This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

A nonlinear dispersion relation (NDR) is a dispersion relation that assigns the correct phase velocity to a nonlinear wave structure. As an example of how diverse and intricate the underlying description can be, we deal with plane electrostatic wave structures which propagate with in a collisionless plasma. Such structures are ubiquitous, for example in the magnetosphere of the Earth, in fusion reactors, or in a laboratory setting. Correct means that this must be done according to the governing equations, in this case the Vlasov-Poisson system, and the conditions prevailing in the plasma during the wave formation process. This means that special attention must be paid to the particle trapping processes acting on the resonant electrons and ions, which requires phase space analyses. Since the latter is stochastic, transient and rather filamentary in nature, the entire dynamic trapping process eludes mathematical treatment, so that it can be adequately taken into account “only” in the asymptotic, quiet regime of wave generation, when the structure is close to equilibrium.

This is where the pseudo-potential method in the version of Schamel, also known as Schamel method, comes into play, which is an alternative to the method described by Bernstein, Greene and Kruskal. In the Schamel method the Vlasov equations for the species involved are first solved and only in the second step Poisson's equation to ensure self-consistency. The Schamel method is generally considered the preferred method because it is best suited to describing the immense diversity of electrostatic structures, including their phase velocities. These structures are also known under Bernstein–Greene–Kruskal modes or phase space electron and ion holes, or double layers, respectively. With the S method, the distribution functions for electrons and ions , which solve the corresponding time-independent Vlasov equation,

and , respectively,

are described as functions of the constants of motion. Thereby the unperturbed plasma conditions are adequately taken into account. Here and are the single particle energies of electrons and ions, respectively ; and are the signs of the velocity of untrapped electrons and ions, respectively. Normalized quantities have been used, and it is assumed that , where is the amplitude of the structure.

Of particular interest is the range in phase space where particles are trapped in the potential wave trough. This area is (partially) filled via the stochastic particle dynamics during the previous creation process and is expressed and parameterized by so-called trapping scenarios.

In the second step, Poisson's equation, , where are the corresponding densities obtained by velocity integration of and , is integrated whereby the pseudo-potential is introduced. The result is , which represents the pseudo-energy. In the points stand for the different trapping parameters . Integration of the pseudo-energy results in , which yields by inversion the desired . In these expressions the canonical form of is used already.

There are, however, two further trapping parameters , which are missing in the canonical pseudo-potential. In its extended previous version they fell victim to the necessary constraint that the gradient of the potential vanishes at its maximum. This requirement is

and leads to the term in question, the nonlinear dispersion relation (NDR). It allows the phase speed of the structure to be determined in terms of the other parameters and to eliminate from to obtain the canonical . Due to the central role, the two expressions and are playing, the Schamel method is sometimes also called Schamel's pseudo-potential method (SPP method). For more information, see references 1 and 2.

A typical example for the canonical pseudo-potential and the NDR is given by

and by

where and , respectively.

These expressions are valid for a current-carrying, thermal background plasma described by Maxwellians (with a drift between electrons and ions) and for the presence of the perturbative trapping scenarios , s=e,i.

A well known example is the Thumb-Teardrop dispersion relation, which is valid for single harmonic waves and is given as a simplified version of the NDR above with zero trapping parameters and a vanishing drift. It reads

.

It has been thoroughly discussed in but mistakenly as a linear dispersion relation.

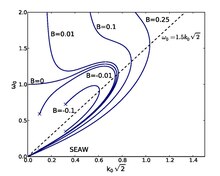

A plot of for a more general type of structures, the periodic cnoidal electron holes, is presented in Fig 1. for the case and immobile ions () showing the effect of the electron trapping parameter for positive and negative values.

Finally, it should be mentioned that an NDR has the nice property that it remains valid even if the potential has an undisclosed form, i.e. can no longer be described by mathematically known functions.

References

- ^ Schamel, H. (2023). "Pattern formation in Vlasov–Poisson plasmas beyond Landau caused by the continuous spectra of electron and ion hole equilibria". Reviews of Modern Plasma Physics. 7 (1): 11. arXiv:2110.01433. Bibcode:2023RvMPP...7...11S. doi:10.1007/s41614-022-00109-w. ISSN 2367-3192.

- ^ Schamel, H. (1972). "Stationary solitary, snoidal and sinusoidal ion acoustic waves". Plasma Physics. 14 (10): 905. Bibcode:1972PlPh...14..905S. doi:10.1088/0032-1028/14/10/002.

- Bernstein, Ira B.; Greene, John M.; Kruskal, Martin D. (1957). "Exact Nonlinear Plasma Oscillations". Physical Review. 108 (3): 546–550. Bibcode:1957PhRv..108..546B. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.108.546. hdl:2027/mdp.39015095115203.

- Trivedi, Pallavi; Ganesh, Rajaraman (2018). "Symmetry in electron and ion dispersion in 1D Vlasov-Poisson plasma". Physics of Plasmas. 25: 112102. doi:10.1063/1.50052494 (inactive 1 November 2024).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) - Schamel, Hans (2019). "Comment on "Symmetry in electron and ion dispersion in 1D Vlasov-Poisson plasma"". Physics of Plasmas. 26: 064701. doi:10.1063/1.5090595.

- Schamel, Hans (2012). "Cnoidal electron hole propagation: Trapping,the forgotten nonlinearity in plasma and fluid dynamics". Physics of Plasmas. 19 (2): 020501. Bibcode:2012PhPl...19b0501S. doi:10.1063/1.3682047.

to a nonlinear wave structure.

As an example of how diverse and intricate the underlying description can be, we deal with plane

to a nonlinear wave structure.

As an example of how diverse and intricate the underlying description can be, we deal with plane  which propagate with

which propagate with  and ions

and ions  , which solve the corresponding time-independent Vlasov equation,

, which solve the corresponding time-independent Vlasov equation,

and

and  , respectively,

, respectively,

and

and

are the single particle energies of electrons and ions, respectively ;

are the single particle energies of electrons and ions, respectively ;  and

and  are the signs of the velocity of untrapped electrons and ions, respectively. Normalized quantities have been used,

are the signs of the velocity of untrapped electrons and ions, respectively. Normalized quantities have been used,  and it is assumed that

and it is assumed that  , where

, where  is the amplitude of the structure.

is the amplitude of the structure.

, where

, where  are the corresponding densities obtained by velocity integration of

are the corresponding densities obtained by velocity integration of  and

and  , is integrated whereby the pseudo-potential

, is integrated whereby the pseudo-potential  is introduced. The result is

is introduced. The result is  , which represents the pseudo-energy. In

, which represents the pseudo-energy. In

. Integration of the pseudo-energy results in

. Integration of the pseudo-energy results in  , which yields by inversion the desired

, which yields by inversion the desired  . In these expressions the canonical form of

. In these expressions the canonical form of  , which are missing in the canonical pseudo-potential. In its extended previous version

, which are missing in the canonical pseudo-potential. In its extended previous version  they fell victim to the necessary constraint that the gradient of the potential

they fell victim to the necessary constraint that the gradient of the potential

and

and  , respectively.

, respectively.

between electrons and ions) and for the presence of the perturbative trapping scenarios

between electrons and ions) and for the presence of the perturbative trapping scenarios  , s=e,i.

, s=e,i.

.

.

for a more general type of structures, the periodic cnoidal electron holes, is presented in Fig 1. for the case

for a more general type of structures, the periodic cnoidal electron holes, is presented in Fig 1. for the case  and immobile ions (

and immobile ions ( ) showing the effect of the electron trapping parameter

) showing the effect of the electron trapping parameter  for positive and negative values.

for positive and negative values.