| Fertility awareness | |

|---|---|

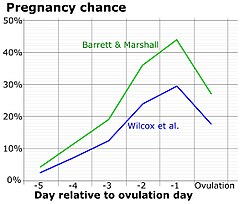

Chance of fertilization by day relative to ovulation. Chance of fertilization by day relative to ovulation. | |

| Background | |

| Type | Behavioral |

| First use | 1950s (mucus) mid-1930s (BBT) 1930 (Knaus-Ogino) Ancient (ad hoc) |

| Failure rates (first year) | |

| Perfect use | Symptothermal method: 0.4% Ovulation method: 3% TwoDay method: 4% Standard Days method: 5% |

| Typical use | Symptothermal method: 2% Ovulation Method: 11–34% TwoDay Method: 14% Standard Days Method: 11–14% Calendar Rhythm Method: 24% |

| Usage | |

| Reversibility | Yes |

| User reminders | Dependent upon strict user adherence to methodology |

| Clinic review | None |

| Advantages and disadvantages | |

| STI protection | No |

| Periods | Increased prediction |

| Benefits | No side effects, can aid pregnancy achievement, personal self-awareness, greater marital intimacy |

Fertility awareness (FA) refers to a set of practices used to determine the fertile and infertile phases of a woman's menstrual cycle. Fertility awareness methods may be used to avoid pregnancy, to achieve pregnancy, or as a way to monitor gynecological health.

Methods of identifying infertile days have been known since antiquity, but scientific knowledge gained during the past century has increased the number, variety, and especially accuracy of methods.

Systems of fertility awareness rely on observation of changes in one or more of the primary fertility signs (basal body temperature, cervical mucus, and cervical position), tracking menstrual cycle length and identifying the fertile window based on this information, or both. Other signs may also be observed: these include breast tenderness and mittelschmerz (ovulation pains), urine analysis strips known as ovulation predictor kits (OPKs), and microscopic examination of saliva or cervical fluid. Also available are computerized fertility monitors.

Terminology

Symptoms-based methods involve tracking one or more of the three primary fertility signs: basal body temperature, cervical mucus, and cervical position. Systems relying exclusively on cervical mucus include the Billings Ovulation Method, the Creighton Model, and the Two-Day Method. Symptothermal methods combine observations of basal body temperature (BBT), cervical mucus, and sometimes cervical position. Calendar-based methods rely on tracking a woman's cycle and identifying her fertile window based on the lengths of her cycles. The best known of these methods is the Standard Days Method. The Calendar-Rhythm method is also considered a calendar-based method, though it is not well defined and has many different meanings to different people.

Systems of fertility awareness may be referred to as fertility awareness–based methods; the term Fertility Awareness Method (FAM) refers specifically to the system taught by Toni Weschler. The term natural family planning is sometimes used to refer to any use of fertility awareness methods, the lactational amenorrhea method and periodic abstinence during fertile times. A method of fertility awareness may be used by natural family planning users to identify these fertile times.

Women who are breastfeeding a child and wish to avoid pregnancy may be able to practice the lactational amenorrhea method. The lactational amenorrhea method is distinct from fertility awareness, but because it also does not involve contraceptives, it is often presented alongside fertility awareness as a method of "natural" birth control.

Within the Catholic Church and some Protestant denominations, the term natural family planning is often used to refer to Fertility Awareness pointing out it is the only method of family planning approved by the Church.

History

Development of calendar-based methods

Main article: Calendar-based methods § HistoryIt is not known exactly when it was first discovered that women have predictable periods of fertility and infertility. It is already clearly stated in the Talmud tractate Niddah, that a woman only becomes pregnant in specific periods in the month, which seemingly refers to ovulation. St. Augustine wrote about periodic abstinence to avoid pregnancy in the year 388 (the Manichaeans attempted to use this method to remain childfree, and Augustine condemned their use of periodic abstinence). One book states that periodic abstinence was recommended "by a few secular thinkers since the mid-nineteenth century," but the dominant force in the twentieth century popularization of fertility awareness-based methods was the Roman Catholic Church.

In 1905 Theodoor Hendrik van de Velde, a Dutch gynecologist showed that women only ovulate once per menstrual cycle. In the 1920s, Kyusaku Ogino, a Japanese gynecologist, and Hermann Knaus, from Austria, independently discovered that ovulation occurs about fourteen days before the next menstrual period. Ogino used his discovery to develop a formula for use in aiding infertile women to time intercourse to achieve pregnancy. In 1930, John Smulders, a Roman Catholic physician from the Netherlands, used this discovery to create a method for avoiding pregnancy. Smulders published his work with the Dutch Roman Catholic medical association, and this was the first formalized system for periodic abstinence: the rhythm method.

Introduction of temperature and cervical mucus signs

In the 1930s, Reverend Wilhelm Hillebrand, a Catholic priest in Germany, developed a system for avoiding pregnancy based on basal body temperature. This temperature method was found to be more effective at helping women avoid pregnancy than were calendar-based methods. Over the next few decades, both systems became widely used among Catholic women. Two speeches delivered by Pope Pius XII in 1951 gave the highest form of recognition to the Catholic Church's approval—for couples who needed to avoid pregnancy—of these systems. In the early 1950s, John Billings discovered the relationship between cervical mucus and fertility while working for the Melbourne Catholic Family Welfare Bureau. Billings and several other physicians, including his wife, Dr. Evelyn Billings, studied this sign for a number of years, and by the late 1960s had performed clinical trials and begun to set up teaching centers around the world.

First symptoms-based teaching organizations

While Dr. Billings initially taught both the temperature and mucus signs, they encountered problems in teaching the temperature sign to largely illiterate populations in developing countries. In the 1970s they modified the method to rely on only mucus. The international organization founded by Dr. Billings is now known as the World Organization Ovulation Method Billings.

The first organization to teach a symptothermal method was founded in 1971. John and Sheila Kippley, lay Catholics, joined with Dr. Konald Prem in teaching an observational method that relied on all three signs: temperature, mucus, and cervical position. Their organization is now called Couple to Couple League International. The next decade saw the founding of other now-large Catholic organizations, Family of the Americas (1977), teaching the Billings method, and the Pope Paul VI Institute (1985), teaching a new mucus-only system called the Creighton Model.

Up until the 1980s, information about fertility awareness was only available from Catholic sources. The first secular teaching organization was the Fertility Awareness Center in New York, founded in 1981. Toni Weschler started teaching in 1982 and published the bestselling book Taking Charge of Your Fertility in 1995. Justisse was founded in 1987 in Edmonton, Canada. These secular organizations all teach symptothermal methods. Although the Catholic organizations are significantly larger than the secular fertility awareness movement, independent secular teachers have become increasingly common since the 1990s.

Ongoing development

Development of fertility awareness methods is ongoing. In the late 1990s, the Institute for Reproductive Health at Georgetown University introduced two new methods. The TwoDay Method, a mucus-only system, and CycleBeads and iCycleBeads (the digital version), based on the Standard Days Method, are designed to be both effective and simple to teach, learn, and use. In 2019, Urrutia et al. released a study as well as interactive graph over-viewing all studied fertility awareness based methods. Femtech companies such as Dot and Natural Cycles have also produced new studies and apps to help women avoid pregnancy. Natural Cycles is the first app of its kind to receive FDA approval.

Fertility signs

Most menstrual cycles have several days at the beginning that are infertile (pre-ovulatory infertility), a period of fertility, and then several days just before the next menstruation that are infertile (post-ovulatory infertility). The first day of red bleeding is considered day one of the menstrual cycle. Different systems of fertility awareness calculate the fertile period in slightly different ways, using primary fertility signs, cycle history, or both.

Primary fertility signs

The three primary signs of fertility are basal body temperature (BBT), cervical mucus, and cervical position. A woman practicing symptoms-based fertility awareness may choose to observe one sign, two signs, or all three. Many women experience secondary fertility signs that correlate with certain phases of the menstrual cycle, such as abdominal pain and heaviness, back pain, breast tenderness, and mittelschmerz (ovulation pains).

Basal body temperature

This usually refers to a temperature reading collected when a person first wakes up in the morning (or after their longest sleep period of the day). The true BBT can only be obtained by continuous temperature monitoring through internally worn temperature sensors. In women, ovulation will trigger a rise in BBT between 0.2º and 0.5 °C. (0.5 and 1.°F) that lasts approximately until the next menstruation. This temperature shift may be used to determine the onset of post-ovulatory infertility. (See ref. 30)

Cervical mucus

The appearance of cervical mucus and vulvar sensation are generally described together as two ways of observing the same sign. Cervical mucus is produced by the cervix, which connects the uterus to the vaginal canal. Fertile cervical mucus promotes sperm life by decreasing the acidity of the vagina, and also it helps guide sperm through the cervix and into the uterus. The production of fertile cervical mucus is caused by estrogen, the same hormone that prepares a woman's body for ovulation. By observing her cervical mucus and paying attention to the sensation as it passes the vulva, a woman can detect when her body is gearing up for ovulation, and also when ovulation has passed. When ovulation occurs, estrogen production drops slightly and progesterone starts to rise. The rise in progesterone causes a distinct change in the quantity and quality of mucus observed at the vulva.

Cervical position

The cervix changes position in response to the same hormones that cause cervical mucus to be produced and to dry up. When a woman is in an infertile phase of her cycle, the cervix will be low in the vaginal canal; it will feel firm to the touch (like the tip of a person's nose); and the os—the opening in the cervix—will be relatively small, or "closed". As a woman becomes more fertile, the cervix will rise higher in the vaginal canal, it will become softer to the touch (more like a person's lips), and the os will become more open. After ovulation has occurred, the cervix will revert to its infertile position.

Cycle history

Calendar-based systems determine both pre-ovulatory and post-ovulatory infertility based on cycle history. When used to avoid pregnancy, these systems have higher perfect-use failure rates than symptoms-based systems but are still comparable with barrier methods, such as diaphragms and cervical caps.

Mucus- and temperature-based methods used to determine post-ovulatory infertility, when used to avoid conception, result in very low perfect-use pregnancy rates. However, mucus and temperature systems have certain limitations in determining pre-ovulatory infertility. A temperature record alone provides no guide to fertility or infertility before ovulation occurs. Determination of pre-ovulatory infertility may be done by observing the absence of fertile cervical mucus; however, this results in a higher failure rate than that seen in the period of post-ovulatory infertility. Relying only on mucus observation also means that unprotected sexual intercourse is not allowed during menstruation, since any mucus would be obscured.

The use of certain calendar rules to determine the length of the pre-ovulatory infertile phase allows unprotected intercourse during the first few days of the menstrual cycle while maintaining a very low risk of pregnancy. With mucus-only methods, there is a possibility of incorrectly identifying mid-cycle or anovulatory bleeding as menstruation. Keeping a basal body temperature chart enables accurate identification of menstruation, when pre-ovulatory calendar rules may be reliably applied. In temperature-only systems, a calendar rule may be relied on alone to determine pre-ovulatory infertility. In symptothermal systems, the calendar rule is cross-checked by mucus records: observation of fertile cervical mucus overrides any calendar-determined infertility.

Calendar rules may set a standard number of days, specifying that (depending on a woman's past cycle lengths) the first three to six days of each menstrual cycle are considered infertile. Or, a calendar rule may require calculation, for example holding that the length of the pre-ovulatory infertile phase is equal to the length of a woman's shortest cycle minus 21 days. Rather than being tied to cycle length, a calendar rule may be determined from the cycle day on which a woman observes a thermal shift. One system has the length of the pre-ovulatory infertile phase equal to a woman's earliest historical day of temperature rise minus seven days.

Other techniques

Ovulation predictor kits can detect imminent ovulation from the concentration of luteinizing hormone (LH) in a woman's urine. A positive ovulation predictor kit result is usually followed by ovulation within 12–36 hours.

Saliva microscopes, when correctly used, can detect ferning structures in the saliva that precede ovulation. Ferning is usually detected beginning three days before ovulation, and continuing until ovulation has occurred. During this window, ferning structures occur in cervical mucus as well as saliva.

Computerized fertility monitors, such as Lady-Comp, are available under various brand names. These monitors may use BBT-only systems, they may analyze urine test strips, they may use symptothermal observations, they may monitor the electrical resistance of saliva and vaginal fluids, or a combination of any of these factors.

A symptohormonal method of fertility awareness method developed at Marquette University uses the ClearBlue Easy fertility monitor to determine the fertile window. The monitor measures estrogen and LH to determine the peak day. This method is also applicable during postpartum, breastfeeding, and perimenopause, and requires less abstinence than other fertility awareness method methods. Some couples prefer this method because the monitor reading is objective and is not affected by sleep quality as basal body temperature can be.

Benefits and drawbacks

Fertility awareness has a number of unique characteristics:

- Fertility awareness can be used to monitor reproductive health. Changes in the cycle can alert the user to emerging gynecological problems. Fertility awareness can also be used to aid in diagnosing known gynecological problems such as infertility.

- Fertility awareness may be used to avoid pregnancy or to aid in conception.

- Use of fertility awareness can give insight to the workings of women's bodies, and may allow women to take greater control of their own fertility.

- Some symptoms-based forms of fertility awareness require observation or touching of cervical mucus, an activity with which some women are not comfortable. Some practitioners prefer to use the term "cervical fluid" to refer to cervical mucus, in an attempt to make the subject more acceptable to these women.

- Some drugs, such as decongestants, can change cervical mucus. In women taking these drugs, the mucus sign may not accurately indicate fertility.

- Some symptoms-based methods require tracking of basal body temperatures. Because irregular sleep can interfere with the accuracy of basal body temperatures, shift workers and those with very young children, for example, might not be able to use those methods.

- FA requires action daily—detailed record keeping. Some may find the time and detail requirements too complicated.

As birth control

By restricting unprotected sexual intercourse to the infertile portion of the menstrual cycle, a woman and her partner can prevent pregnancy. During the fertile portion of the menstrual cycle, the couple may use barrier contraception or abstain from sexual intercourse.

Advantages

- There are no drug-related side effects to fertility awareness.

- FA can be free or have a very low up-front cost. Users may employ a coach, use computer software, or buy a chart, calendar, or basal thermometer. The direct costs are low when compared to other methods.

- FA can be used with barrier contraception so that intercourse may continue through the fertile period. Unlike barrier use without FA, practicing FA can allow couples to use barrier contraception only when necessary.

- FA can be used to immediately switch from pregnancy avoidance to pregnancy planning if the couple decides it is time to plan for conception.

Disadvantages

- Use of a barrier or other backup method is required on fertile days; otherwise the couple must abstain. To reduce pregnancy risk to below 1% per year, there are an average of 13 days where abstinence or backup must be used during each cycle. For women with very irregular cycles—such as those common during breastfeeding, perimenopause, or with hormonal diseases such as PCOS—abstinence or the use of barriers may be required for months at a time.

- Typical use effectiveness is lower than most other methods.

- Fertility awareness does not protect against sexually transmitted disease.

Effectiveness

The effectiveness of fertility awareness, as of most forms of contraception, can be assessed two ways. Perfect use or method effectiveness rates only include people who follow all observational rules, correctly identify the fertile phase, and refrain from unprotected intercourse on days identified as fertile. Actual use or typical use effectiveness rates include all women relying on fertility awareness to avoid pregnancy, including those who fail to meet the "perfect use" criteria. Rates are generally presented for the first year of use. Most commonly, the Pearl Index is used to calculate effectiveness rates, but some studies use decrement tables.

The failure rate of fertility awareness varies widely depending on the system used to identify fertile days, the instructional method, and the population being studied. Some studies have found actual failure rates of 25% per year or higher. At least one study has found a failure rate of less than 1% per year with continuous intensive coaching and monthly review, and several studies have found actual failure rates of 2%–3% per year.

When used correctly and consistently (i.e., with perfect use) with ongoing coaching, under study conditions some studies have found some forms of FA to be 99% effective.

From Contraceptive Technology:

- Post-ovulation methods (i.e., abstaining from intercourse from menstruation until after ovulation) have a method failure rate of 1% per year.

- The symptothermal method has a method failure rate of 2% per year.

- Cervical mucus–only methods have a method failure rate of 3% per year.

- Calendar rhythm has a method failure rate of 9% per year.

- The Standard Days Method has a method failure rate of 5% per year.

Reasons for lower typical-use effectiveness

Several factors account for typical-use effectiveness being lower than perfect-use effectiveness:

- conscious user non-compliance with instructions (having unprotected intercourse on a day identified as fertile)

- mistakes on the part of those providing instructions on how to use the method (instructor providing incorrect or incomplete information on the rule system)

- mistakes on the part of the user (misunderstanding of rules, mistakes in charting)

The most common reason for the lower actual effectiveness is not mistakes on the part of instructors or users, but conscious user non-compliance—that is, the couple knowing that the woman is likely to be fertile at the time but engaging in sexual intercourse nonetheless. This is similar to failures of barrier methods, which are primarily caused by non-use of the method.

To achieve pregnancy

Intercourse timing

Timing intercourse with a person's estimated 'fertile window' is a practice sometimes called 'timed intercourse'. The effectiveness of timed intercourse is not entirely clear, however, timed intercourse using urine tests that predict ovulation may help improve the rate of pregnancy and live births for some couples trying to conceive such as those who have been trying for less than 12-months and who are under 40 years old. It is not clear from medical evidence if timed intercourse improves the rate of ultra-sound confirmed pregnancies and it is also not clear if timed intercourse has an effect on a person's level of stress or their quality of life. Pregnancy rates for sexual intercourse are also affected by several other factors. Regarding frequency, there are recommendations of sexual intercourse every 1 or 2 days, or every 2 or 3 days. Studies have shown no significant difference between different sex positions and pregnancy rate, as long as it results in ejaculation into the vagina. Social science research has found that timing intercourse can become a gendered 'chore' in heterosexual married couples trying to conceive, with women tracking their ovulation cycles and dictating to their husbands when they should have sexual intercourse.

Problem diagnosis

Regular menstrual cycles are sometimes taken as evidence that a woman is ovulating normally, and irregular cycles as evidence she is not. However, many women with irregular cycles do ovulate normally, and some with regular cycles are actually anovulatory or have a luteal phase defect. Records of basal body temperatures, especially, but also of cervical mucus and position, can be used to accurately determine if a woman is ovulating, and if the length of the post-ovulatory (luteal) phase of her menstrual cycle is sufficient to sustain a pregnancy.

Fertile cervical mucus is important in creating an environment that allows sperm to pass through the cervix and into the fallopian tubes where they wait for ovulation. Fertility charts can help diagnose hostile cervical mucus, a common cause of infertility. If this condition is diagnosed, some sources suggest taking guaifenesin in the few days before ovulation to thin out the mucus.

Pregnancy testing and gestational age

Pregnancy tests are not accurate until 1–2 weeks after ovulation. Knowing an estimated date of ovulation can prevent a woman from getting false negative results due to testing too early. Also, 18 consecutive days of elevated temperatures means a woman is almost certainly pregnant. Estimated ovulation dates from fertility charts are a more accurate method of estimating gestational age than the traditional pregnancy wheel or last menstrual period (LMP) method of tracking menstrual periods. Because of high rates of very early miscarriage (25% of pregnancies are lost within the first six weeks since the woman's last menstrual period), the methods used to detect pregnancy may lead to bias in conception rates. Less-sensitive methods will detect lower conception rates, because they miss the conceptions that resulted in early pregnancy loss.

See also

- Billings ovulation method

- Creighton Model FertilityCare System

- Fertility monitor

- Lactational amenorrhea method

- Kindara

- TwoDay Method

References

- Dunson, D.B.; Baird, D.D.; Wilcox, A.J.; Weinberg, C.R. (1999). "Day-specific probabilities of clinical pregnancy based on two studies with imperfect measures of ovulation". Human Reproduction. 14 (7): 1835–1839. doi:10.1093/humrep/14.7.1835. ISSN 1460-2350. PMID 10402400.

- ^ Trussell, James (2011). "Contraceptive efficacy". In Hatcher, Robert A.; Trussell, James; Nelson, Anita L.; Cates, Willard Jr.; Kowal, Deborah; Policar, Michael S. (eds.). Contraceptive technology (20th revised ed.). New York: Ardent Media. pp. 779–863. ISBN 978-1-59708-004-0. ISSN 0091-9721. OCLC 781956734. Table 26–1 = Table 3–2 Percentage of women experiencing an unintended pregnancy during the first year of typical use and the first year of perfect use of contraception, and the percentage continuing use at the end of the first year. United States. Archived 2017-02-15 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Urrutia, Rachel Peragallo; Polis, Chelsea B. (2019-07-11). "Fertility awareness based methods for pregnancy prevention". BMJ. 366: l4245. doi:10.1136/bmj.l4245. ISSN 0959-8138. PMID 31296535. S2CID 195893695.

- Weschler, Toni (2002). Taking Charge of Your Fertility (Revised ed.). New York: HarperCollins. pp. 52. ISBN 0-06-093764-5.

- Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use:Fertility awareness-based methods. Fourth edition. World Health Organization. 2010. ISBN 978-9-2415-6388-8. Archived from the original on 2012-11-02. Retrieved 2012-12-11.

- O'Reilly, Andrea (6 April 2010). Encyclopedia of Motherhood. SAGE Publications. p. 1056. ISBN 9781452266299.

The Roman Catholic church and some Protestant denominations have approved only "natural family planning" methods--including the rhythm method and periodic abstinence.

- Green, Joel B. (1 November 2011). Dictionary of Scripture and Ethics. Baker Books. p. 303. ISBN 9781441239983.

In 1968, Paul VI reiterated the traditional Catholic prohibition against all but "natural family planning" (abstinence during fertile periods), which many Catholics and some Protestants continue to practice.

- Saint, Bishop of Hippo Augustine (1887). "Chapter 18.—Of the Symbol of the Breast, and of the Shameful Mysteries of the Manichæans". In Philip Schaff (ed.). A Select Library of the Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers of the Christian Church, Volume IV. Grand Rapids, MI: WM. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co.

- ^ Yalom, Marilyn (2001). A History of the Wife (First ed.). New York: HarperCollins. pp. 297–8, 307. ISBN 0-06-019338-7.

- "A Brief History of Fertility Charting". FertilityFriend.com. Retrieved 2006-06-18.

- ^ Singer, Katie (2004). The Garden of Fertility. New York: Avery, a member of Penguin Group (USA). pp. 226–7. ISBN 1-58333-182-4.

- ^ Hays, Charlotte. "Solving the Puzzle of Natural Family Planning". Holy Spirit Interactive. Archived from the original on 2012-02-26. Retrieved 2012-02-15.

- Moral Questions Affecting Married Life: Addresses given October 29, 1951 to the Italian Catholic Union of midwives Archived December 6, 2010, at the Wayback Machine and November 26, 1951, to the National Congress of the Family Front and the Association of Large Families, National Catholic Welfare Conference, Washington, DC.

- Billings, John (March 2002). "THE QUEST — leading to the discovery of the Billings Ovulation Method". Bulletin of Ovulation Method Research and Reference Centre of Australia. 29 (1): 18–28. Archived from the original on 2007-02-19. Retrieved 2007-03-18.

- "About us". Family of the Americas. 2006. Archived from the original on 2007-02-13. Retrieved 2007-03-18.

- "About the Institute". Pope Paul VI Institute. 2006. Archived from the original on 2012-03-12. Retrieved 2012-02-21.

- Singer (2004), p.xxiii

- "About us". Fertility Awareness Center. 2006. Retrieved 2007-03-18.

- Weschler (2002)

- Justisse Healthworks for Women. (2015). "About Us".

- Arévalo M, Jennings V, Sinai I (2002). "Efficacy of a new method of family planning: the Standard Days Method". Contraception. 65 (5): 333–8. doi:10.1016/S0010-7824(02)00288-3. PMID 12057784.

- Jennings V, Sinai I (2001). "Further analysis of the theoretical effectiveness of the TwoDay method of family planning". Contraception. 64 (3): 149–53. doi:10.1016/S0010-7824(01)00251-7. PMID 11704093.

- Jennings, Victoria H.; Haile, Liya T.; Simmons, Rebecca G.; Fultz, Hanley M.; Shattuck, Dominick (2019-01-01). "Estimating six-cycle efficacy of the Dot app for pregnancy prevention". Contraception. 99 (1): 52–55. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2018.10.002. ISSN 0010-7824. PMID 30316782.

- Health, Center for Devices and Radiological (2019-09-11). "FDA allows marketing of first direct-to-consumer app for contraceptive use to prevent pregnancy". FDA. Retrieved 2019-10-01.

- James B. Brown (2005). "Physiology of Ovulation". Ovarian Activity and Fertility and the Billings Ovulation Method. Ovulation Method Research and Reference Centre of Australia. Archived from the original on 2005-12-24.

- Kippley (2003), pp.121-134,376-381

- Kippley (2003), p.114

- Evelyn Billings; Ann Westinore (1998). The Billings Method: Controlling Fertility Without Drugs or Devices. Toronto: Life Cycle Books. p. 47. ISBN 0-919225-17-9.

- ^ Kippley (2003), pp.108-113

- Kippley (2003), p.101 sidebar and Weschler (2002), p.125

- Kippley (2003), pp.108-109 and Weschler (2002), pp.125-126

- Kippley (2003), pp.110-111

- Kippley (2003), pp.112-113

- "Institute for Natural Family Planning Model - Marquette University". www.marquette.edu. Retrieved 2022-10-11.

- Fehring, Richard J.; Schneider, Mary (2014-09-01). "Comparison of Abstinence and Coital Frequency Between 2 Natural Methods of Family Planning". Journal of Midwifery & Women's Health. 59 (5): 528–532. doi:10.1111/jmwh.12216.

- ^ "How to Observe and Record Your Fertility Signs". Fertility Friend Handbook. Tamtris Web Services. 2004. Archived from the original on 2005-05-28. Retrieved 2005-06-15.

- ^ Manhart, MD; Daune, M; Lind, A; Sinai, I; Golden-Tevald, J (January–February 2013). "Fertility awareness-based methods of family planning: A review of effectiveness for avoiding pregnancy using SORT". Osteopathic Family Physician. 5 (1): 2–8. doi:10.1016/j.osfp.2012.09.002.

- ^ Frank-Herrmann P, Heil J, Gnoth C, et al. (2007). "The effectiveness of a fertility awareness based method to avoid pregnancy in relation to a couple's sexual behaviour during the fertile time: a prospective longitudinal study". Hum. Reprod. 22 (5): 1310–9. doi:10.1093/humrep/dem003. PMID 17314078.

- James Trussell; Anjana Lalla; Quan Doan; Eileen Reyes; Lionel Pinto; Joseph Gricar (2009). "Cost effectiveness of contraceptives in the United States". Contraception. 79 (1): 5–14. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2008.08.003. PMC 3638200. PMID 19041435.

- "Fertility Awareness Method". Brown University Health Education Website. Brown University. 2012. Retrieved 2012-12-11.

- Hatcher, RA; Trussel J; Stewart F; et al. (2000). Contraceptive Technology (18th ed.). New York: Ardent Media. ISBN 0-9664902-6-6. Archived from the original on 2008-05-31. Retrieved 2008-01-01.

- Kippley, John; Sheila Kippley (1996). The Art of Natural Family Planning (4th addition ed.). Cincinnati, OH: The Couple to Couple League. p. 141. ISBN 0-926412-13-2.

- Wade ME, McCarthy P, Braunstein GD, et al. (October 1981). "A randomized prospective study of the use-effectiveness of two methods of natural family planning". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 141 (4): 368–376. doi:10.1016/0002-9378(81)90597-4. PMID 7025639.

- Medina JE, Cifuentes A, Abernathy JR, et al. (December 1980). "Comparative evaluation of two methods of natural family planning in Colombia". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 138 (8): 1142–1147. doi:10.1016/S0002-9378(16)32781-8. PMID 7446621.

- Marshall J (August 1976). "Cervical-mucus and basal body-temperature method of regulating births: field trial". Lancet. 2 (7980): 282–283. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(76)90732-7. PMID 59854. S2CID 7653268.

- ^ Evaluation of the Effectiveness of a Natural Fertility Regulation Programme in China Archived 2007-04-27 at the Wayback Machine: Shao-Zhen Qian, et al. Reproduction and Contraception (English edition), in press 2000.

- Frank-Herrmann P, Freundl G, Baur S, et al. (December 1991). "Effectiveness and acceptability of the sympto-thermal method of natural family planning in Germany". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 165 (6 Pt 2): 2052–2054. doi:10.1016/s0002-9378(11)90580-8. PMID 1755469.

- Clubb EM, Pyper CM, Knight J (1991). "A pilot study on teaching natural family planning (NFP) in general practice". Proceedings of the Conference at Georgetown University, Washington, DC. Archived from the original on 2007-03-23.

- Frank-Herrmann P, Freundl G, Gnoth C, et al. (June–September 1997). "Natural family planning with and without barrier method use in the fertile phase: efficacy in relation to sexual behavior: a German prospective long-term study". Advances in Contraception. 13 (2–3): 179–189. doi:10.1023/A:1006551921219. PMID 9288336. S2CID 24012887.

- Ecochard, R.; Pinguet, F.; Ecochard, I.; De Gouvello, R.; Guy, M.; Huy, F. (1998). "Analysis of natural family planning failures. In 7007 cycles of use". Contraception, Fertilité, Sexualité. 26 (4): 291–6. PMID 9622963.

- Hilgers, T.W.; Stanford, J.B. (1998). "Creighton Model NaProEducation Technology for avoiding pregnancy. Use effectiveness". Journal of Reproductive Medicine. 43 (6): 495–502. PMID 9653695.

- ^ Howard, M.P.; Stanford, J.B. (1999). "Pregnancy probabilities during use of the Creighton Model Fertility Care System". Archives of Family Medicine. 8 (5): 391–402. doi:10.1001/archfami.8.5.391. PMID 10500511.

- James Trussell et al. (2000) "Contraceptive effectiveness rates", Contraceptive Technology — 18th Edition, New York: Ardent Media. On-press.

- ^ Gibbons, Tatjana; Reavey, Jane; Georgiou, Ektoras X; Becker, Christian M (2023-09-15). Cochrane Gynaecology and Fertility Group (ed.). "Timed intercourse for couples trying to conceive". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2023 (9). doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011345.pub3. PMC 10501857. PMID 37709293.

- "How to get pregnant". Mayo Clinic. 2016-11-02. Retrieved 2018-02-16.

- "Fertility problems: assessment and treatment, Clinical guideline [CG156]". National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Retrieved 2018-02-16. Published date: February 2013. Last updated: September 2017

- Dr. Philip B. Imler & David Wilbanks. "The Essential Guide to Getting Pregnant" (PDF). American Pregnancy Association. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-06-01. Retrieved 2018-02-16.

- Brown E (2022). "Less Like Magic, More Like a Chore: How Sex for the Purpose of Pregnancy Becomes a Third Shift for Women in Heterosexual Couples". Sociological Forum. 37 (2): 465–85. doi:10.1111/socf.12803. S2CID 247329309.

- "Infertility fact sheet: What causes infertility in women?". womenshealth.gov. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office on Women's Health. Archived from the original on 2012-11-02. Retrieved 2012-12-11. "Some signs that a woman is not ovulating normally include irregular or absent menstrual periods."

"Female Infertility". Adult Health Advisor. 2012. Archived from the original on 2010-12-29.. "A woman who is not ovulating normally may have irregular or missed menstrual periods."

"Is Clomid Right For You?". JustMommies.com. 2007.. "If you have an irregular cycle there is a good chance you are not ovulating normally." - Weschler (2002), p. 173.

- Weschler (2002), p.316

- Weschler (2002), pp.3-4,155-156, insert p.7

Further reading

- Toni Weschler (2006). Taking Charge of Your Fertility (10th Anniversary ed.). New York: Collins. ISBN 0-06-088190-9.

- John F. Kippley; Sheila K. Kippley (1996). The Art of Natural Family Planning (Fourth ed.). Cincinnati, OH: Couple to Couple League International. ISBN 0-926412-13-2.

| Sexual and reproductive health | |

|---|---|

| Rights | |

| Education | |

| Planning | |

| Contraception | |

| Assisted reproduction |

|

| Health | |

| Pregnancy | |

| Identity | |

| Medicine | |

| Disorders | |

| By country |

|

| History | |

| Policy | |

| Menstrual cycle | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Events and phases | |||||

| Life stages | |||||

| Tracking |

| ||||

| Suppression | |||||

| Disorders | |||||

| Related events | |||||

| Mental health | |||||

| Hygiene | |||||

| In culture and religion | |||||

| Pregnancy and childbirth | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Planning | |||||||||

| Conception | |||||||||

| Testing | |||||||||

| Types | |||||||||

| Childbirth |

| ||||||||

| Prenatal |

| ||||||||

| Postpartum |

| ||||||||

| Obstetric history | |||||||||

| Birth control methods | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Related topics | |||||||

| Long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) | |||||||

| Sterilization |

| ||||||

| Hormonal contraception |

| ||||||

| Barrier Methods | |||||||

| Emergency Contraception (Post-intercourse) | |||||||

| Spermicides | |||||||

| Behavioral |

| ||||||

| Experimental | |||||||