| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Mercure de France" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (March 2021) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

| French and Francophone literature |

|---|

| by category |

| History |

| Movements |

| Writers |

| Countries and regions |

| Portals |

The Mercure de France (French pronunciation: [mɛʁkyʁ də fʁɑ̃s]) was originally a French gazette and literary magazine first published in the 17th century, but after several incarnations has evolved as a publisher, and is now part of the Éditions Gallimard publishing group.

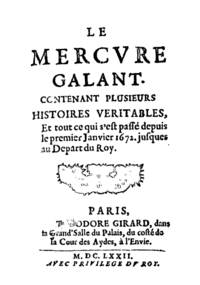

The gazette was published from 1672 to 1724 (with an interruption in 1674–1677) under the title Mercure galant (sometimes spelled Mercure gallant; 1672–1674) and Nouveau Mercure galant (1677–1724). The title was changed to Mercure de France in 1724. The gazette was briefly suppressed (under Napoleon) from 1811 to 1815 and ceased publication in 1825. The name was revived in 1890 for both a literary review and (in 1894) a publishing house initially linked with the symbolist movement. Since 1995 Mercure de France has been part of the Éditions Gallimard publishing group.

The original Mercure galant and Mercure de France

The Mercure galant was founded by the writer Jean Donneau de Visé in 1672. He directed the publication until his death in 1710. The name refers to the god Mercury, the messenger of the gods; the title also echos the Mercure françoys which was France's first literary gazette, founded in 1611 by the Paris bookseller J. Richer.

The magazine's goal was to inform elegant society about life in the court and intellectual/artistic debates; the gazette (which appeared irregularly) featured poems, anecdotes, news (marriages, gossip), theatre and art reviews, songs, and fashion reviews, and it became fashionable (and sometimes scandalous) to be mentioned in its pages. Publication stopped in 1674, but began again as a monthly with the name Nouveau Mercure galant in 1677.

The Mercure galant was a significant development in the history of journalism (it was the first gazette to report on the fashion world and played a pivotal role in the dissemination of news about fashion, luxury goods, etiquette and court life under Louis XIV to the provinces and abroad. The newspaper published propaganda intended to bolster Louis XIV and promote his domestic and foreign policies. In the 1670s, articles on the new season's fashions were also accompanied with engravings. The August 1697 edition contains a detailed description of a popular new puzzle, now known as peg solitaire. This article is the earliest known reference to peg solitaire.

The gazette was frequently denigrated by authors of the period. The name Mercure galant was used by the playwright Edmé Boursault for one of his plays critical of social pretensions; when Donneau de Visé complained, Boursault retitled his play Comédie sans titre (Play without a title).

The gazette played an important role in the "Quarrel of the Ancients and the Moderns", a debate on whether the arts and literature of the 17th century had achieved more than the illustrious writers and artists of antiquity, which would last until the beginning of the eighteenth century. Bernard le Bovier de Fontenelle and the Mercure galant joined the "Moderns". Nicolas Boileau-Despréaux was pushed into the role of champion of the "Anciens", and Jean Racine, Jean de La Fontaine and Jean de La Bruyère (who is famous for a jibe against the gazette: "le Mercure... est immédiatement au dessous de rien" ) took his defense.

The periodical eventually became a financial success and it brought Donneau de Visé comfortable revenues. The Mercure de France became the uncontested arbiter of French arts and humanities, and it has been called the most important literary journal in prerevolutionary France.

Thomas Corneille was a frequent contributor to the gazette. The Mercure continued to be published after Donneau de Visé's death in 1710. In 1724 its title was changed to Mercure de France and it developed a semi-official character with a governmentally appointed editor (profits were invested into pensions for writers). Jean-François de la Harpe was the editor in chief for 20 years; he also collaborated with Jacques Mallet du Pan. Other significant editors and contributors include: Marmontel, Raynal, Chamfort and Voltaire.

It is on the pages of the May 1734 issue of the Mercure de France that the term "Baroque" makes its first attested appearance – used (in pejorative way) in an anonymous, satirical review of Jean-Philippe Rameau’s Hippolyte et Aricie.

Right before the revolution, management was handed over to Charles-Joseph Panckoucke. During the revolutionary era, the title was changed briefly to Le Mercure français. Napoleon stopped its publication in 1811, but the review was resurrected in 1815. The review was last published in 1825.

The modern Mercure de France

| Parent company | Éditions Gallimard |

|---|---|

| Founded | 1890 |

| Founder | Alfred Vallette |

| Country of origin | France |

| Headquarters location | Paris |

| Publication types | Books |

| Official website | www |

History

At the end of the 19th century, the name Mercure de France was revived by Alfred Vallette. Vallette was closely linked to a group of writers associated with Symbolism who regularly met at the café la Mère Clarisse in Paris (rue Jacob), and which included: Jean Moréas, Ernest Raynaud, Paul Arène, Remy de Gourmont, Alfred Jarry, Albert Samain and Charles Cros. The first edition of the review appeared on January 1, 1890.

Over the next decade, the review achieved critical success, and poets such as Stéphane Mallarmé and José-Maria de Heredia published original works in it. The review became bimonthly in 1905.

In 1889, Alfred Vallette married the novelist Rachilde whose novel Monsieur Vénus was condemned on moral grounds. Rachilde was a member of the editorial committee of the review until 1924 and her personality and works did much to publicize the review. Rachilde held a salon on Tuesdays, and these "mardis du Mercure" would become famous for the authors who attended.

Like other reviews of the period, the Mercure also began to publish books (beginning in 1894). Along with works by symbolists, the Mercure brought out the first French translations of Friedrich Nietzsche, the first works of André Gide, Paul Claudel, Colette and Guillaume Apollinaire and the poems of Tristan Klingsor. Later publications include works by: Henri Michaux, Pierre Reverdy, Pierre-Jean Jouve, Louis-René des Forêts, Pierre Klossowski, André du Bouchet, Georges Séféris, Eugène Ionesco and Yves Bonnefoy.

With the death of Vallette in 1935, the management was taken over by Georges Duhamel (who had been editing the review since 1912). In 1938, because of Duhamel's anti-war stance, he was replaced by Jacques Antoine Bernard (in 1945, Bernard would be arrested and condemned for collaboration with the Germans). After the war, Duhamel (who was majority stockholder of the publishing house) appointed Paul Hartmann, who had participated in the resistance and clandestine publishing during the war, to run the review.

In 1958, the Éditions Gallimard publishing group bought the Mercure de France and Simone Gallimard was chosen as its director. In 1995, Isabelle Gallimard took over direction of the publishing house.

Literary Prizes

Mercure de France has won awards with the following authors:

- Salvat Etchart (Prix Renaudot 1967)

- Claude Faraggi (Prix Fémina 1975)

- Michel Butel (Prix Médicis 1977)

- Jocelyne François (Prix Fémina 1980)

- François-Olivier Rousseau (Prix Médicis and Prix Marcel Proust 1981)

- Nicolas Bréhal (Prix Valery Larbaud 1992)

- Paula Jacques (Prix Fémina 1991)

- Dominique Bona (Prix Interallié 1992)

- Andreï Makine (Prix Goncourt and Prix Médicis 1995)

- Gilles Leroy (Prix Goncourt 2007)

- Romain Gary published his novels under the penname Émile Ajar (with the complicity of Simone Gallimard) which allowed him to win an unprecedented two Prix Goncourt.

Book series

- Les romantiques allemands (1942)

- Collection ivoire (1964)

- Domaine anglais (1964)

- Collection bleue (1989)

- Collection poésie (1990)

- Bibliothèque américaine (1993)

- Le Petit Mercure (1995) : series in pocket format of short texts which welcomes different literary genres

- Bibliothèque étrangère (1999)

- Le Temps retrouvé poche (1999) & Le Temps retrouvé (2003) : newspapers, memoirs, travel books, letters, eye witness accounts

- Le goût de… (2002): literary anthologies devoted to towns, regions, countries and to numerous themes

- Traits et portraits (2002): autobiographical stories

References

- ^ Steinberger, Deborah (2022). "'Fake News' in Seventeenth-Century France: The Case of Le Mercure galant". Past & Present (Supplement_16): 143–171. doi:10.1093/pastj/gtac032. ISSN 0031-2746.

- DeJean, page 47.

- DeJean, page 63.

- Darnton, Robert; Roche, Daniel (1989). Revolution in Print: The Press in France 1775–1800. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. p. 148. ISBN 0-520-06431-3.

The bulk of this article is based on the French Misplaced Pages article, which is itself taken from the history page of the website of the Mercure de France (see external links). Additional information based on:

- DeJean, Joan. The Essence of Style: How the French Invented Fashion, Fine Food, Chic Cafés, Style, Sophistication, and Glamour. New York: Free Press, 2005 ISBN 978-0-7432-6414-3

- Harvey, Paul and J.E. Heseltine, eds. The Oxford Compagnon to French Literature. London: Oxford University Press, 1959.

- Patrick Dandrey, ed. Dictionnaire des lettres françaises: Le XVIIe siècle. Collection: La Pochothèque. Paris: Fayard, 1996.

External links

- Official website

- Le Mercure de France online from 1672 to 1674, from 1678 to 1682, from 1724 to 1791 and from 1890 to 1935 in Gallica, the digital library of the BnF.