| Mathematical analysis → Complex analysis |

| Complex analysis |

|---|

|

| Complex numbers |

| Complex functions |

| Basic theory |

| Geometric function theory |

| People |

In complex analysis (a branch of mathematics), a pole is a certain type of singularity of a complex-valued function of a complex variable. It is the simplest type of non-removable singularity of such a function (see essential singularity). Technically, a point z0 is a pole of a function f if it is a zero of the function 1/f and 1/f is holomorphic (i.e. complex differentiable) in some neighbourhood of z0.

A function f is meromorphic in an open set U if for every point z of U there is a neighborhood of z in which at least one of f and 1/f is holomorphic.

If f is meromorphic in U, then a zero of f is a pole of 1/f, and a pole of f is a zero of 1/f. This induces a duality between zeros and poles, that is fundamental for the study of meromorphic functions. For example, if a function is meromorphic on the whole complex plane plus the point at infinity, then the sum of the multiplicities of its poles equals the sum of the multiplicities of its zeros.

Definitions

A function of a complex variable z is holomorphic in an open domain U if it is differentiable with respect to z at every point of U. Equivalently, it is holomorphic if it is analytic, that is, if its Taylor series exists at every point of U, and converges to the function in some neighbourhood of the point. A function is meromorphic in U if every point of U has a neighbourhood such that at least one of f and 1/f is holomorphic in it.

A zero of a meromorphic function f is a complex number z such that f(z) = 0. A pole of f is a zero of 1/f.

If f is a function that is meromorphic in a neighbourhood of a point of the complex plane, then there exists an integer n such that

is holomorphic and nonzero in a neighbourhood of (this is a consequence of the analytic property). If n > 0, then is a pole of order (or multiplicity) n of f. If n < 0, then is a zero of order of f. Simple zero and simple pole are terms used for zeroes and poles of order Degree is sometimes used synonymously to order.

This characterization of zeros and poles implies that zeros and poles are isolated, that is, every zero or pole has a neighbourhood that does not contain any other zero and pole.

Because of the order of zeros and poles being defined as a non-negative number n and the symmetry between them, it is often useful to consider a pole of order n as a zero of order –n and a zero of order n as a pole of order –n. In this case a point that is neither a pole nor a zero is viewed as a pole (or zero) of order 0.

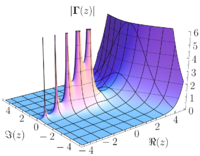

A meromorphic function may have infinitely many zeros and poles. This is the case for the gamma function (see the image in the infobox), which is meromorphic in the whole complex plane, and has a simple pole at every non-positive integer. The Riemann zeta function is also meromorphic in the whole complex plane, with a single pole of order 1 at z = 1. Its zeros in the left halfplane are all the negative even integers, and the Riemann hypothesis is the conjecture that all other zeros are along Re(z) = 1/2.

In a neighbourhood of a point a nonzero meromorphic function f is the sum of a Laurent series with at most finite principal part (the terms with negative index values):

where n is an integer, and Again, if n > 0 (the sum starts with , the principal part has n terms), one has a pole of order n, and if n ≤ 0 (the sum starts with , there is no principal part), one has a zero of order .

At infinity

A function is meromorphic at infinity if it is meromorphic in some neighbourhood of infinity (that is outside some disk), and there is an integer n such that

exists and is a nonzero complex number.

In this case, the point at infinity is a pole of order n if n > 0, and a zero of order if n < 0.

For example, a polynomial of degree n has a pole of degree n at infinity.

The complex plane extended by a point at infinity is called the Riemann sphere.

If f is a function that is meromorphic on the whole Riemann sphere, then it has a finite number of zeros and poles, and the sum of the orders of its poles equals the sum of the orders of its zeros.

Every rational function is meromorphic on the whole Riemann sphere, and, in this case, the sum of orders of the zeros or of the poles is the maximum of the degrees of the numerator and the denominator.

Examples

- The function

- is meromorphic on the whole Riemann sphere. It has a pole of order 1 or simple pole at and a simple zero at infinity.

- The function

- is meromorphic on the whole Riemann sphere. It has a pole of order 2 at and a pole of order 3 at . It has a simple zero at and a quadruple zero at infinity.

- The function

- is meromorphic in the whole complex plane, but not at infinity. It has poles of order 1 at . This can be seen by writing the Taylor series of around the origin.

- The function

- has a single pole at infinity of order 1, and a single zero at the origin.

All above examples except for the third are rational functions. For a general discussion of zeros and poles of such functions, see Pole–zero plot § Continuous-time systems.

Function on a curve

The concept of zeros and poles extends naturally to functions on a complex curve, that is complex analytic manifold of dimension one (over the complex numbers). The simplest examples of such curves are the complex plane and the Riemann surface. This extension is done by transferring structures and properties through charts, which are analytic isomorphisms.

More precisely, let f be a function from a complex curve M to the complex numbers. This function is holomorphic (resp. meromorphic) in a neighbourhood of a point z of M if there is a chart such that is holomorphic (resp. meromorphic) in a neighbourhood of Then, z is a pole or a zero of order n if the same is true for

If the curve is compact, and the function f is meromorphic on the whole curve, then the number of zeros and poles is finite, and the sum of the orders of the poles equals the sum of the orders of the zeros. This is one of the basic facts that are involved in Riemann–Roch theorem.

See also

- Argument principle

- Control theory § Stability

- Filter design

- Filter (signal processing)

- Gauss–Lucas theorem

- Hurwitz's theorem (complex analysis)

- Marden's theorem

- Nyquist stability criterion

- Pole–zero plot

- Residue (complex analysis)

- Rouché's theorem

- Sendov's conjecture

References

- Conway, John B. (1986). Functions of One Complex Variable I. Springer. ISBN 0-387-90328-3.

- Conway, John B. (1995). Functions of One Complex Variable II. Springer. ISBN 0-387-94460-5.

- Henrici, Peter (1974). Applied and Computational Complex Analysis 1. John Wiley & Sons.

of the

of the

of f. Simple zero and simple pole are terms used for zeroes and poles of order

of f. Simple zero and simple pole are terms used for zeroes and poles of order  Degree is sometimes used synonymously to order.

Degree is sometimes used synonymously to order.

a nonzero meromorphic function f is the sum of a

a nonzero meromorphic function f is the sum of a

Again, if n > 0 (the sum starts with

Again, if n > 0 (the sum starts with  , the principal part has n terms), one has a pole of order n, and if n ≤ 0 (the sum starts with

, the principal part has n terms), one has a pole of order n, and if n ≤ 0 (the sum starts with  , there is no principal part), one has a zero of order

, there is no principal part), one has a zero of order  is meromorphic at infinity if it is meromorphic in some neighbourhood of infinity (that is outside some

is meromorphic at infinity if it is meromorphic in some neighbourhood of infinity (that is outside some

and a simple zero at infinity.

and a simple zero at infinity.

and a pole of order 3 at

and a pole of order 3 at  . It has a simple zero at

. It has a simple zero at  and a quadruple zero at infinity.

and a quadruple zero at infinity.

. This can be seen by writing the

. This can be seen by writing the  around the origin.

around the origin.

such that

such that  is holomorphic (resp. meromorphic) in a neighbourhood of

is holomorphic (resp. meromorphic) in a neighbourhood of  Then, z is a pole or a zero of order n if the same is true for

Then, z is a pole or a zero of order n if the same is true for