Medical condition

| Mandibular fracture | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Mandible fracture, fracture of the jaw |

| |

| 3D computed tomographic image of a mandible fracture in two places. One is a displaced right angle fracture and the other is a left parasymphyseal fracture. | |

| Specialty | Oral & Maxillofacial Surgery |

| Symptoms | Decreased ability to open the mouth, teeth will not align properly, bleeding of the gums |

| Usual onset | Males in their 30s |

| Causes | Trauma, osteonecrosis, tumors |

| Diagnostic method | Plain X-ray, Panorex, CT scan |

| Treatment | Surgery within a few days |

Mandibular fracture, also known as fracture of the jaw, is a break through the mandibular bone. In about 60% of cases the break occurs in two places. It may result in a decreased ability to fully open the mouth. Often the teeth will not feel properly aligned or there may be bleeding of the gums. Mandibular fractures occur most commonly among males in their 30s.

Mandibular fractures are typically the result of trauma. This can include a fall onto the chin or a hit from the side. Rarely they may be due to osteonecrosis or tumors in the bone. The most common area of fracture is at the condyle (36%), body (21%), angle (20%) and symphysis (14%). Rarely the fracture may occur at the ramus (3%) or coronoid process (2%). While a diagnosis can occasionally be made with plain X-ray, modern CT scans are more accurate.

Immediate surgery is not necessarily required. Occasionally people may go home and follow up for surgery in the next few days. A number of surgical techniques may be used including maxillomandibular fixation and open reduction internal fixation (ORIF). People are often put on antibiotics such as penicillin for a brief period of time. The evidence to support this practice; however, is poor.

Signs and symptoms

General

By far, the two most common symptoms described are pain and the feeling that teeth no longer correctly meet (traumatic malocclusion, or disocclusion). The teeth are very sensitive to pressure (proprioception), so even a small change in the location of the teeth will generate this sensation. People will also be very sensitive to touching the area of the jaw that is broken, or in the case of condylar fracture the area just in front of the tragus of the ear.

Other symptoms may include loose teeth (teeth on either side of the fracture will feel loose because the fracture is mobile), numbness (because the inferior alveolar nerve runs along the jaw and can be compressed by a fracture) and trismus (difficulty opening the mouth).

Outside the mouth, signs of swelling, bruising and deformity can all be seen. Condylar fractures are deep, so it is rare to see significant swelling although, the trauma can cause fracture of the bone on the anterior aspect of the external auditory meatus so bruising or bleeding can sometimes be seen in the ear canal. Mouth opening can be diminished (less than 3 cm). There can be numbness or altered sensation (anesthesia/paraesthesia in the chin and lower lip (the distribution of the mental nerve).

Intraorally, if the fracture occurs in the tooth bearing area, a step may seen between the teeth on either side of the fracture or a space can be seen (often mistaken for a lost tooth) and bleeding from the gingiva in the area. There can be an open bite where the lower teeth, no longer meet the upper teeth. In the case of a unilateral condylar fracture the back teeth on the side of the fracture will meet and the open bite will get progressively greater towards the other side of the mouth.

Sometimes bruising will develop in the floor of the mouth (sublingual eccymosis) and the fracture can be moved by moving either side of the fracture segment up and down. For fractures that occur in the non-tooth bearing area (condyle, ramus, and sometimes the angle) an open bite is an important clinical feature since little else, other than swelling, may be apparent.

Condylar

This type of fractured mandible can involve one condyle (unilateral) or both (bilateral). Unilateral condylar fracture may cause restricted and painful jaw movement. There may be swelling over the temporomandibular joint region and bleeding from the ear because of lacerations to the external auditory meatus. The hematoma may spread downwards and backwards behind the ear, which may be confused with Battle's sign (a sign of a base of skull fracture), although this is an uncommon finding so if present, intra-cranial injury must be ruled out. If the bones fracture and overlie each other there may be shortening of the height of the ramus. This results in gagging of the teeth on the fractured side (the teeth meet too soon on the fractured side, and not on the non fractured side, i.e. "open bite" that becomes progressively worse to the unaffected side). When the mouth is opened, there may be deviation of the mandible towards the fractured side. Bilateral condylar fractures may cause the above signs and symptoms, but on both sides. Malocclusion and restricted jaw movement are usually more severe. Bilateral body or parasymphysis fractures are sometimes termed "flail mandible", and can cause involuntary posterior movement of the tongue with subsequent obstruction of the upper airway. Displacement of the condyle through the roof of the glenoid fossa and into the middle cranial fossa is rare. Other rare complications of mandibular trauma include internal carotid artery injury, and obliteration of the ear canal due to posterior condylar dislocation. Bilateral condylar fractures combined with a symphyseal fracture is sometimes termed a guardsman's fracture. The name comes from this injury occurring in soldiers who faint on parade grounds and strike the floor with their chin.

Diagnosis

Plain film radiography

Traditionally, plain films of the mandible would be exposed but had lower sensitivity and specificity owing to overlap of structures. Views included AP (for parasymphsis), lateral oblique (body, ramus, angle, coronoid process) and Towne's (condyle) views. Condylar fractures can be especially difficult to identify, depending on the direction of condylar displacement or dislocation so multiple views of it are usually examined with two views at perpendicular angles.

Panoramic radiography

Panoramic radiographs are tomograms where the mandible is in the focal trough and show a flat image of the mandible. Because the curve of the mandible appears in a 2-dimensional image, fractures are easier to spot leading to an accuracy similar to CT except in the condyle region. In addition, broken, missing or malaligned teeth can often be appreciated on a panoramic image which is frequently lost in plain films. Medial/lateral displacement of the fracture segments and especially the condyle are difficult to gauge so the view is sometimes augmented with plain film radiography or computed tomography for more complex mandible fractures.

Computed tomography

Computed tomography is the most sensitive and specific of the imaging techniques. The facial bones can be visualized as slices through the skeletal in either the axial, coronal or sagittal planes. Images can be reconstructed into a 3-dimensional view, to give a better sense of the displacement of various fragments. 3D reconstruction, however, can mask smaller fractures owing to volume averaging, scatter artifact and surrounding structures simply blocking the view of underlying areas.

Research has shown that panoramic radiography is similar to computed tomography in its diagnostic accuracy for mandible fractures and both are more accurate than plain film radiograph. The indications to use CT for mandible fracture vary by region, but it does not seem to add to diagnosis or treatment planning except for comminuted or avulsive type fractures, although, there is better clinician agreement on the location and absence of fractures with CT compared to panoramic radiography.

-

Panoramic radiograph of a simple mandible fracture of the right mandibular body, minimally displaced. Note that the teeth to the left of the fracture do not touch

Panoramic radiograph of a simple mandible fracture of the right mandibular body, minimally displaced. Note that the teeth to the left of the fracture do not touch

-

lateral oblique image demonstrating a fractured mandible.

-

Towne's view of a bilateral condyle fracture. White arrow is a fracture on the neck of the condyle. Black arrow shows the condyle pulled to the medial. The same injury can be seen on the opposite side

Towne's view of a bilateral condyle fracture. White arrow is a fracture on the neck of the condyle. Black arrow shows the condyle pulled to the medial. The same injury can be seen on the opposite side

-

3D CT reconstruction of mandible fracture, white arrow marks fracture, red arrow marks moderate displacement and open bite

3D CT reconstruction of mandible fracture, white arrow marks fracture, red arrow marks moderate displacement and open bite

-

occlusal radiograph of a mandibular parasymphysis fracture

occlusal radiograph of a mandibular parasymphysis fracture

Classification

There are various classification systems of mandibular fractures in use.

Location

This is the most useful classification, because both the signs and symptoms, and also the treatment are dependent upon the location of the fracture. The mandible is usually divided into the following zones for the purpose of describing the location of a fracture (see diagram): condylar, coronoid process, ramus, angle of mandible, body (molar and premolar areas), parasymphysis and symphysis.

Alveolar

This type of fracture involves the alveolus, also termed the alveolar process of the mandible.

Condylar

Condylar fractures are classified by location compared to the capsule of ligaments that hold the temporomandibular joint (intracapsular or extracapsular), dislocation (whether or not the condylar head has come out of the socket (glenoid fossa) as the muscles (lateral pterygoid) tend to pull the condyle anterior and medial) and neck of the condyle fractures. E.g. extracapsular, non-displaced, neck fracture. Pediatric condylar fractures have special protocols for management.

Coronoid

Because the coronoid process of the mandible lies deep to many structures, including the zygomatic complex (ZMC), it is rare to be broken in isolation. It usually occurs with other mandibular fractures or with fracture of the zygomatic complex or arch. Isolated fractures of the coronoid process should be viewed with suspicion and fracture of the ZMC should be ruled out.

Ramus

Ramus fractures are said to involve a region inferiorly bounded by an oblique line extending from the lower third molar (wisdom tooth) region to the posteroinferior attachment of the masseter muscle, and which could not be better classified as either condylar or coronoid fractures.

Angle

The angle of the mandible refers to the angle created by the arrangement of the body of the mandible and the ramus. Angle fractures are defined as those that involve a triangular region bounded by the anterior border of masseter muscle and an oblique line extending from the lower third molar (wisdom tooth) region to the posteroinferior attachment of the masseter muscle.

Body

Fractures of the mandibular body are defined as those that involve a region bounded anteriorly by the parasymphysis (defined as a vertical line just distal to the canine tooth) and posteriorly by the anterior border of the masseter muscle.

Parasymphysis

Parasymphyseal fractures are defined as mandibular fractures that involve a region bounded bilaterally by vertical lines just distal to the canine tooth.

Symphysis

Symphyseal fractures are a linear fractures that run in the midline of the mandible (the symphysis).

Fracture type

Mandibular fractures are also classified according to categories that describe the condition of the bone fragments at the fracture site and also the presence of communication with the external environment.

Greenstick

Greenstick fractures are incomplete fractures of flexible bone, and for this reason typically occur only in children. This type of fracture generally has limited mobility.

Simple

A simple fracture describes a complete transection of the bone with minimal fragmentation at the fracture site.

Comminuted

The opposite of a simple fracture is a comminuted fracture, where the bone has been shattered into fragments, or there are secondary fractures along the main fracture lines. High velocity injuries (e.g. those caused by bullets, improvised explosive devices, etc...) will frequently cause comminuted fractures.

Compound

A compound fracture is one that communicates with the external environment. In the case of mandibular fractures, communication may occur through the skin of the face or with the oral cavity. Mandibular fractures that involve the tooth-bearing portion of the jaw are by definition compound fractures, because there is at least a communication via the periodontal ligament with the oral cavity and with more displaced fractures there may be frank tearing of the gingival and alveolar mucosa.

Involvement of teeth

When a fracture occurs in the tooth bearing portion of the mandible, whether or not it is dentate or edentulous will affect treatment. Wiring of the teeth helps stabilize the fracture (either during placement of osteosynthesis or as a treatment by itself), so the lack of teeth will guide treatment. When an edentulous mandible (no teeth) is less than 1 cm in height (as measured on panoramic radiograph or CT scan) additional risks apply because the blood flow from the marrow (endosseous) is minimal and the healing bone must rely on blood supply from the periosteum surrounding the bone. If a fracture occurs in a child with mixed dentition different treatment protocols are needed.

Other fractures of the body, are classified as open or closed. Because fractures that involve the teeth, by definition, communicate with the mouth this distinction is largely lost in mandible fractures. Condylar, ramus, and coronoid process fractures are generally closed whereas angle, body and parasymphsis fractures are generally open.

Displacement

The degree to which the segments are separated. The larger the separation, the more difficult it is to bring them back together (approximate the segments)

Favourability

For angle and posterior body fractures, when the angle of the fracture line is angled back (more posterior at the top of the jaw and more anterior at the bottom of the jaw) the muscles tend to bring the fracture segments together. This is called favorable. When the angle of the fractures is pointing to the front, it is unfavorable.

Age of the fracture

While mandible fractures have similar complication rates whether treated immediately or days later, older fractures are believed to have higher non-union and infection rates although the data on this makes it difficult to draw firm conclusions.

Treatment

Like all fractures, consideration has to be given to other illnesses that might jeopardize the patient, then to reduction and fixation of the fracture itself. Except in avulsive type injuries, or those where there might be airway compromise, a several day delay in the treatment of mandible fractures seems to have little impact on the outcome or complication rates.

General considerations

Since mandible fractures are usually the result of blunt force trauma to the head and face, other injuries need to be considered before the mandible fracture. First and foremost is compromise of the airway. While rare, bilateral mandible fractures that are unstable can cause the tongue to fall back and block the airway. Fractures such as a symphyseal or bilateral parasymphyseal may lead to mobility of the central portion of the mandible where genioglossus attaches, and allow the tongue to fall backwards and block the airway. In larger fractures, or those from high velocity injuries, soft tissue swelling can block the airway.

In addition to the potential for airway compromise, the force delivered to break the jaw can be great enough to either fracture the cervical spine or cause intra-cranial injury (head injury). It is common for both to be assessed with facial fractures.

Finally, vascular injury can result (with particular attention to the internal carotid and jugular) from high velocity injuries or severely displaced mandible fractures.

Loss of consciousness combined with aspiration of tooth fragments, blood and possibly dentures mean that the airway may be threatened.

Reduction

Reduction refers to approximating the ends of the bones edges that are broken. This is done with either an open technique, where an incision is made, the fracture is found and is physically manipulated into place, or closed technique where no incision is made.

The mouth is unique, in that the teeth are well secured to the bone ends but come through epithelium (mucosa). A leg or wrist, for instance, has no such structure to help with a closed reduction. In addition, when the fracture happens to be in a tooth bearing area of the jaws, aligning the teeth well usually results in alignment of the fracture segments.

To align the teeth, circumdental wiring is often used where wire strands (typically 24 gauge or 26 gauge) are wrapped around each tooth then attached to a stainless steel arch bar. When the maxillary (top) and mandibular (bottom) teeth are aligned together, this brings the fracture segments into place. Higher tech solutions are also available, to help reduce the segments with arch bars using bonding technology.

Fixation

Simple fractures are usually treated with closed reduction and indirect skeletal fixation, more commonly referred to as maxillo-mandibular fixation (MMF). The closed reduction is explained above. The indirect skeletal fixation is accomplished by placing an arch bar, secured to the teeth on the maxillary and mandibular dentition, then securing the top and bottom arch bars with wire loops.

Many alternatives exist to secure the maxillary and mandibular dentition including resin bonded arch bars, Ivy loops (small eyelets of wires), orthodontic bands and MMF bone screws where titanium screws with holes in the head of them are screwed into the basal bone of the jaws then secured with wire.

Closed reduction with direct skeletal fixation follows the same premise as MMF except that wires are passed through the skin and around the bottom jaw in the mandibule and through the piriform rim or zygomatic buttresses of the maxilla then joined to secure the jaws. The option is sometimes used when a patient is edentulous (has no teeth) and rigid internal fixation cannot be used.

Open reduction with direct skeletal fixation allows the bones to be directly mandibulated through an incision so that the fractured ends meet, then they can be secured together either rigidly (with screws or plates and screws) or non-rigidly (with transosseous wires). There are a multitude of various plate and screw combinations including compression plates, non-compression plates, lag-screws, mini-plates and biodegradable plates.

External fixation, which can be used with either open or closed reduction uses a pin system, where long screws are passed through the skin and into either side of a fracture segment (typically 2 pins per side) then secured in place using an external fixator. This is a more common approach when the bone is heavily comminuted (shattered into small pieces, for instance in a bullet wound) and when the bone is infected (osteomyelitis).

Regardless of the method of fixation, the bone need to remain relatively stable for a period of 3–6 weeks. On average, the bone gains 80% of its strength by 3 weeks and 90% of it by 4 weeks. There is great variation depending on the severity of injury, health of the wound, and age of the patient.

-

Maxillomandibular fixation with circumdental wires, archbars and elastics for a condyle fracture

Maxillomandibular fixation with circumdental wires, archbars and elastics for a condyle fracture

-

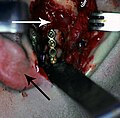

Rigid internal fixation of parasymphysis fracture of the mandible. White arrow marks fracture, black arrow marks arch bar on lower teeth

Rigid internal fixation of parasymphysis fracture of the mandible. White arrow marks fracture, black arrow marks arch bar on lower teeth

-

Rigid internal fixation of right condyle fracture with mini-plate on the neck of the condyle. Black arrow marks right earlobe, white arrow marks head of the condyle

Rigid internal fixation of right condyle fracture with mini-plate on the neck of the condyle. Black arrow marks right earlobe, white arrow marks head of the condyle

-

External fixation of left mandible fracture

External fixation of left mandible fracture

Current clinical evidence

A 2013 Cochrane review assessed clinical studies on surgical (open reduction) and non-surgical (closed reduction) management of mandible fractures that do not involve the condyle. The review found insufficient evidence to recommend the effectiveness of any single intervention.

Special considerations

Condyle

The best treatment for condylar fractures is controversial. There are two main options, namely closed reduction or open reduction and fixation. Closed reduction may involve intermaxillary fixation, where the jaws are splinted together in the correct position for a period of weeks. Open reduction involves surgical exposure of the fracture site, which can be carried out via incisions within the mouth or incisions outside the mouth over the area of the condyle. Open reduction is sometimes combined with use of an endoscope to aid visualization of fracture site. Although closed reduction carries a risk of the bone healing out of position, with consequent alteration of the bite or the creation of facial asymmetry, it does not risk temporary damage to the facial nerve or result in any facial scar that accompanies open reduction. A systematic review was unable to find sufficient evidence of the superiority of one method over another in the management of condylar fractures. Paediatric condylar fractures are especially problematic, owing to the remaining growth potential and possibility of ankylosis of the joint. Early mobilization is often recommended as in the Walker protocol.

Edentulous mandible

A broken jaw that has no teeth in it faces two additional issues. First, the lack of teeth makes reduction and fixation using MMF difficult. Instead of placing circumdental wires around the teeth, existing dentures can be left in (or Gunning splints, a type of temporary denture) and the mandible fixated to the maxilla using skeletal fixation (circummandibular and circumzygomatic wires) or using MMF bone screws. More commonly, open reduction and rigid internal fixation is placed.

When the width of the mandible is less than 1 cm, the jaw loses its endosteal blood supply. Instead, the blood supply comes largely from the periosteum. Open reduction (which normally strips the periosteum during the dissection) can lead to avascular necrosis. In these cases, oral surgeons sometimes opt for external fixation, closed reduction, supraperiosteal dissection or other techniques to maintain the periosteal blood flow.

High velocity injuries

In high velocity injuries, the soft tissue can be severely damaged far from the bullet wound itself due to hydrostatic shock. Because of this the airway must be carefully managed and vessels well examined. Because the jaw can be highly comminuted, MMF and rigid internal fixation can be difficult. Instead, external fixation is often used.

Pathologic fracture

Fractures where large cysts or tumours are in the area (and weaken the jaw), where there is an area of osteomyelitis or where osteonecrosis exist cause special challenges to fixation and healing. Cysts and tumours can limit effective bone to bone contact and osteomyelitis or osteonecrosis compromise blood supply to the bone. In all of the situations, healing will be delayed and sometimes, resection is the only alternative to treatment.

Prognosis

The healing time for a routine mandible fractures is 4–6 weeks whether MMF or rigid internal fixation (RIF) is used. For comparable fractures, patients who received MMF will lose more weight and take longer to regain mouth opening, whereas, those who receive RIF have higher infection rates.

The most common long-term complications are loss of sensation in the mandibular nerve, malocclusion and loss of teeth in the line of fracture. The more complicated the fracture (infection, comminution, displacement) the higher the risk of fracture.

Condylar fractures have higher rates of malocclusion which in turn are dependent on the degree of displacement and/or dislocation. When the fracture is intracapsular there is a higher rate of late-term osteoarthritis and the potential for ankylosis although the later is a rare complication as long as mobilization is early. Pediatric condylar fractures have higher rates of ankylosis and the potential for growth disturbance.

Rarely, mandibular fracture can lead to Frey's syndrome.

Epidemiology

Mandible fracture causes vary by the time period and the region studied. In North America, blunt force trauma (a punch) is the leading cause of mandible fracture whereas in India, motor vehicle collisions are now a leading cause. On battle grounds, it is more likely to be high velocity injuries (bullets and shrapnel). Prior to the routine use of seat belts, airbags and modern safety measures, motor vehicle collisions were a leading cause of facial trauma. The relationship to blunt force trauma explains why 80% of all mandible fractures occur in males. Mandibular fracture is a rare complication of third molar removal, and may occur during the procedure or afterwards. With respect to trauma patients, roughly 10% have some sort of facial fracture, the majority of which come from motor vehicle collisions. When the person is unrestrained in a car, the risk of fracture rises 50% and when an unhelmeted motorcyclist the risk rises 4-fold.

History

Management of mandible fractures has been mentioned as early as 1700 B.C. in the Edwin Smith Papyrus and later by Hippocrates in 460 B.C., "Displaced but incomplete fractures of the mandible where continuity of the bone is preserved should be reduced by pressing the lingual surface with the fingers...". Open reduction was described as early as 1869. Since the late 19th century, modern techniques including MMF (see above) have been described with titanium based rigid internal fixation becoming commonplace since the 1970s and biodegradable plates and screws being available since the 1980s.

References

- ^ Murray, JM (May 2013). "Mandible fractures and dental trauma". Emergency Medicine Clinics of North America. 31 (2): 553–73. doi:10.1016/j.emc.2013.02.002. PMID 23601489.

- Al-Moraissi, EA; Ellis E, 3rd (March 2015). "Surgical treatment of adult mandibular condylar fractures provides better outcomes than closed treatment: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 73 (3): 482–93. doi:10.1016/j.joms.2014.09.027. PMID 25577459.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Shridharani, SM; Berli, J; Manson, PN; Tufaro, AP; Rodriguez, ED (September 2015). "The Role of Postoperative Antibiotics in Mandible Fractures: A Systematic Review of the Literature". Annals of Plastic Surgery. 75 (3): 353–7. doi:10.1097/sap.0000000000000135. PMID 24691320. S2CID 31089018.

- Kyzas, PA (April 2011). "Use of antibiotics in the treatment of mandible fractures: a systematic review". Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 69 (4): 1129–45. doi:10.1016/j.joms.2010.02.059. PMID 20727642.

- Fonseca RJ, Barber HD, Powers MP, Frost DE (2012). Oral & maxillofacial trauma (4th ed.). W B Saunders Co. ISBN 9781455705542.

- ^ Banks P, Brown A; Brown, Andrew E. (2000). Fractures of the facial skeleton. Oxford: Wright. pp. 1–4, 10–14, 17–20, 42–47, 68, 81–119. ISBN 978-0723610342.

- Stewart, Michael G., ed. (2005). Head, face and neck trauma comprehensive management. Stuttgart: Thieme. p. 107. ISBN 9783131403315. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

- Barron, RP; Kainulainen, VT; Gusenbauer, AW; Hollenberg, R; Sàndor, GK (December 2002). "Management of traumatic dislocation of the mandibular condyle into the middle cranial fossa" (PDF). Journal (Canadian Dental Association). 68 (11): 676–80. PMID 12513935. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 October 2013.

- Tveita, Ingrid Aune; Madsen, Martin Ragnar Skjerve; Nielsen, Erik Waage (2017). "Dissection of the internal carotid artery and stroke after mandibular fractures: A case report and review of the literature". Journal of Medical Case Reports. 11 (1): 148. doi:10.1186/s13256-017-1316-1. PMC 5455209. PMID 28576125.

- Ritesh Kalaskar, Ashita & Kalaskar, Ritesh. (2017). Isolated tympanic plate fracture detected by cone-beam computed tomography: report of four cases with review of literature. Journal of the Korean Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons. 43. 356. DOI: 10.5125/jkaoms.2017.43.5.356.

- White, Stuart; Pharoah, Michael J (2000). Oral Radiology Principals & Interpretation. St. Louis, Missouri: Mosby. ISBN 978-0-323-02001-5.

- Nair, M. K.; Nair, U. P. (2001). "Imaging of mandibular trauma: ROC analysis". Academic Emergency Medicine. 8 (7): 689–695. doi:10.1111/j.1553-2712.2001.tb00186.x. PMID 11435182.

- Laskin, Daniel (2007). Decision making in oral and maxillofacial surgery. Chicago: Quintessence Pub. Co. ISBN 978-0-86715-463-4.

- Roth, F. S.; Kokoska, M. S.; Awwad, E. E.; Martin, D. S.; Olson, G. T.; Hollier, L. H.; Hollenbeak, C. S. (2005). "The identification of mandible fractures by helical computed tomography and panorex tomography". The Journal of Craniofacial Surgery. 16 (3): 394–399. doi:10.1097/01.scs.0000171964.01616.a8. PMID 15915103. S2CID 11089616.

- Abdel-Galil, K.; Loukota, R. (2010). "Fractures of the mandibular condyle: Evidence base and current concepts of management". British Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 48 (7): 520–526. doi:10.1016/j.bjoms.2009.10.010. PMID 19900741.

- Vanhove, F.; Dom, M.; Wackens, G. (1997). "Fracture of the coronoid process: Report of a case". Acta Stomatologica Belgica. 94 (2): 81–85. PMID 11799592.

- Goodday, Reginald H. B. (1 November 2013). "Management of Fractures of the Mandibular Body and Symphysis". Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Clinics of North America. Trauma and Reconstruction. 25 (4): 601–616. doi:10.1016/j.coms.2013.07.002. ISSN 1042-3699. PMID 24021623.

- Goodday, Reginald H. B. (1 November 2013). "Management of Fractures of the Mandibular Body and Symphysis". Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Clinics of North America. Trauma and Reconstruction. 25 (4): 601–616. doi:10.1016/j.coms.2013.07.002. ISSN 1042-3699. PMID 24021623.

- ^ Hupp JR, Ellis E, Tucker MR (2008). Contemporary oral and maxillofacial surgery (5th ed.). St. Louis, Mo.: Mosby Elsevier. pp. 493–495, 499–500, 502–507. ISBN 9780323049030.

- Abreu, ME; Viegas, VN; Ibrahim, D; Valiati, R; Heitz, C; Pagnoncelli, RM; Silva, DN (1 May 2009). "Treatment of comminuted mandibular fractures: a critical review" (PDF). Medicina Oral, Patologia Oral y Cirugia Bucal. 14 (5): E247–51. PMID 19218899. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 March 2016.

- Nasser, M.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Ebadifar, A. (2007). Nasser, Mona (ed.). "Management of the fractured edentulous atrophic mandible". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1): CD006087. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006087.pub2. PMID 17253578.

- ^ Goth, S.; Sawatari, Y.; Peleg, M. (2012). "Management of Pediatric Mandible Fractures". Journal of Craniofacial Surgery. 23 (1): 47–56. doi:10.1097/SCS.0b013e318240c8ab. PMID 22337373. S2CID 25488743.

- Pektas, Z. O.; Bayram, B.; Balcik, C.; Develi, T.; Uckan, S. (2012). "Effects of different mandibular fracture patterns on the stability of miniplate screw fixation in angle mandibular fractures". International Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 41 (3): 339–343. doi:10.1016/j.ijom.2011.11.008. PMID 22178275.

- Hermund, N. U.; Hillerup, S. R.; Kofod, T.; Schwartz, O.; Andreasen, J. O. (2008). "Effect of early or delayed treatment upon healing of mandibular fractures: A systematic literature review". Dental Traumatology. 24 (1): 22–26. doi:10.1111/j.1600-9657.2006.00499.x. PMID 18173660.

- Williams, J Llewellyn (1994). Rowe and Williams' Maxillofacial Injuries. London: Churchhill Livingstone. p. 283. ISBN 978-0-443-04591-2.

- Nasser, Mona; Pandis, Nikolaos; Fleming, Padhraig S.; Fedorowicz, Zbys; Ellis, Edward; Ali, Kamran (8 July 2013). "Interventions for the management of mandibular fractures". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (7): CD006087. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006087.pub3. hdl:10026.1/9565. ISSN 1469-493X. PMID 23835608.

- ^ Sharif, MO; Fedorowicz, Z; Drews, P; Nasser, M; Dorri, M; Newton, T; Oliver, R (14 April 2010). "Interventions for the treatment of fractures of the mandibular condyle". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (4): CD006538. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006538.pub2. PMID 20393948.

- Andersson, Lars (2012). Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-29256-3.

- Myall, R. W. T. (2009). "Management of Mandibular Fractures in Children". Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Clinics of North America. 21 (2): 197–201, vi. doi:10.1016/j.coms.2008.12.007. PMID 19348985.

- Madsen, M. J.; Haug, R. H.; Christensen, B. S.; Aldridge, E. (2009). "Management of Atrophic Mandible Fractures". Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Clinics of North America. 21 (2): 175–183, v. doi:10.1016/j.coms.2008.12.006. PMID 19348982.

- Peleg, M.; Sawatari, Y. (2010). "Management of Gunshot Wounds to the Mandible". Journal of Craniofacial Surgery. 21 (4): 1252–1256. doi:10.1097/SCS.0b013e3181e2065b. PMID 20613603. S2CID 25154746.

- Alpert, B.; Tiwana, P. S.; Kushner, G. M. (2009). "Management of Comminuted Fractures of the Mandible". Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Clinics of North America. 21 (2): 185–192, v. doi:10.1016/j.coms.2008.12.002. PMID 19348983.

- Ezsiás, A.; Sugar, A. W. (1994). "Pathological fractures of the mandible: A diagnostic and treatment dilemma". The British Journal of Oral & Maxillofacial Surgery. 32 (5): 303–306. doi:10.1016/0266-4356(94)90051-5. PMID 7999738.

- Kyrgidis, A.; Koloutsos, G.; Kommata, A.; Lazarides, N.; Antoniades, K. (2013). "Incidence, aetiology, treatment outcome and complications of maxillofacial fractures. A retrospective study from Northern Greece". Journal of Cranio-Maxillofacial Surgery. 41 (7): 637–43. doi:10.1016/j.jcms.2012.11.046. PMID 23332470.

- Glazer, M.; Joshua, B. Z.; Woldenberg, Y.; Bodner, L. (2011). "Mandibular fractures in children: Analysis of 61 cases and review of the literature". International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology. 75 (1): 62–64. doi:10.1016/j.ijporl.2010.10.008. PMID 21035876.

- Kragstrup, Tue W.; Christensen, Jennifer; Fejerskov, Karin; Wenzel, Ann (August 2011). "Frey Syndrome—An Underreported Complication to Closed Treatment of Mandibular Condyle Fracture? Case Report and Literature Review" (PDF). Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 69 (8): 2211–2216. doi:10.1016/j.joms.2010.12.033. PMID 21496996.

- Kruger, Gustav (1984). Textbook of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. St. Louis, Missouri: CV Mosby. ISBN 978-0-8016-2793-4.

- Natu, S. S.; Pradhan, H.; Gupta, H.; Alam, S.; Gupta, S.; Pradhan, R.; Mohammad, S.; Kohli, M.; Sinha, V. P.; Shankar, R.; Agarwal, A. (2012). "An Epidemiological Study on Pattern and Incidence of Mandibular Fractures". Plastic Surgery International. 2012: 1–7. doi:10.1155/2012/834364. PMC 3503282. PMID 23227327.

- Berkowitz, I.; Bornman, P. C.; Kottler, R. E. (2008). "Cystic Duct Entry - Another Cause of Pseudocalculus". Endoscopy. 22 (2): 85–87. doi:10.1055/s-2007-1012801. PMID 2335148. S2CID 260127649.

- Ethunandan, M; Shanahan, D; Patel, M (24 February 2012). "Iatrogenic mandibular fractures following removal of impacted third molars: an analysis of 130 cases". British Dental Journal. 212 (4): 179–84. doi:10.1038/sj.bdj.2012.135. PMID 22361547. S2CID 2997748.

- Wilson, William C (2007). Trauma: Emergency Resuscitation, Perioperative Anesthesia, Surgical Management (Volume 1). Google eBooks: Informa Healthcare. pp. 417–418. ISBN 978-1-280-73024-5.

- Wilson, William C (2007). Trauma: Emergency Resuscitation, Perioperative Anesthesia, Surgical Management (Volume 1). Google eBooks: Informa Healthcare. p. 417. ISBN 978-1-280-73024-5.

External links

| Classification | D |

|---|