Medical condition

| Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis | |

|---|---|

| Other names |

|

| |

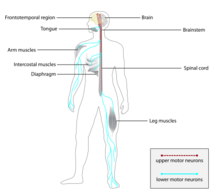

| Parts of the nervous system affected by ALS, causing progressive symptoms in skeletal muscles throughout the body | |

| Specialty | Neurology |

| Symptoms | Early: Stiff muscles, muscle twitches, gradual increasing weakness Later: Difficulty in speaking, swallowing, and breathing; respiratory failure; 10–15% experience frontotemporal dementia |

| Complications | Falling (accident); Respiratory failure; Pneumonia; Malnutrition |

| Usual onset | 45–75 years |

| Causes | Unknown (about 85%), genetic (about 15%) |

| Risk factors | Genetic risk factors; age; male sex; heavy metals; organic chemicals; smoking; electric shock; physical exercise; head injury |

| Diagnostic method | Clinical diagnosis of exclusion based on progressive symptoms of upper and lower motor neuron degeneration in which no other explanation can be found. Supportive evidence from electromyography, genetic testing, and neuroimaging |

| Differential diagnosis | Multifocal motor neuropathy, Kennedy's disease, Hereditary spastic paraplegia, Nerve compression syndrome, Diabetic neuropathy, Post-polio syndrome, Myasthenia gravis, Multiple sclerosis |

| Treatment | Walker (mobility); Wheelchair; Non-invasive ventilation; Feeding tubes; Augmentative and alternative communication; symptomatic management |

| Medication | Riluzole, Edaravone, Sodium phenylbutyrate/ursodoxicoltaurine, Tofersen, Dextromethorphan/quinidine |

| Prognosis | Life expectancy highly variable but typically 2–4 years after diagnosis |

| Frequency |

|

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), also known as motor neurone disease (MND) or (in the United States) Lou Gehrig's disease (LGD), is a rare, terminal neurodegenerative disorder that results in the progressive loss of both upper and lower motor neurons that normally control voluntary muscle contraction. ALS is the most common form of the motor neuron diseases. ALS often presents in its early stages with gradual muscle stiffness, twitches, weakness, and wasting. Motor neuron loss typically continues until the abilities to eat, speak, move, and, lastly, breathe are all lost. While only 15% of people with ALS also fully develop frontotemporal dementia, an estimated 50% face at least some minor difficulties with thinking and behavior. Depending on which of the aforementioned symptoms develops first, ALS is classified as limb-onset (begins with weakness in the arms or legs) or bulbar-onset (begins with difficulty in speaking or swallowing).

Most cases of ALS (about 90–95%) have no known cause, and are known as sporadic ALS. However, both genetic and environmental factors are believed to be involved. The remaining 5–10% of cases have a genetic cause, often linked to a family history of the disease, and these are known as familial ALS (hereditary). About half of these genetic cases are due to disease-causing variants in one of four specific genes. The diagnosis is based on a person's signs and symptoms, with testing conducted to rule out other potential causes.

There is no known cure for ALS. The goal of treatment is to slow the disease progression, and improve symptoms. FDA-approved treatments that slow the progression of ALS include riluzole and edaravone. Non-invasive ventilation may result in both improved quality and length of life. Mechanical ventilation can prolong survival but does not stop disease progression. A feeding tube may help maintain weight and nutrition. Death is usually caused by respiratory failure. The disease can affect people of any age, but usually starts around the age of 60. The average survival from onset to death is two to four years, though this can vary, and about 10% of those affected survive longer than ten years.

Descriptions of the disease date back to at least 1824 by Charles Bell. In 1869, the connection between the symptoms and the underlying neurological problems was first described by French neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot, who in 1874 began using the term amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.

Classification

ALS is a motor neuron disease, which is a group of neurological disorders that selectively affect motor neurons, the cells that control voluntary muscles of the body. Other motor neuron diseases include primary lateral sclerosis (PLS), progressive muscular atrophy (PMA), progressive bulbar palsy, pseudobulbar palsy, and monomelic amyotrophy (MMA).

As a disease, ALS itself can be classified in a few different ways: by which part of the motor neurons are affected; by the parts of the body first affected; whether it is genetic; and by the age at which it started. Each individual diagnosed with the condition will sit at a unique place at the intersection of these complex and overlapping subtypes, which presents a challenge to diagnosis, understanding, and prognosis.

Subtypes of motor neuron disease

ALS can be classified by the types of motor neurons that are affected. To successfully control any voluntary muscle in the body, a signal must be sent from the motor cortex in the brain down the upper motor neuron as it travels down the spinal cord. There, it connects via a synapse to the lower motor neuron which connects to the muscle itself. Damage to either the upper or lower motor neuron, as it makes its way from the brain to muscle, causes different types of symptoms. Damage to the upper motor neuron typically causes spasticity including stiffness and increased tendon reflexes, and/or clonus, while damage to the lower motor neuron typically causes weakness, muscle atrophy, and fasciculations.

Classical, or classic ALS, involves degeneration to both the upper motor neurons in the brain and the lower motor neurons in the spinal cord. Primary lateral sclerosis (PLS) involves degeneration of only the upper motor neurons, and progressive muscular atrophy (PMA) involves only the lower motor neurons. There is debate over whether PLS and PMA are separate diseases or simply variants of ALS.

| Main ALS subtypes | Upper motor neuron degeneration | Lower motor neuron degeneration |

|---|---|---|

| Classical ALS | Yes | Yes |

| Primary lateral sclerosis (PLS) | Yes | No |

| Progressive muscular atrophy (PMA) | No | Yes |

Classical ALS accounts for about 70% of all cases of ALS and can be subdivided into where symptoms first appear as these are usually focussed to one region of the body at initial presentation before later spread. Limb-onset ALS (also known as spinal-onset) and bulbar-onset ALS. Limb-onset ALS begins with weakness in the hands, arms, feet, and/or legs and accounts for about two-thirds of all classical ALS cases. Bulbar-onset ALS begins with weakness in the muscles of speech, chewing, and swallowing and accounts for about 25% of classical ALS cases. A rarer type of classical ALS affecting around 3% of patients is respiratory-onset, in which the initial symptoms are difficulty breathing (dyspnea) upon exertion, at rest, or while lying flat (orthopnea).

Primary lateral sclerosis (PLS) is a subtype of the overall ALS category which accounts for about 5% of all cases and only affects the upper motor neurons in the arms, legs, and bulbar region. However, more than 75% of people with apparent PLS go on to later develop lower motor neuron signs within four years of symptom onset, meaning that a definitive diagnosis of PLS cannot be made until several years have passed. PLS has a better prognosis than classical ALS, as it progresses slower, results in less functional decline, does not affect the ability to breathe, and causes less severe weight loss than classical ALS.

Progressive muscular atrophy (PMA) is another subtype that accounts for about 5% of the overall ALS category and affects lower motor neurons in the arms, legs, and bulbar region. While PMA is associated with longer survival on average than classical ALS, it is still progressive over time, eventually leading to respiratory failure and death. As with PLS developing into classical ALS, PMA can also develop into classical ALS over time if the lower motor neuron involvement progresses to include upper motor neurons, in which case the diagnosis might be changed to classic ALS.

Rare isolated variants of ALS

Isolated variants of ALS have symptoms that are limited to a single region for at least a year; they progress more slowly than classical ALS and are associated with longer survival. These regional variants of ALS can only be considered as a diagnosis should the initial symptoms fail to spread to other spinal cord regions for an extended period of time (at least 12 months). Flail arm syndrome is characterized by lower motor neuron damage affecting the arm muscles, typically starting with the upper arms symmetrically and progressing downwards to the hands. Flail leg syndrome is characterized by lower motor neuron damage leading to asymmetrical weakness and wasting in the legs starting around the feet. Isolated bulbar palsy is characterized by upper or lower motor neuron damage in the bulbar region (in the absence of limb symptoms for at least 20 months), leading to gradual onset of difficulty with speech (dysarthria) and swallowing (dysphagia).

Age of onset

ALS can also be classified based on the age of onset. While the peak age of onset is 58 to 63 for sporadic ALS and 47 to 52 for genetic ALS, about 10% of all cases of ALS begin before age 45 ("young-onset" ALS), and about 1% of all cases begin before age 25 ("juvenile" ALS). People who develop young-onset ALS are more likely to be male, less likely to have bulbar onset of symptoms, and more likely to have a slower progression of the disease. Juvenile ALS is more likely to be genetic in origin than adult-onset ALS; the most common genes associated with juvenile ALS are FUS, ALS2, and SETX. Although most people with juvenile ALS live longer than those with adult-onset ALS, some of them have specific mutations in FUS and SOD1 that are associated with a poor prognosis. Late onset (after age 65) is generally associated with a more rapid functional decline and shorter survival.

Signs and symptoms

The disorder causes muscle weakness, atrophy, and muscle spasms throughout the body due to the degeneration of the upper motor and lower motor neurons. Sensory nerves and the autonomic nervous system are generally unaffected, meaning the majority of people with ALS maintain hearing, sight, touch, smell, and taste.

Initial symptoms

The start of ALS may be so subtle that the symptoms are overlooked. The earliest symptoms of ALS are muscle weakness or muscle atrophy, typically on one side of the body. Other presenting symptoms include trouble swallowing or breathing, cramping, or stiffness of affected muscles; muscle weakness affecting an arm or a leg; or slurred and nasal speech. The parts of the body affected by early symptoms of ALS depend on which motor neurons in the body are damaged first.

In limb-onset ALS, the first symptoms are in the arms or the legs. If the legs are affected first, people may experience awkwardness, tripping, or stumbling when walking or running; this is often marked by walking with a "dropped foot" that drags gently on the ground. If the arms are affected first, they may experience difficulty with tasks requiring manual dexterity, such as buttoning a shirt, writing, or turning a key in a lock.

In bulbar-onset ALS, the first symptoms are difficulty speaking or swallowing. Speech may become slurred, nasal in character, or quieter. There may be difficulty with swallowing and loss of tongue mobility. A smaller proportion of people experience "respiratory-onset" ALS, where the intercostal muscles that support breathing are affected first.

Over time, people experience increasing difficulty moving, swallowing (dysphagia), and speaking or forming words (dysarthria). Symptoms of upper motor neuron involvement include tight and stiff muscles (spasticity) and exaggerated reflexes (hyperreflexia), including an overactive gag reflex. While the disease does not cause pain directly, pain is a symptom experienced by most people with ALS caused by reduced mobility. Symptoms of lower motor neuron degeneration include muscle weakness and atrophy, muscle cramps, and fleeting twitches of muscles that can be seen under the skin (fasciculations).

Progression

Although the initial site of symptoms and subsequent rate of disability progression vary from person to person, the initially affected body region is usually the most affected over time, and symptoms usually spread to a neighbouring body region. For example, symptoms starting in one arm usually spread next to either the opposite arm or to the leg on the same side. Bulbar-onset patients most typically get their next symptoms in their arms rather than legs, arm-onset patients typically spread to the legs before the bulbar region, and leg-onset patients typically spread to the arms rather than the bulbar region. Over time, regardless of where symptoms began, most people eventually lose the ability to walk or use their hands and arms independently. Less consistently, they may lose the ability to speak and to swallow food. It is the eventual development of weakness of the respiratory muscles, with the loss of ability to cough and to breathe without support, that is ultimately life-shortening in ALS.

The rate of progression can be measured using the ALS Functional Rating Scale - Revised (ALSFRS-R), a 12-item instrument survey administered as a clinical interview or self-reported questionnaire that produces a score between 48 (normal function) and 0 (severe disability). The ALSFRS-R is the most frequently used outcome measure in clinical trials and is used by doctors to track disease progression. Though the degree of variability is high and a small percentage of people have a much slower progression, on average people with ALS lose about 1 ALSFRS-R point per month. Brief periods of stabilization ("plateaus") and even small reversals in ALSFRS-R score are not uncommon, due to the fact the tool is subjective, can be affected by medication, and different forms of compensation for changes in function. However, it is rare (<1%) for these improvements to be large (i.e. greater than 4 ALSFRS-R points) or sustained (i.e. greater than 12 months). A survey-based study among clinicians showed that they rated a 20% change in the slope of the ALSFRS-R as being clinically meaningful, which is the most common threshold used to determine whether a new treatment is working in clinical trials.

Late-stage disease management

Difficulties with chewing and swallowing make eating very difficult (dysphagia) and increase the risk of choking or of aspirating food into the lungs. In later stages of the disorder, aspiration pneumonia can develop, and maintaining a healthy weight can become a significant problem that may require the insertion of a feeding tube. As the diaphragm and intercostal muscles of the rib cage that support breathing weaken, measures of lung function such as vital capacity and inspiratory pressure diminish. In respiratory-onset ALS, this may occur before significant limb weakness is apparent. Individuals affected by the disorder may ultimately lose the ability to initiate and control all voluntary movement, known as locked-in syndrome. Bladder and bowel function are usually spared, meaning urinary and fecal incontinence are uncommon, although trouble getting to a toilet can lead to difficulties. The extraocular muscles responsible for eye movement are usually spared, meaning the use of eye tracking technology to support augmentative communication is often feasible, albeit slow, and needs may change over time. Despite these challenges, many people in an advanced state of disease report satisfactory wellbeing and quality of life.

Prognosis, staging, and survival

Although respiratory support using non-invasive ventilation can ease problems with breathing and prolong survival, it does not affect the progression rate of ALS. Most people with ALS die between two and four years after the diagnosis. Around 50% of people with ALS die within 30 months of their symptoms beginning, about 20% live between five and ten years, and about 10% survive for 10 years or longer.

The most common cause of death among people with ALS is respiratory failure, often accelerated by pneumonia. Most ALS patients die at home after a period of worsening difficulty breathing, a decline in their nutritional status, or a rapid worsening of symptoms. Sudden death or acute respiratory distress are uncommon. Access to palliative care is recommended from an early stage to explore options, ensure psychosocial support for the patient and caregivers, and to discuss advance healthcare directives.

As with cancer staging, ALS has staging systems numbered between 1 and 4 that are used for research purposes in clinical trials. Two very similar staging systems emerged around a similar time, the King's staging system and Milano-Torino (MiToS) functional staging.

| Stage 1 | Stage 2 | Stage 3 | Stage 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stage description | Symptom onset, involvement of the first region | 2A: Diagnosis

2B: Involvement of the second region |

Involvement of the third region | 4A: Need for a feeding tube

4B: Need for non-invasive ventilation |

| Median time to stage | 13.5 months | 17.7 months | 23.3 months | 4A: 17.7 months

4B: 30.3 months |

| Stage 0 | Stage 1 | Stage 2 | Stage 3 | Stage 4 | Stage 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stage description | No loss of a functional domain | Loss of 1 domain | Loss of 2 domains | Loss of 3 domains | Loss of 4 domains | Death |

| Probability of death at each stage | 7% | 26% | 33% | 33% | 86% |

Providing individual patients with a precise prognosis is not currently possible, though research is underway to provide statistical models on the basis of prognostic factors including age at onset, progression rate, site of onset, and presence of frontotemporal dementia. Those with a bulbar onset have a worse prognosis than limb-onset ALS; a population-based study found that bulbar-onset ALS patients had a median survival of 2.0 years and a 10-year survival rate of 3%, while limb-onset ALS patients had a median survival of 2.6 years and a 10-year survival rate of 13%. Those with respiratory-onset ALS had a shorter median survival of 1.4 years and 0% survival at 10 years. While astrophysicist Stephen Hawking lived for 55 more years following his diagnosis, his was an unusual case.

Cognitive, emotional, and behavioral symptoms

Cognitive impairment or behavioral dysfunction is present in 30–50% of individuals with ALS, and can appear more frequently in later stages of the disease. Language dysfunction, executive dysfunction, and troubles with social cognition and verbal memory are the most commonly reported cognitive symptoms in ALS. Cognitive impairment is found more frequently in patients with C9orf72 gene repeat expansions, bulbar onset, bulbar symptoms, family history of ALS, and/or a predominantly upper motor neuron phenotype.

Emotional lability is a symptom in which patients cry, smile, yawn, or laugh, either in the absence of emotional stimuli, or when they are feeling the opposite emotion to that being expressed; it is experienced by about half of ALS patients and is more common in those with bulbar-onset ALS. While relatively benign relative to other symptoms, it can cause increased stigma and social isolation as people around the patient struggle to react appropriately to what can be frequent and inappropriate outbursts in public.

In addition to mild changes in cognition that may only emerge during neuropsychological testing, around 10–15% of individuals have signs of frontotemporal dementia (FTD). Repeating phrases or gestures, apathy, and loss of inhibition are the most frequently reported behavioral features of ALS. ALS and FTD are now considered to be part of a common disease spectrum (ALS–FTD) because of genetic, clinical, and pathological similarities. Genetically, repeat expansions in the C9orf72 gene account for about 40% of genetic ALS and 25% of genetic FTD.

Cognitive and behavioral issues are associated with a poorer prognosis as they may reduce adherence to medical advice, and deficits in empathy and social cognition which may increase caregiver burden.

Cause

It is not known what causes sporadic ALS, hence it is described as an idiopathic disease. Though its exact cause is unknown, genetic and environmental factors are thought to be of roughly equal importance. The genetic factors are better understood than the environmental factors; no specific environmental factor has been definitively shown to cause ALS. A multi-step liability threshold model for ALS proposes that cellular damage accumulates over time due to genetic factors present at birth and exposure to environmental risks throughout life. ALS can strike at any age, but its likelihood increases with age. Most people who develop ALS are between the ages of 40 and 70, with an average age of 55 at the time of diagnosis. ALS is 20% more common in men than women, but this difference in sex distribution is no longer present in patients with onset after age 70.

Genetics and genetic testing

Main article: Genetics of amyotrophic lateral sclerosisWhile they appear identical clinically and pathologically, ALS can be classified as being either familial or sporadic, depending on whether there is a known family history of the disease and/or whether an ALS-associated genetic mutation has been identified via genetic testing. Familial ALS is thought to account for 10–15% of cases overall and can include monogenic, oligogenic, and polygenic modes of inheritance.

There is considerable variation among clinicians on how to approach genetic testing in ALS, and only about half discuss the possibility of genetic inheritance with their patients, particularly if there is no discernible family history of the disease. In the past, genetic counseling and testing was only offered to those with obviously familial ALS. But it is increasingly recognized that cases of sporadic ALS may also be due to disease-causing de novo mutations in SOD1, or C9orf72, an incomplete family history, or incomplete penetrance, meaning that a patient's ancestors carried the gene but did not express the disease in their lifetimes. The lack of positive family history may be caused by lack of historical records, having a smaller family, older generations dying earlier of causes other than ALS, genetic non-paternity, and uncertainty over whether certain neuropsychiatric conditions (e.g. frontotemporal dementia, other forms of dementia, suicide, psychosis, schizophrenia) should be considered significant when determining a family history. There have been calls in the research community to routinely counsel and test all diagnosed ALS patients for familial ALS, particularly as there is now a licensed gene therapy (tofersen) specifically targeted to carriers of SOD-1 ALS. A shortage of genetic counselors and limited clinical capacity to see such at-risk individuals makes this challenging in practice, as does the unequal access to genetic testing around the world.

More than 40 genes have been associated with ALS, of which four account for nearly half of familial cases, and around 5% of sporadic cases: C9orf72 (40% of familial cases, 7% sporadic), SOD1 (12% of familial cases, 1–2% sporadic), FUS (4% of familial cases, 1% sporadic), and TARDBP (4% of familial cases, 1% sporadic), with the remaining genes mostly accounting for fewer than 1% of either familial or sporadic cases. ALS genes identified to date explain the cause of about 70% of familial ALS and about 15% of sporadic ALS. Overall, first-degree relatives of an individual with ALS have a ~1% risk of developing ALS themselves.

Environmental and other factors

The multi-step hypothesis suggests the disease is caused by some interaction between an individual's genetic risk factors and their cumulative lifetime of exposures to environmental factors, termed their exposome. The most consistent lifetime exposures associated with developing ALS (other than genetic mutations) include heavy metals (e.g. lead and mercury), chemicals (e.g. pesticides and solvents), electric shock, physical injury (including head injury), and smoking (in men more than women). Overall these effects are small, with each exposure in isolation only increasing the likelihood of a very rare condition by a small amount. For instance, an individual's lifetime risk of developing ALS might go from "1 in 400" without exposure to between "1 in 300" and "1 in 200" if they were exposed to heavy metals.

Some occupations are heavily dependent upon using these known environmental risk factors. People who have worked more than 10 years in agriculture with exposure to thinners, paint removers, electromagnetic fields, fungicides, and specific metals have shown a 2.7-fold increased risk of developing ALS (Filippini et al, 2020). A range of other factors have weaker evidence supporting them and include participation in professional sports, having a lower body mass index, lower educational attainment, manual occupations, military service, exposure to Beta-N-methylamino-L-alanin (BMAA), and viral infections.

Although some personality traits, such as openness, agreeableness and conscientiousness appear remarkably common among patients with ALS, it remains open whether personality can increase susceptibility to ALS directly. Instead, genetic factors giving rise to personality might simultaneously predispose people to develop ALS, or the above personality traits might underlie lifestyle choices which are in turn risk factors for ALS.

Pathophysiology

Neuropathology

Upon examination at autopsy, features of the disease that can be seen with the naked eye include skeletal muscle atrophy, motor cortex atrophy, sclerosis of the corticospinal and corticobulbar tracts, thinning of the hypoglossal nerves (which control the tongue), and thinning of the anterior roots of the spinal cord.

The defining feature of ALS is the death of both upper motor neurons (located in the motor cortex of the brain) and lower motor neurons (located in the brainstem and spinal cord). In ALS with frontotemporal dementia, neurons throughout the frontal and temporal lobes of the brain die as well. The pathological hallmark of ALS is the presence of inclusion bodies (abnormal aggregations of protein) known as Bunina bodies in the cytoplasm of motor neurons. In about 97% of people with ALS, the main component of the inclusion bodies is TDP-43 protein; however, in those with SOD1 or FUS mutations, the main component of the inclusion bodies is SOD1 protein or FUS protein, respectively. Prion-like propagation of misfolded proteins from cell to cell may explain why ALS starts in one area and spreads to others. The glymphatic system may also be involved in the pathogenesis of ALS.

Biochemistry

It is still not fully understood why neurons die in ALS, but this neurodegeneration is thought to involve many different cellular and molecular processes. The genes known to be involved in ALS can be grouped into three general categories based on their normal function: protein degradation, the cytoskeleton, and RNA processing. Mutant SOD1 protein forms intracellular aggregations that inhibit protein degradation. Cytoplasmic aggregations of wild-type (normal) SOD1 protein are common in sporadic ALS. It is thought that misfolded mutant SOD1 can cause misfolding and aggregation of wild-type SOD1 in neighboring neurons in a prion-like manner. Other protein degradation genes that can cause ALS when mutated include VCP, OPTN, TBK1, and SQSTM1. Three genes implicated in ALS that are important for maintaining the cytoskeleton and for axonal transport include DCTN1, PFN1, and TUBA4A.

Several ALS genes encode RNA-binding proteins. The first to be discovered was TDP-43 protein, a nuclear protein that aggregates in the cytoplasm of motor neurons in almost all cases of ALS; however, mutations in TARDBP, the gene that codes for TDP-43, are a rare cause of ALS. FUS codes for FUS, another RNA-binding protein with a similar function to TDP-43, which can cause ALS when mutated. It is thought that mutations in TARDBP and FUS increase the binding affinity of the low-complexity domain, causing their respective proteins to aggregate in the cytoplasm. Once these mutant RNA-binding proteins are misfolded and aggregated, they may be able to misfold normal proteins both within and between cells in a prion-like manner. This also leads to decreased levels of RNA-binding protein in the nucleus, which may mean that their target RNA transcripts do not undergo normal processing. Other RNA metabolism genes associated with ALS include ANG, SETX, and MATR3.

C9orf72 is the most commonly mutated gene in ALS and causes motor neuron death through a number of mechanisms. The pathogenic mutation is a hexanucleotide repeat expansion (a series of six nucleotides repeated over and over); people with up to 30 repeats are considered normal, while people with hundreds or thousands of repeats can have familial ALS, frontotemporal dementia, or sometimes sporadic ALS. The three mechanisms of disease associated with these C9orf72 repeats are deposition of RNA transcripts in the nucleus, translation of the RNA into toxic dipeptide repeat proteins in the cytoplasm, and decreased levels of the normal C9orf72 protein. Mitochondrial bioenergetic dysfunction leading to dysfunctional motor neuron axonal homeostasis (reduced axonal length and fast axonal transport of mitochondrial cargo) has been shown to occur in C9orf72-ALS using human induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) technologies coupled with CRISPR/Cas9 gene-editing, and human post-mortem spinal cord tissue examination.

Excitotoxicity, or nerve cell death caused by high levels of intracellular calcium due to excessive stimulation by the excitatory neurotransmitter glutamate, is a mechanism thought to be common to all forms of ALS. Motor neurons are more sensitive to excitotoxicity than other types of neurons because they have a lower calcium-buffering capacity and a type of glutamate receptor (the AMPA receptor) that is more permeable to calcium. In ALS, there are decreased levels of excitatory amino acid transporter 2 (EAAT2), which is the main transporter that removes glutamate from the synapse; this leads to increased synaptic glutamate levels and excitotoxicity. Riluzole, a drug that modestly prolongs survival in ALS, inhibits glutamate release from pre-synaptic neurons; however, it is unclear if this mechanism is responsible for its therapeutic effect.

Diagnosis

No single test can provide a definite diagnosis of ALS. Instead, the diagnosis of ALS is primarily made based on a physician's clinical assessment after ruling out other diseases. Physicians often obtain the person's full medical history and conduct neurologic examinations at regular intervals to assess whether signs and symptoms such as muscle weakness, muscle atrophy, hyperreflexia, Babinski's sign, and spasticity are worsening. Many biomarkers are being studied for the condition, but as of 2023 are not in general medical use.

Differential diagnosis

Because symptoms of ALS can be similar to those of a wide variety of other, more treatable diseases or disorders, appropriate tests must be conducted to exclude the possibility of other conditions. One of these tests is electromyography (EMG), a special recording technique that detects electrical activity in muscles. Certain EMG findings can support the diagnosis of ALS. Another common test measures nerve conduction velocity (NCV). Specific abnormalities in the NCV results may suggest, for example, that the person has a form of peripheral neuropathy (damage to peripheral nerves) or myopathy (muscle disease) rather than ALS. While a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is often normal in people with early-stage ALS, it can reveal evidence of other problems that may be causing the symptoms, such as a spinal cord tumor, multiple sclerosis, a herniated disc in the neck, syringomyelia, or cervical spondylosis.

Based on the person's symptoms and findings from the examination and from these tests, the physician may order tests on blood and urine samples to eliminate the possibility of other diseases, as well as routine laboratory tests. In some cases, for example, if a physician suspects the person may have a myopathy rather than ALS, a muscle biopsy may be performed.

A number of infectious diseases can sometimes cause ALS-like symptoms, including human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), human T-lymphotropic virus (HTLV), Lyme disease, and syphilis. Neurological disorders such as multiple sclerosis, post-polio syndrome, multifocal motor neuropathy, CIDP, spinal muscular atrophy, and spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy can also mimic certain aspects of the disease and should be considered.

ALS must be differentiated from the "ALS mimic syndromes", which are unrelated disorders that may have a similar presentation and clinical features to ALS or its variants. Because the prognosis of ALS and closely related subtypes of motor neuron disease are generally poor, neurologists may carry out investigations to evaluate and exclude other diagnostic possibilities. Disorders of the neuromuscular junction, such as myasthenia gravis (MG) and Lambert–Eaton myasthenic syndrome, may also mimic ALS, although this rarely presents diagnostic difficulty over time. Benign fasciculation syndrome and cramp fasciculation syndrome may also, occasionally, mimic some of the early symptoms of ALS. Nonetheless, the absence of other neurological features that develop inexorably with ALS means that, over time, the distinction will not present any difficulty to the experienced neurologist; where doubt remains, EMG may be helpful.

Management

There is no cure for ALS. Management focuses on treating symptoms and providing supportive care, to improve quality of life and prolong survival. This care is best provided by multidisciplinary teams of healthcare professionals; attending a multidisciplinary ALS clinic is associated with longer survival, fewer hospitalizations, and improved quality of life.

Non-invasive ventilation (NIV) is the main treatment for respiratory failure in ALS. In people with normal bulbar function, it prolongs survival by about seven months and improves the quality of life. One study found that NIV is ineffective for people with poor bulbar function while another suggested that it may provide a modest survival benefit. Many people with ALS have difficulty tolerating NIV. Invasive ventilation is an option for people with advanced ALS when NIV is not enough to manage their symptoms. While invasive ventilation prolongs survival, disease progression, and functional decline continue. It may decrease the quality of life of people with ALS or their caregivers. Invasive ventilation is more commonly used in Japan than in North America or Europe.

Physical therapy can promote functional independence through aerobic, range of motion, and stretching exercises. Occupational therapy can assist with activities of daily living through adaptive equipment. Speech therapy can assist people with ALS who have difficulty speaking. Preventing weight loss and malnutrition in people with ALS improves both survival and quality of life. Initially, difficulty swallowing (dysphagia) can be managed by dietary changes and swallowing techniques. A feeding tube should be considered if someone with ALS loses 5% or more of their body weight or if they cannot safely swallow food and water. The feeding tube is usually inserted by percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG). There is weak evidence that PEG tubes improve survival. PEG insertion is usually performed with the intent of improving quality of life.

Palliative care should begin shortly after someone is diagnosed with ALS. Discussion of end-of-life issues gives people with ALS time to reflect on their preferences for end-of-life care and can help avoid unwanted interventions or procedures. Hospice care can improve symptom management at the end of life and increase the likelihood of a peaceful death. In the final days of life, opioids can be used to treat pain and dyspnea, while benzodiazepines can be used to treat anxiety.

Medications

Disease-slowing treatments

Riluzole has been found to modestly prolong survival by about 2–3 months. It may have a greater survival benefit for those with bulbar-onset ALS. It may work by decreasing release of the excitatory neurotransmitter glutamate from pre-synaptic neurons. The most common side effects are nausea and a lack of energy (asthenia). People with ALS should begin treatment with riluzole as soon as possible following their diagnosis. Riluzole is available as a tablet, liquid, or dissolvable oral film.

Edaravone has been shown to modestly slow the decline in function in a small group of people with early-stage ALS. It may work by protecting motor neurons from oxidative stress. The most common side effects are bruising and gait disturbance. Edaravone is available as an intravenous infusion or as an oral suspension.

AMX0035 (Relyvrio) is a combination of sodium phenylbutyrate and taurursodiol, which was initially shown to prolong the survival of patients by an average of six months. Relyvrio was withdrawn by the manufacturer in April 2024 following the completion of the Phase 3 PHOENIX trial which did not show substantial benefit to ALS patients.

Tofersen (Qalsody) is an antisense oligonucleotide that was approved for medical use in the United States in April 2023, for the treatment of SOD1-associated ALS. In a study of 108 patients with SOD1-associated ALS there was a non-significant trend towards a slowing of progression, as well as a significant reduction in neurofilament light chain, a putative ALS biomarker thought to indicate neuronal damage. A follow-up study and open-label extension suggested that earlier treatment initiation had a beneficial effect on slowing disease progression. Tofersen is available as an intrathecal injection into the lumbar cistern at the base of the spine.

Symptomatic treatments

Other medications may be used to help reduce fatigue, ease muscle cramps, control spasticity, and reduce excess saliva and phlegm. Gabapentin, pregabalin, and tricyclic antidepressants (e.g., amitriptyline) can be used for neuropathic pain, while nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), acetaminophen, and opioids can be used for nociceptive pain.

Depression can be treated with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) or tricyclic antidepressants, while benzodiazepines can be used for anxiety. There are no medications to treat cognitive impairment/frontotemporal dementia (FTD); however, SSRIs and antipsychotics can help treat some of the symptoms of FTD. Baclofen and tizanidine are the most commonly used oral drugs for treating spasticity; an intrathecal baclofen pump can be used for severe spasticity. Atropine, scopolamine, amitriptyline, or glycopyrrolate may be prescribed when people with ALS begin having trouble swallowing their saliva (sialorrhea).

A 2017 review concluded that mexiletine is safe and effective for treating cramps in ALS based on a randomized controlled trial from 2016.

Breathing support

Non-invasive ventilation

Non-invasive ventilation (NIV) is the primary treatment for respiratory failure in ALS and was the first treatment shown to improve both survival and quality of life. NIV uses a face or nasal mask connected to a ventilator that provides intermittent positive pressure to support breathing. Continuous positive pressure is not recommended for people with ALS because it makes breathing more difficult. Initially, NIV is used only at night because the first sign of respiratory failure is decreased gas exchange (hypoventilation) during sleep; symptoms associated with this nocturnal hypoventilation include interrupted sleep, anxiety, morning headaches, and daytime fatigue. As the disease progresses, people with ALS develop shortness of breath when lying down, during physical activity or talking, and eventually at rest. Other symptoms include poor concentration, poor memory, confusion, respiratory tract infections, and a weak cough. Respiratory failure is the most common cause of death in ALS.

It is important to monitor the respiratory function of people with ALS every three months because beginning NIV soon after the start of respiratory symptoms is associated with increased survival. This involves asking the person with ALS if they have any respiratory symptoms and measuring their respiratory function. The most commonly used measurement is upright forced vital capacity (FVC), but it is a poor detector of early respiratory failure and is not a good choice for those with bulbar symptoms, as they have difficulty maintaining a tight seal around the mouthpiece. Measuring FVC while the person is lying on their back (supine FVC) is a more accurate measure of diaphragm weakness than upright FVC. Sniff nasal inspiratory pressure (SNIP) is a rapid, convenient test of diaphragm strength that is not affected by bulbar muscle weakness. If someone with ALS has signs and symptoms of respiratory failure, they should undergo daytime blood gas analysis to look for hypoxemia (low oxygen in the blood) and hypercapnia (too much carbon dioxide in the blood). If their daytime blood gas analysis is normal, they should then have nocturnal pulse oximetry to look for hypoxemia during sleep.

Non-invasive ventilation prolongs survival longer than riluzole. A 2006 randomized controlled trial found that NIV prolongs survival by about 48 days and improves the quality of life; however, it also found that some people with ALS benefit more from this intervention than others. For those with normal or only moderately impaired bulbar function, NIV prolongs survival by about seven months and significantly improves the quality of life. For those with poor bulbar function, NIV neither prolongs survival nor improves the quality of life, though it does improve some sleep-related symptoms. Despite the clear benefits of NIV, about 25–30% of all people with ALS are unable to tolerate it, especially those with cognitive impairment or bulbar dysfunction. Results from a large 2015 cohort study suggest that NIV may prolong survival in those with bulbar weakness, so NIV should be offered to all people with ALS, even if it is likely that they will have difficulty tolerating it.

Invasive ventilation

Invasive ventilation bypasses the nose and mouth (the upper airways) by making a cut in the trachea (tracheostomy) and inserting a tube connected to a ventilator. It is an option for people with advanced ALS whose respiratory symptoms are poorly managed despite continuous NIV use. While invasive ventilation prolongs survival, especially for those younger than 60, it does not treat the underlying neurodegenerative process. The person with ALS will continue to lose motor function, making communication increasingly difficult and sometimes leading to locked-in syndrome, in which they are completely paralyzed except for their eye muscles. About half of the people with ALS who choose to undergo invasive ventilation report a decrease in their quality of life but most still consider it to be satisfactory. However, invasive ventilation imposes a heavy burden on caregivers and may decrease their quality of life. Attitudes toward invasive ventilation vary from country to country; about 30% of people with ALS in Japan choose invasive ventilation, versus less than 5% in North America and Europe.

Therapy

Physical therapy plays a large role in rehabilitation for individuals with ALS. Specifically, physical, occupational, and speech therapists can set goals and promote benefits for individuals with ALS by delaying loss of strength, maintaining endurance, limiting pain, improving speech and swallowing, preventing complications, and promoting functional independence.

Occupational therapy and special equipment such as assistive technology can also enhance people's independence and safety throughout the course of ALS. Gentle, low-impact aerobic exercise such as performing activities of daily living, walking, swimming, and stationary bicycling can strengthen unaffected muscles, improve cardiovascular health, and help people fight fatigue and depression. Range of motion and stretching exercises can help prevent painful spasticity and shortening (contracture) of muscles. Physical and occupational therapists can recommend exercises that provide these benefits without overworking muscles because muscle exhaustion can lead to a worsening of symptoms associated with ALS, rather than providing help to people with ALS. They can suggest devices such as ramps, braces, walkers, bathroom equipment (shower chairs, toilet risers, etc.), and wheelchairs that help people remain mobile. Occupational therapists can provide or recommend equipment and adaptations to enable ALS people to retain as much safety and independence in activities of daily living as possible. Since respiratory insufficiency is the primary cause of mortality, physical therapists can help improve respiratory outcomes in people with ALS by implementing pulmonary physical therapy. This includes inspiratory muscle training, lung volume recruitment training, and manual assisted cough therapy aimed at increasing respiratory muscle strength as well as increasing survival rates.

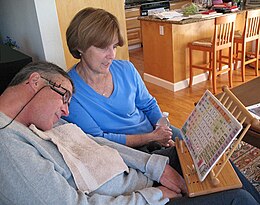

People with ALS who have difficulty speaking or swallowing may benefit from working with a speech-language pathologist. These health professionals can teach people adaptive strategies such as techniques to help them speak louder and more clearly. As ALS progresses, speech-language pathologists can recommend the use of augmentative and alternative communication such as voice amplifiers, speech-generating devices (or voice output communication devices), or low-tech communication techniques such as head-mounted laser pointers, alphabet boards or yes/no signals.

Nutrition

Preventing weight loss and malnutrition in people with ALS improves both survival and quality of life. Weight loss in ALS is often caused by muscle wasting and increased resting energy expenditure. Weight loss may also be secondary to reduced food intake since dysphagia develops in about 85% of people with ALS at some point throughout their disease course. Therefore, regular periodic assessment of the weight and swallowing ability in people with ALS is very important. Dysphagia is often initially managed via dietary changes and modified swallowing techniques. People with ALS are often instructed to avoid dry or chewy foods in their diet and instead have meals that are soft, moist, and easy to swallow. Switching to thick liquids (like fruit nectar or smoothies) or adding thickeners (to thin fluids like water and coffee) may also help people facing difficulty swallowing liquids. There is tentative evidence that high-calorie diets may prevent further weight loss and improve survival, but more research is still needed.

A feeding tube should be considered if someone with ALS loses 5% or more of their body weight or if they cannot safely swallow food and water. This can take the form of a gastrostomy tube, in which a tube is placed through the wall of the abdomen into the stomach, or (less commonly) a nasogastric tube, in which a tube is placed through the nose and down the esophagus into the stomach. A gastrostomy tube is more appropriate for long-term use than a nasogastric tube, which is uncomfortable and can cause esophageal ulcers. The feeding tube is usually inserted by a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy procedure (PEG). While there is weak evidence that PEG tubes improve survival in people with ALS, no randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have yet been conducted to indicate whether enteral tube feeding has benefits compared to continuation of feeding by mouth. Nevertheless, PEG tubes are still offered with the intent of improving the person's quality of life by sustaining nutrition, hydration status, and medication intake.

End-of-life care

Palliative care, which relieves symptoms and improves the quality of life without treating the underlying disease, should begin shortly after someone is diagnosed with ALS. Early discussion of end-of-life issues gives people with ALS time to reflect on their preferences for end-of-life care and can help avoid unwanted interventions or procedures. Once they have been fully informed about all aspects of various life-prolonging measures, they can fill out advance directives indicating their attitude toward noninvasive ventilation, invasive ventilation, and feeding tubes. Late in the disease course, difficulty speaking due to muscle weakness (dysarthria) and cognitive dysfunction may impair their ability to communicate their wishes regarding care. Continued failure to solicit the preferences of the person with ALS may lead to unplanned and potentially unwanted emergency interventions, such as invasive ventilation. If people with ALS or their family members are reluctant to discuss end-of-life issues, it may be useful to use the introduction of gastrostomy or noninvasive ventilation as an opportunity to bring up the subject.

Hospice care, or palliative care at the end of life, is especially important in ALS because it helps to optimize the management of symptoms and increases the likelihood of a peaceful death. It is unclear exactly when the end-of-life phase begins in ALS, but it is associated with significant difficulty moving, communicating, and, in some cases, thinking. Although many people with ALS fear choking to death (suffocating), they can be reassured that this occurs rarely, less than 1% of the time. Most patients die at home, and in the final days of life, opioids can be used to treat pain and dyspnea, while benzodiazepines can be used to treat anxiety.

Epidemiology

ALS is the most common motor neuron disease in adults and the third most common neurodegenerative disease after Alzheimer's disease and Parkinson's disease. Worldwide the number of people who develop ALS yearly is estimated to be 1.9 people per 100,000 per year, while the number of people who have ALS at any given time is estimated to be about 4.5 people per 100,000. In Europe, the number of new cases a year is about 2.6 people per 100,000, while the number affected is 7–9 people per 100,000. The lifetime risk of developing ALS is 1:350 for European men and 1:400 for European women. Men have a higher risk mainly because spinal-onset ALS is more common in men than women. The number of those with ALS in the United States in 2015 was 5.2 people per 100,000, and was higher in whites, males, and people over 60 years old. The number of new cases is about 0.8 people per 100,000 per year in East Asia and about 0.7 people per 100,000 per year in South Asia. About 80% of ALS epidemiology studies have been conducted in Europe and the United States, mostly in people of northern European descent. There is not enough information to determine the rates of ALS in much of the world, including Africa, parts of Asia, India, Russia, and South America. There are several geographic clusters in the Western Pacific where the prevalence of ALS was reported to be 50–100 times higher than in the rest of the world, including Guam, the Kii Peninsula of Japan, and Western New Guinea. The incidence in these areas has decreased since the 1960s; the cause remains unknown.

People of all races and ethnic backgrounds may be affected by ALS, but it is more common in whites than in Africans, Asians, or Hispanics. In the United States in 2015, the prevalence of ALS in whites was 5.4 people per 100,000, while the prevalence in blacks was 2.3 people per 100,000. The Midwest had the highest prevalence of the four US Census regions with 5.5 people per 100,000, followed by the Northeast (5.1), the South (4.7), and the West (4.4). The Midwest and Northeast likely had a higher prevalence of ALS because they have a higher proportion of whites than the South and West. Ethnically mixed populations may be at a lower risk of developing ALS; a study in Cuba found that people of mixed ancestry were less likely to die from ALS than whites or blacks. There are also differences in the genetics of ALS between different ethnic groups; the most common ALS gene in Europe is C9orf72, followed by SOD1, TARDBP, and FUS, while the most common ALS gene in Asia is SOD1, followed by FUS, C9orf72, and TARDBP.

ALS can affect people at any age, but the peak incidence is between 50 and 75 years and decreases dramatically after 80 years. The reason for the decreased incidence in the elderly is unclear. One thought is that people who survive into their 80s may not be genetically susceptible to developing ALS; alternatively, ALS in the elderly might go undiagnosed because of comorbidities (other diseases they have), difficulty seeing a neurologist, or dying quickly from an aggressive form of ALS. In the United States in 2015, the lowest prevalence was in the 18–39 age group, while the highest prevalence was in the 70–79 age group. Sporadic ALS usually starts around the ages of 58 to 63 years, while genetic ALS starts earlier, usually around 47 to 52 years. The number of ALS cases worldwide is projected to increase from 222,801 in 2015 to 376,674 in 2040, an increase of 69%. This will largely be due to the aging of the world's population, especially in developing countries.

History

Descriptions of the disease date back to at least 1824 by Charles Bell. In 1850, François-Amilcar Aran was the first to describe a disorder he named "progressive muscular atrophy", a form of ALS in which only the lower motor neurons are affected. In 1869, the connection between the symptoms and the underlying neurological problems was first described by Jean-Martin Charcot, who initially introduced the term amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in his 1874 paper. Flail arm syndrome, a regional variant of ALS, was first described by Alfred Vulpian in 1886. Flail leg syndrome, another regional variant of ALS, was first described by Pierre Marie and his student Patrikios in 1918.

Diagnostic criteria

In the 1950s, electrodiagnostic testing (EMG) and nerve conduction velocity (NCV) testing began to be used to evaluate clinically suspected ALS. In 1969 Edward H. Lambert published the first EMG/NCS diagnostic criteria for ALS, consisting of four findings he considered to strongly support the diagnosis. Since then several diagnostic criteria have been developed, which are mostly in use for research purposes for inclusion/exclusion criteria, and to stratify patients for analysis in trials. Research diagnostic criteria for ALS include the "El Escorial" in 1994, revised in 1998. In 2006, the "Awaji" criteria proposed using EMG and NCV tests to help diagnose ALS earlier, and most recently the "Gold Coast" criteria in 2019.

Name

See also: Motor neuron diseasesAmyotrophic comes from Greek: a- means "no", myo- (from mûs) refers to "muscle", and trophḗ means "nourishment". Therefore, amyotrophy means "muscle malnourishment" or the wasting of muscle tissue. Lateral identifies the locations in the spinal cord of the affected motor neurons. Sclerosis means "scarring" or "hardening" and refers to the death of the motor neurons in the spinal cord.

ALS is sometimes referred to as Charcot's disease (not to be confused with Charcot–Marie–Tooth disease or Charcot joint disease), because Jean-Martin Charcot was the first to connect the clinical symptoms with the pathology seen at autopsy. The British neurologist Russell Brain coined the term motor neurone disease in 1933 to reflect his belief that ALS, progressive bulbar palsy, and progressive muscular atrophy were all different forms of the same disease. In some countries, especially the United States, ALS is called Lou Gehrig's disease after the American baseball player Lou Gehrig, who was diagnosed with ALS in 1939.

In the United States and continental Europe, the term ALS (as well as Lou Gehrig's disease in the US) refers to all forms of the disease, including "classical" ALS, progressive bulbar palsy, progressive muscular atrophy, and primary lateral sclerosis. In the United Kingdom and Australia, the term motor neurone disease refers to all forms of the disease while ALS only refers to "classical" ALS, meaning the form with both upper and lower motor neuron involvement.

Society and culture

In addition to the baseball player Lou Gehrig and the theoretical physicist Stephen Hawking (who notably lived longer than any other known person with the condition), several other notable individuals have or have had ALS. Several books have been written and films have been made about patients of the disease as well. American sociology professor and ALS patient Morrie Schwartz was the subject of the memoir Tuesdays with Morrie and the film of the same name, and Stephen Hawking was the subject of the critically acclaimed biopic The Theory of Everything.

In August 2014, the "Ice Bucket Challenge" to raise money for ALS research went viral online. Participants filmed themselves filling a bucket full of ice water and pouring it onto themselves; they then nominated other individuals to do the same. Many participants donated to ALS research at the ALS Association, the ALS Therapy Development Institute, ALS Society of Canada, or Motor Neurone Disease Association in the UK.

References

- ^ Wijesekera LC, Leigh PN (February 2009). "Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis". Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases. 4 (4): 3. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-4-3. PMC 2656493. PMID 19192301.

- ^ Masrori P, Van Damme P (October 2020). "Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a clinical review". European Journal of Neurology. 27 (10): 1918–1929. doi:10.1111/ene.14393. PMC 7540334. PMID 32526057.

- ^ "Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) Fact Sheet". National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Archived from the original on 5 January 2017. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- Kwan J, Vullaganti M (September 2022). "Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis mimics". Muscle & Nerve. 66 (3): 240–252. doi:10.1002/mus.27567. PMID 35607838. S2CID 249014375.

- ^ Hobson EV, McDermott CJ (September 2016). "Supportive and symptomatic management of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis" (PDF). Nature Reviews. Neurology. 12 (9): 526–538. doi:10.1038/nrneurol.2016.111. PMID 27514291. S2CID 8547381. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 December 2020. Retrieved 20 December 2019.

- ^ Goutman SA, Hardiman O, Al-Chalabi A, Chió A, Savelieff MG, Kiernan MC, et al. (May 2022). "Recent advances in the diagnosis and prognosis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis". The Lancet. Neurology. 21 (5): 480–493. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(21)00465-8. PMC 9513753. PMID 35334233.

- Ryan M, Heverin M, McLaughlin RL, Hardiman O (November 2019). "Lifetime Risk and Heritability of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis". JAMA Neurology. 76 (11): 1367–1374. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.2044. PMC 6646974. PMID 31329211.

- "Motor Neuron Diseases Fact Sheet". www.ninds.nih.gov. National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Archived from the original on 10 October 2020. Retrieved 27 October 2020.

- ^ van Es MA, Hardiman O, Chio A, Al-Chalabi A, Pasterkamp RJ, Veldink JH, et al. (November 2017). "Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis". Lancet. 390 (10107): 2084–2098. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31287-4. PMID 28552366. S2CID 24483077.

- ^ Hardiman O, Al-Chalabi A, Chio A, Corr EM, Logroscino G, Robberecht W, et al. (October 2017). "Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis" (PDF). Nature Reviews. Disease Primers. 3 (17071): 17071. doi:10.1038/nrdp.2017.71. PMID 28980624. S2CID 1002680. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 December 2020. Retrieved 20 December 2019.

- "Understanding ALS". The ALS Association. Archived from the original on 26 October 2020. Retrieved 28 October 2020.

- ^ Wingo TS, Cutler DJ, Yarab N, Kelly CM, Glass JD (2011). "The heritability of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in a clinically ascertained United States research registry". PLOS ONE. 6 (11): e27985. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...627985W. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0027985. PMC 3222666. PMID 22132186.

- "Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis". MedlinePlus Genetics. Retrieved 7 August 2023.

- ^ Goutman SA, Hardiman O, Al-Chalabi A, Chió A, Savelieff MG, Kiernan MC, et al. (May 2022). "Emerging insights into the complex genetics and pathophysiology of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis". The Lancet. Neurology. 21 (5): 465–479. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(21)00414-2. PMC 9513754. PMID 35334234.

- ^ "FDA-Approved Drugs for Treating ALS". The ALS Association. Archived from the original on 25 April 2023. Retrieved 25 April 2023.

- ^ Soriani MH, Desnuelle C (May 2017). "Care management in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis". Revue Neurologique. 173 (5): 288–299. doi:10.1016/j.neurol.2017.03.031. PMID 28461024.

- ^ Connolly S, Galvin M, Hardiman O (April 2015). "End-of-life management in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis". The Lancet. Neurology. 14 (4): 435–442. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70221-2. PMID 25728958. S2CID 34109901.

- ^ Kiernan MC, Vucic S, Cheah BC, Turner MR, Eisen A, Hardiman O, et al. (March 2011). "Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis". Lancet. 377 (9769): 942–955. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(10)61156-7. PMID 21296405.

- ^ Pupillo E, Messina P, Logroscino G, Beghi E (February 2014). "Long-term survival in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a population-based study". Annals of Neurology. 75 (2): 287–297. doi:10.1002/ana.24096. PMID 24382602. S2CID 205345019.

- ^ Rowland LP (March 2001). "How amyotrophic lateral sclerosis got its name: the clinical-pathologic genius of Jean-Martin Charcot". Archives of Neurology. 58 (3): 512–515. doi:10.1001/archneur.58.3.512. PMID 11255459.

- "8B60 Motor neuron disease". ICD-11 for Mortality and Morbidity Statistics. World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 1 August 2018. Retrieved 24 January 2019.

- van Eenennaam RM, Koppenol LS, Kruithof WJ, Kruitwagen-van Reenen ET, Pieters S, van Es MA, et al. (November 2021). "Discussing Personalized Prognosis Empowers Patients with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis to Regain Control over Their Future: A Qualitative Study". Brain Sciences. 11 (12): 1597. doi:10.3390/brainsci11121597. PMC 8699408. PMID 34942899.

- ^ Grad LI, Rouleau GA, Ravits J, Cashman NR (August 2017). "Clinical Spectrum of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS)". Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine. 7 (8): a024117. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a024117. PMC 5538408. PMID 28003278.

- ^ Arora RD, Khan YS (2023). "Motor Neuron Disease". StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. PMID 32809609. Retrieved 27 August 2023.

- Gautier G, Verschueren A, Monnier A, Attarian S, Salort-Campana E, Pouget J (August 2010). "ALS with respiratory onset: clinical features and effects of non-invasive ventilation on the prognosis". Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. 11 (4): 379–382. doi:10.3109/17482960903426543. PMID 20001486. S2CID 27672209.

- ^ Swinnen B, Robberecht W (November 2014). "The phenotypic variability of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis". Nature Reviews. Neurology. 10 (11): 661–670. doi:10.1038/nrneurol.2014.184. PMID 25311585. S2CID 205516010. Archived from the original on 31 December 2018. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- ^ Al-Chalabi A, Hardiman O, Kiernan MC, Chiò A, Rix-Brooks B, van den Berg LH (October 2016). "Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: moving towards a new classification system". The Lancet. Neurology. 15 (11): 1182–1194. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(16)30199-5. hdl:2318/1636249. PMID 27647646. S2CID 45285510.

- Jawdat O, Statland JM, Barohn RJ, Katz JS, Dimachkie MM (November 2015). "Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Regional Variants (Brachial Amyotrophic Diplegia, Leg Amyotrophic Diplegia, and Isolated Bulbar Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis)". Neurological Clinics. 33 (4): 775–785. doi:10.1016/j.ncl.2015.07.003. PMC 4629514. PMID 26515621.

- Zhang H, Chen L, Tian J, Fan D (October 2021). "Disease duration of progression is helpful in identifying isolated bulbar palsy of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis". BMC Neurology. 21 (1): 405. doi:10.1186/s12883-021-02438-8. PMC 8532334. PMID 34686150.

- Lehky T, Grunseich C (November 2021). "Juvenile Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: A Review". Genes. 12 (12): 1935. doi:10.3390/genes12121935. PMC 8701111. PMID 34946884.

- Teoh HL, Carey K, Sampaio H, Mowat D, Roscioli T, Farrar M (2017). "Inherited Paediatric Motor Neuron Disorders: Beyond Spinal Muscular Atrophy". Neural Plasticity. 2017: 6509493. doi:10.1155/2017/6509493. PMC 5467325. PMID 28634552.

- ^ Tard C, Defebvre L, Moreau C, Devos D, Danel-Brunaud V (May 2017). "Clinical features of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and their prognostic value". Revue Neurologique. 173 (5): 263–272. doi:10.1016/j.neurol.2017.03.029. PMID 28477850.

- Ravits J, Appel S, Baloh RH, Barohn R, Brooks BR, Elman L, et al. (May 2013). "Deciphering amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: what phenotype, neuropathology and genetics are telling us about pathogenesis". Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis & Frontotemporal Degeneration. 14 (Suppl 1): 5–18. doi:10.3109/21678421.2013.778548. PMC 3779649. PMID 23678876.

- "Motor neurone disease". UK: National Health Service. 15 January 2018. Archived from the original on 29 December 2014. Retrieved 24 October 2020.

- ^ Chiò A, Mora G, Lauria G (February 2017). "Pain in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis". The Lancet. Neurology. 16 (2): 144–157. arXiv:1607.02870. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(16)30358-1. PMID 27964824. S2CID 38905437.

- Gromicho M, Figueiral M, Uysal H, Grosskreutz J, Kuzma-Kozakiewicz M, Pinto S, et al. (July 2020). "Spreading in ALS: The relative impact of upper and lower motor neuron involvement". Annals of Clinical and Translational Neurology. 7 (7): 1181–1192. doi:10.1002/acn3.51098. PMC 7359118. PMID 32558369.

- Cedarbaum JM, Stambler N, Malta E, Fuller C, Hilt D, Thurmond B, et al. (October 1999). "The ALSFRS-R: a revised ALS functional rating scale that incorporates assessments of respiratory function. BDNF ALS Study Group (Phase III)". Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 169 (1–2): 13–21. doi:10.1016/s0022-510x(99)00210-5. PMID 10540002. S2CID 7057926.

- Wong C, Stavrou M, Elliott E, Gregory JM, Leigh N, Pinto AA, et al. (2021). "Clinical trials in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a systematic review and perspective". Brain Communications. 3 (4): fcab242. doi:10.1093/braincomms/fcab242. PMC 8659356. PMID 34901853.

- Creemers H, Grupstra H, Nollet F, van den Berg LH, Beelen A (June 2015). "Prognostic factors for the course of functional status of patients with ALS: a systematic review". Journal of Neurology. 262 (6): 1407–1423. doi:10.1007/s00415-014-7564-8. PMID 25385051. S2CID 31734765.

- Atassi N, Berry J, Shui A, Zach N, Sherman A, Sinani E, et al. (November 2014). "The PRO-ACT database: design, initial analyses, and predictive features". Neurology. 83 (19): 1719–1725. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000000951. PMC 4239834. PMID 25298304.

- ^ Bedlack RS, Vaughan T, Wicks P, Heywood J, Sinani E, Selsov R, et al. (March 2016). "How common are ALS plateaus and reversals?". Neurology. 86 (9): 808–812. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000002251. PMC 4793781. PMID 26658909.

- Castrillo-Viguera C, Grasso DL, Simpson E, Shefner J, Cudkowicz ME (2010). "Clinical significance in the change of decline in ALSFRS-R". Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (Journal Article). 11 (1–2): 178–180. doi:10.3109/17482960903093710. PMID 19634063. S2CID 207619689.

- ^ Yunusova Y, Plowman EK, Green JR, Barnett C, Bede P (2019). "Clinical Measures of Bulbar Dysfunction in ALS". Frontiers in Neurology. 10: 106. doi:10.3389/fneur.2019.00106. PMC 6389633. PMID 30837936.

- Lui AJ, Byl NN (June 2009). "A systematic review of the effect of moderate intensity exercise on function and disease progression in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis". Journal of Neurologic Physical Therapy. 33 (2): 68–87. doi:10.1097/NPT.0b013e31819912d0. PMID 19556916. S2CID 7650356.

- Beukelman D, Fager S, Nordness A (2011). "Communication Support for People with ALS". Neurology Research International. 2011: 714693. doi:10.1155/2011/714693. PMC 3096454. PMID 21603029.

- Kuzma-Kozakiewicz M, Andersen PM, Ciecwierska K, Vázquez C, Helczyk O, Loose M, et al. (September 2019). "An observational study on quality of life and preferences to sustain life in locked-in state". Neurology. 93 (10): e938 – e945. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000008064. PMC 6745736. PMID 31391247.

- O'Brien D, Stavroulakis T, Baxter S, Norman P, Bianchi S, Elliott M, et al. (September 2019). "The optimisation of noninvasive ventilation in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a systematic review". The European Respiratory Journal. 54 (3): 1900261. doi:10.1183/13993003.00261-2019. PMID 31273038. S2CID 195805546.

- ^ Bede P, Oliver D, Stodart J, van den Berg L, Simmons Z, O Brannagáin D, et al. (April 2011). "Palliative care in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a review of current international guidelines and initiatives". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 82 (4): 413–418. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2010.232637. hdl:2262/59035. PMID 21297150. S2CID 7043837. Archived from the original on 28 May 2023. Retrieved 30 April 2023.

- Corcia P, Pradat PF, Salachas F, Bruneteau G, Forestier N, Seilhean D, et al. (1 January 2008). "Causes of death in a post-mortem series of ALS patients". Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. 9 (1): 59–62. doi:10.1080/17482960701656940. PMID 17924236. S2CID 40367873.

- Fang T, Al Khleifat A, Stahl DR, Lazo La Torre C, Murphy C, Young C, et al. (May 2017). "Comparison of the King's and MiToS staging systems for ALS". Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis & Frontotemporal Degeneration. 18 (3–4): 227–232. doi:10.1080/21678421.2016.1265565. PMC 5425622. PMID 28054828.

- ^ Chiò A, Calvo A, Moglia C, Mazzini L, Mora G (July 2011). "Phenotypic heterogeneity of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a population based study" (PDF). Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 82 (7): 740–746. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2010.235952. PMID 21402743. S2CID 13416164. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 November 2022. Retrieved 4 August 2022.

- Landau E (20 September 2009). "Stephen Hawking serves as role model for ALS patients". CNN. Archived from the original on 15 August 2016.

- ^ Martin S, Al Khleifat A, Al-Chalabi A (2017). "What causes amyotrophic lateral sclerosis?". F1000Research. 6: 371. doi:10.12688/f1000research.10476.1. PMC 5373425. PMID 28408982.

- ^ Crockford C, Newton J, Lonergan K, Chiwera T, Booth T, Chandran S, et al. (October 2018). "ALS-specific cognitive and behavior changes associated with advancing disease stage in ALS". Neurology. 91 (15): e1370 – e1380. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000006317. PMC 6177274. PMID 30209236.

- Yang T, Hou Y, Li C, Cao B, Cheng Y, Wei Q, et al. (July 2021). "Risk factors for cognitive impairment in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 92 (7): 688–693. doi:10.1136/jnnp-2020-325701. PMID 33563800. S2CID 231858696.

- Wicks P (July 2007). "Excessive yawning is common in the bulbar-onset form of ALS". Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 116 (1): 76, author reply 76–76, author reply 77. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2007.01025.x. PMID 17559605. S2CID 12807996.

- Sauvé WM (December 2016). "Recognizing and treating pseudobulbar affect". CNS Spectrums. 21 (S1): 34–44. doi:10.1017/S1092852916000791. PMID 28044945. S2CID 21066800.

- Raaphorst J, Beeldman E, De Visser M, De Haan RJ, Schmand B (October 2012). "A systematic review of behavioural changes in motor neuron disease". Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. 13 (6): 493–501. doi:10.3109/17482968.2012.656652. PMID 22424127. S2CID 22224140.

- Couratier P, Corcia P, Lautrette G, Nicol M, Marin B (May 2017). "ALS and frontotemporal dementia belong to a common disease spectrum". Revue Neurologique. 173 (5): 273–279. doi:10.1016/j.neurol.2017.04.001. PMID 28449882.

- ^ Renton AE, Chiò A, Traynor BJ (January 2014). "State of play in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis genetics". Nature Neuroscience. 17 (1): 17–23. doi:10.1038/nn.3584. hdl:2318/156177. PMC 4544832. PMID 24369373.

- Beeldman E, Raaphorst J, Klein Twennaar M, de Visser M, Schmand BA, de Haan RJ (June 2016). "The cognitive profile of ALS: a systematic review and meta-analysis update". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 87 (6): 611–619. doi:10.1136/jnnp-2015-310734. PMID 26283685. S2CID 22082109.

- ^ Al-Chalabi A, Hardiman O (November 2013). "The epidemiology of ALS: a conspiracy of genes, environment and time". Nature Reviews. Neurology. 9 (11): 617–628. doi:10.1038/nrneurol.2013.203. PMID 24126629. S2CID 25040863.

- ^ "Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) - Symptoms and causes". Mayo Clinic. Archived from the original on 6 April 2022. Retrieved 6 April 2022.

- ^ "Who Gets ALS?". The ALS Association. Archived from the original on 6 April 2022. Retrieved 6 April 2022.

- He J, Mangelsdorf M, Fan D, Bartlett P, Brown MA (December 2015). "Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Genetic Studies: From Genome-wide Association Mapping to Genome Sequencing" (PDF). The Neuroscientist. 21 (6): 599–615. doi:10.1177/1073858414555404. PMID 25378359. S2CID 3437565. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 May 2020. Retrieved 20 December 2019.

- McNeill A, Amador MD, Bekker H, Clarke A, Crook A, Cummings C, et al. (June 2022). "Predictive genetic testing for Motor neuron disease: time for a guideline?". European Journal of Human Genetics. 30 (6): 635–636. doi:10.1038/s41431-022-01093-y. PMC 9177585. PMID 35379930.

- De Oliveira HM, Soma A, Baker MR, Turner MR, Talbot K, Williams TL (August 2023). "A survey of current practice in genetic testing in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in the UK and Republic of Ireland: implications for future planning". Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis & Frontotemporal Degeneration. 24 (5–6): 405–413. doi:10.1080/21678421.2022.2150556. PMID 36458618. S2CID 254150195.

- Müller K, Oh KW, Nordin A, Panthi S, Kim SH, Nordin F, et al. (February 2022). "De novo mutations in SOD1 are a cause of ALS". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 93 (2): 201–206. doi:10.1136/jnnp-2021-327520. PMC 8784989. PMID 34518333.

- McNeill A, Amador MD, Bekker H, Clarke A, Crook A, Cummings C, et al. (International Alliance of ALS/MND Associations) (June 2022). "Predictive genetic testing for Motor neuron disease: time for a guideline?". European Journal of Human Genetics. 30 (6): 635–636. doi:10.1038/s41431-022-01093-y. PMC 9177585. PMID 35379930.

- Salmon K, Kiernan MC, Kim SH, Andersen PM, Chio A, van den Berg LH, et al. (May 2022). "The importance of offering early genetic testing in everyone with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis". Brain. 145 (4): 1207–1210. doi:10.1093/brain/awab472. PMC 9129091. PMID 35020823. Archived from the original on 27 May 2023. Retrieved 27 May 2023.

- ^ Wang MD, Little J, Gomes J, Cashman NR, Krewski D (July 2017). "Identification of risk factors associated with onset and progression of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis using systematic review and meta-analysis". Neurotoxicology. 61: 101–130. Bibcode:2017NeuTx..61..101W. doi:10.1016/j.neuro.2016.06.015. PMID 27377857. S2CID 33604904. Archived from the original on 17 November 2022. Retrieved 27 May 2023.

- Vitturi BK, Montecucco A, Rahmani A, Dini G, Durando P (15 November 2023). "Occupational risk factors for multiple sclerosis: a systematic review with meta-analysis". Frontiers in Public Health. 11 (2023). doi:10.3389/fpubh.2023.1285103. PMC 10694508. Retrieved 3 January 2025.

- ^ Grossman AB, Levin BE, Bradley WG (March 2006). "Premorbid personality characteristics of patients with ALS". Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. 7 (1): 27–31. doi:10.1080/14660820510012004. PMID 16546756. S2CID 20998807.

- ^ Parkin Kullmann JA, Hayes S, Pamphlett R (October 2018). "Are people with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) particularly nice? An international online case-control study of the Big Five personality factors". Brain and Behavior. 8 (10): e01119. doi:10.1002/brb3.1119. PMC 6192405. PMID 30239176.

- Mehl T, Jordan B, Zierz S (January 2017). ""Patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) are usually nice persons"-How physicians experienced in ALS see the personality characteristics of their patients". Brain and Behavior. 7 (1): e00599. doi:10.1002/brb3.599. PMC 5256182. PMID 28127517.

- Robberecht W, Philips T (April 2013). "The changing scene of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis". Nature Reviews. Neuroscience. 14 (4): 248–264. doi:10.1038/nrn3430. PMID 23463272. S2CID 208941.

- ^ Brown RH, Al-Chalabi A (July 2017). "Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis". The New England Journal of Medicine. 377 (2): 162–172. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1603471. PMID 28700839. S2CID 205117619. Archived from the original on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 20 December 2019.

- Okamoto K, Mizuno Y, Fujita Y (April 2008). "Bunina bodies in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis". Neuropathology. 28 (2): 109–115. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1789.2007.00873.x. PMID 18069968. S2CID 34398467.

- White JA, Banerjee R, Gunawardena S (May 2016). "Axonal Transport and Neurodegeneration: How Marine Drugs Can Be Used for the Development of Therapeutics". Marine Drugs. 14 (5): 102. doi:10.3390/md14050102. PMC 4882576. PMID 27213408.

- Ng Kee Kwong KC, Mehta AR, Nedergaard M, Chandran S (August 2020). "Defining novel functions for cerebrospinal fluid in ALS pathophysiology". Acta Neuropathologica Communications. 8 (1): 140. doi:10.1186/s40478-020-01018-0. PMC 7439665. PMID 32819425.

- Van Damme P, Robberecht W, Van Den Bosch L (May 2017). "Modelling amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: progress and possibilities". Disease Models & Mechanisms. 10 (5): 537–549. doi:10.1242/dmm.029058. PMC 5451175. PMID 28468939.

- Alsultan AA, Waller R, Heath PR, Kirby J (2016). "The genetics of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: current insights". Degenerative Neurological and Neuromuscular Disease. 6: 49–64. doi:10.2147/DNND.S84956. PMC 6053097. PMID 30050368.

- Shang Y, Huang EJ (September 2016). "Mechanisms of FUS mutations in familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis". Brain Research. 1647: 65–78. doi:10.1016/j.brainres.2016.03.036. PMC 5003642. PMID 27033831.

- Nguyen HP, Van Broeckhoven C, van der Zee J (June 2018). "ALS Genes in the Genomic Era and their Implications for FTD". Trends in Genetics. 34 (6): 404–423. doi:10.1016/j.tig.2018.03.001. hdl:10067/1514730151162165141. PMID 29605155.

- Gitler AD, Tsuiji H (September 2016). "There has been an awakening: Emerging mechanisms of C9orf72 mutations in FTD/ALS". Brain Research. 1647: 19–29. doi:10.1016/j.brainres.2016.04.004. PMC 5003651. PMID 27059391.