In muscle physiology, physiological cross-sectional area (PCSA) is the area of the cross section of a muscle perpendicular to its fibers, generally at its largest point. It is typically used to describe the contraction properties of pennate muscles. It is not the same as the anatomical cross-sectional area (ACSA), which is the area of the crossection of a muscle perpendicular to its longitudinal axis. In a non-pennate muscle the fibers are parallel to the longitudinal axis, and therefore PCSA and ACSA coincide.

Definition

One advantage of pennate muscles is that more muscle fibers can be packed in parallel, thus allowing the muscle to produce more force, although the fiber angle to the direction of action means that the maximum force in that direction is somewhat less than the maximum force in the fiber direction.

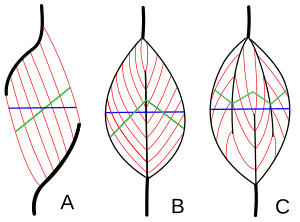

The muscle cross-sectional area (blue line in figure 1, also known as anatomical cross-section area, or ACSA) does not accurately represent the number of muscle fibers in the muscle. A better estimate is provided by the total area of the cross-sections perpendicular to the muscle fibers (green lines in figure 1). This measure is known as the physiological cross-sectional area (PCSA), and is commonly calculated and defined by the following formula, developed in 1975 by Alexander and Vernon:

where ρ is the density of the muscle:

PCSA increases with pennation angle, and with muscle length. In a pennate muscle, PCSA is always larger than ACSA. In a non-pennate muscle, it coincides with ACSA.

Estimating muscle force from PCSA

The total force exerted by the fibers in their oblique direction is proportional to PCSA. If the specific tension of the muscle fibers is known (force exerted by the fibers per unit of PCSA), it can be computed as follows:

However, only a component of that force can be used to pull the tendon in the desired direction. This component, which is the true muscle force (also called tendon force), is exerted along the direction of action of the muscle:

The other component, orthogonal to the direction of action of the muscle (Orthogonal force = Total force × sinΦ) is not exerted on the tendon, but simply squeezes the muscle, by pulling its aponeuroses toward each other.

Notice that, although it is practically convenient to compute PCSA based on volume or mass and fiber length, PCSA (and therefore the total fiber force, which is proportional to PCSA) is not proportional to muscle mass or fiber length alone. Namely, the maximum (tetanic) force of a muscle fiber simply depends on its thickness (cross-section area) and type. By no means it depends on its mass or length alone. For instance, when muscle mass increases due to physical development during childhood, this may be only due to an increase in length of the muscle fibers, with no change in fiber thickness (PCSA) or fiber type. In this case, an increase in mass does not produce an increase in force.

Sometimes, the increase in mass is associated with an increase in thickness. Only in this case it will have some effect on fiber force, but this effect will be proportional to the increase in thickness, not to the increase in mass. For instance, in some stages of physical development, the increase in mass may be due to both an increase in PCSA and in fiber length. Even in this case, muscle force does not increase as much as muscle mass does, because the mass increase is partly produced by a variation in fiber length, and fiber length has no effect on muscle force.

Alternative definition

In 1982 a different definition of PCSA, herein denoted PCSA2, to facilitate comparison with the previous definition, was introduced by Sacks & Roy:

The comparison shows that

in a pennate muscle, since is always smaller than 1, PCSA2 is always smaller than PCSA. Hence, it cannot be described as the total area of the cross-sections perpendicular to the muscle fibers (green lines in figure 1). It can be interpreted two ways:

- Projection of PCSA (green line in figure 1) on the anatomical cross-section plane (blue line).

- ACSA of a non-pennate muscle with the same force as the pennate muscle.

This implies that, in a muscle such as that in figure 1A, PCSA2 coincides with ACSA. The disadvantage of this definition is its more complex interpretation, its advantage is that muscle force can be computed more directly:

Currently, some authors keep using the original definition of PCSA, probably because of its intuitively appealing geometrical interpretation (figure 1).

References

- Strength and cross-sectional area of human skeletal muscle

- C. Gans (1982). Fiber architecture and muscle function. Exercise & Sports Science Reviews. 10:160–207.

- E. Otten (1988). Concepts and models of functional architecture in skeletal muscles. Exercise & Sports Science Reviews. 16:89–137.

- R. McN. Alexander, A. Vernon (1975). The dimension of knee and ankle muscles and the forces they exert, Journal of Human Movement Studies, 1:115–123.

- ^ Narici M.V., Landoni L., Minetti A.E. (1992). Assessment of human knee extensor muscles stress from in vivo physiological cross-sectional area and strength measurements. European Journal of Applied Physiology & Occupational Physiology. 65(5):438–444.

- ^ Maganaris C.N., Baltzopoulos V. (2000). In vivo mechanics of maximum isometric muscle contraction in man: Implications for modelling-based estimates of muscle specific tension. In Herzog W. (Ed). Skeletal muscle mechanics: from mechanisms to function. Wiley & Sons Ltd, p.267-288.

- ^ R.D. Sacks, R.R. Roy (1982). Architecture of The Hind Limb Muscles of Cats: Functional Significance. Journal of Morphology, 185–195.

- This is because the angle between the anatomical and physiological cross-section planes (angle between blue line and green line in figure 1) coincides with Φ, by definition.

- In a non-pennate muscle, ACSA = Muscle force / Specific tension, and Muscle force = PCSA2 × Specific tension, hence PCSA2 = Muscle force / Specific tension = ACSA.

| Muscle tissue | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smooth muscle | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Striated muscle |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

is always smaller than 1, PCSA2 is always smaller than PCSA. Hence, it cannot be described as the total area of the cross-sections perpendicular to the muscle fibers (green lines in figure 1). It can be interpreted two ways:

is always smaller than 1, PCSA2 is always smaller than PCSA. Hence, it cannot be described as the total area of the cross-sections perpendicular to the muscle fibers (green lines in figure 1). It can be interpreted two ways: