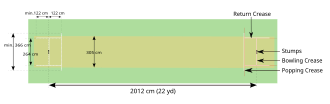

A cricket pitch consists of the central strip of a cricket field between the two wickets. It is 22 yd (20.12 m) long (1 chain) and 10 ft (3.05 m) wide. The surface is flat and is normally covered with extremely short grass, but can be completely dry or dusty soil with barely any grass or, in some circumstances (that are rarely seen in high level cricket), made from an artificial material. Over the course of a cricket match, the pitch is not repaired or altered other than in special circumstances - meaning that it will change condition. Any grass on the pitch in the game's first over, for example, may have disappeared by the twentieth over due to wear.

As almost all deliveries bowled will bounce off the pitch towards the batter, the state and type of a cricket pitch can significantly affect the outcome of a match. For example, a dusty, very dry, pitch will favour spin bowling because the ball will grip more on a dusty pitch - giving the team with the superior spin bowlers a significant advantage in the match. The state of the pitch is so important to the outcome of a cricket match that home teams can be fined or docked points if they produce a poor pitch that is deemed unfit for normal play, or seen to be a danger to batters by the ball behaving erratically when pitching on it. Players can face disciplinary action if they are seen to be deliberately damaging or altering the pitch in ways that are not allowed by the Laws of Cricket. Because of this, coaches, players, commentators and pundits will make much of how the pitch is "behaving" during a cricket match, especially during a first class or a Test match that takes place over several days, wherein the condition of the pitch can change significantly over that period. These conditions will impact on the decision at the coin toss at the beginning of the game, as to whether batting first or bowling first is more advantageous. For example, a captain will prefer to bat first if the pitch is "flat" and presumably easier to bat on, but may be tempted to bowl first on a greener, more moist pitch that favours movement of the ball early.

In amateur matches in some parts of the world, artificial pitches are sometimes used. These can be a slab of concrete overlaid with a coir mat or artificial turf. Sometimes dirt is put over the coir mat to provide an authentic feeling pitch. Artificial pitches are rare in professional cricket, being used only when exhibition matches are played in regions where cricket is not a common sport.

The pitch has specific markings delineating the creases, as specified by the Laws of Cricket.

The word wicket often occurs in reference to the pitch. Although technically incorrect according to the Laws of Cricket (Law 6 covers the pitch and Law 8 the wickets, distinguishing between them), cricket players, followers, and commentators persist in the usage, with context eliminating any possible ambiguity. Track or deck are other synonyms for pitch.

The rectangular central area of the cricket field – the space used for pitches – is known as the square. Cricket pitches are usually oriented as close to the north-south direction as practical, because the low afternoon sun would be dangerous for a batter facing due west.

Uses of the pitch

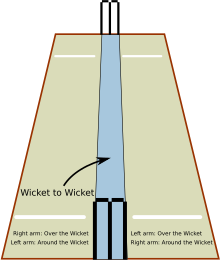

The pitch has one popping crease at each of its ends, with these dividing the field into the two batter's grounds, and the area in between (including the creases) in which the ball must be bowled and the batsmen run.

- Bowling: Bowlers can bowl the ball by throwing it and making it bounce on the ground of the pitch. The return creases, which follow almost directly from the edges of the pitch down the field, restrict the angle the bowler may bowl from.

- Batting: Batters may occasionally move around the pitch (particularly their crease in an effort to make contact with the ball). They may also make small marks on the pitch to indicate where they will stand, and while batting, they sometimes swing the bat in such a way that it hits some of the dirt in the pitch in the air.

- Running: The two batters may run along the sides of the pitch, between the batter's grounds, to score runs.

- Fielding: Occasionally fielders (often the bowler) may run on the pitch to run out a batter.

- Practice Session: Before a live cricket match, players have practice sessions with their official coach. They cannot use the main pitch, but are allowed to check the surface of the original pitch where the match will be played.

At any given moment, one end of the pitch will be the striker's end, while the other end is the non-striker's end. After each over, the ends swap. During the game, the bowler bowls from the nonstriker's end to the striker at the other end.

Protected area

The protected area or danger area is the central portion of the pitch – a rectangle running down the middle of the pitch, two feet wide, and beginning five feet from each popping crease. Under the Laws of Cricket, a bowler must avoid running on this area during their follow-through after delivering the ball.

The pitch is protected to preserve fairness in the game; the ball normally bounces on the pitch within this region, and if it is scuffed or damaged by the bowler's footmarks it can give an unfair advantage to the bowling side. These areas can be exploited by the bowlers to change the outcome of the match. If a bowler runs on the protected area, an umpire will issue a warning to the bowler and to their team captain. The umpire issues a second and final warning if the bowler transgresses again. On the third offence, the umpire will eject the bowler from the attack and the bowler may not bowl again for the remainder of the innings. The rule does not prevent the bowler or any other fielder from running on the protected area in an effort to field the ball; it applies only to the uninterrupted follow-through.

State of the pitch

A natural pitch with grass longer or more moist than usual is described as a green pitch, green top, or green seamer. This favours the bowler over the batter as the ball can be made to behave erratically on longer or wet grass. Most club and social cricket is played on pitches that professional cricketers would call green.

A sticky wicket – a pitch that has become wet and is subsequently drying out, often rapidly in hot sun – causes the ball to behave erratically, particularly for the slower or spin bowlers. However, modern pitches are generally protected from rain and dew before and during games so a sticky pitch is rarely seen in first-class cricket. The phrase, however, has retained currency and extended beyond cricket to mean any difficult situation.

As a match progresses, the pitch dries out. The Laws of Cricket bar watering the pitch during a match. As it dries out, initially batting becomes easier as any moisture disappears. Over the course of a four or five-day match, however, the pitch begins to crack, then crumble and become dusty. This kind of pitch is colloquially known as a 'dust bowl' or 'minefield'. This again favours bowlers, particularly spin bowlers who can obtain large amounts of traction on the surface and make the ball spin a long way. The relative deterioration and spin-friendliness of a pitch are often referred to by mentioning the number of days it has (or appears to have been) played on. A pitch which produces prodigious turn is referred to as a "Turner." When it produces a great deal of spin, it can be called a "square", "raging", or "rank" turner.

This change in the relative difficulties of batting and bowling as the state of the pitch changes during a match is one of the primary strategic considerations that the captain of the team that wins the coin toss will take into account when deciding which team will bat first and can accordingly finalise his decisions.

Pitch condition

Pitches in different parts of the world have different characteristics. The nature of the pitch plays an important role in the actual game: it may have a significant influence on team selection and other aspects. Pitches in hot and dry climates or seasons tend to have less grass on them, making batting easier. Batters or bowlers can have different levels of success based on the region they are in, and this is partially due to variation in pitches. As the pitch deteriorates throughout a match, this can also have considerable influence on the success or failure of a team's bowling or batting efforts.

Pitch safety

Certain conditions, as set out by the ICC, must be met to ensure that a pitch is fit and safe to play on. If the pitch is found to excessively favour one side, or if other conditions cause it to be dangerous, the match may, after agreement between the captains and the umpires, be abandoned and possibly rescheduled.

Preparation and maintenance of the playing area

See also: Turf managementLaw 9 of the Laws of Cricket sets out rules covering the preparation and maintenance of the playing area.

Uncovered pitches

Cricket was initially played on uncovered pitches. Uncovered pitches began to be phased out in the 1960s.

Covering the pitch

The pitch is said to be covered when the groundskeepers have placed covers on it to protect it against rain or dew. The use or non-use of covers significantly affects the way the ball comes off the pitch, making the matter potentially controversial. Law 11 of the Laws of Cricket provides that during the match the pitch shall not be completely covered unless provided otherwise by regulations or by agreement before the toss. When possible, the bowlers' run ups are covered in inclement weather to keep them dry. If the pitch is covered overnight, the covers are removed in the morning at the earliest possible moment on each day that play is expected to take place. If covers are used during the day as protection from inclement weather or if inclement weather delays the removal of overnight covers, they are removed as soon as conditions allow. Excess water can be removed from a pitch or the outfield using a machine called a water hog.

Rolling the pitch

During the match, the captain of the batting side may request the rolling of the pitch for a period of not more than 7 minutes before the start of each innings (other than the first innings of the match) and before the start of each subsequent day's play. In addition, if, after the toss and before the first innings of the match, the start is delayed, the captain of the batting side may request to have the pitch rolled for not more than 7 minutes, unless the umpires together agree that the delay has had no significant effect on the state of the pitch. Once the game has begun, rolling may not take place other than in these circumstances.

If there is more than one roller available, the captain of the batting side shall have the choice. Detailed rules exist to make sure that, where possible, rolling takes place without delaying the game but the game is delayed if necessary to allow the batting captain to have up to 7 minutes rolling if they so wish. Rolling the pitch can take a long time but will be very effective once done. Rolling of the pitch is crucial to whether it is better for a batter or a bowler.

For the 2010 County Championship season, the heavy roller was banned from use during a County Championship match. The belief was that the heavy roller was helping to make pitches flat, and therefore producing too many drawn games.

Sweeping

Before a pitch is rolled it is first swept to avoid any possible damage caused by rolling in debris. The pitch is also cleared of any debris at all intervals for meals, between innings and at the beginning of each day. The only exception to this is that the umpires do not allow sweeping to take place where they consider it may be detrimental to the surface of the pitch.

Mowing

Groundskeepers mow the pitch on each day of a match on which play is expected to take place. Once a game has begun, mowings take place under the supervision of the umpires.

Footholes and footholds

The umpires are required to make sure that bowlers' and batter's footholes are cleaned out and dried whenever necessary to facilitate play. In matches of more than one day's duration, if necessary, the footholes made by the bowler in his delivery stride may be returfed or covered with quick-setting fillings to make them safe and secure. Players may also secure their footholes using sawdust provided that the pitch is not damaged or they do not do so in a way that is unfair to the other team.

Research

England is the hub for considerable research in the preparation of cricket pitches, with Cranfield University working with the ECB and The Institute of Groundsmanship (IOG).

Practising on the field

The rules do not allow players to practise bowling or batting on the pitch, or on the area parallel and immediately adjacent to the pitch, at any time on any day of the match. Practice on a day of a match on any other part of the cricket square may take place only before the start of play or after the close of play on that day and must cease 30 minutes before the scheduled start of play or if detrimental to the surface of the square.

Typically players do practise on the field of play, but not on the cricket square, during the game. Also bowlers sometimes practise run ups during the game. However, no practice or trial run-up is permitted on the field of play during play if it could result in a waste of time. The rules concerning practice on the field are covered principally by Law 26 of the Laws of Cricket.

Typical pitches

Pitches in different parts of the world have different characteristics. The nature of the pitch plays an important role in the actual game: it may have a significant influence on team selection and other aspects. A spin bowler may be preferred in the Indian subcontinent where the dry pitches assist spinners (especially towards the end of a five-day test match) whereas an all pace attack may be used in places like Australia where the pitches are bouncy.

The nature of a pitch is determined more by the climatic and geographic conditions of that country. A few alterations could be done on the pitch such as weeding,watering and surfacing. However, it cannot completely change the characteristics of a pitch. And the nature of typical pitches prepared in a country seems to have an impact on the role played by the majority of the quality players it produces.

Pitches in England and Wales

Green, swing promoting and humid conditions sums up the construction of English pitches with a lot depending on the weather. Early in the season, most batsmen have to be on their guard as English pitches prove to be most fickle, like the country's weather. Later in the summer, the pitches tend to get harder and lose their green which makes the task easier for batsmen. Spinners prove less effective in the first half of the season and tend to play their part only in the second half. The dry and hot conditions and little dust makes the grounds ideal place to practise reverse swing with a 50-over old ball. England has mostly produced a lot of quality seam bowlers like Bob Willis, Ian Botham, James Anderson and many more who love to bowl in the good length areas of the pitch, since the pitches at their home ground supports a lot of lateral movement though it does not provide adequate bounce.

Pitches in Australia

Pitches in Australia have traditionally been known to be good for fast bowlers because of the amount of bounce that can be generated on these surfaces. The bounce is mainly generated because of the hardness of the pitches caused by the hot Australian summers and adequate moisture to reduce the cracks. In particular, the pitch at the WACA Ground in Perth is regarded as being possibly the quickest pitch in the world. The Gabba in Brisbane is also known to assist fast bowlers with its bounce. However, these kinds of bouncy pitches also open up more areas for run-scoring, as they promote the playing of a lot of pull, hook and cut shots. Batsmen who play these shots will have a lot of success on these pitches.

Other stadiums like Adelaide Oval and Sydney Cricket Ground have been known to assist spinners more as these pitches have more dust cover. This makes the stadiums an attractive ground for batsmen; teams on an average have scores of 300 or above in their first innings. The Melbourne Cricket Ground can assist seam bowlers initially, but it has a tennis-ball bounce which can negate the potency of bowlers once a match progresses.

Swing bowling can be a weapon in Australia, but unlike England, it depends upon the overhead conditions, similar to the Indian subcontinent. Australia has mostly produced a lot of legendary pace bowlers like Brett Lee, Mitchell Johnson, Glenn McGrath who love to bang the ball in short and have mastered the art of swing bowling, which is understood given the nature of their pitch.

Pitches in India

Pitches in India have historically supported spin bowling rather than seam or swing. A ball bowled at pace may not carry well to the keeper taking slip catches out of the equation. Such pitches had virtually no grass, afforded little assistance for pace, bounce, or lateral air movement, but created good turn due to the widened cracks. The main reason for such pitches is the hot and dry weather, which tends to remove the moisture from the pitches. In decades past, legendary spin bowlers – most notably the Indian spin quartet of the 1960s and 1970s, consisting of left-armer Bedi, offspinners Prasanna and Venkataraghavan, and legspinner Chandrasekhar – routinely toyed with visiting teams to plot dramatic victories for India in home test matches, particularly on turning pitches in hot, humid conditions at Eden Gardens in Kolkata (then known as Calcutta) and Chepauk in Chennai (then known as Madras).

They outwitted opposing batsmen not only through line, length, and trajectory variations but also by physically and psychologically exploiting rough spots resulting from wear and tear on the playing top and cracks from increasing surface dryness as a game progressed. The Indian batsmen, being accustomed to these pitch styles, generally relished home conditions. While the Brabourne and Wankhede stadiums in Mumbai and Ferozshah Kotla in Delhi never offered nearly as much turn to spinners.

Indian pitches and attitudes have changed considerably in the past few years though. The induction of several newer 'green top' venues (such as the ones at Mohali and at Dharamshala which have a cooler climate) provide English-like conditions, which has led to the emergence of Indian fast bowlers like Zaheer Khan, Javagal Srinath, Ashish Nehra, RP Singh and many more in the recent past who have mastered swing bowling and usually bowl at English-like length, which is the good length areas . The development of domestic league cricket with international participants in the form of IPL, Ranji Trophy, ICL, have resulted in a greater variety of pitches. Some contemporary pitches provide good support for pace, bounce, and swing. Surfaces are often tailor made to be flat tops or excessively batsmen-friendly by surfacing the pitch really well, for the sake of maximising entertainment value, at the expense of all types of bowlers. But at time the reverse is true especially in the IPL wherein pace heavy teams often come-up with green pace friendly pitches to maximise chances of victory.

Pitches in South Africa

Pitches resemble those in Australia with added swing (lateral) movement and comparatively lesser bounce. However, genuine fast bowlers who can hit the deck hard and hope for some seam as well do the most damage. Spinners gain little assistance, as in New Zealand, and have to toil hard. The reason for these kind of pitches is again the same as that in Australia, that is hot summers with adequate moisture. South Africa is known to produce quality fast bowlers like Dale Steyn, Shaun Pollock, Kagiso Rabada and many more.

Pitches in New Zealand

Pitches in New Zealand, like the ones at Eden Park, Auckland and Basin Reserve, Wellington can have a green tinge similar to their counterparts in England. The ball swings a lot due to the proximity of most grounds to the sea, relative humidity and moisture under the surface. New Zealand pitches are often bouncy and quick in nature due to the usual grass cover left on them. The grass cover offers seam movement early on, but also maintains the integrity of the pitch which can often dampen the effect of spin bowling but allows pitches to flatten out over the course of a match. Batting can be trying early on and batsman often take time to adjust to the conditions. New Zealand is known to produce quality fast bowlers like Danny Morrison, Tim Southee, Trent Boult, Sir Richard Hadlee and many more.

Pitches in the West Indies

The West Indies tends to produce balanced pitches. Neither is the bounce too disconcerting nor is the movement extravagant. It also does not assist spin like subcontinent pitches and hence for quality batsman they could be batting paradises. However, bowlers who are willing to bend their backs find some assistance from these pitches. Pitches here have earned a reputation of helping the quicks somewhat mainly because of the era gone by when West Indies used to have some of the fastest bowlers in cricket and hence the pitches appeared to be faster than they are. Tall bowlers like Malcolm Marshall, Joel Garner, Michael Holding, Andy Roberts, Ian Bishop, Colin Croft, Curtly Ambrose and Courtney Walsh produced bounce and speed even on the most docile pitches. However, some of the best batsmen have arisen from the Caribbean too, like Viv Richards, Gary Sobers, Desmond Haynes, George Headley, Clive Lloyd, Shivnarine Chanderpaul, Rohan Kanhai, Chris Gayle and Brian Lara. Spinners also have something in the pitches as they tend to deteriorate by day four, offering a little dust and cracks for them to exploit. But due to insufficient support to spin in the Caribbean pitches, West Indies has not produced many all-time great spinners with the exception of Lance Gibbs.

Pitches in Pakistan

Pitches in Pakistan have historically supported spin bowling rather than seam or swing. However, the conditions in most grounds of Pakistan, like Rawalpindi, Lahore and Peshawar have also seen support for the reverse swing capabilities of bowlers in past times. The dry and windy conditions usually lend good support to the faster bowlers as well. Such pitches had virtually no grass, afforded little assistance for pace, bounce, or lateral air movement, but created good turn. In decades past spinners toyed with visiting teams to plot dramatic victories for Pakistan in home test matches, particularly on turning pitches in hot, humid conditions at Arbab Niaz Stadium and Gaddafi Stadium. Pitches in Pakistan are flat and considered favourable for batsmen in winter; they suit spinners in summers. Pakistan has produced quality spin bowlers like Shaqlain Mushtaq, Saeed Ajmal, Mushtaq Ahmed as well as pace bowlers who have mastered the art of late swing and reverse swing including the likes of Waqar Younis, Wasim Akram and many more.

Pitches in Bangladesh

The Bangladeshi wickets receive a lot of rain fall in little time which reflects the soggy nature. The conditions vary from grounds like Sher-e-Bangla Cricket Stadium and Chittagong Divisional Stadium. The basic idea of producing wickets in Bangladesh is to avoid using grassroots when they are building up the layers of soil. The roots hold the water and retain moisture for an extended period. It helps bind the wicket better, making it a harder surface eventually. It also slows the process of wearing down.

Pitches in Sri Lanka

Pitches are generally dusty and shorn off grass; the rain here also makes for a "sticky wicket". Wickets are generally flat and don't offer much bounce – however, the pitch at Asgiriya Stadium, Kandy offers generous bounce and favours fast bowling. Bowlers get help under the lights. Spin is the key in these conditions, and spinners have fine records on the pitches in Sri Lanka. The heat requires an extreme level of fitness, while sweaty clothing makes it difficult to shine the ball. Apart from off-spin and leg-spin, reverse swing is also an effective tools in such conditions. This could be a good explanation Sri Lanka has produced a lot of quality spin bowlers like Muttiah Muralidharan, Rangana Herath and their likes as well as quality pace bowlers like Chaminda Vaas, Lasith Malinga and many more.

Pitches in Zimbabwe

Pitches in Zimbabwe closely resemble those in South Africa with the main difference being in the nature of the bounce. The pitches in South Africa provide fast bounce while the pitches in Zimbabwe tend to have a spongy, tennis ball type of bounce, which makes hitting on the up a risky proposition. Most pitches have slower bounce, hence batting is more favourable in Zimbabwe.

Conditions at the Queens Sports Club, Bulawayo tend to aid batsmen, with spin coming into the game in a big way in the latter stages. The pitch has some grass, though not green enough to leave batsmen anxious. With the temperature touching 28 degrees, the strip is expected to dry out quickly and flatten into a batting beauty. The seamers' best chance will be with the new ball, and both teams feel keen to make first use of the pitch.

Pitches in UAE

The UAE features spin-friendly pitches, which is understood given its hot dry weather. New ball helps the bowlers and bowlers eye reverse swing and spin with the older ball. UAE conditions differ significantly from those of Pakistan due to the Gulf's sandy soils. Grounds are not that hard. Dubai Cricket Stadium offers some grass and bounce though dry conditions tend to result in the fourth and fifth days of a Test match being spin friendly. Sheikh Zayed Stadium is batting-friendly, and the cracks come very late into play.

Drop-in pitches

A drop-in pitch is a pitch that is prepared away from the ground or venue in which it is used, and "dropped" into place for a match to take place. This allows multi-purpose venues to host other sports and events with more versatility than a dedicated cricket ground would allow. Much like an integral pitch, a quality drop-in pitch takes several years to cultivate, grounds would maintain and utilise each drop-in pitch over multiple seasons, and pitches can deteriorate over many years to the point that they need to be retired.

They were first developed by WACA curator John Maley for use in the World Series Cricket matches, set up in the 1970s by Australian businessman Kerry Packer. Drop-in pitches became necessary for the World Series as they had to play in dual purpose venues operating outside of the cricket establishment. Along with other revolutions during the series including the white ball, floodlights, helmets, and coloured clothing, drop-in pitches were designed to also make games more interesting. They would start off bowler friendly seaming and spinning with uneven bounce for the first two days of a game. After that they became extremely easy for batting meaning high targets were chaseable on the fourth and fifth days, although there would still be something in the pitch for the bowlers.

In 2005, the Brisbane Cricket Ground (the "Gabba") rejected the use of a drop-in pitch, despite requests from the ground's other users, the Brisbane Lions AFL team. Although drop-in pitches are regularly used in the Melbourne Cricket Ground and in New Zealand, Queensland Cricket stated that Brisbane's weather and the difference in performance meant they preferred to prepare the ground in the traditional way.

Plans to use drop-in pitches in baseball parks in the United States have met with problems due to strict rules about transporting soil over American state lines. It has been found that the best soil types for drop-in pitches are not located in the same states which have been targeted by cricketing authorities – New York, California and Florida.

Related usages

The word pitch also refers to the bouncing of the ball, usually on the pitch. In this context, the ball is said to pitch before it reaches the batter. Where the ball pitches can be qualified as pitched short (bouncing nearer the bowler), pitched up (nearer the batter), or pitched on a length (somewhere in between).

Unlike in baseball, the word pitch does not refer to the act of propelling the ball towards the batter in cricket. In cricket this is referred to as bowling. This action is also referred to as a delivery.

Other sports

In baseball, some baseball fields used to have a dirt path between the pitcher's mound and the batter's box, similar to the pitch.

References

- "The measurements of cricket". ESPN Cricinfo. Retrieved 19 February 2020.

- "Different types of pitch in cricket - Dusty, Dead, Green". CRICK ACADEMY. 12 November 2018. Retrieved 18 June 2019.

- "County Championship - Points System". static.espncricinfo.com. Retrieved 18 June 2019.

- Nagraj, Gollapudi. "Luckless Windies show bottle after bold decision to bowl first". CricInfo.

- "The flattest ODI pitch in the world". www.espncricinfo.com. Retrieved 11 September 2020.

- Pierik, Jon (28 February 2019). "Fresh pitch: MCG to have new deck for Boxing Day Test". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 11 September 2020.

- "Orientation of outdoor playing areas". Government of Western Australia, Department of Sport and Recreation. 7 August 2013. Retrieved 11 April 2014.

- "Zampa's unbelievable run out". YouTube. 9 January 2016.

- "Law 41 – Unfair play". Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- "What is cricket's 'protected area'?". News.bbc.co.uk. 25 August 2005. Retrieved 16 June 2019.

- Barrett, Chris (8 December 2015). "Hobart pitch first look reveals green seamer for Australia v West Indies test". Stuff.co.nz.

- ^ "A List of Technical Cricket Terms". Retrieved 8 January 2015.

- "India vs Australia, 2nd Test: Bengaluru pitch to be a 'slow turner'?". Deccan Chronicle. 28 February 2017. Retrieved 31 August 2020.

- "Different Types Of Cricket Pitches Around The World". theneptunesports.com. 19 February 2021. Retrieved 22 December 2022.

- "The guidelines for rating a pitch 'dangerous' or 'unfit'". Cricbuzz. 26 January 2018. Retrieved 26 January 2018.

- "Cricket's Turning Points: Covered pitches | Highlights". Cricinfo Magazine. ESPN Cricinfo. Retrieved 1 September 2013.

- "Heavy rollers banned in English county". Archived from the original on 17 January 2015. Retrieved 8 January 2015.

- "Guidelines for Rolling in Cricket". Cranfield's Centre for Sports Surface Technology / England and Wales Cricket Board. Archived from the original on 29 September 2012. Retrieved 26 February 2013.

- "Why do cricket pitches in different countries have different qualities? - Quora". www.quora.com. Retrieved 13 December 2018.

- "Teams try to adapt strategies to low, slow track" ESPN. Retrieved 1 December 2013.

- "Ranasinghe Premadasa Stadium Colombo, Cricket, Features of Ranasinghe Premadasa Stadium Colombo, History of Ranasinghe Premadasa Stadium Colombo, Popularity of Ranasinghe Premadasa Stadium Colombo, Tournaments". Livescore.warofcricket.com. Archived from the original on 10 March 2012. Retrieved 1 September 2013.

- "Zimbabwe v Pakistan, only Test, Bulawayo: Another baby step into the wild for Zimbabwe". ESPN Cricinfo. 31 August 2011. Retrieved 1 September 2013.

- Gollapudi, Nagraj: "Pitch drops in at Darwin", CricInfo Australia, July 17, 2003.

- MCG on notice after ICC rates pitch 'poor', By Andrew Ramsey, 2 January 2018, cricket.com.au

- Jon Pierik (23 December 2020). "'Significant change': MCG pitch to be upgraded". The Age. Melbourne, VIC. Retrieved 13 March 2021.

- Pringle, Derek: "Packer's gamble left lasting legacy", The Daily Telegraph, December 28, 2005.

- "Queensland reject drop-in pitch for Gabba", CricInfo Australia, August 22, 2005.

- "Stillborn in the USA", Cricinfo Australia, January 23, 2007

- Neyer, Rob (4 October 2011). "So What's The Deal With Those Dirt Strips?". SBNation.com. Retrieved 2 September 2020.