

One application of this is Ampère's force law, which describes how two current-carrying wires can attract or repel each other, since each experiences a Lorentz force from the other's magnetic field.

EMF

The magnetic force (qv × B) component of the Lorentz force is responsible for motional electromotive force (or motional EMF), the phenomenon underlying many electrical generators. When a conductor is moved through a magnetic field, the magnetic field exerts opposite forces on electrons and nuclei in the wire, and this creates the EMF. The term "motional EMF" is applied to this phenomenon, since the EMF is due to the motion of the wire.

In other electrical generators, the magnets move, while the conductors do not. In this case, the EMF is due to the electric force (qE) term in the Lorentz Force equation. The electric field in question is created by the changing magnetic field, resulting in an induced EMF, as described by the Maxwell–Faraday equation (one of the four modern Maxwell's equations).

Both of these EMFs, despite their apparently distinct origins, are described by the same equation, namely, the EMF is the rate of change of magnetic flux through the wire. (This is Faraday's law of induction, see below.) Einstein's special theory of relativity was partially motivated by the desire to better understand this link between the two effects. In fact, the electric and magnetic fields are different facets of the same electromagnetic field, and in moving from one inertial frame to another, the solenoidal vector field portion of the E-field can change in whole or in part to a B-field or vice versa.

Lorentz force and Faraday's law of induction

Given a loop of wire in a magnetic field, Faraday's law of induction states the induced electromotive force (EMF) in the wire is: where is the magnetic flux through the loop, B is the magnetic field, Σ(t) is a surface bounded by the closed contour ∂Σ(t), at time t, dA is an infinitesimal vector area element of Σ(t) (magnitude is the area of an infinitesimal patch of surface, direction is orthogonal to that surface patch).

The sign of the EMF is determined by Lenz's law. Note that this is valid for not only a stationary wire – but also for a moving wire.

From Faraday's law of induction (that is valid for a moving wire, for instance in a motor) and the Maxwell Equations, the Lorentz Force can be deduced. The reverse is also true, the Lorentz force and the Maxwell Equations can be used to derive the Faraday Law.

Let Σ(t) be the moving wire, moving together without rotation and with constant velocity v and Σ(t) be the internal surface of the wire. The EMF around the closed path ∂Σ(t) is given by: where is the electric field and dℓ is an infinitesimal vector element of the contour ∂Σ(t).

NB: Both dℓ and dA have a sign ambiguity; to get the correct sign, the right-hand rule is used, as explained in the article Kelvin–Stokes theorem.

The above result can be compared with the version of Faraday's law of induction that appears in the modern Maxwell's equations, called here the Maxwell–Faraday equation:

The Maxwell–Faraday equation also can be written in an integral form using the Kelvin–Stokes theorem.

So we have, the Maxwell Faraday equation: and the Faraday Law,

The two are equivalent if the wire is not moving. Using the Leibniz integral rule and that div B = 0, results in, and using the Maxwell Faraday equation, since this is valid for any wire position it implies that,

Faraday's law of induction holds whether the loop of wire is rigid and stationary, or in motion or in process of deformation, and it holds whether the magnetic field is constant in time or changing. However, there are cases where Faraday's law is either inadequate or difficult to use, and application of the underlying Lorentz force law is necessary. See inapplicability of Faraday's law.

If the magnetic field is fixed in time and the conducting loop moves through the field, the magnetic flux ΦB linking the loop can change in several ways. For example, if the B-field varies with position, and the loop moves to a location with different B-field, ΦB will change. Alternatively, if the loop changes orientation with respect to the B-field, the B ⋅ dA differential element will change because of the different angle between B and dA, also changing ΦB. As a third example, if a portion of the circuit is swept through a uniform, time-independent B-field, and another portion of the circuit is held stationary, the flux linking the entire closed circuit can change due to the shift in relative position of the circuit's component parts with time (surface ∂Σ(t) time-dependent). In all three cases, Faraday's law of induction then predicts the EMF generated by the change in ΦB.

Note that the Maxwell Faraday's equation implies that the Electric Field E is non conservative when the Magnetic Field B varies in time, and is not expressible as the gradient of a scalar field, and not subject to the gradient theorem since its curl is not zero.

Lorentz force in terms of potentials

See also: Mathematical descriptions of the electromagnetic field, Maxwell's equations, and Helmholtz decompositionThe E and B fields can be replaced by the magnetic vector potential A and (scalar) electrostatic potential ϕ by where ∇ is the gradient, ∇⋅ is the divergence, and ∇× is the curl.

The force becomes

Using an identity for the triple product this can be rewritten as,

(Notice that the coordinates and the velocity components should be treated as independent variables, so the del operator acts only on , not on ; thus, there is no need of using Feynman's subscript notation in the equation above). Using the chain rule, the total derivative of is: so that the above expression becomes:

With v = ẋ, we can put the equation into the convenient Euler–Lagrange form

where and

Lorentz force and analytical mechanics

See also: MomentumThe Lagrangian for a charged particle of mass m and charge q in an electromagnetic field equivalently describes the dynamics of the particle in terms of its energy, rather than the force exerted on it. The classical expression is given by: where A and ϕ are the potential fields as above. The quantity can be thought as a velocity-dependent potential function. Using Lagrange's equations, the equation for the Lorentz force given above can be obtained again.

Derivation of Lorentz force from classical Lagrangian (SI units)For an A field, a particle moving with velocity v = ṙ has potential momentum , so its potential energy is . For a ϕ field, the particle's potential energy is .

The total potential energy is then: and the kinetic energy is: hence the Lagrangian:

Lagrange's equations are (same for y and z). So calculating the partial derivatives: equating and simplifying: and similarly for the y and z directions. Hence the force equation is:

The potential energy depends on the velocity of the particle, so the force is velocity dependent, so it is not conservative.

The relativistic Lagrangian is

The action is the relativistic arclength of the path of the particle in spacetime, minus the potential energy contribution, plus an extra contribution which quantum mechanically is an extra phase a charged particle gets when it is moving along a vector potential.

Derivation of Lorentz force from relativistic Lagrangian (SI units)The equations of motion derived by extremizing the action (see matrix calculus for the notation): are the same as Hamilton's equations of motion: both are equivalent to the noncanonical form: This formula is the Lorentz force, representing the rate at which the EM field adds relativistic momentum to the particle.

Relativistic form of the Lorentz force

Covariant form of the Lorentz force

Field tensor

Main articles: Covariant formulation of classical electromagnetism and Mathematical descriptions of the electromagnetic fieldUsing the metric signature (1, −1, −1, −1), the Lorentz force for a charge q can be written in covariant form:

where p is the four-momentum, defined as τ the proper time of the particle, F the contravariant electromagnetic tensor and U is the covariant 4-velocity of the particle, defined as: in which is the Lorentz factor.

The fields are transformed to a frame moving with constant relative velocity by: where Λα is the Lorentz transformation tensor.

Translation to vector notation

The α = 1 component (x-component) of the force is

Substituting the components of the covariant electromagnetic tensor F yields

Using the components of covariant four-velocity yields

The calculation for α = 2, 3 (force components in the y and z directions) yields similar results, so collecting the 3 equations into one: and since differentials in coordinate time dt and proper time dτ are related by the Lorentz factor, so we arrive at

This is precisely the Lorentz force law, however, it is important to note that p is the relativistic expression,

Lorentz force in spacetime algebra (STA)

The electric and magnetic fields are dependent on the velocity of an observer, so the relativistic form of the Lorentz force law can best be exhibited starting from a coordinate-independent expression for the electromagnetic and magnetic fields , and an arbitrary time-direction, . This can be settled through spacetime algebra (or the geometric algebra of spacetime), a type of Clifford algebra defined on a pseudo-Euclidean space, as and is a spacetime bivector (an oriented plane segment, just like a vector is an oriented line segment), which has six degrees of freedom corresponding to boosts (rotations in spacetime planes) and rotations (rotations in space-space planes). The dot product with the vector pulls a vector (in the space algebra) from the translational part, while the wedge-product creates a trivector (in the space algebra) who is dual to a vector which is the usual magnetic field vector. The relativistic velocity is given by the (time-like) changes in a time-position vector , where (which shows our choice for the metric) and the velocity is

The proper (invariant is an inadequate term because no transformation has been defined) form of the Lorentz force law is simply

Note that the order is important because between a bivector and a vector the dot product is anti-symmetric. Upon a spacetime split like one can obtain the velocity, and fields as above yielding the usual expression.

Lorentz force in general relativity

In the general theory of relativity the equation of motion for a particle with mass and charge , moving in a space with metric tensor and electromagnetic field , is given as where ( is taken along the trajectory), , and .

The equation can also be written as where is the Christoffel symbol (of the torsion-free metric connection in general relativity), or as where is the covariant differential in general relativity (metric, torsion-free).

Applications

The Lorentz force occurs in many devices, including:

- Cyclotrons and other circular path particle accelerators

- Mass spectrometers

- Velocity Filters

- Magnetrons

- Lorentz force velocimetry

In its manifestation as the Laplace force on an electric current in a conductor, this force occurs in many devices including:

- Electric motors

- Railguns

- Linear motors

- Loudspeakers

- Magnetoplasmadynamic thrusters

- Electrical generators

- Homopolar generators

- Linear alternators

See also

- Hall effect

- Electromagnetism

- Gravitomagnetism

- Ampère's force law

- Hendrik Lorentz

- Maxwell's equations

- Formulation of Maxwell's equations in special relativity

- Moving magnet and conductor problem

- Abraham–Lorentz force

- Larmor formula

- Cyclotron radiation

- Magnetoresistance

- Scalar potential

- Helmholtz decomposition

- Guiding center

- Field line

- Coulomb's law

- Electromagnetic buoyancy

Footnotes

- ^ In SI units, B is measured in teslas (symbol: T). In Gaussian-cgs units, B is measured in gauss (symbol: G). See e.g. "Geomagnetism Frequently Asked Questions". National Geophysical Data Center. Retrieved 21 October 2013.)

- H is measured in amperes per metre (A/m) in SI units, and in oersteds (Oe) in cgs units. "International system of units (SI)". NIST reference on constants, units, and uncertainty. National Institute of Standards and Technology. 12 April 2010. Retrieved 9 May 2012.

- Huray, Paul G. (2009-11-16). Maxwell's Equations. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-54276-7.

- ^ Huray, Paul G. (2010). Maxwell's Equations. Wiley-IEEE. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-470-54276-7.

- ^ Dahl, Per F. (1997). Flash of the Cathode Rays: A History of J J Thomson's Electron. CRC Press. p. 10.

- ^ Paul J. Nahin, Oliver Heaviside, JHU Press, 2002.

- See, for example, Jackson, pp. 777–8.

- J.A. Wheeler; C. Misner; K.S. Thorne (1973). Gravitation. W.H. Freeman & Co. pp. 72–73. ISBN 0-7167-0344-0.. These authors use the Lorentz force in tensor form as definer of the electromagnetic tensor F, in turn the fields E and B.

- I.S. Grant; W.R. Phillips; Manchester Physics (1990). Electromagnetism (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. p. 122. ISBN 978-0-471-92712-9.

- I.S. Grant; W.R. Phillips; Manchester Physics (1990). Electromagnetism (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. p. 123. ISBN 978-0-471-92712-9.

- Gauss, Carl Friedrich (1867). Carl Friedrich Gauss Werke. Fünfter Band. Königliche Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften zu Göttingen. p. 617.

- ^ See Jackson, page 2. The book lists the four modern Maxwell's equations, and then states, "Also essential for consideration of charged particle motion is the Lorentz force equation, F = q(E + v × B), which gives the force acting on a point charge q in the presence of electromagnetic fields."

- See Griffiths, page 204.

- For example, see the website of the Lorentz Institute or Griffiths.

- ^ Griffiths, David J. (1999). Introduction to electrodynamics. reprint. with corr. (3rd ed.). Upper Saddle River, New Jersey : Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-805326-0.

- Delon, Michel (2001). Encyclopedia of the Enlightenment. Chicago, IL: Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers. p. 538. ISBN 157958246X.

- Goodwin, Elliot H. (1965). The New Cambridge Modern History Volume 8: The American and French Revolutions, 1763–93. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 130. ISBN 9780521045469.

- Meyer, Herbert W. (1972). A History of Electricity and Magnetism. Norwalk, Connecticut: Burndy Library. pp. 30–31. ISBN 0-262-13070-X.

- Verschuur, Gerrit L. (1993). Hidden Attraction : The History And Mystery Of Magnetism. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 78–79. ISBN 0-19-506488-7.

- Darrigol, Olivier (2000). Electrodynamics from Ampère to Einstein. Oxford, : Oxford University Press. pp. 9, 25. ISBN 0-19-850593-0.

- Verschuur, Gerrit L. (1993). Hidden Attraction : The History And Mystery Of Magnetism. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 76. ISBN 0-19-506488-7.

- Darrigol, Olivier (2000). Electrodynamics from Ampère to Einstein. Oxford, : Oxford University Press. pp. 126–131, 139–144. ISBN 0-19-850593-0.

- M.A, J. J. Thomson (1881-04-01). "XXXIII. On the electric and magnetic effects produced by the motion of electrified bodies". The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science. 11 (68): 229–249. doi:10.1080/14786448108627008. ISSN 1941-5982.

- Darrigol, Olivier (2000). Electrodynamics from Ampère to Einstein. Oxford, : Oxford University Press. pp. 200, 429–430. ISBN 0-19-850593-0.

- Heaviside, Oliver (April 1889). "On the Electromagnetic Effects due to the Motion of Electrification through a Dielectric". Philosophical Magazine. 27: 324.

- Lorentz, Hendrik Antoon, Versuch einer Theorie der electrischen und optischen Erscheinungen in bewegten Körpern, 1895.

- Darrigol, Olivier (2000). Electrodynamics from Ampère to Einstein. Oxford, : Oxford University Press. p. 327. ISBN 0-19-850593-0.

- Whittaker, E. T. (1910). A History of the Theories of Aether and Electricity: From the Age of Descartes to the Close of the Nineteenth Century. Longmans, Green and Co. pp. 420–423. ISBN 1-143-01208-9.

- See Griffiths, page 326, which states that Maxwell's equations, "together with the force law...summarize the entire theoretical content of classical electrodynamics".

- "Physics Experiments". www.physicsexperiment.co.uk. Archived from the original on 2018-07-08. Retrieved 2018-08-14.

- ^ See Griffiths, pages 301–3.

- Tai L. Chow (2006). Electromagnetic theory. Sudbury MA: Jones and Bartlett. p. 395. ISBN 0-7637-3827-1.

- ^ Landau, L. D.; Lifshitz, E. M.; Pitaevskiĭ, L. P. (1984). Electrodynamics of continuous media; Volume 8 Course of Theoretical Physics (Second ed.). Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann. p. §63 (§49 pp. 205–207 in 1960 edition). ISBN 0-7506-2634-8.

- Roger F. Harrington (2003). Introduction to electromagnetic engineering. Mineola, New York: Dover Publications. p. 56. ISBN 0-486-43241-6.

- M N O Sadiku (2007). Elements of electromagnetics (Fourth ed.). NY/Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 391. ISBN 978-0-19-530048-2.

- Kibble, T.W.B. (1973). Classical Mechanics. European Physics Series (2nd ed.). McGraw Hill. UK. ISBN 0-07-084018-0.

- Lanczos, Cornelius (January 1986). The variational principles of mechanics (Fourth ed.). New York. ISBN 0-486-65067-7. OCLC 12949728.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Jackson, J.D. Chapter 11

- Hestenes, David. "SpaceTime Calculus".

References

The numbered references refer in part to the list immediately below.

- Feynman, Richard Phillips; Leighton, Robert B.; Sands, Matthew L. (2006). The Feynman lectures on physics (3 vol.). Pearson / Addison-Wesley. ISBN 0-8053-9047-2.: volume 2.

- Griffiths, David J. (1999). Introduction to electrodynamics (3rd ed.). Upper Saddle River, : Prentice-Hall. ISBN 0-13-805326-X.

- Jackson, John David (1999). Classical electrodynamics (3rd ed.). New York, : Wiley. ISBN 0-471-30932-X.

- Serway, Raymond A.; Jewett, John W. Jr. (2004). Physics for scientists and engineers, with modern physics. Belmont, : Thomson Brooks/Cole. ISBN 0-534-40846-X.

- Srednicki, Mark A. (2007). Quantum field theory. Cambridge, ; New York : Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-86449-7.

External links

- Lorentz force (demonstration)

- Interactive Java applet on the magnetic deflection of a particle beam in a homogeneous magnetic field Archived 2011-08-13 at the Wayback Machine by Wolfgang Bauer

It says that the electromagnetic force on a charge q is a combination of (1) a force in the direction of the electric field E (proportional to the magnitude of the field and the quantity of charge), and (2) a force at right angles to both the magnetic field B and the velocity v of the charge (proportional to the magnitude of the field, the charge, and the velocity).

It says that the electromagnetic force on a charge q is a combination of (1) a force in the direction of the electric field E (proportional to the magnitude of the field and the quantity of charge), and (2) a force at right angles to both the magnetic field B and the velocity v of the charge (proportional to the magnitude of the field, the charge, and the velocity).

in which r is the position vector of the charged particle, t is time, and the overdot is a time derivative.

in which r is the position vector of the charged particle, t is time, and the overdot is a time derivative.

Notice that the magnetic field does not contribute to the power because the magnetic force is always perpendicular to the velocity of the particle.

Notice that the magnetic field does not contribute to the power because the magnetic force is always perpendicular to the velocity of the particle.

where

where  is the force on a small piece of the charge distribution with charge

is the force on a small piece of the charge distribution with charge  . If both sides of this equation are divided by the volume of this small piece of the charge distribution

. If both sides of this equation are divided by the volume of this small piece of the charge distribution  , the result is:

, the result is:

where

where  is the force density (force per unit volume) and

is the force density (force per unit volume) and  is the

is the  so the continuous analogue to the equation is

so the continuous analogue to the equation is

, using

, using  , in turn this can be combined with the

, in turn this can be combined with the  to obtain the

to obtain the  where

where  is the

is the

is the density of free charge;

is the density of free charge;  is the

is the  is the density of free current; and

is the density of free current; and  is the

is the

where c is the

where c is the  where ε0 is the

where ε0 is the  Thomson derived the correct basic form of the formula, but, because of some miscalculations and an incomplete description of the

Thomson derived the correct basic form of the formula, but, because of some miscalculations and an incomplete description of the  where ℓ is a vector whose magnitude is the length of the wire, and whose direction is along the wire, aligned with the direction of the

where ℓ is a vector whose magnitude is the length of the wire, and whose direction is along the wire, aligned with the direction of the  , then adding up all these forces by

, then adding up all these forces by

where

where

is the

is the  where

where  is the electric field and dℓ is an

is the electric field and dℓ is an

and the Faraday Law,

and the Faraday Law,

and using the Maxwell Faraday equation,

and using the Maxwell Faraday equation,

since this is valid for any wire position it implies that,

since this is valid for any wire position it implies that,

where ∇ is the gradient, ∇⋅ is the divergence, and ∇× is the

where ∇ is the gradient, ∇⋅ is the divergence, and ∇× is the

, not on

, not on  ; thus, there is no need of using

; thus, there is no need of using  so that the above expression becomes:

so that the above expression becomes:

and

and

where A and ϕ are the potential fields as above. The quantity

where A and ϕ are the potential fields as above. The quantity  can be thought as a velocity-dependent potential function. Using

can be thought as a velocity-dependent potential function. Using  , so its potential energy is

, so its potential energy is  . For a ϕ field, the particle's potential energy is

. For a ϕ field, the particle's potential energy is  .

.

and the

and the  hence the Lagrangian:

hence the Lagrangian:

(same for y and z). So calculating the partial derivatives:

(same for y and z). So calculating the partial derivatives:

equating and simplifying:

equating and simplifying:

and similarly for the y and z directions. Hence the force equation is:

and similarly for the y and z directions. Hence the force equation is:

are the same as

are the same as

both are equivalent to the noncanonical form:

both are equivalent to the noncanonical form:

This formula is the Lorentz force, representing the rate at which the EM field adds relativistic momentum to the particle.

This formula is the Lorentz force, representing the rate at which the EM field adds relativistic momentum to the particle.

τ the

τ the  and U is the covariant

and U is the covariant  in which

in which

is the

is the  where Λα is the

where Λα is the

and since differentials in coordinate time dt and proper time dτ are related by the Lorentz factor,

and since differentials in coordinate time dt and proper time dτ are related by the Lorentz factor,

so we arrive at

so we arrive at

, and an arbitrary time-direction,

, and an arbitrary time-direction,  . This can be settled through

. This can be settled through  and

and

, where

, where

(which shows our choice for the metric) and the velocity is

(which shows our choice for the metric) and the velocity is

and charge

and charge  , moving in a space with metric tensor

, moving in a space with metric tensor  and electromagnetic field

and electromagnetic field  , is given as

, is given as

where

where  (

( is taken along the trajectory),

is taken along the trajectory),  , and

, and  .

.

where

where  is the

is the  where

where  is the

is the