| Part of a series on |

| Chinese legalism |

|---|

|

| Figures |

| Han figures |

| Later figures |

| Relevant texts |

| Relevant articles |

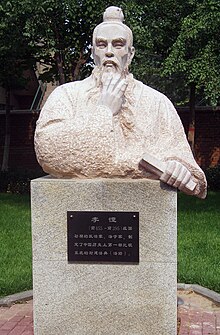

Li Kui (Chinese: 李悝; pinyin: Lǐ Kuī; Wade–Giles: Li K'uei, 455–395 BC) was a Chinese hydraulic engineer, philosopher, and politician. He served as government minister and court advisor to Marquis Wen (r. 403–387 BC) in the state of Wei. In 407 BC, he wrote the Book of Law (Fajing, 法经). Said to have been a main influence on Shang Yang, it served the basis for the codified laws of the Qin and Han dynasties.

His political agendas, as well as the Book of Law, had a deep influence on later thinkers such as Han Feizi and Shang Yang, who would later develop the philosophy of Legalism based on Li Kui's reforms.

Life and reforms

Li Kui was in the service of the Marquis Wen of Wei even before the state of Wei was officially recognized, though little else is known of his early life. He was appointed as Chancellor of the Wei-controlled lands in 422 BC, in order to begin administrative and political reforms; Wei would therefore be the first of the Seven Warring States to embark on the creation of a bureaucratic, rather than a noble-dominated, form of government.

The main agendas of Li Kui's reforms included:

- The institution of meritocracy, rather than inheritance, as the key principle for the selection of officials. By doing this, Li Kui undermined the nobility while enhancing the effectiveness of government. He was responsible for recommending Ximen Bao to oversee Wei's water conservancy projects in the vicinity of Ye, and recommending Wu Qi as a military commander when Wu Qi sought asylum in Wei.

- Giving the state an active role in encouraging agriculture, by 'maximising instruction and agricultural productivity' (盡地力之教). While the precise contents of this reform are unclear, they could have included the spreading of information about agricultural practices, thus encouraging more productive methods of farming.

- Instituting the 'Law of Equalising Purchases' (平籴法), wherein the state purchased grain to fill its granaries in years of good harvest, to ease price fluctuations and serve as a guarantee against famine.

- Codifying the laws of the state, thus creating the Book of Law. The text was in turn subdivided, with laws dealing with theft, banditry, procedures of arrest and imprisonment, and miscellaneous criminal activities.

Legacy

The direct result of these pioneering reform measures was the dominance of Wei in the early decades of the Warring States era. Leveraging its improved economy, Wei achieved considerable military successes under Marquis Wen, including victories against the states of Qin between 413 and 409 BC, Qi in 404 BC, and joint expeditions against Chu with Zhao and Han as its allies.

At the same time, the main tenets of Li Kui's reforms - supporting law over ritual, agrarian production, meritocratic and bureaucratic government and an active role of the state in economic and social affairs - proved an inspiration for later generations of reform-minded thinkers. When Shang Yang sought service in Qin, three decades after Li Kui's death, he brought with him a copy of the Book of Law, which was eventually adapted and became the legal code of Qin.

Along with his contemporary Ximen Bao, he was given oversight in construction of canal and irrigation projects in the State of Wei.

See also

Notes

- Edward L Shaughnessy 2023. A Brief History of Ancient China. https://books.google.com/books?id=xFe8EAAAQBAJ&pg=PA203

- Needham, Volume 4, Part 3 261.

References

- Zhang, Guohua, "Li Kui". Encyclopedia of China (Law Edition), 1st ed.

- Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 4, Part 3. Taipei: Caves Books, Ltd.

This biography of a Chinese philosopher is a stub. You can help Misplaced Pages by expanding it. |

- 455 BC births

- 395 BC deaths

- 5th-century BC Chinese philosophers

- 4th-century BC Chinese people

- 4th-century BC Chinese philosophers

- Chinese hydrologists

- Chinese reformers

- Engineers from Shanxi

- Hydraulic engineering

- People from Yuncheng

- Philosophers of law

- Philosophers from Shanxi

- Politicians from Shanxi

- Legalism (Chinese philosophy)

- Writers from Shanxi

- Zhou dynasty essayists

- Zhou dynasty philosophers

- Zhou dynasty government officials

- Chinese philosopher stubs