| This article's lead section may be too short to adequately summarize the key points. Please consider expanding the lead to provide an accessible overview of all important aspects of the article. (July 2019) |

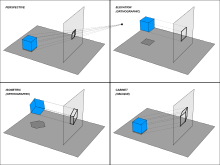

A 3D projection (or graphical projection) is a design technique used to display a three-dimensional (3D) object on a two-dimensional (2D) surface. These projections rely on visual perspective and aspect analysis to project a complex object for viewing capability on a simpler plane.

3D projections use the primary qualities of an object's basic shape to create a map of points, that are then connected to one another to create a visual element. The result is a graphic that contains conceptual properties to interpret the figure or image as not actually flat (2D), but rather, as a solid object (3D) being viewed on a 2D display.

3D objects are largely displayed on two-dimensional mediums (such as paper and computer monitors). As such, graphical projections are a commonly used design element; notably, in engineering drawing, drafting, and computer graphics. Projections can be calculated through employment of mathematical analysis and formulae, or by using various geometric and optical techniques.

Overview

Projection is achieved by the use of imaginary "projectors"; the projected, mental image becomes the technician's vision of the desired, finished picture. Methods provide a uniform imaging procedure among people trained in technical graphics (mechanical drawing, computer aided design, etc.). By following a method, the technician may produce the envisioned picture on a planar surface such as drawing paper.

There are two graphical projection categories, each with its own method:

-

Multiview projection (elevation)

Multiview projection (elevation)

-

Isometric projection

Isometric projection

-

Military projection

-

Cabinet projection

Cabinet projection

-

One-point perspective

One-point perspective

-

Two-point perspective

Two-point perspective

-

Three-point perspective

Three-point perspective

Parallel projection

Main article: Parallel projection

In parallel projection, the lines of sight from the object to the projection plane are parallel to each other. Thus, lines that are parallel in three-dimensional space remain parallel in the two-dimensional projected image. Parallel projection also corresponds to a perspective projection with an infinite focal length (the distance from a camera's lens and focal point), or "zoom".

Images drawn in parallel projection rely upon the technique of axonometry ("to measure along axes"), as described in Pohlke's theorem. In general, the resulting image is oblique (the rays are not perpendicular to the image plane); but in special cases the result is orthographic (the rays are perpendicular to the image plane). Axonometry should not be confused with axonometric projection, as in English literature the latter usually refers only to a specific class of pictorials (see below).

Orthographic projection

Main article: Orthographic projection See also: Geometric transformationThe orthographic projection is derived from the principles of descriptive geometry and is a two-dimensional representation of a three-dimensional object. It is a parallel projection (the lines of projection are parallel both in reality and in the projection plane). It is the projection type of choice for working drawings.

If the normal of the viewing plane (the camera direction) is parallel to one of the primary axes (which is the x, y, or z axis), the mathematical transformation is as follows; To project the 3D point , , onto the 2D point , using an orthographic projection parallel to the y axis (where positive y represents forward direction - profile view), the following equations can be used:

where the vector s is an arbitrary scale factor, and c is an arbitrary offset. These constants are optional, and can be used to properly align the viewport. Using matrix multiplication, the equations become:

While orthographically projected images represent the three dimensional nature of the object projected, they do not represent the object as it would be recorded photographically or perceived by a viewer observing it directly. In particular, parallel lengths at all points in an orthographically projected image are of the same scale regardless of whether they are far away or near to the virtual viewer. As a result, lengths are not foreshortened as they would be in a perspective projection.

Multiview projection

Main article: Multiview projection

With multiview projections, up to six pictures (called primary views) of an object are produced, with each projection plane parallel to one of the coordinate axes of the object. The views are positioned relative to each other according to either of two schemes: first-angle or third-angle projection. In each, the appearances of views may be thought of as being projected onto planes that form a 6-sided box around the object. Although six different sides can be drawn, usually three views of a drawing give enough information to make a 3D object. These views are known as front view, top view, and end view. The terms elevation, plan and section are also used.

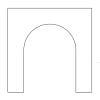

Oblique projection

Main article: Oblique projection Potting bench drawn in cabinet projection with an angle of 45° and a ratio of 2/3

Potting bench drawn in cabinet projection with an angle of 45° and a ratio of 2/3 Stone arch drawn in military perspective

Stone arch drawn in military perspective

In oblique projections the parallel projection rays are not perpendicular to the viewing plane as with orthographic projection, but strike the projection plane at an angle other than ninety degrees. In both orthographic and oblique projection, parallel lines in space appear parallel on the projected image. Because of its simplicity, oblique projection is used exclusively for pictorial purposes rather than for formal, working drawings. In an oblique pictorial drawing, the displayed angles among the axes as well as the foreshortening factors (scale) are arbitrary. The distortion created thereby is usually attenuated by aligning one plane of the imaged object to be parallel with the plane of projection thereby creating a true shape, full-size image of the chosen plane. Special types of oblique projections are:

Cavalier projection (45°)

In cavalier projection (sometimes cavalier perspective or high view point) a point of the object is represented by three coordinates, x, y and z. On the drawing, it is represented by only two coordinates, x″ and y″. On the flat drawing, two axes, x and z on the figure, are perpendicular and the length on these axes are drawn with a 1:1 scale; it is thus similar to the dimetric projections, although it is not an axonometric projection, as the third axis, here y, is drawn in diagonal, making an arbitrary angle with the x″ axis, usually 30 or 45°. The length of the third axis is not scaled.

Cabinet projection

The term cabinet projection (sometimes cabinet perspective) stems from its use in illustrations by the furniture industry. Like cavalier perspective, one face of the projected object is parallel to the viewing plane, and the third axis is projected as going off in an angle (typically 30° or 45° or arctan(2) = 63.4°). Unlike cavalier projection, where the third axis keeps its length, with cabinet projection the length of the receding lines is cut in half.

Military projection

A variant of oblique projection is called military projection. In this case, the horizontal sections are isometrically drawn so that the floor plans are not distorted and the verticals are drawn at an angle. The military projection is given by rotation in the xy-plane and a vertical translation an amount z.

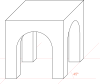

Axonometric projection

Main article: Axonometric projection

Axonometric projections show an image of an object as viewed from a skew direction in order to reveal all three directions (axes) of space in one picture. Axonometric projections may be either orthographic or oblique. Axonometric instrument drawings are often used to approximate graphical perspective projections, but there is attendant distortion in the approximation. Because pictorial projections innately contain this distortion, in instrument drawings of pictorials great liberties may then be taken for economy of effort and best effect.

Axonometric projection is further subdivided into three categories: isometric projection, dimetric projection, and trimetric projection, depending on the exact angle at which the view deviates from the orthogonal. A typical characteristic of orthographic pictorials is that one axis of space is usually displayed as vertical.

Isometric projection

In isometric pictorials (for methods, see Isometric projection), the direction of viewing is such that the three axes of space appear equally foreshortened, and there is a common angle of 120° between them. The distortion caused by foreshortening is uniform, therefore the proportionality of all sides and lengths are preserved, and the axes share a common scale. This enables measurements to be read or taken directly from the drawing.

Dimetric projection

In dimetric pictorials (for methods, see Dimetric projection), the direction of viewing is such that two of the three axes of space appear equally foreshortened, of which the attendant scale and angles of presentation are determined according to the angle of viewing; the scale of the third direction (vertical) is determined separately. Approximations are common in dimetric drawings.

Trimetric projection

In trimetric pictorials (for methods, see Trimetric projection), the direction of viewing is such that all of the three axes of space appear unequally foreshortened. The scale along each of the three axes and the angles among them are determined separately as dictated by the angle of viewing. Approximations in Trimetric drawings are common.

Limitations of parallel projection

See also: Impossible object An example of the limitations of isometric projection. The height difference between the red and blue balls cannot be determined locally.

An example of the limitations of isometric projection. The height difference between the red and blue balls cannot be determined locally. The Penrose stairs depicts a staircase which seems to ascend (anticlockwise) or descend (clockwise) yet forms a continuous loop.

The Penrose stairs depicts a staircase which seems to ascend (anticlockwise) or descend (clockwise) yet forms a continuous loop.

Objects drawn with parallel projection do not appear larger or smaller as they extend closer to or away from the viewer. While advantageous for architectural drawings, where measurements must be taken directly from the image, the result is a perceived distortion, since unlike perspective projection, this is not how our eyes or photography normally work. It also can easily result in situations where depth and altitude are difficult to gauge, as is shown in the illustration to the right.

In this isometric drawing, the blue sphere is two units higher than the red one. However, this difference in elevation is not apparent if one covers the right half of the picture, as the boxes (which serve as clues suggesting height) are then obscured.

This visual ambiguity has been exploited in op art, as well as "impossible object" drawings. M. C. Escher's Waterfall (1961), while not strictly utilizing parallel projection, is a well-known example, in which a channel of water seems to travel unaided along a downward path, only to then paradoxically fall once again as it returns to its source. The water thus appears to disobey the law of conservation of energy. An extreme example is depicted in the film Inception, where by a forced perspective trick an immobile stairway changes its connectivity. The video game Fez uses tricks of perspective to determine where a player can and cannot move in a puzzle-like fashion.

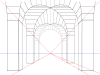

Perspective projection

See also: Perspective (graphical), Transformation matrix, and Camera matrix

Perspective projection or perspective transformation is a projection where three-dimensional objects are projected on a picture plane. This has the effect that distant objects appear smaller than nearer objects.

It also means that lines which are parallel in nature (that is, meet at the point at infinity) appear to intersect in the projected image. For example, if railways are pictured with perspective projection, they appear to converge towards a single point, called the vanishing point. Photographic lenses and the human eye work in the same way, therefore the perspective projection looks the most realistic. Perspective projection is usually categorized into one-point, two-point and three-point perspective, depending on the orientation of the projection plane towards the axes of the depicted object.

Graphical projection methods rely on the duality between lines and points, whereby two straight lines determine a point while two points determine a straight line. The orthogonal projection of the eye point onto the picture plane is called the principal vanishing point (P.P. in the scheme on the right, from the Italian term punto principale, coined during the renaissance).

Two relevant points of a line are:

- its intersection with the picture plane, and

- its vanishing point, found at the intersection between the parallel line from the eye point and the picture plane.

The principal vanishing point is the vanishing point of all horizontal lines perpendicular to the picture plane. The vanishing points of all horizontal lines lie on the horizon line. If, as is often the case, the picture plane is vertical, all vertical lines are drawn vertically, and have no finite vanishing point on the picture plane. Various graphical methods can be easily envisaged for projecting geometrical scenes. For example, lines traced from the eye point at 45° to the picture plane intersect the latter along a circle whose radius is the distance of the eye point from the plane, thus tracing that circle aids the construction of all the vanishing points of 45° lines; in particular, the intersection of that circle with the horizon line consists of two distance points. They are useful for drawing chessboard floors which, in turn, serve for locating the base of objects on the scene. In the perspective of a geometric solid on the right, after choosing the principal vanishing point —which determines the horizon line— the 45° vanishing point on the left side of the drawing completes the characterization of the (equally distant) point of view. Two lines are drawn from the orthogonal projection of each vertex, one at 45° and one at 90° to the picture plane. After intersecting the ground line, those lines go toward the distance point (for 45°) or the principal point (for 90°). Their new intersection locates the projection of the map. Natural heights are measured above the ground line and then projected in the same way until they meet the vertical from the map.

While orthographic projection ignores perspective to allow accurate measurements, perspective projection shows distant objects as smaller to provide additional realism.

Mathematical formula

The perspective projection requires a more involved definition as compared to orthographic projections. A conceptual aid to understanding the mechanics of this projection is to imagine the 2D projection as though the object(s) are being viewed through a camera viewfinder. The camera's position, orientation, and field of view control the behavior of the projection transformation. The following variables are defined to describe this transformation:

- – the 3D position of a point A that is to be projected.

- – the 3D position of a point C representing the camera.

- – The orientation of the camera (represented by Tait–Bryan angles).

- – the display surface's position relative to aforementioned .

Most conventions use positive z values (the plane being in front of the pinhole ), however negative z values are physically more correct, but the image will be inverted both horizontally and vertically. Which results in:

- – the 2D projection of

When and the 3D vector is projected to the 2D vector .

Otherwise, to compute we first define a vector as the position of point A with respect to a coordinate system defined by the camera, with origin in C and rotated by with respect to the initial coordinate system. This is achieved by subtracting from and then applying a rotation by to the result. This transformation is often called a camera transform, and can be expressed as follows, expressing the rotation in terms of rotations about the x, y, and z axes (these calculations assume that the axes are ordered as a left-handed system of axes):

This representation corresponds to rotating by three Euler angles (more properly, Tait–Bryan angles), using the xyz convention, which can be interpreted either as "rotate about the extrinsic axes (axes of the scene) in the order z, y, x (reading right-to-left)" or "rotate about the intrinsic axes (axes of the camera) in the order x, y, z (reading left-to-right)". If the camera is not rotated (), then the matrices drop out (as identities), and this reduces to simply a shift:

Alternatively, without using matrices (let us replace with and so on, and abbreviate to and to ):

This transformed point can then be projected onto the 2D plane using the formula (here, x/y is used as the projection plane; literature also may use x/z):

Or, in matrix form using homogeneous coordinates, the system

in conjunction with an argument using similar triangles, leads to division by the homogeneous coordinate, giving

The distance of the viewer from the display surface, , directly relates to the field of view, where is the viewed angle. (Note: This assumes that you map the points (-1,-1) and (1,1) to the corners of your viewing surface)

The above equations can also be rewritten as:

In which is the display size, is the recording surface size (CCD or Photographic film), is the distance from the recording surface to the entrance pupil (camera center), and is the distance, from the 3D point being projected, to the entrance pupil.

Subsequent clipping and scaling operations may be necessary to map the 2D plane onto any particular display media.

Weak perspective projection

A "weak" perspective projection uses the same principles of an orthographic projection, but requires the scaling factor to be specified, thus ensuring that closer objects appear bigger in the projection, and vice versa. It can be seen as a hybrid between an orthographic and a perspective projection, and described either as a perspective projection with individual point depths replaced by an average constant depth , or simply as an orthographic projection plus a scaling.

The weak-perspective model thus approximates perspective projection while using a simpler model, similar to the pure (unscaled) orthographic perspective. It is a reasonable approximation when the depth of the object along the line of sight is small compared to the distance from the camera, and the field of view is small. With these conditions, it can be assumed that all points on a 3D object are at the same distance from the camera without significant errors in the projection (compared to the full perspective model).

Equation

assuming focal length .

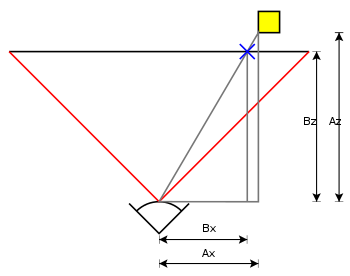

Diagram

To determine which screen x-coordinate corresponds to a point at multiply the point coordinates by:

where

- is the screen x coordinate

- is the model x coordinate

- is the focal length—the axial distance from the camera center to the image plane

- is the subject distance.

Because the camera is in 3D, the same works for the screen y-coordinate, substituting y for x in the above diagram and equation.

Alternatively, one could use clipping techniques, replacing the variables with values of the point that are out of the FOV-angle and the point inside Camera Matrix.

This technique, also known as "Inverse Camera", is a Perspective Projection Calculus with known values to calculate the last point on visible angle, projecting from the invisible point, after all needed transformations finished.

See also

- 3D computer graphics

- Camera matrix

- Computer graphics

- Cross section (geometry)

- Cross-sectional view

- Curvilinear perspective

- Cutaway drawing

- Descriptive geometry

- Engineering drawing

- Exploded-view drawing

- Homogeneous coordinates

- Homography

- Map projection (including Cylindrical projection)

- Multiview projection

- Perspective (graphical)

- Plan (drawing)

- Technical drawing

- Tesseract

- Texture mapping

- Transform, clipping, and lighting

- Video card

- Viewing frustum

- Virtual globe

References

- Treibergs, Andrejs. "The Geometry of Perspective Drawing on the Computer". University of Utah § Department of Mathematics. Archived from the original on Apr 30, 2015. Retrieved 24 April 2015.

- Mitchell, William; Malcolm McCullough (1994). Digital design media. John Wiley and Sons. p. 169. ISBN 978-0-471-28666-0.

- Maynard, Patric (2005). Drawing distinctions: the varieties of graphic expression. Cornell University Press. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-8014-7280-0.

- McReynolds, Tom; David Blythe (2005). Advanced graphics programming using openGL. Elsevier. p. 502. ISBN 978-1-55860-659-3.

- D. Hearn, & M. Baker (1997). Computer Graphics, C Version. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall], chapter 9

- James Foley (1997). Computer Graphics. Boston: Addison-Wesley. ISBN 0-201-84840-6], chapter 6

- Kirsti Andersen (2007), The geometry of an art, Springer, p. xxix, ISBN 9780387259611

- Ingrid Carlbom, Joseph Paciorek (1978). "Planar Geometric Projections and Viewing Transformations" (PDF). ACM Computing Surveys. 10 (4): 465–502. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.532.4774. doi:10.1145/356744.356750. S2CID 708008.

- Riley, K F (2006). Mathematical Methods for Physics and Engineering. Cambridge University Press. pp. 931, 942. ISBN 978-0-521-67971-8.

- Goldstein, Herbert (1980). Classical Mechanics (2nd ed.). Reading, Mass.: Addison-Wesley Pub. Co. pp. 146–148. ISBN 978-0-201-02918-5.

- Sonka, M; Hlavac, V; Boyle, R (1995). Image Processing, Analysis & Machine Vision (2nd ed.). Chapman and Hall. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-412-45570-4.

- Subhashis Banerjee (2002-02-18). "The Weak-Perspective Camera".

- Alter, T. D. (July 1992). 3D Pose from 3 Corresponding Points under Weak-Perspective Projection (PDF) (Technical report). MIT AI Lab.

Further reading

- Kenneth C. Finney (2004). 3D Game Programming All in One. Thomson Course. p. 93. ISBN 978-1-59200-136-1.

3D projection.

- Koehler; Ralph (December 2000). 2D/3D Graphics and Splines with Source Code. Author Solutions Incorporated. ISBN 978-0759611870.

External links

| Computer graphics | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Vector graphics | |||

| 2D graphics |

| ||

| 3D graphics | |||

| Concepts | |||

| Graphics software | |||

| Algorithms | |||

,

,  ,

,  onto the 2D point

onto the 2D point  ,

,  using an orthographic projection parallel to the y axis (where positive y represents forward direction - profile view), the following equations can be used:

using an orthographic projection parallel to the y axis (where positive y represents forward direction - profile view), the following equations can be used:

– the 3D position of a point A that is to be projected.

– the 3D position of a point A that is to be projected. – the 3D position of a point C representing the camera.

– the 3D position of a point C representing the camera. – The

– The  – the

– the  .

. – the 2D projection of

– the 2D projection of

and

and  the 3D vector

the 3D vector  is projected to the 2D vector

is projected to the 2D vector  .

.

as the position of point A with respect to a

as the position of point A with respect to a  with respect to the initial coordinate system. This is achieved by

with respect to the initial coordinate system. This is achieved by  and then applying a rotation by

and then applying a rotation by  to the result. This transformation is often called a camera transform, and can be expressed as follows, expressing the rotation in terms of rotations about the x, y, and z axes (these calculations assume that the axes are ordered as a

to the result. This transformation is often called a camera transform, and can be expressed as follows, expressing the rotation in terms of rotations about the x, y, and z axes (these calculations assume that the axes are ordered as a

), then the matrices drop out (as identities), and this reduces to simply a shift:

), then the matrices drop out (as identities), and this reduces to simply a shift:

with

with  and so on, and abbreviate

and so on, and abbreviate  to

to  and

and  to

to  ):

):

, directly relates to the field of view, where

, directly relates to the field of view, where  is the viewed angle. (Note: This assumes that you map the points (-1,-1) and (1,1) to the corners of your viewing surface)

is the viewed angle. (Note: This assumes that you map the points (-1,-1) and (1,1) to the corners of your viewing surface)

is the display size,

is the display size,  is the recording surface size (

is the recording surface size ( is the distance from the recording surface to the

is the distance from the recording surface to the  is the distance, from the 3D point being projected, to the entrance pupil.

is the distance, from the 3D point being projected, to the entrance pupil.

replaced by an average constant depth

replaced by an average constant depth  , or simply as an orthographic projection plus a scaling.

, or simply as an orthographic projection plus a scaling.

.

.

multiply the point coordinates by:

multiply the point coordinates by:

is the screen x coordinate

is the screen x coordinate is the model x coordinate

is the model x coordinate is the

is the  is the subject distance.

is the subject distance.