| Melchor Rodríguez García | |

|---|---|

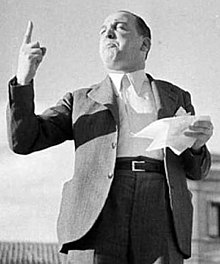

Rodríguez in 1936 Rodríguez in 1936 | |

| Mayor of Madrid | |

| In office March 28, 1939 c. hours | |

| Preceded by | Rafael Henche de la Plata |

| Succeeded by | Alberto Alcocer y Ribacoba |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Melchor Rodríguez García (1893-05-30)May 30, 1893 Seville, Spain |

| Died | February 14, 1972(1972-02-14) (aged 78) Madrid, Spain |

| Resting place | San Justo Cemetery |

| Political party | CNT |

Melchor Rodríguez García (30 May 1893 —14 February 1972), also known by his nickname of The Red Angel (Spanish: El Ángel Rojo), was a Spanish politician, trade unionist, and notable anarcho-syndicalist, who served as the head of prison authorities in Madrid during the Spanish Civil War. He was also the last Mayor of Madrid before the Francoist forces took over the city.

Early life, education, and early career

Early life and family

Melchor Rodríguez García, was born on 30 May 1893, in the Triana neighborhood of Seville, Spain. His father was Isidoro Rodríguez, who died in an accident on the docks of the Guadalquivir. His mother was a seamstress and cigar maker who took care of Melchor and his two brothers.

Education and early career

Rodríguez studied at the asylum school. When he was thirteen years old, he began to work as a coppersmith in a workshop in Seville. He attempted to become a bullfighter and left his home to visit various fairs. El Cossío (the bullfighting encyclopedia) contains a reference to Rodríguez, cited as the only right-hander who combined bullfighting with politics. Rodríguez fought in Sanlúcar de Barrameda in 1913, and later in increasingly important squares until he reached the Puerta de Alcalá bullring. There he suffered a serious injury in August 1918. He retired in 1920, after some more bullfights in Salamanca and Seville.

After his bullfighting career, Rodríguez moved to Madrid in 1921, where he began to work as a sheet metal worker. Around this time, he joined the Unión General de Trabajadores (UGT). He began to be attracted to the Labor Movement and joined the Confederación Nacional del Trabajo (CNT). Shortly after, he was appointed president of the Anarchist Trade Union of Carrocera. He began the fight for the rights of inmates, a fight that would cost him time in prison during the monarchy and the Second Republic.

Head of the Prison authorities

Appointment

After the outbreak of the Civil War, on 5 December 1936, Juan García Oliver appointed Rodríguez García director of the prisons of Madrid, as one of the anarchists to be accepted into the government for their support of the republicans.

Tenure

He was responsible not only for the upkeep of the prisoners and prevention of escapes, but more importantly for prevention of lynching, proposed by numerous members of various militias.

People in besieged Madrid reacted with violence toward imprisoned nationalists after particularly bloody bombardments or after the press reported the nationalist treatment of republican prisoners. The most notable of such massacres happened after the air raid on Alcalá de Henares air base in December 1936. Protesters, some of whom were armed, arrived at one of Madrid's prisons, stormed the gates, and demanded that the cells be opened and the nationalist prisoners be handed to the crowd. Rodríguez appeared at the prison, ordered the crowd to disperse, and announced that he would rather give arms to the prisoners than hand them over to the mob. Among the prisoners Rodríguez saved were notable football player Ricardo Zamora and political leaders of the Falange Española, such as Rafael Sánchez Mazas, Ramón Serrano Súñer, Valentín Galarza Morante, and Raimundo Fernández-Cuesta. During his term in office, Melchor Rodríguez García revealed that José Cazorla Maure, a counsellor of state security of the Council of Defence of Madrid, had organized a net of private, illegal prisons that the Communist Party of Spain ran.

Rodríguez was appointed councilor of Madrid. He represented the Iberian Anarchist Federation. Segismundo Casado appointed him Mayor of Madrid in the last days of the war, and he was in charge of handing over power to the Francoists when Madrid fell on March 28, 1939.

Trial and imprisonment

After the war, Rodríguez did not escape the repression that the defeated suffered. He was arrested and tried twice by court martial. After an acquittal in the first trial, the prosecutor appealed. Rodríguez received a sentence of twenty years and one day, of which he served four years. At this second Council of War, General Agustín Muñoz Grandes, whom Rodríguez had saved, with other military prisoners, during the war spoke in favor of Rodríguez and possibly saved his life. At the end of the Council of War, during which the prosecutor requested the death penalty for Rodríguez, the prosecutor asked if anyone present had anything to allege. Muñoz stood, introduced himself as a Lieutenant General in the Army, and with his testimony presented thousands of signatures of people whom Rodríguez had saved, in some cases at Rodríguez's personal risk. Rodríguez was in the Porlier prison and in the El Puerto de Santa María prison, from which he was provisionally released in 1944.

Death

He died on 14 February 1972, in Madrid, Spain. He was buried at the San Justo cemetery. At the funeral, hundreds of people gathered, including figures from the dictatorship and fellow anarchists. For the only time during Francisco Franco's regime, burial included an anarchist flag.

Commemoration

In 2016 Madrid City Council unanimously decided to name one of Madrid's streets after him.

References

- Santillán 1979, p. 475

- ^ MELCHOR RODRIGUEZ, “The Red Angel.”

- Beevor 2006, p. 173

- Beevor 2006, p. 260

- "Erasing Franco's memory one street at a time". BBC News. 2016-02-12. Retrieved 2022-09-14.

Bibliography

- Beevor, Antony (2006). The Battle for Spain: The Spanish Civil War 1936-1939. Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-303765-X.

- Santillán, Diego Abad de (1979). Alfonso XIII, la II república, Francisco Franco (in Spanish). Ediciones Júcar. ISBN 978-84-334-5516-1.