| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Firefighter's helmet" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (April 2013) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

For centuries, firefighters have worn helmets to protect them from heat, cinders and falling objects. Although the shape of most fire helmets has changed little over the years, their composition has evolved from traditional leather to metals (including brass, nickel and aluminum), to composite helmets constructed of lightweight polymers and other plastics.

Leather helmets

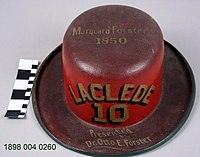

The original American fire helmet was created by a New York City luggage maker who was also a volunteer fireman in the 1830s, seeking a better design more tailored to the unique requirements for firefighting than the "stovepipe" helmets then in use. Stovepipe was essentially a top hat made of stiff leather with painted design to identify fire company and provided no protection. Leather was chosen as the preferred material both because it was what the man, Henry Gratacap, was familiar with, but also because thick treated leather was flame-resistant and highly resistant to breaking apart. Leatherhead is a term for evolutions of these leather helmets still used by many firefighters in North America. Leatherhead is also slang for a firefighter who uses a leather helmet as opposed to more modern composite helmets. The leather helmet is an international symbol of firefighters dating to the early years of organized civilian firefighting.

Typically, traditional leather helmets have a brass eagle adornment affixed to the helmet's top front of the helmet to secure a leather shield to the helmet front, though on the original design it also served as a glass-breaking device. Leather helmet usage continues to increase in popularity across the US fire service with a cultural embrace of American tradition with the balance of safety in mind as compared to many current plastic-based alternative helmets. Canadian fire departments (e.g. Toronto Fire Services) that use the Leatherhead have a beaver in place of the eagle for the brass adornment. Such leather helmets, as well as modern derivatives that retain the classic shape but use lighter, more modern composite materials, remain very popular in North America and around the world in places that derive their firefighting traditions from North America.

Brass eagle and beaver

The eagle's origins can be traced to approximately 1825. An unknown sculptor created a commemorative figure for a volunteer firefighter's grave. Firefighters did not wear eagles before that, but eagles became associated with fire helmets ever since. Canadian firefighters adorn their helmets with the beaver because it is Canada's national animal.

These ornaments protrude from the helmet and can catch on window sashes, wires and other obstacles, frequently leading to damage. As a result, many fire departments provide traditional helmets using modern plastic and composite helmets without eagles or beavers, jokingly referred to as salad bowls, turtle shells and slick tops due to their streamlined shape. However, many firefighters and fire departments still retain the leather helmet as a matter of tradition.

Early respirators

Tyndall's hood

In 1871, British physicist John Tyndall wrote about his new invention, a fireman's respirator, featuring a valve chamber and filter tube. This device used cotton saturated with glycerin, lime and charcoal to filter smoke particles and neutralize carbonic acid. The device was featured in the July 1875 issue of Manufacturer and Builder.

Neally's smoke-excluding mask

George Neally patented a smoke-excluding mask in 1877 that he marketed to fire departments. This device featured a face mask with glass eyepieces and rubber tubes, allowing respiration through a filter carried on the chest.

Merriman's smoke mask

A Denver firefighter known as Merriman invented an early hose mask that was featured in the January 7, 1892 issue of Fireman's Herald. This respirator featured a tube like that of an elephant trunk connected to an air hose that ran parallel to the firefighter's water hose.

Loeb respirator

Bernhard Loeb of Berlin patented a respirator (US patent #533854) in 1895 that featured a triple-chambered canister carried on the waist that contained liquid chemicals, granulated charcoal and wadding. This respirator was used by the Brooklyn Fire Department.

Dräger smoke helmet

Invented in 1903 by Dräger & Gerling of Lübeck, Germany, the smoke helmet was a fully enclosed metal helmet with glass face mask, featuring two breathing bags covered by a leather flap worn over the chest. This respirator became so critical to mine rescue operations that rescue workers became known as draegermen.

Metal helmets

Napoleonic helmets

Napoleon Bonaparte reordered the various fire fighting organisations in Paris (and later other cities) into a unit of the French Army called the Sapeurs-pompiers. They wore a brass helmet with a high central crest, similar to that worn by dragoon cavalry, with a frontal plate on which a badge representing their city was embossed. This style of helmet was widely copied across Europe and beyond.

Merryweather helmet

Merryweather helmets were used by British fire brigades from the Victorian era until well into the 20th century. These helmets were modelled on the helmets of the Sapeurs-pompiers which Captain Sir Eyre Massey Shaw had seen on a visit to Paris and introduced to the Metropolitan Fire Brigade in London in 1868, replacing a black leather helmet. The design was widely copied by other British and British Empire fire services. These helmets were made of brass, but those belonging to officers were silver plated. Metal helmets are conductive, a safety hazard as use of electricity became widespread, so a new helmet made from a composite of cork and rubber was introduced in London and elsewhere from 1936. However, during World War II, military-style steel helmets were adopted, similar to the Brodie helmet used by the British Army, to improve protection during air raids. A composite helmet was reintroduced after the end of the war. Traditional brass helmets remained in service in Queensland, Australia until 1970.

Aluminium helmets

Some departments, such as the Buffalo Fire Department for example, used aluminium helmets up to the mid-1980s.

German DIN fire helmet

In Germany, many fire brigades still use the old German DIN fire helmet. Early on, this helmet was simply an aluminium alloy version of the M1942 Stahlhelm used by the Wehrmacht, standardized in 1956 and normed in 1964 by DIN 14940. The material was AL-CU-MG, normed by DIN 1725. At about 800 g, it was lighter than most fire fighting helmets.

The color was Wehrmacht black in the beginning or red in Bavaria. The norming process of the 1960s changed color to a fluorescent lime yellow. This helmet uses a white reflecting stripe and black leather neck protection. Most fire brigades use this helmet with an easily mountable visor.

The German DIN fire helmet does not correspond to the currently valid European EN 443 standard for fire helmets due to its conductivity. German fire brigades are allowed to use existing aluminum DIN fire helmets, but if new helmets are necessary, firefighters must purchase either composite or a newly developed version of the old helmet with EN 443-compatible coating. At about 900 g, coated aluminum helmets are still relatively lightweight. Some manufacturers currently produce fire helmets constructed of glass fibre reinforced plastic, replicating the look of old German DIN fire helmets. However, it is not uncommon that fire brigades move to modern helmets like the F1.

-

An early 19th century French fire commander's helmet, on display in Basel

-

A Victorian Scottish fireman's helmet, exhibited at Huntly House Museum

A Victorian Scottish fireman's helmet, exhibited at Huntly House Museum

-

A Russian fire helmet dating from before the Russian Revolution in 1917

A Russian fire helmet dating from before the Russian Revolution in 1917

-

London firemen wearing Brodie-like steel helmets during World War II

London firemen wearing Brodie-like steel helmets during World War II

-

Historic German fire helmets, predecessors of the DIN helmet

Historic German fire helmets, predecessors of the DIN helmet

-

German firefighters with DIN helmets

German firefighters with DIN helmets

Modern composite helmets

Modern structural helmet

Modern structural helmets (that is, those intended for structure fires) are made of thermoplastic or composite materials. Such helmets were designed to provide a more modern, sleeker look, and lighter weight compared to the traditional American helmet design, while retaining the distinctive profile. If desired, a face shield can be attached to the front. The Newer "Metro" helmets (the name given by several leading helmet manufacturers) with smaller brims and rounded edges are also much lighter than both leather and composite traditional helmets. However, designs which emulate the original New York-style American helmet design persist due to their continuing effectiveness and a general preference towards tradition or traditional appearance, and remain widely popular in both leather and composite. North American manufacturers continue to make both styles in parallel. The New York and Metro style helmets are worn in the United States and Canada. The Metro style is also used in Australia and parts of Asia (notably Macau, Taiwan, and Guangzhou) however, they do not feature the shield at the front, and instead will often display the crest or logo of the local fire authority. Most countries outside of the continental US, especially Europe, use a different style of fire helmet which covers more of the head, including the ears, and will sometimes have a nape protector at the back. This style is often referred to as a "Euro" style helmet, and most are fitted with a full face visor, eye protection, and a light. Recent examples of a "Euro" style helmet include the MSA Gallet F1 XF [fr], and the Rosenbauer HEROS-Titan Pro.

Urban rescue helmet

These helmets are used for urban search and rescue, technical rescue, and medical rescue applications and are shaped differently from traditional fire helmets. Most designs are derived from them, but feature a lower profile and elimination of excess protective area to facilitate better freedom of movement for the head in confined spaces. Those derived from North American-style helmets often appear to be similar to a commercial hard hat, while those derived from European styles such as the MSA Gallet F2 appear more similar to rock climbing helmets. As they are made from the same materials, these types of helmet often carry the same flame, impact and heat resistance standards that their larger counterparts do, and still offer mostly seamless compatibility with SCBAs.

Helmet colors

In some countries, most notably the United States and other Anglophone countries, the firefighter's helmet color often denotes the wearer's rank or position. In Britain, most firefighters wear yellow helmets; watch managers (two grades above a regular firefighter) and above wear white helmets. Rank is further indicated by black stripes around the helmets. In Canada, regular firefighters wear yellow or black; captains (two grades above regular) are in red and senior command officers in white. Likewise in the United States, red helmets denote company officers (one or two grades above regular), while white helmets denote chief officers (three or more grades above regular).

However the specific meaning of a helmet's color or style varies from region to region and department to department. One noteworthy example is the Los Angeles County Fire Department's use of MSA Safety "Topgard" Helmets depicted in the 1970s television series Emergency!. Firefighters used all black with colored company numbers on the shield below the "L.A. County" in blue on the top half. Engine and squad companies used white numbers, with paramedics switching to green and a two-color "paramedic" decal later affixed to either side of the helmet. Truck companies used red numbers. Captains' helmets were black with a white stripe down the helmet's center ridge, and the numeric shield portion in white. Battalion Chiefs helmets were solid white with black numbers. These helmets have since been discontinued in favor of a more modern style using bright yellow, orange, and red, among other colors to denote rank, though the colored number panels persist. This particular setup has been copied by a number of other California fire services. Another example is the San Francisco Fire Department. Engine company helmets are typically all black; truck company helmets are black with alternating red and white quarters on the helmet dome. Most other fire services in the United States and Canada simply use either black or yellow for most firefighters and white for commanders, with some using red for denoting unit leaders.

The South Australian Country Fire Service, as with many Australian fire services, use specific colors for specific roles. White helmets are for firefighters (with a red stripe for senior firefighters). Lieutenants have yellow helmets; captains have yellow with a red stripe, deputy group officers and above have red helmets while paid staff have a blue stripe on their helmet.

In New Zealand, helmet colours were changed in 2013 to assist with identification of the command structure at a large multi-agency incident. Firefighters wear yellow helmets, plain for a base-rank firefighter, with one red stripe for a qualified firefighter, and with two red stripes for a senior firefighter. Station officers wear red helmets with one blue stripe (previously yellow with one blue stripe), while senior station officers wear red helmets with two blue stripes (previously yellow with two blue stripes). Chief fire officers and their deputies wear white helmets; regional and area commanders and their assistants wear silver helmets; and the national commander and their deputies wear black helmets. Trainee and recruit firefighters wear fluro-green helmets (previously red).

In Germany and Austria lime-yellow phosphorescent helmets are commonly used. Different colours, which indicate different ranks, are rarely used. However, it is common to use different kind of identification markings on the helmets. As fire service is mainly organized by the different federal states and in the end is the responsibility of the different communities, there is no standard kind of identification markings for helmets. In Bavaria for example the "Kommandant" (elected fire chief) is marked with a red vertical stripe on the helmet and the “Gruppenführer” (group leaders) with thin black rubber bands around the helmets. It is also quite common to use helmet markings for different possible functions like medic or SCBA. While identification markings according to the rank on the helmet are permanent, officers and sub-officers usually wear coloured vests over their bunker-gear in order to indicate their currently carried leading-position.

In Poland it is legally regulated by the National Headquarters of the State Fire Service that paid full-time firefighters from the State Fire Service use red and volunteer firefighters from Volunteer Fire Services use white as the colour of their helmets. However it is common to see Volunteer Services to use different colors such as yellow or somethimes silver, while the State Service sticks to the rule.

Fire Helmet Safety Standards

Many countries, regions and industry groups have developed safety standards that outline performance criteria as well as information on the selection, care, and maintenance of fire helmets

North America

In North America, the National Fire Protection Agency has developed several industry consensus standards for various types of helmets that may be used by fire service personnel, including:

- NFPA 1971, Standard on Protective Ensembles for Structural Fire Fighting and Proximity Fire Fighting

- NFPA 1951, Standard on Protective Ensembles for Technical Rescue Incidents

- NFPA 1952, Standard on Surface Water Operations Protective Clothing and Equipment

- NFPA 1977, Standard on Protective Clothing and Equipment for Wildland Fire Fighting and Urban Interface Fire Fighting

In order to comply with the NFPA standards, helmets are required to be tested and certified by independent third-parties, and bear the certifying body's logo and a compliance statement. Such third-party certifications are issued by the Safety Equipment Institute (SEI) and UL Solutions.

Europe

European Standards developed for the performance of helmets that may be used by fire service personnel include:

- EN 443, Helmets for fire fighting in buildings and other structures

- EN 16471, Firefighters helmets - Helmets for wildland fire fighting

- EN 16473, Firefighters helmets - Helmets for technical rescue

See also

- Fire safety

- Glossary of firefighting equipment

- Glossary of firefighting terms

- L'art pompier

- List of headgear

- Cap

References

- "Fire Helmets".

- "History of the Leather Helmet". Oceancityfools.com. Archived from the original on 2013-06-21. Retrieved 2014-06-03.

- Gibson, Ella (November 19, 2014). "Episode 35 Leather Fire Helmet". A History of Central Florida Podcast. Retrieved February 7, 2016.

- ^ Taggart, Ian. "The Invention of the Gas Mask". Archived from the original on 2013-05-02. Retrieved 2013-04-23.

- "draegerman". Merriam-Webster. Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 2013-04-23.

- Haythornthwaite, Philip (1988), Napoleon's Specialist Troops Osprey Books, ISBN 9781780969794 (p. 19)

- Blackstone, Geoffrey Vaughan (1957), A History of the British Fire Service, Routledge (p. 178)

- Turnham, Andy. "Hot Lids - The London Fire Brigade". www.spanglefish.com/hot-lids. Retrieved 18 February 2016.

- Bowden, Bradley (2008), Against All Odds: The History of the United Firefighters Union in Queensland: 1917-2008, Federation Press, ISBN 978-186287-693-4 (p. 6)

- "Rescue helmet, SAR - Areo-Feu". www.areo-feu.com. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved 19 April 2018.

- "Rank insignia". New Zealand Fire Service. Archived from the original on January 10, 2015. Retrieved 2 October 2016.

- http://www.feuerwehr-huerth.de/index.php/technik/helmfarben

- Staatliche Feuerwehrschule Würzburg. "Merkblatt: Kennzeichnung der Dienstkleidungsträger der Feuerwehren in Bayern", pp. 16/17, "http://www.sfs-w.de", 7th modified edition, Status 11/2009.

- Bickert, Leo (6 June 2016). "Helmkennzeichnungen". Alle Feuerwehren in Nordrhein-Westfalen. Leo Bickert. Archived from the original on October 20, 2014. Retrieved 6 September 2016.

- strazacki.pl/ŁS. "Jaki kolor hełmów w OSP? Odpowiadamy". strazacki.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 2022-08-13.

- "Kolory hełmów w straży pożarnej. Czy mają jeszcze znaczenie?". osp.pl. Retrieved 2022-08-13.

- NFPA 1971 Standard on Protective Ensembles for Structural Fire Fighting and Proximity Fire Fighting (2018 ed.). Quincy, MA: National Fire Protection Association. August 21, 2017. p. 18. ISBN 978-145591728-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - NFPA 1951 Standard on Protective Ensembles for Technical Rescue Incidents (2020 ed.). Quincy, MA: National Fire Protection Association. November 24, 2019. p. 14. ISBN 978-145592564-3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - NFPA 1952 Standard on Surface Water Operations Protective Clothing and Equipment (2021 ed.). Quincy, MA: National Fire Protection Association. April 4, 2020. p. 14. ISBN 978-145592652-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - NFPA 1977 Standard on Protective Clothing and Equipment for Wildland Fire Fighting and Urban Interface Fire Fighting (2022 ed.). Quincy, MA: National Fire Protection Association. April 8, 2021. p. 14. ISBN 978-145592808-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link)

External links

- National Emergency Services Museum

- San Francisco Fire Museum page with pictures

- gallet.fr F1 helmet Manufacturer's web site

- Killorglin Fire & Rescue Killorglin Fire & Rescue site includes a breakdown of the parts of the Gallet helmet

- Der Feuerwehrhelm A helmet collection: See fire helmets of the past and the future, from Germany and the whole world.

- Firehelmetcollection A worldwide fire helmets collection from Italy.

- http://home.bt.com/techgadgets/technews/firemans-helmet-can-see-through-smoke-11363895600280?s_intcid=con_RL_Helmet

- Leather Fire Helmet at A History of Central Florida Podcast

| Helmets | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual historical helmets |

| ||||||||||||||

| Combat |

| ||||||||||||||

| Athletic | |||||||||||||||

| Work | |||||||||||||||

| Other | |||||||||||||||