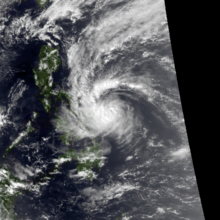

Thelma near peak intensity, approaching the Philippines on November 4 Thelma near peak intensity, approaching the Philippines on November 4 | |

| Meteorological history | |

|---|---|

| Formed | November 1, 1991 |

| Dissipated | November 8, 1991 |

| Tropical storm | |

| 10-minute sustained (JMA) | |

| Highest winds | 75 km/h (45 mph) |

| Lowest pressure | 992 hPa (mbar); 29.29 inHg |

| Tropical storm | |

| 1-minute sustained (SSHWS/JTWC) | |

| Highest winds | 85 km/h (50 mph) |

| Overall effects | |

| Fatalities | 5,081 – 8,165 total (4,922 in Ormoc) |

| Damage | $27.7 million (1991 USD) |

| Areas affected | |

| IBTrACS | |

Part of the 1991 Pacific typhoon season | |

Tropical Storm Thelma, known in the Philippines as Tropical Storm Uring, was one of the deadliest tropical cyclones in Philippine history, killing at least 5,081 people. Forming out of a tropical disturbance on November 1, 1991, several hundred kilometers north-northeast of Palau, the depression that would become Thelma tracked generally westward. After turning southwestward in response to a cold front, the system intensified into a tropical storm on November 4 as it approached the Philippines. Hours before moving over the Visayas, Thelma attained its peak intensity with estimated ten-minute sustained winds of 75 km/h (45 mph) and a barometric pressure of 992 mbar (hPa; 29.29 inHg). Despite moving over land, the system weakened only slightly, emerging over the South China Sea on November 6 while retaining gale-force winds. Thelma ultimately succumbed to wind shear and degraded to a tropical depression. On November 8, the depression made landfall in Southern Vietnam before dissipating hours later.

While passing over the Philippines, Thelma's interaction with the high terrain of some of the islands resulted in torrential rainfall. Through the process of orographic lift, much of the Visayas received 150 mm (6 in) of rain; however, on Leyte Island there was a localized downpour that brought totals to 580.5 mm (22.85 in). With the majority of this falling in a three-hour span, an unprecedented flash flood took place on the island. Much of the land had been deforestated or poorly cultivated and was unable to absorb most of the rain, creating a large runoff. This water overwhelmed the Anilao–Malbasag watershed and rushed downstream. Ormoc City, located past where the Anilao and Malbasag rivers converge, suffered the brunt of the flood. In just three hours, the city was devastated with thousands of homes damaged or destroyed. A total of 4,922 people were killed in the city alone, with 2,300 perishing along the riverbank.

Outside of Ormoc City, 159 people were killed across Leyte and Negros Occidental. Throughout the country, at least 5,081 people died while another 1,941–3,084 were missing and presumed dead. This made Thelma the deadliest tropical cyclone in Philippine history, surpassing a storm in 1867 that killed 1,800, until later surpassed by Typhoon Haiyan (Yolanda) in 2013 which killed at least 6,300 people. A total of 4,446 homes were destroyed while another 22,229 were damaged. Total losses amounted to $27.67 million. Initially, it took over 24 hours for word of the disaster to reach officials due to a crippled communication network around Ormoc City. Within a few days, emergency supply centers were established and aid from various agencies under the United Nations and several countries flowed into the country. A total of $5.8 million worth of grants and materials was provided collectively in the international relief effort.

Meteorological history

Map key Saffir–Simpson scale Tropical depression (≤38 mph, ≤62 km/h)

Tropical storm (39–73 mph, 63–118 km/h)

Category 1 (74–95 mph, 119–153 km/h)

Category 2 (96–110 mph, 154–177 km/h)

Category 3 (111–129 mph, 178–208 km/h)

Category 4 (130–156 mph, 209–251 km/h)

Category 5 (≥157 mph, ≥252 km/h)

Unknown Storm type

Tropical cyclone

Tropical cyclone  Subtropical cyclone

Subtropical cyclone  Extratropical cyclone, remnant low, tropical disturbance, or monsoon depression

Extratropical cyclone, remnant low, tropical disturbance, or monsoon depression In late October 1991, a tropical disturbance developed near the Caroline Islands. Tracking generally west-northwestward, the system gradually became more defined. On October 31, convection associated with the system quickly increased, prompting the issuance of a Tropical Cyclone Formation Alert from the Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC). Early on November 1, the Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA) began monitoring the system as a tropical depression, at which time the system was situated roughly 415 km (258 mi) north-northeast of Palau. Following a satellite-derived surface wind estimate of 45 km/h (30 mph) later that day, the JTWC also began monitoring the low as a tropical depression. Initially, forecast models showed the system continuing on an arcing path out to sea; however, the system turned westward on November 2 and threatened the Philippines. Due to the cyclone's proximity to the country, the Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration also monitored the storm and assigned it with the local name Uring. Late on November 3, the depression turned west-southwestward towards the Visayas in response to an approaching cold front, an event typical of late-season cyclones in the basin. On November 4, both the JTWC and JMA upgraded the system to a tropical storm, with the former assigning it as Thelma.

Hours before striking the Philippines on November 4, both agencies reported Thelma to have reached its peak intensity. The JTWC estimated the storm to have attained one-minute sustained winds of 85 km/h (55 mph) while the JMA estimated ten-minute sustained winds at 75 km/h (45 mph). Additionally, its barometric pressure reached 992 mbar (hPa; 29.29 inHg). Thelma soon made landfall in Samar before weakening to a minimal tropical storm. Maintaining gale-force winds, the system eventually passed over Palawan Island on November 6 before moving over the South China Sea. Despite being back over water, strong wind shear prevented re-intensification and caused Thelma to weaken to a tropical depression by November 7. Now moving westward, the depression eventually made its final landfall over the Mekong River Delta in Southern Vietnam on November 8. Over the next couple of days the system weakened into an area of low pressure as it moved westwards, before it moved into the Andaman Sea during November 10. Once in the Andaman Sea, the systems remnants contributed to the formation of the Karaikal tropical cyclone during the next day.

Impact

Tropical Storm Thelma struck the Philippines just five months after the Ultra-Plinian eruption of Mount Pinatubo. The eruption resulted in the deaths of roughly 800 people and left nearly 1 million homeless. The country's government was reportedly struggling to deal with the scope of the disaster and the addition of Thelma worsened the situation.

Striking the nation as a weak tropical storm, winds from Thelma gusted up to 95 km/h (60 mph) in Tacloban; these winds caused no known damage. The main destructive force associated with the cyclone was the tremendous rainfall it produced. More than 150 mm (6 in) of rain across much of the Visayas, resulting in widespread flooding. In Tacloban, 140.2 mm (5.52 in) fell over a 24‑hour span. The heaviest rain occurred on Leyte Island due to orographic lift, which brought large quantities of moisture into the atmosphere over a relatively small area. Additionally, monsoonal winds to the southwest of Thelma converged over the island, further enhancing the precipitation. Near the city of Ormoc, a Philippine National Oil Company rain gauge measured 580.5 mm (22.85 in) of precipitation, the highest in relation to the storm. Of this, approximately 500 mm (20 in) fell during a three-hour span around noon local time on November 5. Initially, residents believed that waterspouts transported tremendous amounts of water to the island, triggering the floods. This notion was quickly dismissed as improbable, however.

The hardest hit region was Leyte, where more than 4,000 people died. A total of 4,446 homes were destroyed while another 22,229 were damaged. The majority of casualties and damage took place in Ormoc when a flash flood devastated the city. At least 81 people were killed outside Ormoc and another 14 went missing; 42 died in Burauen. The entire island of Leyte was left without power and many areas were isolated as roads were washed away. Another 78 people perished and 70 others were left missing in Negros Occidental. Losses from the storm amounted to $27.67 million; $18.94 million in Leyte and $8.73 million in Negros Occidental. A total of 598,454 people were affected while an estimated 43,000 people were left homeless by the storm across the Philippines.

Ormoc City

Tropical Storm Thelma devastated the city of Ormoc after torrential rains overwhelmed the Anilao–Malbasag watershed, sending flood waters rushing down the deforested mountainside. This water flowed into the Anilao and Malbasag rivers, located north of Ormoc. The watershed, covering an area of 4,567 hectares (11,285 acres), is only 3.3 percent forested, with the remainder being used for agricultural and private purposes. According to a study in 1990, roughly 90 percent of the watershed had been converted into coconut and sugarcane plantations. The majority of this land was improperly cultivated since the 1970s, making conditions worse than they normally would have been. The morphology of the mountains further contributed to the floods, with slopes as steep as 60 percent grade in some areas. In heavy rain events, this feature leaves the upper two-thirds of the mountain range unstable. In the two hours prior to the heaviest rains, the soil in the watershed became saturated, greatly lessening its effectiveness at absorbing further rains. As a result, the tremendous rains that occurred just prior to the flood, during which rainfall rates reached 167 mm (6.6 in) per hour, the land was unable to absorb a majority of the rain. Many landslides ranging from 1 to 3 m (3.3 to 9.8 ft) deep and 50 to 100 m (160 to 330 ft) wide occurred across the region. Altogether, rains were twice as heavy as the land could handle and the many landslips doubled the volume of fluids. At various points along rivers, temporary dams created by debris, namely trees, allowed a build up of water upstream. In some instances, waters reached a depth of 10 m (33 ft) before the dams collapsed. Normally, it takes water in the Anilao and Malbasag rivers roughly 3.6 and 5.6 days, respectively, to reach Ormoc City; however, it only took one hour during the flood.

Ormoc City is located in a flood-prone area, with the Anilao and Malbasag rivers converging just north of the city and taking a 90-degree turn towards the bay. In addition to the natural dangers of the river, poorly designed structures on the river made conditions worse. The majority of construction along the river did not take flooding threats into account, and actually increased the threat of these events. Concrete walls and levees were built into the river rather than on the banks, leading to faster debris damming. Lastly, just after the turn was the Cogon Bridge. This structure constricted the river by as much as 50 percent, enhancing the build up of water. The turn became the final trigger in the disaster as it created an "instantaneous backwater effect," causing massive volumes of water to over-top the riverbank. Around 11:00 a.m. local time on November 5, approximately 22,835 km (5,478 cu mi) of water inundated 25 km (9.7 sq mi) of the city. In just 15 minutes, the water rose by 2.1 m (7 ft) and further rose to 3.7 m (12 ft) within an hour. The flooding lasted for roughly three hours, leaving up to 0.6 m (2.0 ft) of sediment behind.

Survivor from Isle Verde"The waters kept rising. We had to place our children on top of the refrigerator. Still, the waters kept going up so we all had to climb to the roof. But perhaps we are bless. We all survived."

The flood struck the city with little to no warning, catching all those in its path off-guard. Numerous low-income families lived along the banks of the river, despite being such a high-risk area. Residential and commercial areas were also set up along reclaimed embankments that restricted river flow. Additionally, squatters were allowed to live along the banks of the Anilao river in an area called Isle Verde. Roughly 2,500 people lived on this reclaimed land prior to the flood. The majority of fatalities took place along the banks of the river, with most drowning or being buried in mud or debris. A survivor described the initial event as a gigantic wave crashing over the banks and flooding the city. Isle Verde was virtually wiped out and out of the original 2,500 people that lived there, only 200 survived. It became known as the "Isle of Death" to survivors. Residents reported hundreds of bodies floating down rivers in the area. The force of the water and mud was enough to crack the walls of city hall. Nearly 3,000 homes were destroyed and more than 11,000 others were damaged. In the city alone, officials confirmed that 4,922 people were killed and another 1,857–3,000 were left missing. Additionally, 3,020 people were injured. The majority of those missing were likely swept out to sea by the flood and presumed dead. Two days after the storm, several bodies of those swept out to sea washed back ashore. Officials stated that the death toll could have been in the tens of thousands had the flood occurred at night rather than in the middle of the day.

Aftermath

Cebu Provincial Governor Lito Osmena"It looked like it was a Nazi death camp. Children and old people were piled on top of each other."

Initially, it took more than 24 hours for word of the level of devastation to reach officials in Manila as communications across Leyte were largely destroyed. By November 7, search and rescue operations were underway across Leyte and Negros Occidental. The first shipment of relief supplies, consisting of food rations, rice, sardines, and used clothing, was to be shipped from Cebu later that day. On November 8, Philippine President Corazon Aquino declared all of Leyte a disaster area. A Philippine Navy vessel set out with heavy earth-moving machinery and the Philippine Air Force deployed aircraft to assist in rescue efforts. Relief efforts in Ormoc City were hampered by a lack of clear roads and fuel. Amateur radio reports stated that an AC-130 was able to land at a local airport but materials had to be moved by helicopter from there since roads were blocked. Relief efforts were also hampered by continuing rains and the rough terrain of the affected region. By November 11, approximately 8,300 families had been rescued and another 7,521 were evacuated from affected regions.

Supply distribution centers were established in Ormoc, providing residents with food, water, and materials, by November 11. People were given a can of sardines and 1 kg (2.2 lb) of rice at these centers. These centers were only able to operate in daylight though due to a lack of fuel and transportation. Water was supplied in limited quantities from Cebu. Medical and sanitation teams were deployed throughout the province, with many coming from surrounding areas. Residents searched through debris for lumber to construct makeshift coffins while others stacked bodies to be picked up by wheelbarrows or trucks. Officials had difficulty determining how to best deal with mass casualties as bodies lay across the Ormoc region. Many were found in the coastal barangays of Linao, Camp Downes, and Bantigue as well as the Ormoc pier. In order to prevent the spread of disease, mass graves were dug, with 700 bodies buried on November 8. Dump trucks were used to transport the dead to these sites as quickly as possible. As decomposition set in, residents stated that " putrid smell was unbearable." Even months after the storm, bodies were occasionally discovered, some found in drainage systems. By November 10, four navy vessels were searching debris in the waters near Ormoc for bodies; 16 were recovered that day with more believed to be submerged in the bay. Roads surrounding the city were finally cleared by November 12; however, electricity remained out. With the deployment of medical teams from Japan, hospitals in the region returned to full capacity. By November 22, electricity and water had been 70 percent and 60 percent restored, respectively. The emergency phase of assistance ended on November 29 and coordination of disaster relief was returned to the Philippines. By that time, national aid to Ormoc reached $1.1 million, with more than half coming from a presidential grant.

| Rank | Storm | Season | Fatalities | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Yolanda (Haiyan) | 2013 | 6,300 | |

| 2 | Uring (Thelma) | 1991 | 5,101–8,000 | |

| 3 | Pablo (Bopha) | 2012 | 1,901 | |

| 4 | "Angela" | 1867 | 1,800 | |

| 5 | Winnie | 2004 | 1,593 | |

| 6 | "October 1897" | 1897 | 1,500 | |

| 7 | Nitang (Ike) | 1984 | 1,426 | |

| 8 | Reming (Durian) | 2006 | 1,399 | |

| 9 | Frank (Fengshen) | 2008 | 1,371 | |

| 10 | Sendong (Washi) | 2011 | 1,257 |

On November 7, despite no official appeal for international aid, the governments of France and the United States provided $34,783 and $25,000 in funds. The request for assistance came the following day, with the Philippines requesting food, water, medicine, emergency supplies, and heavy machinery. A team from the United Nations Disaster Relief Organization, specializing with relief coordination and flood management, was also sent. The Red Cross appealed for $418,000 to support 15,000 families for one month. A cash grant of $17,300 from the United Kingdom was received on November 8. Two United States Air Force AC-130s from Subic bay naval base flew to Cebu carrying ready-to-eat meals. International funding reached $2.5 million on November 12, with grants of $1.05 million, $1 million, $188,000 from the Netherlands, Japan, and Australia respectively. Additionally, the United States provided 55,000 packages of food rations. This total nearly doubled two days later with grants from the United Nations Development Programme, World Food Programme, World Vision International, Médecins Sans Frontières, Caritas, various branches of the Red Cross, and the governments of Canada and New Zealand. Ultimately, approximately $5.8 million was provided in international assistance from 13 nations, the United Nations, the Red Cross, and various non-governmental organizations.

Isle Verde, where approximately 2,300 people were killed, was declared uninhabitable by officials; however, residents still returned to the area due to a need for land. Eventually, signs that used to warn people not to stay on the islet were eventually taken down and people were no longer warned not to live there. A resettlement community was constructed months later, with plans to house 912 of the 2,668 families that needed to be moved from the area. Those that were not moved were left on Isle Verde despite orders not to stay there. Another resettlement project for 700 families was planned at the cost of $1 million.

The sheer magnitude of the flood event in the Anilao–Malbasag watershed made the region more vulnerable to future flood events. Hillsides became more unstable and the rivers themselves were clogged with debris, raising their water levels and widening their banks. In a post-disaster assessment in October 1992, it was stated that swift cooperation of all agencies from local to governmental was necessary to prevent tragedies of similar caliber in the future. It was urged that residents still living along the river banks be relocated to safer areas; however, by the time of the report, people had already begun repopulating the area. As a way of avoiding similar breaching of the riverbank, it was suggested that the two rivers be dredged and possibly re-channeled. Several points were also brought up about rehabilitating the landscape of the watershed: reforestation, contoured farming, and redesigning of plantations to better retain rainwater. Long-term rehabilitation of the watershed was deemed necessary in addition to repairing infrastructure in Ormoc.

In 1993, following a request by the Philippine Government, the Japan International Cooperation Agency conducted as study on flood control for Ormoc and other cities across the country. In 1998, an ₱800 million (US$20.6 million) construction project for flood mitigation was approved and later completed in 2001. That year, Tropical Depression Auring caused flooding of similar magnitude to Thelma; however, the waters were properly diverted to the sea. A sculpture and monument to the victims, designed by architect Maribeth Ebcas and artist Florence Cinco respectively, called "Gift of Life" was constructed on a 1.3 km (0.50 sq mi) plot of land. It was designed to also depict a need to respect nature and be a message of hope for residents in Ormoc.

Due to the catastrophic loss of life caused by the storm, the name Thelma was retired and replaced with Teresa.

See also

- List of retired Pacific typhoon names (JMA)

- Typhoons in the Philippines

- 2006 Southern Leyte mudslide

- Other Philippine tropical cyclones that have claimed more than 1,000 lives

- Other disasters that took place in the Philippines around the time of Thelma

Notes

- All damage totals are in 1991 values.

- The death and missing columns includes deaths caused by Typhoon Fengshen (Frank), in the MV Princess of the Stars disaster.

References

- General

- Dennis J. Parker (2000). Floods. Vol. 1. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-22743-8.

- Specific

- Pedro Ribera, Ricardo Garcia-Herrera and Luis Gimeno (July 2008). "Historical deadly typhoons in the Philippines" (PDF). Weather. 63 (7): 196. Bibcode:2008Wthr...63..194R. doi:10.1002/wea.275. S2CID 122913766.

- Dominic Alojado and Michael Padua (July 29, 2010). "The Twelve Worst Typhoons Of The Philippines (1947–2009)". Typhoon2000. Archived from the original on September 19, 2019. Retrieved May 6, 2013.

- "Updates re Effects of Typhoo "Yolanda" (Haiyan)" (PDF). National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Council. April 17, 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 6, 2014. Retrieved April 17, 2014.

- ^ "Annual Tropical Cyclone Report: Typhoon Thelma (27W)" (PDF). Joint Typhoon Warning Center. United States Navy. 1992. pp. 132–135. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 13, 2020. Retrieved May 3, 2013.

- ^ "1991 Thelma (1991304N08140)". International Best Track Archive. 2013. Retrieved May 3, 2013.

- "Destructive Typhoons 1970-2003". National Disaster Coordinating Council. November 9, 2004. Archived from the original on November 12, 2004. Retrieved May 3, 2013.

- ^ Environmental Research Division, Manila Observatory (October 1992). "The Ormoc City Tragedy of November 5, 1991: Chapter 2: Meteorological Conditions" (PDF). Environmental Science for Social Change: 10–16. Retrieved May 3, 2013.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Report on Cyclonic Disturbances (Depressions and Tropical Cyclones) over North Indian Ocean in 1991 (PDF) (Report). India Meteorological Department. January 1992. pp. 5–6. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved March 27, 2016.

- Bob Droggin (Los Angeles Times) (November 7, 1991). "Storm-triggered mudslides, floods kill 2,300 Filipinos". The News-Journal. Manila, Philippines. p. A1. Retrieved May 6, 2013.

- Dominic Alojado and Michael Padua (July 29, 2010). "20 Worst Typhoons of the Philippines (1947–2009)". Typhoon2000. Archived from the original on April 18, 2021. Retrieved May 6, 2013.

- ^ Environmental Research Division, Manila Observatory (October 1992). "The Ormoc City Tragedy of November 5, 1991 Chapter 1: The Ormoc City Tragedy" (PDF). Environmental Science for Social Change: 3–9. Retrieved May 3, 2013.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Floods, landslides from tropical storm kill 2,337 in Philippines". The Pittsburgh Press. Tacloban, Philippines. Associated Press. November 6, 1991. p. A1. Retrieved May 3, 2013.

- ^ "Philippines Floods Nov 1991 UNDRO Situation Reports 1-8". United Nations Department of Humanitarian Affairs. ReliefWeb. November 29, 1991. Retrieved May 3, 2013.

- Parker, p. 400

- ^ Environmental Research Division, Manila Observatory (October 1992). "The Ormoc City Tragedy of November 5, 1991: Chapter 4: Contributing Physical Factors" (PDF). Environmental Science for Social Change: 19–29. Retrieved May 3, 2013.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Environmental Research Division, Manila Observatory (October 1992). "The Ormoc City Tragedy of November 5, 1991 Chapter 3: Flood Event" (PDF). Environmental Science for Social Change: 17–18. Retrieved May 3, 2013.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Environmental Research Division, Manila Observatory (October 1992). "The Ormoc City Tragedy of November 5, 1991: Chapter 6: Critical Social Conditions" (PDF). Environmental Science for Social Change: 30–32. Retrieved May 3, 2013.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Environmental Research Division, Manila Observatory (October 1992). "The Ormoc City Tragedy of November 5, 1991: Chapter 6: Evaluation" (PDF). Environmental Science for Social Change: 33–40. Retrieved May 3, 2013.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Bob Drogin (November 7, 1991). "2,300 Dead as Storm Batters the Philippines". Los Angeles Times. Manila, Philippines. Retrieved May 3, 2013.

- ^ Marites Dañguilan-Vitug. "The Politics of Disaster" (PDF). Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 10, 2014. Retrieved May 3, 2013.

- ^ Monte L. Peterson (July 1992). "Reconnaissance Report: Flooding Resulting From Typhoon Uring In Ormoc City, Leyte Province, The Philippines" (PDF). United States Army Corps of Engineers. pp. 1–49. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 15, 2014. Retrieved May 3, 2013.

- ^ Cris Evert Lato (November 12, 2010). "Ormoc rises from flash flood tragedy". The Inquirer. Ormoc, Philippines.

- "Tropical Storm Thelma: Survivors looks for relatives in aftermath". The Vindicator. Ormoc, Philippines. Associated Press. November 7, 1991. p. A6. Retrieved May 6, 2013.

- ^ "The Philippines: Search continues for bodies of victims". The Vindicator. Manila, Philippines. Associated Press. November 9, 1991. p. A3. Retrieved May 7, 2013.

- ^ "Mass burials mark Thelma's destruction". The Vindicator. Ormoc, Philippines. Associated Press. November 8, 1991. p. A8. Retrieved May 7, 2013.

- "2nd storm heads to ravaged Philippines". The Times-News. Manila, Philippines. Associated Press. November 10, 1991. p. 9A. Retrieved May 7, 2013.

- Del Rosario, Eduardo D (August 9, 2011). Final Report on Typhoon "Yolanda" (Haiyan) (PDF) (Report). Philippine National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Council. pp. 77–148. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 5, 2020. Retrieved March 27, 2022.

- ^ Alojado, Dominic (2015). Worst typhoons of the Philippines (1947-2014) (PDF) (Report). Weather Philippines. Retrieved September 25, 2015.

- ^ "10 Worst Typhoons that Went Down in Philippine History". M2Comms. August 3, 2016. Retrieved August 3, 2016.

- Lotilla, Raphael (November 20, 2013). "Flashback: 1897, Leyte and a strong typhoon". Rappler. Retrieved July 10, 2014.

- "Deadliest typhoons in the Philippines". ABS-CBNNews. November 8, 2013. Archived from the original on November 13, 2013. Retrieved November 8, 2013.

- Padua, David M (June 10, 2011). "Tropical Cyclone Logs: Fengshen (Frank)". Typhoon 2000. Archived from the original on December 1, 2010. Retrieved December 31, 2011.

- Rabonza, Glenn J. (July 31, 2008). Situation Report No. 33 on the Effects of Typhoon "Frank"(Fengshen) (PDF) (Report). National Disaster Coordinating Council (National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Center). Archived (PDF) from the original on September 27, 2013. Retrieved December 31, 2011.

- 2011 Top 10 Philippine Destructive Tropical Cyclones. Government of the Philippines (Report). January 6, 2012. ReliefWeb. Retrieved July 24, 2023.

- Environmental Research Division, Manila Observatory (October 1992). "The Ormoc City Tragedy of November 5, 1991: Chapter 7: Recommendations" (PDF). Environmental Science for Social Change: 41–43. Retrieved May 3, 2013.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Xiaotu Lei and Xiao Zhou (Shanghai Typhoon Institute of China Meteorological Administration) (February 2012). "Summary of Retired Typhoons in the Western North Pacific Ocean". Tropical Cyclone Research and Review. 1 (1): 23–32. Bibcode:2012TCRR....1...23L. doi:10.6057/2012TCRR01.03. Retrieved May 3, 2013.

External links

- Japan Meteorological Agency

- Joint Typhoon Warning Center Archived 2010-03-01 at the Wayback Machine

| Tropical cyclones of the 1991 Pacific typhoon season | ||

|---|---|---|

| STSSharon TYTim TSVanessa VSTYWalt TDTD TYYunya TDTD TDTD TYZeke VSTYAmy TDTD STSBrendan TYCaitlin TDEnrique TDTD TDDoug TYEllie TYFred TD13W STSGladys TDTD TD15W TSHarry VSTYIvy TSJoel TYKinna VSTYMireille STSLuke TYNat VSTYOrchid VSTYPat VITYRuth VSTYSeth TSThelma STSVerne TSWilda VITYYuri STSZelda | |

| Retired Pacific typhoon names | |

|---|---|

| Pre-2000s | |

| 2000s | |

| 2010s |

|

| 2020s | |

| Typhoon names retired by PAGASA | |

|---|---|

| 1960s | |

| 1970s | |

| 1980s | |

| 1990s | |

| 2000s | |

| 2010s | |

| 2020s | |