| Pacanne | |

|---|---|

| P'Koum-Kwa | |

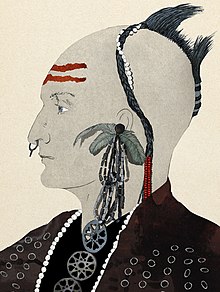

Chief Pacan. Image provided by Valencian Museum of Ethnology Chief Pacan. Image provided by Valencian Museum of Ethnology | |

| Miami leader | |

| Succeeded by | Jean Baptiste Richardville |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 1737 (1737) |

| Died | 1816 (aged 78–79) |

| Relations | Tacumwah |

Pacanne (c. 1737–1816) was a leading Miami chief during the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Son of The Turtle (Aquenackqua), he was the brother of Tacumwah, who was the mother of Chief Jean Baptiste Richardville. Their family owned and controlled the Long Portage, an 8-mile strip of land between the Maumee and Wabash Rivers used by traders travelling between Canada and Louisiana. As such, they were one of the most influential families of Kekionga.

Pacanne (P'Koum-Kwa) was probably the nephew of Cold Foot, the Miami Chief of Kekionga until a smallpox epidemic took his life in 1752. One of the earliest references to Pacanne comes from Captain Thomas Morris, who had been sent by the British to secure Kekionga, Ouiatenon, Vincennes, and Kaskaskia following Pontiac's Rebellion. In 1764, at Fort Miamis, near Kekionga, two Miami warriors dragged him to the village and tied him to a pole with the intent of executing him. According to his report, Pacanne, still a minor, rode up and released him. This may have been a staged event, signalling Pacanne's assumption of leadership.

As a chief and businessman, Pacanne travelled extensively, visiting villages as distant as Vincennes, Fort Detroit, Quebec City, and Fort Niagara. While gone, Kekionga was managed by Tacumwah and her son, as well as by nearby chiefs Little Turtle and Le Gris. Pacanne's frequent absence led to some misunderstandings that Le Gris was his superior.

In Autumn of 1778, during the American Revolution, Pacanne accompanied British Lt-Governor Henry Hamilton down the Wabash River to recapture Vincennes. There, he told Piankeshaw chiefs Young Tobacco and Old Tobacco—who had supported the rebelling Americans—to pay attention to Hamilton.

Following a November 1780 raid on Kekionga by a French colonial militia under Augustin de La Balme, he openly declared support for the British. Referring to the colonial French, Pacanne said, "You see our village stained with blood, you can think that we are not going to extend the hand to your friends who are our enemies. You can understand that if we find you with them that we will not make any distinction." Following up on this threat, the Miami of Kekionga requested aid in attacking Vincennes; the attack never occurred because the British aid never came. British commander Arent DePeyster singled out Pacanne's loyalty, saying they shared the same mind regarding the war.

After the American Revolution, Pacanne worked as an emissary between the new United States and the Miami Confederacy. He was a guide for Colonel Josiah Harmar and worked with Major Jean François Hamtramck. In August 1788, however, a band of Kentucky men led by Patrick Brown attacked a Piankeshaw village near Vincennes and escaped. Although Major Hamtramck promised to punish the invaders, he was powerless to actually do so. When Pacanne returned to Vincennes and learned of the attack, he broke off communications with Hamtramck and returned to Kekionga.

The next several years saw many major battles between the United States Army and the native nations in what has become known as the Northwest Indian War. Kekionga was the base of many raids against American settlers. Consequently, it was the target of American expeditions, leading to Hardin's Defeat, Harmar's Defeat, and St. Clair's Defeat. These conflicts ended with the Battle of Fallen Timbers and the Treaty of Greenville in 1795. Miami war chief Little Turtle attended and signed the treaty on behalf of the Miami, but Pacanne did not attend, instead sending his nephew, Chief Richardville. When approached later, Pacane still refused to sign. Even so, the chiefs encouraged compliance with the treaty, and opposed younger leaders—specifically Tecumseh—who continued to lead resistance against the Americans. Pacanne moved to a village near the mouth of the Mississinewa River, near present-day Peru, Indiana. He actively sought better relations with the new United States, and remained neutral at the onset of the War of 1812. But after American retaliation for the Fort Dearborn Massacre, Pacanne again allied with the British.

Pacanne died in 1816 and was succeeded by his nephew, Jean Baptiste Richardville.

References

- Carter, images between Part One pg 62 and Part Two pg 65. Another sketch was made in 1794 by the wife of Lt-Gov John Graves Simcoe, and it is very similar.

- "Ancestry". ancestry.com. Retrieved 22 November 2010.

- Carter, 65-67

- Journal of Captain Thomas Morris (Detroit, 25 September 1764)

- Carter, pg 68

- Carter, 128

- Carter, 77

- Anson, 104

- Hamilton refers to 'Pacane' periodically in his journal. On the 24 November 1778 entry, Hamilton says Pacane means 'The Nut' (Pecan). The Vincennes meeting with all the chiefs occurred on 20 December 1778.

- Birzer

- Anson, pgs 106-107

- Carter, 146

- Anson, pg 136

- Anson, pg 139

- Wheeler-Voegelin, pgs 68 Archived 2008-03-15 at the Wayback Machine - 69 Archived 2008-03-15 at the Wayback Machine.

- Libby, pg 140 Archived 2008-03-15 at the Wayback Machine

- Barr, pg 145

Sources

- Anson, Bert. The Miami Indians. ©2000. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-3197-7.

- Barr, Daniel P., editor The Boundaries between Us: Natives and Newcomers along the Frontiers of the Old Northwest Territory, 1750–1850. ©2006, Kent State University Press. ISBN 0-87338-844-5.

- Birzer, Bradley J. French Imperial remnants on the middle ground: The strange case of August de la Balme and Charles Beaubien. Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society, Summer 2000.

- Carter, Harvey Lewis. The Life and Times of Little Turtle: First Sagamore of the Wabash. ©1987, Urbana: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0-252-01318-2.

- "Henry Hamilton's Journal, 1778–1779", from the Indiana Historical Bureau

- Libby, Dr. Dorothy. An Anthropological Report on the Piankashaw Indians, Dockett 99 (a part of Consolidated Docket No. 315) ©1996, Glenn Black Laboratory of Archaeology and The Trustees of Indiana University.

- Morris, Captain Thomas (of His Majesty's XVII Regiment of Infantry) in: Thwaites, Early Western Travels, vol. I, pp. 301-328. Available online at the Glenn A. Black Laboratory of Archaeology website.

- Wheeler-Voegelin Dr. Erminie; Blasingham, Dr. Emily J.; and Libby, Dr. Dorothy R. An Anthropological Report on the History of the Miamis, Weas, and Eel River Indians, Vol 1. ©1997. Available online at the Glenn A. Black Laboratory of Archaeology website.