In economics, a normal good is a type of a good which experiences an increase in demand due to an increase in income, unlike inferior goods, for which the opposite is observed. When there is an increase in a person's income, for example due to a wage rise, a good for which the demand rises due to the wage increase, is referred as a normal good. Conversely, the demand for normal goods declines when the income decreases, for example due to a wage decrease or layoffs.

Analysis

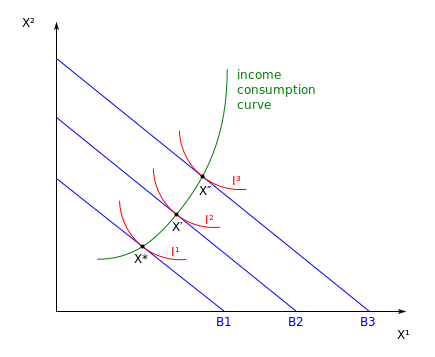

There is a positive correlation between the income and demand for normal goods, that is, the changes income and demand for normal goods moves in the same direction. That is to say, that normal goods have an elastic relationship for the demand of a good with the income of the person consuming the good.

In economics, the concept of elasticity, and specifically income elasticity of demand is key to explain the concept of normal goods. Income elasticity of demand measures the magnitude of the change in demand for a good in response to a change in consumer income. the income elasticity of demand is calculated using the following formula,

Income elasticity of demand= % change in quantity demanded / % change in consumer income.

In mathematical terms, the formula can be written as follows:

, where is the original quantity demanded and is the original income, before any change.

A good is classified as a normal good when the income elasticity of demand is greater than zero and has a value less than one. If we look into a simple hypothetical example, the demand for apples increases by 10% for a 30% increase in income, then the income elasticity for apples would be 0.33 and hence apples are considered to be a normal good. Other types of goods like luxury and inferior goods are also classified using the income elasticity of demand. The income elasticity of demand for luxury goods will have a value of greater than one and inferior goods will have a value of less than one. Luxury goods also have a positive correlation of demand and income, but with luxury goods, a greater proportion of peoples income are spent on a luxury item, for example, a sports car. On the other hand, with inferior or normal goods, people spend a lesser proportion of their income. Practically, a higher income group of people spend more on luxury items and a lower income group of people spend more of their income on inferior or normal goods.

However, the classification of normal and luxury goods vary from person to person. A good that is considered to be a normal good to a lot of people maybe considered to be luxury good to someone. This depends on a lot of factors such as geographical locations, socio economic conditions in a country, local traditions and many more.

Normal goods and consumer behaviour

The demand for normal goods are determined by many types of consumer behaviour. A rise in income leads to a change in consumer behaviour. When income increases, consumers are able to afford goods that they could not consume before an income rise. The purchasing power of consumers increases. In this situation, the demand rises because of the attractiveness to consumers. The goods are attractive to the consumers maybe because they are high in quality and functionality and also the goods may help to maintain a certain socio economic prestige. Individual consumers have unique behavioural characteristics and they have their preferences accordingly.

According to economic theory, there must be at least one normal good in any given bundle of goods (i.e. not all goods can be inferior). Economic theory assumes that a good always provides marginal utility (holding everything else equal). Therefore, if consumption of all goods decrease when income increases, the resulting consumption combination would fall short of the new budget constraint frontier. This would violate the economic rationality assumption.

When the price of a normal good is zero, the demand is infinite.

Examples

| Category | Normal good | Inferior good |

|---|---|---|

| Food and drink |

|

|

| Transportation |

|

|

| Other |

|

|

A caveat to the table above is that not all goods are strictly normal or inferior across all income levels. For example, average used cars could have a positive income elasticity of demand at low income levels – extra income could be funnelled into replacing public transportation with self-commuting. However, the income elasticity of demand of average used cars could turn negative at higher income levels, where the consumer may elect to purchase new and/or luxury cars instead.

Another potential caveat is brought up by "The Notion of Inferior Good in the Public Economy" by Professor Jurion of University of Liège (published 1978). Public goods such as online news are often considered inferior goods. However, the conventional distinction between inferior and normal goods may be blurry for public goods. (At least, for goods that are non-rival enough that they are conventionally understood as "public goods.") Consumption of many public goods will decrease when a rational consumer's income rises, due to replacement by private goods, e.g. building a private garden to replace use of public parks. But when effective congestion costs to a consumer rises with the consumer's income, even a normal good with a low income elasticity of demand (independent of the congestion costs associated with the non-excludable nature of the good) will exhibit the same effect. This makes it difficult to distinguish inferior public goods from normal ones.

See also

References

- ^ Perloff, Jeffrey M. (2015). Microeconomics (Seventh ed.). Boston. ISBN 978-0133456912. OCLC 876140973.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Investopedia Staff (2007-06-21). "Normal Good". Investopedia. Retrieved 2018-03-06.

- "Inferior Good – Full Explanation & Example | InvestingAnswers". www.investinganswers.com. Retrieved 2018-03-06.

- ^ Pettinger, Tejvan. "Different types of goods - Inferior, Normal, Luxury". Economics Help. Retrieved 2020-11-01.

- ^ "Normal Goods - Definition, Graphical Representation and Examples". Corporate Finance Institute. Retrieved 2020-11-01.

- "Today in classism". The Economist. 2008-05-27. Retrieved 2018-03-06.

- Chyi, Hsiang Iris (Autumn 2009). "Is Online News an Inferior Good? Examining the Economic Nature of Online News among Users". Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly. 86 (3): 592–612. doi:10.1177/107769900908600309. S2CID 145068946.

- Jurion, B.J. (January 3, 1978). "The Notion of Inferior Good in Public Economy". Annals of Public and Cooperative Economics. 49: 79–101. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8292.1978.tb01763.x.

Category:

, where

, where  is the original quantity demanded and

is the original quantity demanded and  is the original income, before any change.

is the original income, before any change.