In optics, polarization mixing refers to changes in the relative strengths of the Stokes parameters caused by reflection or scattering—see vector radiative transfer—or by changes in the radial orientation of the detector.

Example: A sloping, specular surface

The definition of the four Stokes components are, in a fixed basis:

where Ev and Eh are the electric field components in the vertical and horizontal directions respectively. The definitions of the coordinate bases are arbitrary and depend on the orientation of the instrument. In the case of the Fresnel equations, the bases are defined in terms of the surface, with the horizontal being parallel to the surface and the vertical in a plane perpendicular to the surface.

When the bases are rotated by 45 degrees around the viewing axis, the definition of the third Stokes component becomes equivalent to that of the second, that is the difference in field intensity between the horizontal and vertical polarizations. Thus, if the instrument is rotated out of plane from the surface upon which it is looking, this will give rise to a signal. The geometry is illustrated in the above figure: is the instrument viewing angle with respect to nadir, is the viewing angle with respect to the surface normal and is the angle between the polarisation axes defined by the instrument and that defined by the Fresnel equations, i.e., the surface.

Ideally, in a polarimetric radiometer, especially a satellite mounted one, the polarisation axes are aligned with the Earth's surface, therefore we define the instrument viewing direction using the following vector:

We define the slope of the surface in terms of the normal vector, , which can be calculated in a number of ways. Using angular slope and azimuth, it becomes:

where is the slope and is the azimuth relative to the instrument view. The effective viewing angle can be calculated via a dot product between the two vectors:

from which we compute the reflection coefficients, while the angle of the polarisation plane can be calculated with cross products:

where is the unit vector defining the y-axis.

The angle, , defines the rotation of the polarization axes between those defined for the Fresnel equations versus those of the detector. It can be used to correct for polarization mixing caused by a rotated detector, or to predict what the detector "sees", especially in the third Stokes component. See Stokes parameters#Relation to the polarization ellipse.

Application: Aircraft radiometry data

The Pol-Ice 2007 campaign included measurements over sea ice and open water from a fully polarimetric, aeroplane-mounted, L-band (1.4 GHz) radiometer. Since the radiometer was fixed to the aircraft, changes in aircraft attitude are equivalent to changes in surface slope. Moreover, emissivity over calm water and to a lesser extent, sea ice, can be effectively modelled using the Fresnel equations. Thus this is an excellent source of data with which to test the ideas discussed in the previous section. In particular, the campaign included both circular and zig-zagging overflights which will produce strong mixing in the Stokes parameters.

Correcting or removing bad data

Without filtering.

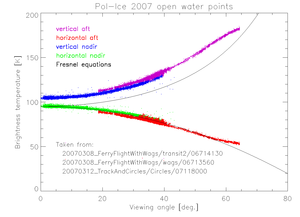

Without filtering. All points with significant polarization mixing have been removed.Comparison of aircraft radiometry data over water with an emissivity model based on the Fresnel equations.

All points with significant polarization mixing have been removed.Comparison of aircraft radiometry data over water with an emissivity model based on the Fresnel equations.

To test the calibration of the EMIRAD II radiometer used in the Pol-Ice campaign, measurements over open water were compared with model results based on the Fresnel equations. The first plot, which compares the measured data with the model, shows that vertically polarized channel is too high, but more importantly in this context, are the smeared points in between the otherwise relatively clean function for measured vertical and horizontal brightness temperature as a function of viewing angle. These are the result of polarization mixing caused by changes in the attitude of the aircraft, particularly the roll angle. Since there are plenty of data points, rather than correcting the bad data, the authors simply exclude points for which the angle, , is too large. The result is shown at far right.

Predicting U

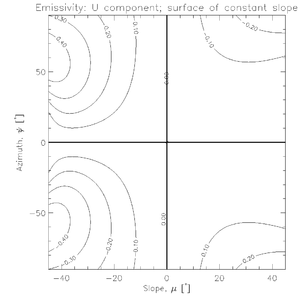

Dependence of eU on surface-slope and azimuth-angle for a refractive index of 2 and a nominal instrument pointing-angle of 45 degrees.

Dependence of eU on surface-slope and azimuth-angle for a refractive index of 2 and a nominal instrument pointing-angle of 45 degrees. Modelled U versus Pol-Ice field data for a circular overflight over sea ice.

Modelled U versus Pol-Ice field data for a circular overflight over sea ice.

Many of the radiance measurements over sea ice included large signals in the third Stoke component, U. It turns out that these can be predicted to fairly high accuracy simply from the aircraft attitude. We use the following model for emissivity in U:

where eh and ev are the emissivities calculated via the Fresnel or similar equations and eU is the emissivity in U—that is, , where T is physical temperature—for the rotated polarization axes. The plot below shows the dependence on surface-slope and azimuth angle for a refractive index of 2 (a common value for sea ice) and a nominal instrument pointing-angle of 45 degrees. Using the same model, we can simulate the U-component of the Stokes vector for the radiometer.

See also

References

- ^ G. Heygster; S. Hendricks; L. Kaleschke; N. Maass; et al. (2009). L-Band Radiometry for Sea-Ice Applications (Technical report). Institute of Environmental Physics, University of Bremen. ESA/ESTEC Contract N. 21130/08/NL/EL.

- ^ Mills, Peter; Heygster, Georg (2011). "Sea ice emissivity modelling at L-band and application to Pol-Ice campaign field data" (PDF). IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing. 49 (in press): 612. Bibcode:2011ITGRS..49..612M. doi:10.1109/TGRS.2010.2060729. S2CID 20981849.

- N. Skou; S. S. Sobjaerg & J. Balling (2007). EMIRAD-2 and its use in the CoSMOS Campaigns (Technical report). Electromagnetic Systems Section Danish National Space Center, Technical University of Denmark. ESTEC Contract No. 18924/05/NL/FF.

- M. R. Vant; R. O. Ramseier & V. Makios (1978). "The complex-dielectric constant of sea ice at frequencies in the range 0.1-4.0 GHz". Journal of Applied Physics. 49 (3): 1246–1280. Bibcode:1978JAP....49.1264V. doi:10.1063/1.325018.

is the instrument viewing angle with respect to nadir,

is the instrument viewing angle with respect to nadir,  is the viewing angle with respect to the surface normal and

is the viewing angle with respect to the surface normal and  is the angle between the polarisation axes defined by the instrument and that defined by the Fresnel equations, i.e., the surface.

is the angle between the polarisation axes defined by the instrument and that defined by the Fresnel equations, i.e., the surface.

, which can be calculated in a number of ways. Using angular slope and azimuth, it becomes:

, which can be calculated in a number of ways. Using angular slope and azimuth, it becomes:

is the slope and

is the slope and  is the azimuth relative to the instrument view. The effective viewing angle can be

calculated via a

is the azimuth relative to the instrument view. The effective viewing angle can be

calculated via a

is the unit vector defining the y-axis.

is the unit vector defining the y-axis.

, where T is physical temperature—for the rotated polarization axes. The plot below shows the dependence on surface-slope and

, where T is physical temperature—for the rotated polarization axes. The plot below shows the dependence on surface-slope and