In computer science, a mutator method is a method used to control changes to a variable. They are also widely known as setter methods. Often a setter is accompanied by a getter, which returns the value of the private member variable. They are also known collectively as accessors.

The mutator method is most often used in object-oriented programming, in keeping with the principle of encapsulation. According to this principle, member variables of a class are made private to hide and protect them from other code, and can only be modified by a public member function (the mutator method), which takes the desired new value as a parameter, optionally validates it, and modifies the private member variable. Mutator methods can be compared to assignment operator overloading but they typically appear at different levels of the object hierarchy.

Mutator methods may also be used in non-object-oriented environments. In this case, a reference to the variable to be modified is passed to the mutator, along with the new value. In this scenario, the compiler cannot restrict code from bypassing the mutator method and changing the variable directly. The responsibility falls to the developers to ensure the variable is only modified through the mutator method and not modified directly.

In programming languages that support them, properties offer a convenient alternative without giving up the utility of encapsulation.

In the examples below, a fully implemented mutator method can also validate the input data or take further action such as triggering an event.

Implications

The alternative to defining mutator and accessor methods, or property blocks, is to give the instance variable some visibility other than private and access it directly from outside the objects. Much finer control of access rights can be defined using mutators and accessors. For example, a parameter may be made read-only simply by defining an accessor but not a mutator. The visibility of the two methods may be different; it is often useful for the accessor to be public while the mutator remains protected, package-private or internal.

The block where the mutator is defined provides an opportunity for validation or preprocessing of incoming data. If all external access is guaranteed to come through the mutator, then these steps cannot be bypassed. For example, if a date is represented by separate private year, month and day variables, then incoming dates can be split by the setDate mutator while for consistency the same private instance variables are accessed by setYear and setMonth. In all cases month values outside of 1 - 12 can be rejected by the same code.

Accessors conversely allow for synthesis of useful data representations from internal variables while keeping their structure encapsulated and hidden from outside modules. A monetary getAmount accessor may build a string from a numeric variable with the number of decimal places defined by a hidden currency parameter.

Modern programming languages often offer the ability to generate the boilerplate for mutators and accessors in a single line—as for example C#'s public string Name { get; set; } and Ruby's attr_accessor :name. In these cases, no code blocks are created for validation, preprocessing or synthesis. These simplified accessors still retain the advantage of encapsulation over simple public instance variables, but it is common that, as system designs progress, the software is maintained and requirements change, the demands on the data become more sophisticated. Many automatic mutators and accessors eventually get replaced by separate blocks of code. The benefit of automatically creating them in the early days of the implementation is that the public interface of the class remains identical whether or not greater sophistication is added, requiring no extensive refactoring if it is.

Manipulation of parameters that have mutators and accessors from inside the class where they are defined often requires some additional thought. In the early days of an implementation, when there is little or no additional code in these blocks, it makes no difference if the private instance variable is accessed directly or not. As validation, cross-validation, data integrity checks, preprocessing or other sophistication is added, subtle bugs may appear where some internal access makes use of the newer code while in other places it is bypassed.

Accessor functions can be less efficient than directly fetching or storing data fields due to the extra steps involved, however such functions are often inlined which eliminates the overhead of a function call.

Examples

Assembly

student struct

age dd ?

student ends

.code

student_get_age proc object:DWORD

mov ebx, object

mov eax, student.age

ret

student_get_age endp

student_set_age proc object:DWORD, age:DWORD

mov ebx, object

mov eax, age

mov student.age, eax

ret

student_set_age endp

C

In file student.h:

#ifndef _STUDENT_H #define _STUDENT_H struct student; /* opaque structure */ typedef struct student student; student *student_new(int age, char *name); void student_delete(student *s); void student_set_age(student *s, int age); int student_get_age(student *s); char *student_get_name(student *s); #endif

In file student.c:

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

#include "student.h"

struct student {

int age;

char *name;

};

student *student_new(int age, char *name) {

student *s = malloc(sizeof(student));

s->name = strdup(name);

s->age = age;

return s;

}

void student_delete(student *s) {

free(s->name);

free(s);

}

void student_set_age(student *s, int age) {

s->age = age;

}

int student_get_age(student *s) {

return s->age;

}

char *student_get_name(student *s) {

return s->name;

}

In file main.c:

#include <stdio.h>

#include "student.h"

int main(void) {

student *s = student_new(19, "Maurice");

char *name = student_get_name(s);

int old_age = student_get_age(s);

printf("%s's old age = %i\n", name, old_age);

student_set_age(s, 21);

int new_age = student_get_age(s);

printf("%s's new age = %i\n", name, new_age);

student_delete(s);

return 0;

}

In file Makefile:

all: out.txt; cat $< out.txt: main; ./$< > $@ main: main.o student.o main.o student.o: student.h clean: ;$(RM) *.o out.txt main

C++

In file Student.h:

#ifndef STUDENT_H

#define STUDENT_H

#include <string>

class Student {

public:

Student(const std::string& name);

const std::string& name() const;

void name(const std::string& name);

private:

std::string name_;

};

#endif

In file Student.cpp:

#include "Student.h"

Student::Student(const std::string& name) : name_(name) {

}

const std::string& Student::name() const {

return name_;

}

void Student::name(const std::string& name) {

name_ = name;

}

C#

This example illustrates the C# idea of properties, which are a special type of class member. Unlike Java, no explicit methods are defined; a public 'property' contains the logic to handle the actions. Note use of the built-in (undeclared) variable value.

public class Student

{

private string name;

/// <summary>

/// Gets or sets student's name

/// </summary>

public string Name

{

get { return name; }

set { name = value; }

}

}

In later C# versions (.NET Framework 3.5 and above), this example may be abbreviated as follows, without declaring the private variable name.

public class Student

{

public string Name { get; set; }

}

Using the abbreviated syntax means that the underlying variable is no longer available from inside the class. As a result, the set portion of the property must be present for assignment. Access can be restricted with a set-specific access modifier.

public class Student

{

public string Name { get; private set; }

}

Common Lisp

In Common Lisp Object System, slot specifications within class definitions may specify any of the :reader, :writer and :accessor options (even multiple times) to define reader methods, setter methods and accessor methods (a reader method and the respective setf method). Slots are always directly accessible through their names with the use of with-slots and slot-value, and the slot accessor options define specialized methods that use slot-value.

CLOS itself has no notion of properties, although the MetaObject Protocol extension specifies means to access a slot's reader and writer function names, including the ones generated with the :accessor option.

The following example shows a definition of a student class using these slot options and direct slot access:

(defclass student ()

((name :initarg :name :initform "" :accessor student-name) ; student-name is setf'able

(birthdate :initarg :birthdate :initform 0 :reader student-birthdate)

(number :initarg :number :initform 0 :reader student-number :writer set-student-number)))

;; Example of a calculated property getter (this is simply a method)

(defmethod student-age ((self student))

(- (get-universal-time) (student-birthdate self)))

;; Example of direct slot access within a calculated property setter

(defmethod (setf student-age) (new-age (self student))

(with-slots (birthdate) self

(setf birthdate (- (get-universal-time) new-age))

new-age))

;; The slot accessing options generate methods, thus allowing further method definitions

(defmethod set-student-number :before (new-number (self student))

;; You could also check if a student with the new-number already exists.

(check-type new-number (integer 1 *)))

D

D supports a getter and setter function syntax. In version 2 of the language getter and setter class/struct methods should have the @property attribute.

class Student {

private char name_;

// Getter

@property char name() {

return this.name_;

}

// Setter

@property char name(char name_in) {

return this.name_ = name_in;

}

}

A Student instance can be used like this:

auto student = new Student;

student.name = "David"; // same effect as student.name("David")

auto student_name = student.name; // same effect as student.name()

Delphi

This is a simple class in Delphi language which illustrates the concept of public property for accessing a private field.

interface

type

TStudent = class

strict private

FName: string;

procedure SetName(const Value: string);

public

/// <summary>

/// Get or set the name of the student.

/// </summary>

property Name: string read FName write SetName;

end;

// ...

implementation

procedure TStudent.SetName(const Value: string);

begin

FName := Value;

end;

end.

Java

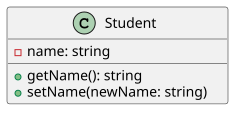

In this example of a simple class representing a student with only the name stored, one can see the variable name is private, i.e. only visible from the Student class, and the "setter" and "getter" are public, namely the "getName()" and "setName(name)" methods.

public class Student {

private String name;

public String getName() {

return name;

}

public void setName(String newName) {

name = newName;

}

}

JavaScript

In this example constructor-function Student is used to create objects representing a student with only the name stored.

function Student(name) {

var _name = name;

this.getName = function() {

return _name;

};

this.setName = function(value) {

_name = value;

};

}

Or (using a deprecated way to define accessors in Web browsers):

function Student(name){

var _name = name;

this.__defineGetter__('name', function() {

return _name;

});

this.__defineSetter__('name', function(value) {

_name = value;

});

}

Or (using prototypes for inheritance and ES6 accessor syntax):

function Student(name){

this._name = name;

}

Student.prototype = {

get name() {

return this._name;

},

set name(value) {

this._name = value;

}

};

Or (without using prototypes):

var Student = {

get name() {

return this._name;

},

set name(value) {

this._name = value;

}

};

Or (using defineProperty):

function Student(name){

this._name = name;

}

Object.defineProperty(Student.prototype, 'name', {

get: function() {

return this._name;

},

set: function(value) {

this._name = value;

}

});

ActionScript 3.0

package

{

public class Student

{

private var _name : String;

public function get name() : String

{

return _name;

}

public function set name(value : String) : void

{

_name = value;

}

}

}

Objective-C

Using traditional Objective-C 1.0 syntax, with manual reference counting as the one working on GNUstep on Ubuntu 12.04:

@interface Student : NSObject

{

NSString *_name;

}

- (NSString *)name;

- (void)setName:(NSString *)name;

@end

@implementation Student

- (NSString *)name

{

return _name;

}

- (void)setName:(NSString *)name

{

;

_name = ;

}

@end

Using newer Objective-C 2.0 syntax as used in Mac OS X 10.6, iOS 4 and Xcode 3.2, generating the same code as described above:

@interface Student : NSObject @property (nonatomic, retain) NSString *name; @end @implementation Student @synthesize name = _name; @end

And starting with OS X 10.8 and iOS 6, while using Xcode 4.4 and up, syntax can be even simplified:

@interface Student : NSObject @property (nonatomic, strong) NSString *name; @end @implementation Student //Nothing goes here and it's OK. @end

Perl

package Student;

sub new {

bless {}, shift;

}

sub set_name {

my $self = shift;

$self->{name} = $_;

}

sub get_name {

my $self = shift;

return $self->{name};

}

1;

Or, using Class::Accessor

package Student; use base qw(Class::Accessor); __PACKAGE__->follow_best_practice; Student->mk_accessors(qw(name)); 1;

Or, using the Moose Object System:

package Student; use Moose; # Moose uses the attribute name as the setter and getter, the reader and writer properties # allow us to override that and provide our own names, in this case get_name and set_name has 'name' => (is => 'rw', isa => 'Str', reader => 'get_name', writer => 'set_name'); 1;

PHP

PHP defines the "magic methods" __getand__set for properties of objects.

In this example of a simple class representing a student with only the name stored, one can see the variable name is private, i.e. only visible from the Student class, and the "setter" and "getter" is public, namely the getName() and setName('name') methods.

class Student

{

private string $name;

/**

* @return string The name.

*/

public function getName(): string

{

return $this->name;

}

/**

* @param string $newName The name to set.

*/

public function setName(string $newName): void

{

$this->name = $newName;

}

}

Python

This example uses a Python class with one variable, a getter, and a setter.

class Student:

# Initializer

def __init__(self, name: str) -> None:

# An instance variable to hold the student's name

self._name = name

# Getter method

@property

def name(self):

return self._name

# Setter method

@name.setter

def name(self, new_name):

self._name = new_name

>>> bob = Student("Bob")

>>> bob.name

Bob

>>> bob.name = "Alice"

>>> bob.name

Alice

>>> bob._name = "Charlie" # bypass the setter

>>> bob._name # bypass the getter

Charlie

Racket

In Racket, the object system is a way to organize code that comes in addition to modules and units. As in the rest of the language, the object system has first-class values and lexical scope is used to control access to objects and methods.

#lang racket

(define student%

(class object%

(init-field name)

(define/public (get-name) name)

(define/public (set-name! new-name) (set! name new-name))

(super-new)))

(define s (new student% ))

(send s get-name) ; => "Alice"

(send s set-name! "Bob")

(send s get-name) ; => "Bob"

Struct definitions are an alternative way to define new types of values, with mutators being present when explicitly required:

#lang racket (struct student (name) #:mutable) (define s (student "Alice")) (set-student-name! s "Bob") (student-name s) ; => "Bob"

Ruby

In Ruby, individual accessor and mutator methods may be defined, or the metaprogramming constructs attr_reader or attr_accessor may be used both to declare a private variable in a class and to provide either read-only or read-write public access to it respectively.

Defining individual accessor and mutator methods creates space for pre-processing or validation of the data

class Student

def name

@name

end

def name=(value)

@name=value

end

end

Read-only simple public access to implied @name variable

class Student attr_reader :name end

Read-write simple public access to implied @name variable

class Student attr_accessor :name end

Rust

struct Student {

name: String,

}

impl Student {

fn name(&self) -> &String {

&self.name

}

fn name_mut(&mut self) -> &mut String {

&mut self.name

}

}

Smalltalk

age: aNumber

" Set the receiver age to be aNumber if is greater than 0 and less than 150 "

(aNumber between: 0 and: 150)

ifTrue:

Swift

class Student {

private var _name: String = ""

var name: String {

get {

return self._name

}

set {

self._name = newValue

}

}

}

Visual Basic .NET

This example illustrates the VB.NET idea of properties, which are used in classes. Similar to C#, there is an explicit use of the Get and Set methods.

Public Class Student

Private _name As String

Public Property Name()

Get

Return _name

End Get

Set(ByVal value)

_name = value

End Set

End Property

End Class

In VB.NET 2010, Auto Implemented properties can be utilized to create a property without having to use the Get and Set syntax. Note that a hidden variable is created by the compiler, called _name, to correspond with the Property name. Using another variable within the class named _name would result in an error. Privileged access to the underlying variable is available from within the class.

Public Class Student

Public Property name As String

End Class

See also

References

- Stephen Fuqua (2009). "Automatic Properties in C# 3.0". Archived from the original on 2011-05-13. Retrieved 2009-10-19.

- Tim Lee (1998-07-13). "Run Time Efficiency of Accessor Functions".

- "CLHS: Macro DEFCLASS". Retrieved 2011-03-29.

- "CLHS: 7.5.2 Accessing Slots". Retrieved 2011-03-29.

- "MOP: Slot Definitions". Retrieved 2011-03-29.

- "Functions - D Programming Language". Retrieved 2013-01-13.

- "The D Style". Retrieved 2013-02-01.

- "Object.prototype.__defineGetter__() - JavaScript | MDN". developer.mozilla.org. Retrieved 2021-07-06.

- "PHP: Overloading - Manual". www.php.net. Retrieved 2021-07-06.