During the German occupation of Luxembourg in World War II, some Luxembourgers collaborated with the country's Nazi occupiers. The term Gielemännchen ("yellow men") was adopted by many Luxembourgers, initially to refer to German Nazis in general and later extended to Luxembourg collaborators, deriving from the yellow uniforms of the Nazi Party.

Pre-war period

In the inter-war period, Luxembourg saw the emergence of several fascist movements, mirroring developments in the rest of Western Europe. These movements typically shared the following common characteristics: they were nationalist, anti-Semitic, hostile towards both capitalism and communism, and were made up of the lower middle class. In Luxembourg, they included a number of minuscule, unsuccessful movements such as the Faschistische Partei Luxemburg (Fascist Party of Luxembourg) and the Luxemburgische Nationale Arbeiter- und Mittelstandsbewegung (Luxembourgish National Worker and Middle Class Movement), but also two more significant organisations: the Luxembourg National Party (LNP) published the first edition of the National-Echo in 1936. After this high point, though, its history was marked by quarrels and a lack of funds, and a year later it had faded into obscurity, while attempts to revive it during the German occupation failed.

The Luxemburger Volksjugend (LVJ) / Stoßtrupp Lützelburg was more successful in gathering a determined core of young people, who followed Nazi ideology and saw Adolf Hitler as their leader.

A less overtly political organisation was the Luxemburger Gesellschaft für deutsche Literatur und Kunst (GEDELIT - "Society for German Literature and Art"), which likewise served as a recruitment source for later collaborators. GEDELIT was founded in 1934 to counter the activities of the highly successful Alliance française. From its inception, GEDELIT was under suspicion of being a tool of Nazi Germany, and an apologist for the latter's actions.

However, the extent of these pre-war organisations' influence on the general population's behaviour in occupied Luxembourg remains unclear, as does the continuity (or lack thereof) between these groups and the Volksdeutsche Bewegung (VdB) or Luxembourg sections of the NSDAP. Among these groups, only the LVJ was politically successful, rebranding as the Volksjugend in 1940 and being incorporated into the Hitlerjugend in 1941. The historian Émile Krier has maintained that the Volksdeutsche Bewegung made use of existing pre-war networks when it was founded: Damian Kratzenberg, for example, was the head of GEDELIT, and became head of the country's section of the VdB. However, the evidence for the grassroots membership of the VdB having been members of previous fascist organisations is inconclusive.

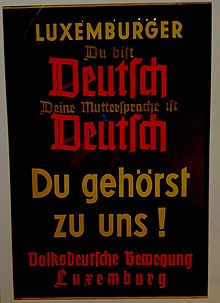

Volksdeutsche Bewegung and NSDAP

Collaborationist movements arose in the first few weeks after the invasion, but received no support from the German military administration, which was in place from May to July 1940. On 19 May, there was a meeting of 28 individuals who had belonged to several of the above-mentioned fascist movements, and who called for Luxembourg to be incorporated into Germany as a Gau. On 13 July, the VdB was officially founded. This included three factions: a group around Damian Kratzenberg, which had been Germanophile before the war and was most active in the cultural sphere; a group that was most interested in cooperating with the occupiers for economic reasons; finally, a third wing around a former journalist, Camille Dennemeyer. This last group was quite young, and exhibited an activism similar to that of the German Sturmabteilung. This wing was seen as harmful to the VdB's public perception, and in November 1940 Dennemeyer and his associates were dismissed from their posts in the movement.

Over the following months, the VdB was massively expanded: the country was divided into 4 districts (Kreise), which were subdivided into local branches (Ortsgruppen), so that by the end of the war there were about 120 local VdB groups. Membership rose until August 1942, when almost a third of the population were members.

The VdB was an ideological defender of Luxembourg's return to the German Empire. On 6 July 1940, when the VdB had not yet officially been founded, it released a public statement, declaring "Luxembourgers, hear the call of blood! It tells you that you are German by race and by language " Its aim was to persuade Luxembourgers to become an indistinguishable part of Nazi Germany. Up until the end of the war, however, the VdB did not formulate a specific ideology, although its public discourse shows the following characteristics: vilification of Jews, condemnations of the Resistance and the grand-ducal family, and a strongly dichotomous argumentation, all of which does not constitute an ideology.

At the same time, the German occupiers were not interested in a self-sufficient collaboration movement. Senior posts in the movement were occupied by Germans, including 3 of 4 district leaders (Kreisleiter). Nevertheless, Nazism had such grave consequences in Luxembourg because there were people at every level of society who were ready to cooperate with the occupier, as illustrated by the 120 Ortsgruppenleiter (local branch leaders). Most of these men were Luxembourgers, and in fact the post was one of the highest that Luxembourgers could attain in the movement. The Ortsgruppenleiter performed continual informer services throughout the war which allowed the German occupiers to keep the country under control for 4 years. The authorities would ask an Ortsgruppenleiter for a political evaluation of an individual at many opportunities, for example when deciding whether to grant someone government benefits, membership in the VdB, access to education, leave for Wehrmacht members, or release from prison or concentration camps. Putting such power in the hands of the Ortsgruppenleiter also allowed them to pursue personal vendettas. These local officials also played a major role in the forced resettlement operations: the commissions in each Kreis that decided individual cases relied on reports from the Ortsgruppenleiter, who in turn used the threat of resettlement as a means of intimidation. Furthermore, they compiled and handed to the occupiers "blacklists" of potential hostages or "donors". After the "Three Acorns," a set of historic fortifications, were painted in the national colours of Luxembourg: red, white and blue, the Ortsgruppenleiter in Clausen presented the authorities with a list of 31 persons who would be able to pay the 100,000 Reichsmark that the occupiers demanded as punishment.

Apart from the VdB, the Nazis tried to cover Luxembourg with a net of political, social and cultural organisations. It became apparent that the VdB, being a mass organisation, was not suitable for forming a collaborationist elite, and so in September 1941 a Luxembourg section of the Nazi party was founded, which had grown to 4,000 members by the end of the war. Other Nazi organisations such as the Hitler Youth, the Bund Deutscher Mädel, the Winterhilfswerk, the NS-Frauenschaft and the Deutsche Arbeitsfront were also introduced in Luxembourg. These organisations subjected the country to a wave of propaganda, which aimed to bring the population "back into the Empire" (Heim ins Reich). This propaganda was not restricted to a few large-scale public events, but attempted to reach the population day in, day out.

Social make-up

Studies have shown that collaboration was a phenomenon in all layers of society. Civil servants, however, were over-represented among the collaborators, and farmers were under-represented, while workers made up the same percentage of collaborators as they did of the general population. If historians today regard the Nazi Party as a "people's party" but with an over-representation of the lower middle class, similarly Luxembourg collaboration found supporters in every part of society, but with some parts being more strongly affected than others.

Some further demographic observations can be made: on average, the collaborators were younger than the general population. Studies show that it was 30- to 40-year-olds who predominated; the Ortsgruppenleiter, however, were significantly younger than the local elites who would usually have filled political roles before the occupation.

In terms of geography, the north and centre of the country were under-represented among collaborators, while the east and south were over-represented. Having had previous contact with Germany was a significant factor for collaborators, as 23% of the Ortsgruppenleiter were either German or of German descent. Several of them had German wives, and those with university degrees had all studied in a German-speaking country. After 1933, Germany appeared to many of these later collaborators as an example to be imitated; when visiting their families or former classmates, they were impressed by the "orderly" appearance that Germany presented.

Military collaboration

With the forced conscription of Luxembourgers into the Wehrmacht from September 1942, the divide between the occupiers and the occupied population increased widened dramatically. However, according to German reports about 1,500 to 2,000 Luxembourgers had volunteered by August 1942 for the German armed forces, including 300 for the Schutzstaffel (SS), and this does not seem to have been pure propaganda.

Economic collaboration

Germany was the most important trading partner of Luxembourg in the interwar period, but the manner in which these trade links developed and changed during the war has not yet been researched. The historian Émile Krier spoke of a process of "rationalisation and concentration" during the war, but this leaves the question as to who the beneficiaries and losers of this process were. Certainly, the Caisse d'Épargne, for example, profited enormously from the elimination of small banks.

According to one historian: "In a sense, one can argue that on 10 May 1940, it was not the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg that the Wehrmacht invaded, but ARBED." From the 1920s, ARBED had grown into a powerful multinational steel producer, which sold its products all over the world. Germany and Luxembourg were highly interdependent when it came to steel production: just before the war, Luxembourg imported 90% of its coke, an essential fuel for the blast furnaces, from Germany; by 1938, Luxembourg was exporting 47.22% of its iron and steel products to Nazi Germany, where these were badly needed due to the Nazis' rearmament programme. Luxembourg's iron ore reserves would make Germany self-sufficient in steel production; in the medium term, the Germans intended to combine the Luxembourg's steel and mining industries with those of Lorraine and the Saar.

From the first months of the occupation, then, the Germans tried hard to bring Luxembourg's steel companies, Hadir, Ougreé-Marihaye and ARBED, under their control. On 2 July 1940 Otto Steinbrinck, the Plenipotentiary for the Iron and Steel Industry in Luxembourg, Belgium and Northern France, called a meeting of the above companies' representatives. Whereas Hadir and Ougrée-Marihaye had their factories confiscated or placed under German supervision, ARBED was the only steel company to maintain its pre-war board of directors, including its managing director, Aloyse Meyer.

Several political and economic actors in the Reich had plans for ARBED, but it was ultimately the Gauleiter who determined its fate. He was intent on keeping the company intact, as it made the otherwise mostly rural Gau Moselland an industrial heavyweight.

In terms of production levels, after the catastrophic results of 1940 due to the invasion and ongoing war, steel production soon resumed but at a reduced rate. Luxembourg's steel factories no longer received a sufficient supply of coke, since the Germans believed it was more efficient to process Swedish ore, which had a higher iron content than that of minette mined in Luxembourg. However, when Nazi Germany moved to a strategy of total war, involving the mobilisation of all resources, the Armaments Minister Albert Speer ensured that from February 1942, Luxembourg's steel factories could work properly. Production increased steadily from mid-1942, and wartime production reached its peak in early 1944, when it also reached pre-war levels.

The production level of Luxembourg's heavy industry was neither held up by passive resistance on the part of the workers, nor obstruction by the management. This shatters Aloyse Meyer's post-war argument when defending himself against accusations of collaboration. Another argument, that Luxembourg managers had no room for manoeuver in the face of the all-powerful occupation authorities, also seems doubtful: Luxembourg managers remained in their posts until the general strike of 1942. The Luxembourg board of directors of ARBED remained in place until March 1942, when it was replaced by a board consisting of three Germans and two Luxembourgers, including Aloyse Meyer.

The latter was never made totally powerless: Like the Gauleiter, Meyer wanted to avoid ARBED being broken up, which made them allies in a sense. It was also the Gauleiter who ensured that Meyer was named head of the Luxembourg section of the Wirtschaftsgruppe Eisen schaffende Industrie, and a member of the board of directors of the Reichsgruppe Eisen, a semi-public body that coordinated steel production from May 1942, and as president of the Gauwirtschaftskammer Moselland (Gau Moselland Chamber of Commerce). Meyer remained ARBED's managing director, and the company continued to produce steel, until the German occupying forces left the country in September 1944. With its factories unscathed and its industrial capacity intact, ARBED was able to show a profit from 1946 again.

The historian Jacques Maas has described ARBED's attitude as one of "survival-collaboration" (collaboration-survie).

The question as to ARBED's willingness to make concessions to the German authorities was already heavily discussed during the post-war trial of Aloyse Meyer, the managing director. The different stances of ARBED and HADIR show that there was certainly some room for maneuver. Unlike the former, the management of HADIR refused to cooperate with the German occupiers. Yet many issues have yet to be examined by historians. It is unclear whether the decline in productivity per worker was due to passive resistance, a lack of raw materials, or a shortage of qualified workers in wartime. Similarly, about 1,000 Ostarbeiter were employed in Luxembourg's iron and steel industry, and their working conditions have yet to be examined. Paul Dostert claims that, in general, industry was able to continue production relatively undisturbed and still made considerable profits under German oversight, but these were disguised by the war-related production stoppages in 1940 and 1944–1945.

End of the war and aftermath

End of the war

In early September 1944, about 10,000 people left Luxembourg with the German civil administration: it is generally assumed that this consisted of 3,500 collaborators and their families. These people were distributed to the German districts (Kreise) of Mayen, Kreuznach, Bernkastel, and St Goar, and tensions soon developed between the refugees from Luxembourg and the German population, whose living conditions were precarious at this point. Furthermore, the fleeing Luxembourg collaborators still remained convinced of a German victory, to the extent that a secret police report mentioned that if the native (German) population heard the "Heil Hitler" greeting, they assumed there were Luxembourgers around.

Retribution

The main resistance groups had formed the umbrella group Unio'n in March, and they tried to establish a level of order after the German withdrawal but before the return of Luxembourg's government-in-exile: in this, they had the support of the American army. Without a legal footing, they arrested numerous collaborators. While this may in fact have prevented the deadly vigilante justice that occurred in other countries, the population's anger did also manifest itself in violent attacks on the arrested collaborators.

In 1945, 5,101 Luxembourgers, including 2,857 men and 2,244 women were in prison for political activities, constituting 1.79% of the population. 12 collaborators were sentenced to death and were shot in Reckenthal in Luxembourg City. 249 were sentenced to forced labour, 1366 were sentenced to prison and 645 were sent to workhouses. Approximately 0.8% of the population were legally punished, then. This included one former minister, the 1925–1926 prime minister Pierre Prüm, who was sentenced in 1946 to four years' imprisonment. At least one mayor was also deposed for political activities by grand-ducal decree on 4 April 1945.

Luxembourg's penal system was ill-prepared to take in such a large number of prisoners. In addition to the prison in Grund, there were about 20 other facilities, some of which had been built by the Germans during the war. Many of these were overcrowded, and had poor standards of hygiene.

Apart from their political activities, collaborators also had to account for their actions against Jews, denouncing forced conscripts in hiding, and spying on Luxembourg's population.

Collaborators after the war

The conditions of collaborators and their families after the war were difficult. If a collaborator was imprisoned, the family would find themselves without an income, and in some cases their property might be confiscated. Often, the wife would take the children, leave the village and move back to her parents. There were still acts of violence against the families of collaborators as late as 1947.

At the same time, this social exclusion of the collaborators meant that old ties from the war lived on and remained strong. In one case, a grocer who had been convicted after the war mostly had former collaborators among his customers. Similarly, some business owners preferentially employed former collaborators.

There were some failed attempts in the 1950s and 1970s to politically organise the former collaborators. The same people are not known to have had any involvement in the resurgence of populist right-wing groups in the 1980s and 1990s.

Public memory and historiography

For several years after the war, there was a taboo on Luxembourg collaboration. As the historian Henri Wehenkel writes: " distinction was made between the good and the bad, those who were termed resistants and those who were termed collaborators. Very soon, a consensus came about to only mention the former and to subject the latter to a sort of civic death, to silence and anonymity. All Luxembourgers had resisted, no collaboration had taken place. National unity was re-established."

Since the 1980s, there has been a more nuanced state of affairs and the taboo has been at least partially lifted, as collaboration has been portrayed in works such as Roger Manderscheid's 1988 novel Schacko Klak, and the 1985 film Déi zwéi vum Bierg [lb]. However, it still remains a subject rarely dealt with among historians and in public discourse.

Cultural references

- Schacko Klak, 1988 novel by Roger Manderscheid

- Déi zwei vum Bierg, 1985 film

- Emil [lb], 2010 film by Marc Thoma

See also

- Volksdeutsche Bewegung (VdB)

- Collaboration with the Axis powers

- Luxembourg Resistance

- Luxembourg in World War II

References

- Bruch, Robert (30 May 1958). ""Spengelskrich" und "Gielemännchen"". d'Letzeburger Land (in German). Vol. 5, no. 22. p. 3. Retrieved 2 December 2023.

- ^ Majerus, Benoît. "Kollaboration in Luxemburg: die falsche Frage?" In: ...et wor alles net esou einfach - Questions sur le Luxembourg et la Deuxième Guerre mondiale; exhibition book, published by Musée d'Histoire de la Ville de Luxembourg, Vol. X; Luxembourg, 2002; p. 126–140.

- ^ Artuso, Vincent. "Double jeu". In: forum, No. 304 (February 2011). p. 26–28.

- Maas, Jacques. "Le groupe sidérurgique ARBED face à l’hégémonie nazie – Collaboration ou résistance?" In: Archives nationales (eds.). Collaboration: nazification? Le cas du Luxembourg à la lumière des situations française, belge et néerlandaise. Actes du colloque international, Centre culturel de rencontre Abbaye de Neumünster, May 2006. Luxembourg: Imprimerie Hengen, 2008.

- Wehenkel, Henri. "La collaboration impossible". In: forum, No. 257 (June 2006). p. 52

Further reading

- Archives nationales (eds.). Collaboration: nazification? Le cas du Luxembourg à la lumière des situations française, belge et néerlandaise. Actes du colloque international, Centre culturel de rencontre Abbaye de Neumünster, May 2006. 479 p. Luxembourg: Imprimerie Hengen, 2008.

- Artuso, Vincent. La collaboration au Luxembourg durant la Seconde Guerre mondiale (1940–1945): Accommodation, Adaptation, Assimilation. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang, 2013. ISBN 978-3-631-63256-7

- Cerf, Paul. De l’épuration au Luxembourg après la Seconde Guerre mondiale. Luxembourg: Imprimerie Saint-Paul, 1980.

- Dostert, Paul. Luxemburg zwischen Selbstbehauptung und nationaler Selbstaufgabe. Die deutsche Besatzungspolitik und die Volksdeutsche Bewegung 1940–1945. Luxembourg: Imprimerie Saint-Paul, 1985. 309 pages

- Krier, Émile. "Die Luxemburger Wirtschaft im Zweiten Weltkrieg". In: Hémecht, Vol. 39, 1987. p. 393–399.

- Majerus, Benoît. "Les Ortsgruppenleiter au Luxembourg. Essai d'une analyse socio-économique." In: Hémecht, Vol. 52, No. 1, 2000. p. 101–122

- Schoentgen, Marc. "'Heim ins Reich'? Die ARBED-Konzernleitung während der deutschen Besatzung 1940–1944: zwischen Kollaboration und Widerstand". In: forum, No. 304 (February 2011). p. 29–35

- Scuto, Denis. "Le 10 mai 1940 et ses mythes à revoir - Les autorités luxembourgeoises et la persécution des juifs au Grand-Duché en 1940". Tageblatt, 10/11 May 2014, p. 2–5

- Volkmann, Hans-Erich. Luxemburg im Zeichen des Hakenkreuzes. Eine politische Wirtschaftsgeschichte. 1933 bis 1944. Paderborn: Schöningh, 2010.

- Wey, Claude. Les fondements idéologiques et sociologiques de la collaboration luxembourgeoise pendant la Deuxième guerre mondiale. Paper written as part of the teaching practicum. Unpublished. Luxembourg 1981.