| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Microfiber" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (March 2023) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Microfiber (microfibre in British English) is synthetic fibre finer than one denier or decitex/thread, having a diameter of less than ten micrometers.

The most common types of microfiber are made variously of polyesters; polyamides (e.g., nylon, Kevlar, Nomex); and combinations of polyester, polyamide, and polypropylene. Microfiber is used to make mats, knits, and weaves, for apparel, upholstery, industrial filters, and cleaning products. The shape, size, and combinations of synthetic fibers are chosen for specific characteristics, including softness, toughness, absorption, water repellence, electrostatics, and filtering ability.

They are commonly used for cleaning scratch prone surfaces such as displays, glass, and lenses. Microfiber cloth makes use of van der Waals force to remove dirt without scratches.

History

Production of ultra-fine fibers (finer than 0.7 denier) dates to the late 1950s, using melt-blown spinning and flash spinning techniques. Initially, only fine staples of random length could be manufactured and very few applications were found. Then came experiments to produce ultra-fine fibers of a continuous filament: the most promising experiments were made in Japan in the 1960s, by Miyoshi Okamoto, a scientist at Toray Industries. Okamoto's discoveries and those of Toyohiko Hikota led to many industrial applications, including Ultrasuede, one of the first successful synthetic microfibers, which entered the market in the 1970s. Microfiber's use in the textile industry then expanded. Microfibers were first publicized in the early 1990s, in Sweden, and saw success as a product in Europe over the course of the decade.

Apparel

Clothing

Microfiber fabrics are man-made and frequently used for athletic wear, such as cycling jerseys, because the microfiber material wicks moisture (perspiration) away from the body; subsequent evaporation cools the wearer.

Microfiber can be used to make tough, very soft fabric for clothing, often used in skirts, jackets, bathrobes, and swimwear. Microfiber can be made into Ultrasuede, a synthetic imitation of suede leather, which is cheaper and easier to clean and sew than natural suede leather.

Accessories

Microfiber is used to make many accessories that traditionally have been made from leather: wallets, handbags, backpacks, book covers, shoes, cell phone cases, and coin purses. Microfiber fabric is lightweight, durable, and somewhat water repellent, so it makes a good substitute.

Another advantage of microfiber fabric (compared to leather) is that it can be coated with various finishes and can be treated with antibacterial chemicals. Fabric can also be printed with various designs, embroidered with colored thread, and heat-embossed.

Other uses

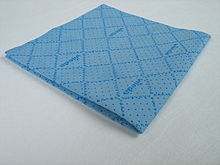

Textiles for cleaning

In cleaning products, microfiber can be 100% polyester, or a blend of polyester and polyamide (nylon). It can be either a woven product or a non woven product, the latter most often used in limited use or disposable cloths. In the highest-quality fabrics for cleaning applications, the fiber is split during the manufacturing process to produce multi-stranded fibers. A cross section of the split microfiber fabric under high magnification would look like an asterisk.

The split fibers and the size of the individual filaments make the cloths more effective than other fabrics for cleaning purposes. The structure traps and retains the dirt and also absorbs liquids. Unlike cotton, microfiber leaves no lint, the exception being some micro suede blends, where the surface is mechanically processed to produce a soft plush feel.

For microfiber to be most effective as a cleaning product, especially for water-soluble soils and waxes, it should be a split microfiber. Non-split microfiber is little more than a very soft cloth. The main exception is for cloths used for facial cleansing and for the removal of skin oils (sebum), sunscreens, and mosquito repellents from optical surfaces such as cameras, phones and eyeglasses wherein higher-end proprietary woven, 100% polyester cloths using 2 μm filaments, will absorb these types of oils without smearing.

Microfiber used in non-sports-related clothing, furniture, and other applications is not split because it is not designed to be absorbent, just soft. When buying, microfiber may not be labeled to designate whether it is split. One method to determine the type of microfiber is to run the cloth over the palm of the hand. A split microfiber will cling to imperfections of the skin and can be either heard or felt as it does. Alternatively, a small amount of water can be poured onto a hard, flat surface and pushed with the microfiber. If the water is pushed rather than absorbed, it is not split microfiber.

Microfiber can be electrostatically charged for special purposes like filtration.

Cloths and mops

Microfiber products used for consumer cleaning are generally constructed from split conjugated fibers of polyester and polyamide. Microfiber used for commercial cleaning products also includes many products constructed of 100% polyester. Microfiber products are able to absorb oils especially well and are not hard enough to scratch even paintwork unless they have retained grit or hard particles from previous use. Due to hydrogen bonding, microfiber cloth containing polyamide absorbs and holds more water than other types of fibres.

Microfiber is widely used by car detailers to handle tasks such as removing wax from paintwork, quick detailing, interior cleaning, glass cleaning, and drying. Because of their fine fibers which leave no lint or dust, microfiber towels are used by car detailers and enthusiasts in a similar manner to a chamois leather.

Microfiber is used in many professional cleaning applications, for example in mops and cleaning cloths. Although microfiber mops cost more than non-microfiber mops, they may be more economical because they last longer and require less effort to use.

Microfiber textiles designed for cleaning clean on a microscopic scale. According to tests, using microfiber materials to clean a surface reduces bacteria by 99%, whereas a conventional cleaning material reduces bacteria by only 33%. Microfiber cleaning tools also absorb fat and grease and their electrostatic properties allow them to attract dust strongly.

Microfiber cloths are also used to clean photographic lenses as they absorb oily matter without being abrasive or leaving a residue, and are sold by major manufacturers such as Sinar, ZEISS, Nikon and Canon. Small microfiber cleaning cloths are commonly sold for cleaning computer screens, cameras, phones and eyeglasses.

Microfiber is unsuitable for some cleaning applications as it accumulates dust, debris, and particles. Sensitive surfaces (such as all high-tech coated surfaces e.g. CRT, LCD and plasma screens) can easily be damaged by a microfiber cloth if it has picked up grit or other abrasive particles during use. One way to minimize the risk of damage to flat surfaces is to use a flat, non-rugged microfiber cloth, as these tend to be less prone to retaining grit.

Rags made of microfiber must only be washed with regular laundry detergent, not oily, self-softening, soap-based detergents. Fabric softener must not be used; the oils and cationic surfactants in the softener and self-softening detergents will clog up the fibers and make them less absorbent until the oils are washed out. Hot temperatures may also cause microfiber cloth to melt or become wrinkled.

Insulation

Microfiber materials such as PrimaLoft are used for thermal insulation as a replacement for down feather insulation in sleeping bags and outdoor equipment, because of their better retention of heat when damp or wet. Microfiber is also used for water insulation in automotive car covers. Depending on the technology the fiber manufacturer is using, such material may contain from 2 up to 5 thin layers, merged. Such combination ensures not only high absorption factor, but also breathability of the material, which prevents the greenhouse effect.

Basketballs

With microfiber-shelled basketballs already used by FIBA, the NBA introduced a microfiber ball for the 2006–07 season. The ball, which is manufactured by Spalding, does not require a "break-in" period of use as leather balls do and has the ability to absorb water and oils, meaning that sweat from players touching the ball is better absorbed, making the ball less slippery. Over the course of the season, the league received many complaints from players who found that the ball bounced differently from leather balls, and that it left cuts on their hands. On January 1, 2007, the league scrapped the use of all microfiber balls and returned to leather basketballs.

Other

Microfibers used in tablecloths, furniture, and car interiors are designed to repel wetting and consequently are difficult to stain. In furniture, microfiber is a close alternative to leather due to the simple upkeep of the qualities of the material. Easy to wipe off liquids and better suited for individuals with pets. Microfiber tablecloths will bead liquids until they are removed and are sometimes advertised showing red wine on a white tablecloth that wipes clean with a paper towel. This and the ability to mimic suede economically are common selling points for microfiber upholstery fabrics (e.g., for couches).

Microfibers are used in towels especially those to be used at swimming pools as even a small towel dries the body quickly. They dry quickly and are less prone than cotton towels to become stale if not dried immediately. Microfiber towels need to be soaked in water and pressed before use, as they would otherwise repel water as microfiber tablecloths do.

Microfiber is also used for other applications such as making menstrual pads, cloth diaper inserts, body scrubbers, face mitts, whiteboard cleaners, and various goods that need to absorb water and/or attract small particles.

In the medical world, the properties of microfibers are used in the coating of certain fabric sheets used to strengthen the original material.

Environmental and safety issues

Microfiber textiles tend to be flammable if manufactured from hydrocarbons (polyester) or carbohydrates (cellulose) and emit toxic gases when burning, more so if aromatic (PET, PS, ABS) or treated with halogenated flame retardants and azo dyes. Their polyester and nylon stock are made from petrochemicals, which are not a renewable resource and are not biodegradable.

For most cleaning applications they are designed for repeated use rather than being discarded after use. An exception to this is the precise cleaning of optical components where a wet cloth is drawn once across the object and must not be used again as the debris collected are now embedded in the cloth and may scratch the optical surface.

Microfiber products also enter the oceanic water supply and food chain similarly to other microplastics. Synthetic clothing made of microfibers that are washed release materials and travel to local wastewater treatment plants, contributing to plastic pollution in water. A study by the clothing brand Patagonia and University of California, Santa Barbara, found that when synthetic jackets made of microfibers are washed, on average 1.7 grams (0.060 oz) of microfibers are released from the washing machine. These microfibers then travel to local wastewater treatment plants, where up to 40% of them enter into rivers, lakes, and oceans where they contribute to the overall plastic pollution. Microfibers account for 85% of man-made debris found on shorelines worldwide. Fibers retained in wastewater treatment sludge (biosolids) that are land-applied can persist in soils.

See also

References

- Nakajima T, Kajiwara K, McIntyre J E, 1994. Advanced Fiber Spinning Technology Archived 2020-01-26 at the Wayback Machine. Woodhead Publishing, pp. 187–188

- Kanigel, Robert, 2007. Faux Real: Genuine Leather and 200 Years of Inspired Fakes Archived 2018-10-11 at the Wayback Machine. Joseph Henry Press, pp. 186–192

- "SYNTHETIC SPLIT MICROFIBER TECHNOLOGY FOR FILTRATION " by Jeff Dugan, Vice President Research and Development Fiber Innovation Technologies and Ed Homonoff President Edward C. Homonoff & Associates, LLC

- UC Davis Health System: Newroom. UC Davis Pioneers Use of Microfiber Mops in Hospitals: Mops reduce injuries, kill more germs and reduce costs. Archived 2010-07-06 at the Wayback Machine June 23, 2006.

- Sustainable Hospitals Project, University of Massachusetts Lowell. 10 Reasons to Use Microfiber Mopping. Archived 2007-04-10 at the Wayback Machine

- UC Davis Health System: Newroom UC Davis Pioneers Use Of Microfiber Mops In Hospitals. Ucdmc.ucdavis.edu. Retrieved on 2010-12-01.

- ^ "Discover Microfiber Clothes and Linens and How to Use and Wash Them". The Spruce.

- ^ NBA Introduces New Game Ball Archived 2012-03-17 at the Wayback Machine. NBA.com, June 28, 2006.

- ^ Josh Hart, NBA to Take Microfiber Basketball and Go Home Archived 2008-12-12 at the Wayback Machine. National Ledger, December 12, 2006.

- Mukhopadhyay, Samrat (September 2002). "Microfibres—An overview". Indian Journal of Fibre and Textile Research. 27: 312. ISSN 0975-1025. Retrieved October 20, 2023 – via NIScPR.

- Braun, Emil; Levin, Barbara C. (1986). "Polyesters: A Review of the Literature on Products of Combustion and Toxicity" (PDF). Fire and Materials. 10 (3–4): 107–123. doi:10.1002/fam.810100304. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 30, 2010. Retrieved December 2, 2012.

- Barbara Flanagan, The Case of the Missing Microfiber. I.D., April 22, 2008.

- ^ Browne, Mark Anthony; Crump, Phillip; Niven, Stewart J.; Teuten, Emma; Tonkin, Andrew; Galloway, Tamara; Thompson, Richard (2011). "Accumulation of microplastic on shorelines worldwide: Sources and sinks". Environmental Science & Technology. 45 (21): 9175–9179. doi:10.1021/es201811s. PMID 21894925. S2CID 19178027.

- "Project Findings". Microfiber Pollution & the apparel industry. Archived from the original on March 26, 2017. Retrieved March 25, 2017.

- O'Connor, Mary Catherine (June 20, 2016). "Patagonia's New Study Finds Fleece Jackets Are a Serious Pollutant". Outside Online. Archived from the original on March 26, 2017. Retrieved March 25, 2017.

- Paddison, Laura (September 26, 2016). "Single clothes wash may release 700,000 microplastic fibres, study finds". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on February 10, 2020. Retrieved June 15, 2017.

- Zubris, Kimberly Ann V.; Richards, Brian K. (November 2005). "Synthetic fibers as an indicator of land application of sludge". Environmental Pollution. 138 (2): 201–211. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2005.04.013. PMID 15967553.

| Fibers | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Natural |

| ||||||||

| Synthetic |

| ||||||||