| This article includes a list of references, related reading, or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations. Please help improve this article by introducing more precise citations. (November 2024) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

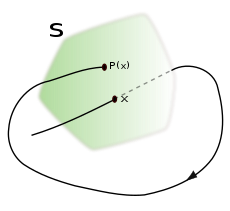

In mathematics, particularly in dynamical systems, a first recurrence map or Poincaré map, named after Henri Poincaré, is the intersection of a periodic orbit in the state space of a continuous dynamical system with a certain lower-dimensional subspace, called the Poincaré section, transversal to the flow of the system. More precisely, one considers a periodic orbit with initial conditions within a section of the space, which leaves that section afterwards, and observes the point at which this orbit first returns to the section. One then creates a map to send the first point to the second, hence the name first recurrence map. The transversality of the Poincaré section means that periodic orbits starting on the subspace flow through it and not parallel to it.

A Poincaré map can be interpreted as a discrete dynamical system with a state space that is one dimension smaller than the original continuous dynamical system. Because it preserves many properties of periodic and quasiperiodic orbits of the original system and has a lower-dimensional state space, it is often used for analyzing the original system in a simpler way. In practice this is not always possible as there is no general method to construct a Poincaré map.

A Poincaré map differs from a recurrence plot in that space, not time, determines when to plot a point. For instance, the locus of the Moon when the Earth is at perihelion is a recurrence plot; the locus of the Moon when it passes through the plane perpendicular to the Earth's orbit and passing through the Sun and the Earth at perihelion is a Poincaré map. It was used by Michel Hénon to study the motion of stars in a galaxy, because the path of a star projected onto a plane looks like a tangled mess, while the Poincaré map shows the structure more clearly.

Definition

Let (R, M, φ) be a global dynamical system, with R the real numbers, M the phase space and φ the evolution function. Let γ be a periodic orbit through a point p and S be a local differentiable and transversal section of φ through p, called a Poincaré section through p.

Given an open and connected neighborhood of p, a function

is called Poincaré map for the orbit γ on the Poincaré section S through the point p if

- P(p) = p

- P(U) is a neighborhood of p and P:U → P(U) is a diffeomorphism

- for every point x in U, the positive semi-orbit of x intersects S for the first time at P(x)

Example

Consider the following system of differential equations in polar coordinates, :

The flow of the system can be obtained by integrating the equation: for the component we simply have while for the component we need to separate the variables and integrate:

Inverting last expression gives

and since

we find

The flow of the system is therefore

The behaviour of the flow is the following:

- The angle increases monotonically and at constant rate.

- The radius tends to the equilibrium for every value.

Therefore, the solution with initial data draws a spiral that tends towards the radius 1 circle.

We can take as Poincaré section for this flow the positive horizontal axis, namely : obviously we can use as coordinate on the section. Every point in returns to the section after a time (this can be understood by looking at the evolution of the angle): we can take as Poincaré map the restriction of to the section computed at the time , . The Poincaré map is therefore :

The behaviour of the orbits of the discrete dynamical system is the following:

- The point is fixed, so for every .

- Every other point tends monotonically to the equilibrium, for .

Poincaré maps and stability analysis

Poincaré maps can be interpreted as a discrete dynamical system. The stability of a periodic orbit of the original system is closely related to the stability of the fixed point of the corresponding Poincaré map.

Let (R, M, φ) be a differentiable dynamical system with periodic orbit γ through p. Let

be the corresponding Poincaré map through p. We define

and

then (Z, U, P) is a discrete dynamical system with state space U and evolution function

Per definition this system has a fixed point at p.

The periodic orbit γ of the continuous dynamical system is stable if and only if the fixed point p of the discrete dynamical system is stable.

The periodic orbit γ of the continuous dynamical system is asymptotically stable if and only if the fixed point p of the discrete dynamical system is asymptotically stable.

See also

References

- Teschl, Gerald. Ordinary Differential Equations and Dynamical Systems. Providence: American Mathematical Society.

External links

- Shivakumar Jolad, Poincare Map and its application to 'Spinning Magnet' problem, (2005)

of p, a

of p, a

:

:

component we simply have

component we simply have

while for the

while for the  component we need to separate the variables and integrate:

component we need to separate the variables and integrate:

for every value.

for every value. draws a spiral that tends towards the radius 1 circle.

draws a spiral that tends towards the radius 1 circle.

: obviously we can use

: obviously we can use  returns to the section after a time

returns to the section after a time  (this can be understood by looking at the evolution of the angle): we can take as Poincaré map the restriction of

(this can be understood by looking at the evolution of the angle): we can take as Poincaré map the restriction of  to the section

to the section  ,

,  .

The Poincaré map is therefore :

.

The Poincaré map is therefore :

is the following:

is the following:

is fixed, so

is fixed, so  for every

for every  .

. for

for  .

.