This article is about the percentage of the population that have undergone FGM. For laws concerning female genital mutilation, see Female genital mutilation laws by country.

Female genital mutilation (FGM), also known as female genital cutting (FGC), female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C) and female circumcision, is practiced in 30 countries in western, eastern, and north-eastern Africa, in parts of the Middle East and Asia, and within some immigrant communities in Europe, North America and Australia, as well as in specific minority enclaves in areas such as South Asia and Russia. The WHO defines the practice as "all procedures that involve partial or total removal of the external female genitalia, or other injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons."

In a 2013 UNICEF report covering 29 countries in Africa and the Middle East, Egypt had the region's highest total number of women that have undergone FGM (27 million), while Somalia had the highest percentage (prevalence) of FGM (98%).

The world's first known campaign against FGM took place in Egypt in the 1920s. FGM prevalence in Egypt in 1995 was still at least as high as Somalia's 2013 world record (98%), despite dropping significantly since then among young women. Estimates of the prevalence of FGM vary according to source.

Classifications of FGM

Main article: Female genital mutilationThe WHO identifies four types of FGM:

- Type I: removal of the clitoral hood, the skin around the clitoris (Ia), with partial or complete removal of the clitoris (Ib)

- Type II: removal of the labia minora (IIa), with partial or complete removal of the clitoris (IIb) and the labia majora (IIc)

- Type III: removal of all or part of the labia minora (IIIa) and labia majora (IIIb), complete removal of the clitoris, and the stitching of a seal across the vagina, leaving a small opening for the passage of urine and menstrual blood (infibulation)

- Type IV: other miscellaneous acts, might or might not include cauterization of the clitoris, cutting of the vagina (gishiri cutting), and introducing corrosive substances into the vagina to tighten it (extreme and rare cases)

Prevalence

The term "prevalence" is used to describe the proportion of women and girls now living in a country who have undergone FGM at some stage in their lives. This is distinct from the "incidence" of FGM which describes the proportion of women and girls who have undergone the procedure within a particular time period, which could be contemporary or historical. FGM is practiced in some but not all African countries, the Middle East, Indonesia and Malaysia, as well as some migrants in Europe, United States and Australia. It is also seen in some populations of South Asia. The highest known prevalence rates are in 30 African countries, in a band that stretches from Senegal in West Africa to Ethiopia on the east coast, as well as from Egypt in the north to Tanzania in the south.

In a 2013 UNICEF report based on surveys completed by select countries, FGM is known to be prevalent in 27 African countries, Yemen and Iraqi Kurdistan, where 125 million women and girls have undergone FGM. The UNICEF report notes FGM is found in countries beyond the 29 countries it covered, and the total worldwide number is unknown.

Other reports claim the prevalence of FGM in countries not discussed by the 2013 UNICEF report. The practice occurs in Jordan, Iraq, Syria, Oman, United Arab Emirates and Qatar. Earlier reports claimed the prevalence of FGM in Israel among the Negev Bedouin, which by 2009 has virtually disappeared.

As a result of immigration, FGM has also spread to Europe, Australia, and the United States, with some families having their daughters undergo the procedure while on vacation overseas . As Western governments become more aware of FGM, legislation has come into effect in many countries to make the practice a criminal offense. In 2006, Khalid Adem became the first man in the United States to be prosecuted for mutilating his daughter.

The United Nations has called for elimination of the practice by 2030. A 2017 UCLA Fielding School of Public Health study, measuring trends in the prevalence of FGM over the course of three decades, found that they dropped significantly in 17 of the 22 countries surveyed. The researchers found a 2–8 percentage points increase in Chad, Mali and Sierra Leone during the 30-years period.

Data reliability

Much of the FGM prevalence data currently available is based on verbal surveys and self-reporting. Clinical examinations are uncommon. The assumption is that women respond truthfully when asked about their FGM status and that they know the type and extent of FGM that was performed on their genitalia. Many FGM procedures are performed at a very young age, many cultures feel a taboo about such discussions, and a number of such factors raise the possibility that the validity of survey responses might be incorrect, potentially underreported. In Oman, for example, some do not wish to discuss FGM from the fear that such discussion is showing their culture's dirty laundry to the world, causing criticism of a practice that they believe is purely religious.

In countries where FGM has been outlawed, fear of prosecution of family members or self, and social disapproval from elders may cause women to deny that they underwent or were subjected to FGM. For example, the self-reported circumcision status of women aged 15–49 was verbally surveyed in 1995 in northern Ghana. The same women were interviewed again in 2000 after the enactment of a law that criminalized FGM and Ghana-wide public campaigns against the practice. This study discovered that 13% of women who reported in 1995 that they had undergone FGM denied it in the 2000 interview, with youngest age group girls denying at rates as high as 50%.

UNICEF has revised its data on the FGM prevalence rates in the Kurdistan region of the Middle East:

Where is FGM/C practiced? There are reports, but no clear evidence, of a limited incidence in (..) certain Kurdish communities in Iraq.

— UNICEF (2005),

Female Genital Mutilation or Cutting (FGM/C): 1 in 2 young girls (15–24) has experienced FGM/C when they were younger in Erbil and Sulaymaniyah governorates (Kurdistan Region).

— UNICEF (2011),

Africa

In July 2003, at its second summit, the African Union adopted the Maputo Protocol promoting women's rights and calling for an end to FGM. The agreement came into force in November 2005, and by December 2008, 25 member countries had ratified it.

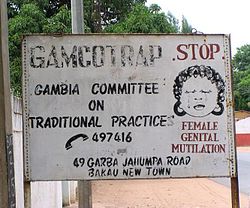

As of 2013, according to a UNICEF report, 24 African countries have legislations or decrees against FGM/C practice; these countries are: Benin, Burkina Faso, Central African Republic, Chad, Côte d'Ivoire, Djibouti, Egypt, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Kenya, Mauritania, Niger, Nigeria (since 2015), Senegal, Somalia, Sudan (some states), Tanzania, Togo and Uganda (see page 9 of the report) and Zambia and South Africa (see page 8). In 2015, Gambia's president Yahya Jammeh banned FGM.

In 2014 The Girl Generation, an African-led campaign to oppose FGM worldwide, was launched.

General

Although estimates of the prevalence of FGM vary, sources have consistently found the practice to be undergone by the majority of women in the Horn of Africa, in the West African countries of Guinea, Sierra Leone, Gambia, Mauritania, Mali and Burkina Faso, as well as in Sudan and Egypt. Of these countries, all have laws or decrees against the practice, with the exception of Sierra Leone, Mali and some states of Sudan.

Infibulation

Infibulation, the most extreme form of FGM, known also as Type III, is practiced primarily in countries located in northeastern Africa.

The practice is the removal of the inner and outer labia, and the suturing of the vulva. It is mostly practiced in northeastern Africa, particularly Djibouti, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Somalia and Sudan.

The procedure leaves a wall of skin and flesh across the vagina and the rest of the pubic area. By inserting a twig or similar object before the wound heals, a small hole is created for the passage of urine and menstrual blood. The procedure is usually accompanied by the removal of the clitoral glans. The legs are bound together for two to four weeks(up to 40 days) to allow healing.

The vagina is usually penetrated at the time of a woman's marriage by her husband's penis, or by cutting the tissue with a knife. The vagina is opened further for childbirth, and usually closed again afterwards, a process known as defibulation (or deinfibulation) and reinfibulation. Infibulation can cause chronic pain and infection, organ damage, prolonged micturition, urinary incontinence, inability to get pregnant, difficulty giving birth, obstetric fistula and fatal bleeding.

Algeria

FGM is not generally practiced in Algeria, but is present among immigrants in South Algeria, particularly among Sub-Saharan African migrants. It is considered a criminal offense and is punishable by up to 25 years in prison.

Benin

Female genital mutilation is present in Benin. According to a 2011–12 survey, 7.3% of the women in Benin have been subjected to FGM. This is a decline over the 2001 survey, which reported 16.8%. As of 2018, UNICEF's latest data, from 2014, confirms only 0.2% of Benin girls aged 0 to 14 had been subjected to FGM, while 9% of females aged 15 to 49 had so. The prevalence varies with religion in Benin; FGM is prevalent in 49% of Muslim women. The prevalence in other groups is lower, 3% of traditional religions, 3% of Roman Catholic and 1% in other Christian women. A 2003 law bans all forms of FGM. According to UNICEF, Benin experienced the most dramatic decline in low prevalence countries, from 8% in 2006 to 2% in 2012, a 75% decline.

Burkina Faso

The UNFPA gives a prevalence of 76% for the year of 2021 (women aged from 15 to 49) in Burkina Faso. A 1998 survey reported a lower rate of 72%. This was not considered as evidence of an increase in the practice, but as reflecting the worldwide fact that better and more information is increasingly available on FGM. As of 2018, UNICEF's latest data, from 2010, confirms only 13% of girls aged 0 to 14 had been subjected to FGM, while 76% of females aged 15 to 49 had so. The prevalence varies with religion in Burkina Faso. FGM is prevalent in 82% of Muslim women, 73% of traditional religions, 66% of Roman Catholics and 60% of Protestants.

In a 2011 study on a wide range of variables, FGM prevalence characteristics in Burkina Faso was found to be strongly associated with religion, and age being the other important variable. A law prohibiting FGM was enacted in 1996 and went into effect in February 1997. Even before this law a presidential decree had set up the National Committee against excision and imposed fines on people guilty of excising girls and women. The new law includes stricter punishment. Several women excising girls have been handed prison sentences. Burkina Faso ratified the Maputo Protocol in 2006.

Cameroon

Female genital mutilation is rare in Cameroon, being concentrated in the far north and the southwest of the country. In a 2004 study, the FGM prevalence rate was 1.4%. Even though national rate is low, there are regions with high prevalence rate. In extreme north Cameroon, the prevalence rate is 13% for the Fulbe people and people of Arab descent. The prevalence varies with religion; FGM is prevalent in 6% of Muslim women, less than 1% of Christians, and 0% for Animist women. Cameroon's national penal code does not classify genital mutilation as a criminal offence. Article 277 criminalizes aggravated assault, including aggravated assault to organs. A draft law has been pending for over 10 years.

Central African Republic

WHO gives the prevalence of FGM in Central African Republic at 24.2% in 2010. A survey from 2000 found FGM was prevalent in 36% of Central African Republic women. This is a decline over the 1994 survey, which reported 43%. The prevalence in the 2000 survey varied with religion in Central African Republic; FGM was prevalent in 46% of Animist women, 39% of Muslim, 36% of Protestants, and 35% of Catholic women.

In 1996, the President issued an Ordinance prohibiting FGM throughout the country. It has the force of national law. Any violation of the Ordinance is punishable by imprisonment of from one month and one day to two years and a fine of 5,100 to 100,000 francs (approximately US$8–160). No arrests are known to have been made under the law. As FGM is less prevalent among younger women according to City University London in 2015, this suggested a decline in the practice.

Chad

In Chad's first survey on FGM in 2004, FGM prevalence rate was 45%. A later UNICEF survey in 2014–2015 reported 38.4% FGM prevalence amongst women and girls aged 15 to 49, and 10% amongst girls 14-years old or younger. The prevalence varies with religion in Chad; FGM is prevalent in 61% of Muslim women, 31% of Catholics, 16% of Protestants, and 12% of traditional religions. The prevalence also varies with ethnic groups; the Arabs (95%), Hadjarai (94%), Ouadai (91%) and Fitri-batha (86%), and less than 2.5% among the Gorane, Tandjile and Mayo-Kebbi. Law no 6/PR/2002 on the promotion of reproductive health has provisions prohibiting FGM, but does not provide for sanctions. FGM may be punished under existing laws against assault, wounding, and mutilation of the body.

Comoros

Female genital mutilation is officially discouraged in Comoros.

Côte d'Ivoire

As of 2018, UNICEF's latest data, from 2016, reports 10% of Ivory Coast girls aged 0 to 14 had been subjected to FGM, while 37% of females aged 15 to 49 had so. The latter figure is practically unchanged from a prior 2006 survey, in which the prevalence of FGM was reported at 36.4% among women there aged 15–49. A 2005 survey found that 42% of all women aged between 15 and 49 had been subjected to FGM. This is similar to the FGM reported rate of 46% in 1998 and 43% in 1994. The prevalence varies with religion in Côte d'Ivoire; FGM is prevalent in 76% of Muslim women, 45% of Animist, 14% of Catholic and 13% of Protestant women. A 1998 law provides that harm to the integrity of the genital organ of a woman by complete or partial removal, excision, desensitization or by any other procedure will, if harmful to a woman's health, be punishable by imprisonment of one to five years and a fine of 360,000 to two million CFA Francs (approximately US$576–3,200). The penalty is five to twenty years incarceration if a death occurs during the procedure and up to five years' prohibition of medical practice, if this procedure is carried out by a doctor.

Democratic Republic of the Congo

Female genital mutilation in the Democratic Republic of the Congo is rare, but it takes place among some populations in northern parts of the country. FGM is illegal: the law imposes a penalty of two to five years of prison and a fine of 200,000 Congolese francs on any person who violates the "physical or functional integrity" of the genital organs. The prevalence of FGM is estimated at 5% of women in the country. Type II is usually performed.

Djibouti

Estimates for FGM prevalence rate of FGM in Djibouti range from 93% to 98%. In a UNICEF 2010 report, Djibouti has the world's second highest rate of Type III FGM, with about two thirds of all Djibouti women undergoing the procedure; Type I is the next most common form of female circumcision practiced in the country. Like its neighboring countries, a large percentage of women in Djibouti also undergo re-infibulation after birth or a divorce.

Two thirds of the women claimed tradition and religion as the primary motivation for undergoing FGM. A predominantly Muslim country, Islamic clerics in Djibouti have been divided on the FGM issue, with some actively supporting the practice and others opposing it. FGM was outlawed in the country's revised Penal Code that went into effect in April 1995. Article 333 of the Penal Code provides that persons found guilty of this practice will face a five-year prison term and a fine of one million Djibouti francs (approximately US$5,600). Djibouti ratified the Maputo Protocol in 2005.

Egypt

As of 2018, UNICEF's latest data, from 2015, reports 14% of Egyptian girls aged 0 to 14 had been subjected to FGM, while 87% of females aged 15 to 49 had so. This is down from a previous 2008 study that reported the prevalence at 91%. The 2016 UNICEF report stated that the share of girls aged 15 to 19 who had undergone FGM dropped from 97% in 1985 to 70% in 2015. The percentage of girls and women aged 15 to 49 years who had undergone FGM in the years 2004–2015 was 87%, while girls aged 0 to 14 years who had undergone FGM in the years 2010–2015 numbered 14%. Earlier, a study in 2000 found that 97% of Egypt's population practiced FGM and a 2005 study found that over 95% of Egyptian women have undergone some form of FGM. 38% of girls and women aged 15 to 49 years who had heard about FGM thought the practice should end, while 28% of the boys and men those ages did.

Although it has had limited effect, Egypt's Ministry of Health and Population has banned all forms of female genital mutilation since 2007. The ministry's order declared it is "prohibited for any doctors, nurses, or any other person to carry out any cut of, flattening or modification of any natural part of the female reproductive system." Islamic authorities in the nation also stressed that Islam opposes female genital mutilation. The Grand Mufti of Egypt, Ali Gomaa, said that it is "Prohibited, prohibited, prohibited." Egypt passed a law banning FGM. The June 2007 Ministry ban eliminated a loophole that allowed girls to undergo the procedure for health reasons. Between 2011 and 2013, statements made by the then-ruling Muslim Brotherhood made statements defending FGM as a facet of Sharia (and, according the Muslim Brotherhood and supporting clerics, therefore religiously mandated). Following the 2013 coup d'état, the Egyptian government's position returned to opposing FGM.

There had previously been provisions under the Penal Code involving "wounding" and "intentional infliction of harm leading to death," as well as a ministerial decree prohibiting FGM. In December 1997, the Court of Cassation (Egypt's highest appeals court) upheld a government banning of the practice providing that those who did not comply would be subjected to criminal and administrative punishments. In Egypt's first trial for committing female genital mutilation, two men were acquitted in November 2014; the doctor was ordered to pay the girl's mother compensation. In 2015 after an appeal the doctor was sentenced to more than two years in prison and the father was given a three-month suspended sentence. On 30 May 2018, the Dar al-Ifta al-Misriyyah, a governmental body which advises on Islamic law, declared FGM "religiously forbidden." Health Minister Ahmed Emad el-Din Rady presented a six-step plan to eliminate FGM in Egypt by 2030.

Eritrea

The government of Eritrea surveyed and published an official FGM prevalence rate of 89% in 2003. It was once over 93%. Historically, about 50% of the women in rural areas underwent Type III with stitching to close the vulva, while Type I and II was more common in urban areas. Overall, about a third of all women in Eritrea have undergone Type III FGM with stitching. Most FGM (68%) are performed on baby girls less than 1 year old, another 20% before they turn 5 years old. About 60% and 18% of Eritrean women believe FGM is a religious requirement, according to UNICEF, and the Eritrean government, respectively.

The prevalence varies with woman's religion, as well as by their ethnic group. A 2002 UNICEF study shows FGM prevalence among 99% of Muslim, 89% of Catholic and 85% of Protestant women aged 15–49 years. Eritrea outlawed all forms of female genital mutilation with Proclamation 158/2007 in March 2007. The law envisions a fine and imprisonment for anyone conducting or commissioning FGM.

Ethiopia

The WHO gives a prevalence of 65% for FGM in Ethiopia (2016) in women age 15–49 and falling to 47.1 in those 15–19 years. In a 2016 UNICEF report, Ethiopia's regional prevalence of FGM is : Afar Region – 91.2%; Somali Region – 98.5%; Harari Region – 81.7%; Dire Dawa 75.3%; Amhara Region – 1.4% to 21.9%; Oromia Region – 75.6%; Addis Ababa City – 54%; Benishangul-Gumuz Region – 62.9%; Tigray Region – 24.2%; Southern Region – 62%; Gambela Region 33%. By ethnicity, it has a prevalence of 98.5% in Somali; 92.3% Hadiya; 98.4% Afar and 23% Tigray. The prevalence also varies with religion in Ethiopia; FGM is prevalent in 92% of Muslim women and with lower prevalence in other religions: 65.8% Protestants, 58.2% Catholics and 55% Traditional Religions. FGM has been made illegal by the 2004 Penal Code.

Gambia

Main article: Female genital mutilation in the Gambia

Female genital mutilation is prevalent in The Gambia. A 2006 UNICEF survey found a 78.3% prevalence rate in The Gambia. In a 2013 report, an estimated 76.3% of girls and women have been subjected to FGM/C. As FGM is less prevalent among younger women according to City University London in 2015, this suggested a decline in the practice.

The Gambia's predominant religion is Islam (90%), and it has many ethnic groups. Prevalence rates of FGM/C vary significantly between the ethnic groups: Sarahule (FGM rate of 98%), Mandinka (97%), Djola (87%), Serer (43%), and Wolof (12%). Urban areas report FGM/C rates of about 56%, whereas in rural areas, rates exceed 90%. A majority of Gambian women who underwent FGM/C claimed they did it primarily because religion mandates it. The age when FGM is done on Gambian girls ranges from 7 days after birth up to pre-adolescence.

A 2011 clinical study reports 66% FGMs in The Gambia were Type I, 26% were Type II and 8% Type III. About a third of all women in Gambia with FGM/C, including Type I, suffered health complications because of the procedure. In 2015, Gambia's president Yahya Jammeh has banned FGM. This was however attempted to be repealed by a local parliamentarian in 2024, which was met with stiff resistance from public health scholars like Cham Kebba Omar through his work in Edward & Cynthia Institute of Public Health and Fatou Boye in her column in CHD Group.

Ghana

Female genital mutilation is present in Ghana in some regions of the country, primarily in the north of the country, in Upper East Region. According to the WHO, its prevalence is 3.8%. In 1989, the head of the government of Ghana, President Rawlings, issued a formal declaration against FGM. Article 39 of Ghana's Constitution also provides in part that traditional practices that are injurious to a person's health and well being are abolished. The Criminal Code was amended in 1994 to outlaw FGM, and the law was strengthened in 2007. Ghana ratified the Maputo Protocol in 2007.

Guinea

Guinea has the second highest FGM prevalence rate in the world. In a 2005 survey, 96% of all Guinea women aged between 15 and 49 had been cut. That is a slight decline in the practice from the 1999 recorded FGM rate of 98.6%. Among the 15- to 19-year-olds the prevalence was 89%, among 20- to 24-year-olds 95%. About 50% of the women in Guinea believe FGM is a religious requirement. Guinea is predominantly a Muslim country, with 90% of the population practicing Islam. The high FGM rates are observed across all religions in Guinea; FGM is prevalent in 99% of Muslim women, 94% of Catholics and Protestants, and 93% of Animist women.

FGM is illegal in Guinea under Article 265 of the Penal Code. The law sentences death to the perpetrator if the girl dies within 40 days after the FGM. Article 6 of the Guinean Constitution, which outlaws cruel and inhumane treatment, could be interpreted to include these practices, should a case be brought to the Supreme Court. Guinea signed the Maputo Protocol in 2003 but has not ratified it.

Article 305 of Guinea's penal code also bans FGM, but nobody has yet been sentenced under any of Guinea's FGM-related laws. In Guinea, instead of stopping FGM, the trend is towards medicalization of FGM, where the mutilation is advertised under hygienic conditions by medically trained staff, who see FGM practice an additional source of income. Per the above 2005 survey, 27% of girls were cut by medically trained staff.

Guinea-Bissau

Female genital mutilation is present in Guinea-Bissau, and have been estimated at a 50% prevalence rate in 2000. A law banning the practice nationwide was adopted by Parliament in June 2011 with 64 votes to 1. At the time, 45% of women aged 15 to 49 years were affected by FGM. According to a survey, 33% of women favoured a continuation of genital cutting, but 50% of the overall population wanted to abandon the practice.

Kenya

Female genital mutilation is present in Kenya. The 2014 Kenya Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) estimated the national prevalence of FGM to be 21% among women age 15–49, down from 27% in the 2008/09 survey and 32 percent in the 2003 survey. The prevalence of FGM in 2014 varied widely by age, location, ethnic group, and religion. Prevalence of FGM increases with age. It is lowest among women ages 15–19 at 11.4%, and highest among women aged 45–49 at 40.9%. This trend underscores the declining trend in FGM over time. In March 2020, the percentage of women and girls aged 15 to 49 living in Kenya who had undergone FGM was reportedly still 21%.

By region, prevalence in 2014 was highest in the former provinces of North Eastern (97.5%), Nyanza (32.4%), Rift Valley (26.9%), and Eastern (26.4%), and lower in Central (16.5%), Coast (10.2%), Nairobi (8.0%), and Western (0.8%). It is more common in rural areas (25.9%) than urban (13.8%). By ethnic group, FGM is most prevalent among women in the Somali (93.6%), Samburu (86.0%), Kisii (84.4%), and Maasai (77.9%) ethnic groups. By religion, it is more prevalent in Muslim women (51.1%) and women listing no religion (32.9%) and less prevalent in Roman Catholic (21.5%) and Protestant or other Christian women (17.9%).

In 2001 Kenya enacted the Children's Act, under the provisions of which FGM was criminalized when practiced on girls younger than 18. The practice was made illegal nationwide in September 2011.

Liberia

Female genital mutilation is prevalent in Liberia. Genital mutilation is a taboo subject in Liberia. It is difficult to get accurate data on FGM prevalence rate. The FGM procedure is mandatory for initiation of women into the secret Liberia and Sierra Leone society called the Sande society, sometimes called Bondo. A 2007 demographic survey asked women if they belonged to Sande society. It was assumed that those who were part of Sande society had undergone FGM. Based on this estimation method, the prevalence of FGM in Liberia has been estimated as 58%. Liberia has consented to international charters such as CEDAW as well as Africa's Maputo Protocol. National legislation explicitly making FGM punishable by law has yet to be passed. As FGM was less prevalent among younger women in a 2015 study, this suggested a decline in the practice.

Libya

Female genital mutilation is discouraged in Libya and as of 2007 had been practiced only in remote areas by migrants from other African countries.

Malawi

Female genital mutilation is practiced in Malawi mostly in the following districts. Southern Malawi: Mulanje, Thyolo, Mangochi and parts of Machinga and Chiradzuro District. In the Northern part of Malawi: Nkhatabay. This custom is common among the Tonga tribe, Yao tribe and Lomwe tribe. It is a custom which has been there for generations. In some villages it is deeply rooted compared to others. Every FGM camp has its own degree of how deep they want to conduct the custom but the motive is the same. It is shrouded in silence. Not even the government authorities can trace the roots because the high powers are given to the local authorities of the village and clan.

Mali

Female genital mutilation is prevalent in Mali. The WHO gives a prevalence of 85.2% for women aged 15–49 in 2006 in Mali. In a 2007 report, 92% of all Mali women between the ages of 15 and 49 had been subjected to FGM. The rates of FGM are lower only among the Sonrai (28%), the Tamachek (32%) and the Bozo people (76%). Nearly half are Type I, another half Type II. The prevalence varies with religion in Mali; FGM is prevalent in 92% of Muslim women, 76% of Christians.

About 64% of the women of Mali believe FGM is a religious requirement. In 2002, Mali created a government program aimed at discouraging FGM (Ordinance No. 02-053 portant creation du programme national de lutte contre la pratique de l’excision ). There is no specific legislation criminalizing FGM.

Mauritania

Female genital mutilation is prevalent in Mauritania. According to 2001 survey, 71% of all women aged between 15 and 49 had undergone FGM. A 2007 demographic cluster study found no change in FGM prevalence rate in Mauritania. Type II FGM is most frequent. About 57% of Mauritania women believe FGM is a religious requirement. Mauritania is 99% Muslim. The FGM prevalence rate varies by ethnic groups: 92% of Soninke women are cut, about 70% of Fulbe and Moorish women, but only 28% of Wolof women have undergone FGM. Mauritania has consented to international charters such as CEDAW as well as Africa's Maputo Protocol. Ordonnance n°2005-015 on child protection restricts FGM.

Niger

Female genital mutilation is present in Niger. In a 2006 survey, about 2% of Niger women had undergone FGM. In 1998, Niger reported a 4.5% prevalence rate. This survey data is potentially incorrect because, adjusted for age group, the women who claimed to have experienced FGM at the previous survey still are, albeit in a different age group. The 2006 survey implies more women had never experienced FGM than previously reported. The DHS surveyors claim the adoption of criminal legislation and fear of prosecution may explain why Niger women did not want to report having been circumcised. A WHO report estimates the prevalence rate of FGM in Niger to be 20%. Other sources, including a UNICEF 2009 report, claim FGM rates are high in Niger. A law banning FGM was passed in 2003 by the Niger government.

Nigeria

Main article: Female genital mutilation in NigeriaA 2008 demographic survey found 30% of all Nigerian women have been subjected to FGM. This contrasts with 25% reported by a 1999 survey, and 19% by 2003 survey. This suggests no trend, unreliable past or most recent survey data in some regions, as well as the possibility that a number of women are increasingly willing to acknowledge having undergone FGM. Another possible explanation for higher 2008 prevalence rate is the definition of FGM used, which included Type IV FGMs. In some parts of Nigeria, the vagina walls are cut in new born girls or other traditional practices performed – such as the angurya and gishiri cuts – which fall under Type IV FGM classification of the World Health Organization. Over 80% of all FGMs are performed on girls under one year of age. The prevalence varies with religion in Nigeria; FGM is prevalent in 31% of Catholics, 27% of Protestant and 7% of Muslim women. FGM was banned throughout the country in 2015.

Republic of the Congo

FGM is not commonly practiced in the Republic of the Congo, but some sources estimate its prevalence at 5%.

Rwanda

Female genital mutilation is not practiced in Rwanda.

Senegal

Female genital mutilation is present in Senegal. According to 2005 survey, FGM prevalence rate is 28% of all women aged between 15 and 49. There are significant differences in regional prevalence. FGM is most widespread in the Southern Senegal (94% in Kolda Region) and in Northeastern Senegal (93% in Matam Region). FGM rates are lower in other regions: Tambacounda (86%), Ziguinchor (69%), and less than 5% in Diourbel and Louga Regions. Senegal is 94% Muslim. The FGM prevalence rate varies by religion: 29% of Muslim women have undergone FGM, 16% of Animists, and 11% of Christian women.

A law that was passed in January 1999 makes FGM illegal in Senegal. President Diouf had appealed for an end to this practice and for legislation outlawing it. The law modifies the Penal Code to make this practice a criminal act, punishable by a sentence of one to five years in prison. A spokesperson for the human rights group RADDHO (The African Assembly for the Defense of Human Rights) noted in the local press that "Adopting the law is not the end, as it will still need to be effectively enforced for women to benefit from it. Senegal ratified the Maputo Protocol in 2005.

Sierra Leone

Female genital mutilation is prevalent in Sierra Leone. According to a 2008 survey, 91% of women in Sierra Leone between the ages of 15 and 49 have undergone FGM. The highest rate of prevalence is in the Northern Sierra Leone (97%). Type II is most common, but Type I is known as well as Type III. In a 2013 report, researchers first conducted verbal surveys followed by clinical examination. They found that the verbal disclosure were not completely reliable, and clinical examination showed greater extent of FGM. These researchers report 68% Type II and 32% Type I in Sierra Leone women.

Like Liberia, Sierra Leone has the traditional secret society of women, called Bondo or Sande society, which uses FGM as part of the initiation rite. 70% of the population is Muslim, 20% Christian, and 10% as traditional religions. The predominantly Christian Creole people are the only ethnicity in Sierra Leone not known to practice FGM. There is no federal law against FGM in Sierra Leone; and the Soweis – those who do FGM excision – wield considerable political power during elections.

Somalia

FGM is almost universal in Somalia, and many women undergo infibulation, the most extreme form of female genital mutilation. According to a 2005 WHO estimate, about 97.9% of Somalia's women and girls underwent FGM. This was at the time the world's highest prevalence rate of the procedure. A 2010 UNICEF report also noted that Somalia had the world's highest rate of Type III FGM, with 79% of all Somali women having undergone the procedure; another 15% underwent Type II FGM. Article 15 of the Federal Constitution adopted in August 2012 prohibits female circumcision, stating: "Circumcision of girls is a cruel and degrading practice, and is tantamount to torture. The circumcision of girls is prohibited". However, as of March 2020 there are no laws and no known prosecutions of FGM in Somalia.

Somaliland and Puntland

The prevalence rate varies considerably by region and is reportedly on the decline in the northern part of the country. Somaliland in the northwest is a self-proclaimed independent state and de facto functioning as such since 1991, but internationally recognised as part of Somalia, while Puntland in the northeast has self-proclaimed autonomy within Somalia since 1998.

According to the UNICEF Somaliland Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey report (final version published in 2014), the prevalence of FGM in Somaliland in 2011 was 99.1% amongst women aged 15–49. Most of these women had been cut as girls between the ages of 4 and 14, with 85% of them having undergone Type III. However, 69% of women aged 15–49 who had heard of FGM believed it should be discontinued, while 29% wanted it to continue. Only 27.7% of Somaliland girls aged 4–14 were reportedly cut in 2011, indicating a strong decline in the practice. Younger women were also more likely to oppose FGM than older women. In an announcement on the preliminary report in April 2013, UNICEF in conjunction with the Somali authorities stated that the FGM prevalence rate among 1- to 14-year-old girls in the autonomous northern Puntland and Somaliland regions had dropped to 25% following a social and religious awareness campaign. A bill criminalising FGM was proposed in the Somaliland parliament in 2018; as of August 2019, it has not passed yet. Also in 2018, religious authorities issued a fatwa to condemn the two most severe forms of FGM, but it allowed mixed interpretations on lesser forms of FGM. With only limited government support, health workers from the Somaliland Family Health Association (SOFHA) were campaigning to end the practice by educating citizens village by village. In January 2020, the Somaliland Ministry of Religious Affairs announced the formation of a committee consisting of nine clerics to " with the issue of female genital mutilation, which needs to be in line with Islamic law", while stating that the ministry is "committed to combating female genital mutilation". British-Somali anti-FGM campaigner Nimco Ali reacted by saying that especially "religious leaders in the Ministry of Religion and Welfare, who may not agree to an outright ban on all types of FGM", were complicating eradication efforts.

South Africa

While South Africa is not listed among the countries with a high prevalence of FGM, the practice is present among certain communities in South Africa. FGM is practiced among the Venda community in north-east South Africa, at about eight weeks or less after childbirth. It is also present among immigrant communities.

South Sudan

Female genital mutilation is present in South Sudan, but its exact prevalence is unknown. A 2015 UNICEF report claimed 1% of women aged 15–49 had been subjected to FGM, but as of May 2018 there were no recent data confirming this figure. FGM has been reported to be practiced in some Christian and Muslims communities, and has been noted in some refugee camps in Upper Nile State. South Sudanese law has banned female genital mutilation, but the government has not enacted a clear plan to eradicate the phenomenon.

Sudan

The prevalence of FGM in Sudan is 90%. Until 2020, only six of the eighteen states of Sudan had laws against FGM. In 2020, the new government of Sudan of Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok passed a law to outlaw FGM.

Before the Sudanese Revolution, the 32nd Article of the Constitution of Sudan promised that the "state shall combat harmful customs and traditions which undermine the dignity and the status of women." Sudan was the first country to outlaw it in 1946, under the British. Type III was prohibited under the 1925 Penal Code, with less severe forms allowed. Outreach groups have been trying to eradicate the practice for 50 years, working with NGOs, religious groups, the government, the media and medical practitioners. Arrests have been made but no further action seems to have taken place. Sudan signed the Maputo Protocol in June, 2008 but no ratification has yet been deposited with the African Union.

Tanzania

According to 2015–16 survey in Tanzania, FGM prevalence rate is 10% of all women aged between 15 and 49 and 4.7% for those aged 15–19. In contrast, the 1996 survey reported 17.6, suggesting a drop of 7.6% over 20 years or unwillingness to disclose. Type II FGM was found to be most common. There are significant differences in regional prevalence; FGM is most widespread in Manyara (81%), Dodoma (68%), Arusha (55%), Singida (43%) and Mara (38%) regions. The practice varies with religion, with reported prevalence rates of 20% for Christian and 15% of Muslim women.

Section 169A of the Sexual Offences Special Provisions Act of 1998 prohibits FGM in Tanzania. Punishment is imprisonment of from five to fifteen years or a fine not exceeding 300,000 shillings (approximately US$250) or both. Tanzania ratified the Maputo Protocol in 2007. As with Kenya, Tanzania 1998 Act protects only girls up to the age of 18 years. The FGM law is being occasionally implemented, with 52 violations have been reported, filed and prosecuted. At least 10 cases were convicted in Tanzania.

Togo

Female genital mutilation is practiced in Togo. In a 2014 UNICEF report, the prevalence is 1.8% in girls 15–19. The WHO puts its prevalence at 5.8% in 2006. Other sources cite 12% and 50% as prevalence. Type II is usually practiced. On October 30, 1998, the National Assembly unanimously voted to outlaw the practice of FGM. Penalties under the law can include a prison term of two months to ten years and a fine of 100,000 francs to one million francs (approximately US$160 to 1,600). A person who had knowledge that the procedure was going to take place and failed to inform public authorities can be punished with one month to one year imprisonment or a fine of from 20,000 to 500,000 francs (approximately US$32 to 800). Togo ratified the Maputo Protocol in 2005.

Uganda

Anyone convicted of carrying out FGM is subject to 10 years in prison. If the life of the patient is lost during the operation a life sentence is recommended. In 1996, a court intervened to prevent the performance of FGM under Section 8 of the Children Statute, which makes it unlawful to subject a child to social or customary practices harmful to the child's health. Uganda signed the Maputo Protocol in 2003 but has not ratified it. In early July 2009, President Yoweri Museveni stated that a law would soon be passed prohibiting the practice, with alternative livelihoods found for its practitioners. The anti FGM act 2010 is currently available for reference. The speaker of Parliament Ms Rebecca Kadaga recently gave Sebei sub-region districts ultimatum to produce working plans to end Female Genital Mutilation in the area.

Asia

Anti-FGM organizations in Asia have complained that global attention on eradicating FGM goes almost entirely to Africa. Consequently, few studies have been done into FGM in Asian countries, complicating anti-FGM campaigns due to a lack of data on the phenomenon. Indian activist Masooma Ranalvi, who underwent FGM as a 7-year-old, was quoted as saying: "The entire discourse on FGM up to now has centred on Africa. Africa of course needs attention but maybe there are other places where the focus can be spread to."

Bahrain

Female genital mutilation is present in Bahrain. There are currently no laws that expressly prohibit female genital mutilation and no data is available regarding the prevalence of the issue. However, there are recorded cases of various victims being at high risk of getting mutilated.

Brunei

According to reports, Type I and Type IV FGC, including symbolic FGC and clitoral hood removal, are most likely practised in Brunei. According to Brunei's Ministry of Religious Affairs, female circumcision—which involves the removal of the clitoral hood—is a "sunat," or required religious rite for Muslim women. There are no laws against FGM, and there have been no major studies, but one researcher found it is performed on babies shortly after birth, aged 40 to 60 days.

India

Main article: Female genital mutilation in IndiaThe practice of FGM constitutes a criminal offense under the Protection of Children from Sexual Offences Act, 2012; Indian Penal Code, 1860 and Criminal Procedure Code, 1973. It is practiced primarily in the Ismaili Shia Muslim Bohra community with estimates suggesting 90% of them undergo FGM. There are about 2 million Bohras in India. In a survey, over 70% Bohra respondents said an untrained professional had performed the procedure on them. Female genital cutting is being practiced in Kerala was found in August 2017 by Sahiyo reporters. Apart from the mental trauma, the women also said it also led to physical complications.

On May 9, 2017, the Supreme Court of India sought a response from the centre and four states (Maharashtra, Delhi, Gujarat and Rajasthan) on the validity of Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) when Public Interest Litigation by some Bohra women to ban the practice. On July 9, 2018, Attorney General of India K. K. Venugopal reiterated the Indian government's position that FGM was a violation of a person's fundamental rights and that its practice resulted in serious health complications for the girl concerned.

Indonesia

Female genital mutilation Type I and IV is prevalent in Indonesia; 49% of girls are mutilated by age 14, and 97.5% of the surveyed females from Muslim families (Muslim females are at least 85% of females in Indonesia) are mutilated by age 18 (55 million females as of 2018). In certain communities of Indonesia, mass female circumcision (khitanan massal) ceremony are organized by local Islamic foundations around Prophet Muhammad's birthday. Some FGM are Type IV done with a pen knife, others are Type I done with scissors. Two Indonesian nationwide studies in 2003 and 2010 found over 80% of the cases sampled involved cutting, typically of newborns through the age of 9. Across the sites, among all the children aged 15–18, 86–100% of the girls were reported already circumcised.

Historical records suggest female circumcision in Indonesia started and became prevalent with the arrival of Islam in the 13th century as part of its drive to convert people to Islam. In islands of Indonesia, where partial populations converted to Islam in the 17th century, FGM has been prevalent in Muslim females only. In 2006, FGM was banned by the government but FGM/C remained commonplace for women in Indonesia, which houses the world's largest Muslim population. In 2010, the Indonesian Health Ministry issued a decree outlining the proper procedure for FGM, which activists claim contradicted the 2006 ruling prohibiting clinics from performing any FGM.

In 2013, the Indonesian Ulema Council ruled that it favors FGM, stating that although it is not mandatory, it is still “morally recommended”. The Ulema has been pushing Indonesian government to mutilate girls, claiming it is "part of Islamic teachings". Some Indonesian officials, in March 2013, claimed cutting and pricking type circumcision is not FGM. In 2014 the government criminalized all forms of FGM after it repealed exceptions to the laws.

According to 2016 report by UNICEF, 49% of Indonesian girls of age below 14 had already undergone FGM/C by 2015.

The Government Regulation Number 28 of 2024 regulates the abolition of female genital mutilation (FGM) practice in Indonesia. The Government Regulation regulates that "Efforts for the reproductive system health of infants, toddlers and preschool children as referred to in Article 101 paragraph (1) letter A are at least in the form of: A. abolish the practice of female circumcision.”

Iran

FGM is criminalized by the Islamic Penal Code of 2013. Article 663 explicitly mentions the following: "Mutilating or injuring either side of a woman's genitals shall carry the Diya penalty equal to half of the full Diya. Mutilating or injuring parts of the genitals shall have a proportionate penalty based on the level of injury." Article 269 of the Islamic Penal Code of 1991 criminalizes "intentional mutilation or amputation" without explicitly mentioning FGM.

National data on FGM in Iran are unknown. Various studies have been conducted on prevalence in provinces and counties, suggesting significant regional differences. FGM is known to be prevalent in four provinces: West Azerbaijan Province (mostly the Kurdish populated southern part), Kurdistan Province and Kermanshah Province in the Kurdish-dominated northwest, and Hormozgan Province and islands near it in the south.

FGM in Iran is primarily associated with Sunni Muslims following the Shafi‘i madhhab, especially those living in certain Sorani Kurdish-populated, and to a lesser extent Azerbaijani-populated, rural areas in northwestern Iran, adjacent to the Sorani Kurdish-speaking regions in northeastern Iraq where FGM also has a relatively high presence compared to the non-Kurdish areas around it. There is strong disparity even within the Kurdish communities, and the prevalence may differ considerably from one village to the next. Unlike the Iraqi Kurdistan government, which has implemented a relatively successful anti-FGM campaign, official representatives as well as nationalist individuals or groups tend to deny FGM even exists in Iran. In the southern province of Hormozgan, FGM is mostly practiced by Sunnis, but also a small minority of Shias near them.

The issue is rarely discussed in public; the national Shia religious establishment claims it as an exclusively Sunni practice in which it should not get involved, and generally sees no reason to try to end it. It is also rarely the subject of research in academia, with the government neither permitting nor funding any public engagement projects for the affected regions.

In 2016, Susie Latham reported that FGC had been abandoned around the capital of the south-western province Khuzestan in the 1950s. Research by Kameel Ahmady (2005–2015) also revealed the practice had been abandoned in several other parts of Iran, such as among Shia Kurdish women in parts of Kermanshah and Ilam Province.

Some studies estimate the Type I and II FGM among Iraqi migrants and other Kurdish minority groups to be variable, ranging from 40% to 85%.

| Province | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hormozgan Province | – | – | 68% | 66% | 62% | 60% |

| Kermanshah Province | – | 31% | 28% | 25% | 20% | 18% |

| Kurdistan Province | – | 29% | 28% | 23% | 20% | 16% |

| West Azerbaijan Province | 39% | 36% | 32% | 32% | 25% | 21% |

Assuming FGM had no significant presence in other provinces, this would amount to a national prevalence of c. 2% in Iran in 2014.

| County | Prevalence | Notes | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ravansar County | 55.7% | Tahereh Pashaei et al. | |

| Minab County | 70% | Khadivzadeh et al. | |

| Qeshm County | 7.2% (Shia Muslims) 70% (Sunni Muslims) |

FGM in decline |

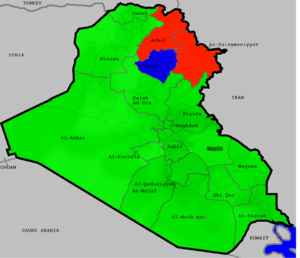

Iraq

Female genital mutilation is prevalent in Iraqi Kurdistan, with an FGM rate of 72% according to the 2010 WADI report for the entire region and exceeding 80% in Garmyan and New Kirkuk. In Erbil Governorate and Suleymaniya, Type I FGM is common; while in Garmyan and New Kirkuk, Type II and III FGM are common. There was no law against FGM in Iraqi Kurdistan, but in 2007 a draft legislation condemning the practice was submitted to the Regional Parliament, but was not passed. A 2011 Kurdish law criminalized FGM practice in Iraqi Kurdistan and this law is not being enforced.

A field report by Iraqi group PANA Center, published in 2012, shows 38% of females in Kirkuk and its surrounding districts areas had undergone female circumcision. Of those females circumcised, 65% were Kurds, 26% Arabs and rest Turkmen. On the level of religious and sectarian affiliation, 41% were Sunnis, 23% Shiites, rest Kaka’is, and none Christians or Chaldeans. A 2013 report finds FGM prevalence rate of 59% based on clinical examination of about 2000 Iraqi Kurdish women; FGM found were Type I, and 60% of the mutilation were performed to girls in 4–7 year age group. See Asuda, a Kurdistan NGO. The highest prevalence rates of FGM are in Kirkuk (20%), Sulaymaniyah (54%) and Erbil (58%).

Israel

Though illegal, female circumcision is still practiced among the Negev Bedouin, and tribal secrecy among the Bedouin makes it difficult for authorities to enforce the ban. However, multiple other reports state that it has been completely eradicated by Israeli Government.

Jordan

Residents of Wadi Araba village in southern Jordan are known to practice FGM. The practice is foreign to the rest of the country, experts speculate that this practice was introduced through descendants of tribes that came from neighbouring Gaza and Beer Sheba.

Malaysia

Female genital mutilation Type I is prevalent in Malaysia, where 93% of females from Muslim families (about 9 million females) have been mutilated. It is widely considered as a female sunnah tradition (sunat perempuan), typically in the old days done by midwife (mak bidan) and now by medical physician. It is either a minor prick or cutting off a small piece of the highest part of clitoral hood and foreskin (Type I). Malaysian women claim religious obligation (82%) as the primary reason for female circumcision, with hygiene (41%) and cultural practice (32%) as other major motivators for FGM prevalence.

Malaysia is a multicultural society. FGM is only prevalent in the Muslim community, and not among minority Buddhist and Hindu communities. Malaysia has no laws in reference to FGM. The Malaysian government sponsored 86th conference of Malaysia's Fatwa Committee National Council of Islamic Religious Affairs held in April 2009 decided that female circumcision is part of Islamic teachings and it should be observed by Muslims, with the majority of the jurists in the Committee concluding that female circumcision is obligatory (wajib). The fatwa noted harmful circumcision methods are to be avoided. In 2012, Malaysian government health ministry proposed guidelines to reclassify and allow female circumcision as a medical practice.

Maldives

Female genital mutilation is practiced in Maldives. Maldives' Attorney General Husnu Suood claims FGM was eradicated from Maldives by the 1990s, but the practice of female circumcision in Maldives is reviving because of Islamic fatwas from religious scholars in Maldives who preach that it as compulsory. Religious leaders have renewed their calls for FGM in 2014.

Oman

The practice is very prevalent in Oman. A 2013 article by journalist Susan Mubarak describes FGM practice in Oman, and claims the practice is very common in Dhofar in the southwest. The author went on to say that a previous article on the topic received both positive feedback for spreading awareness of what some considered a "horrific tradition", as well as negative feedback from others for "hanging Dhofar's dirty washing for the world to see and criticising a practice that they believe is purely Islamic", commenting that she "paid little attention to these criticisms because I know the practice is harmful and primitive", and "our religion neither encourages the practice nor condemns it."

According to a small survey by human rights activist and statistician Habiba Al Hinai conducted in October 2013 and published in January 2014, 78% of 100 women interviewed living in the capital city of Muscat had undergone FGM. These women came from all parts of the country, each region showing a very high prevalence, and even though fewer women from Muscat itself had undergone FGM, they were still in the majority. Her findings contradicted the common belief that FGM was only widespread in the south. Type I is mostly performed in southern Oman and typically performed within a few weeks of a girl's birth, while Type IV is observed in other parts of northern Oman.

FGM otherwise is not practice in Oman neither is considered prominent by the World Health Organization.

Pakistan

Female genital mutilation is uncommon in Pakistan, as most Pakistanis follow the Hanafi and Jafari schools of thought, which do not support FGM, according to sources dated to the 1990s and 2000s. However, FGM is widespread among minorities such as the Bohra Muslims of Pakistan and the Sheedi Muslim community of Pakistan, which is considered to be of Arab-African origins. The practice is also found in Muslim communities near Pakistan's Iran-Balochistan border.

Palestine

| This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (November 2014) |

Female genital mutilation is practiced in Palestine according to an UNFPA FAQ. However another UNFPA report says that FGM/C is not practised in Palestine.

Philippines

Female genital mutilation is prevalent in parts of the Philippines. The communities that practice FGM call it Pag-Sunnat, sometimes Pag-Islam, and include Tausugs of Mindanao, Yakan of Basilan and other Muslim communities of Philippines. FGM is typically performed on girls between a few days old and age 8. Type IV FGM with complications has been reported.

Qatar

| This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (November 2014) |

Female genital mutilation is present in Qatar.

Saudi Arabia

Female genital mutilation is present in Saudi Arabia. FGM is most prevalent in Saudi regions following Shafi'i school within the Sunni sect of Islam, such as Hejaz, Tihamah and Asir. In a clinical study published in 2008, Alsibiani and Rouzi provide evidence of the practice in Saudi Arabia. A 2010 study conducted at a Jeddah hospital into the incidence of clitoral cysts found that a minimum of 46.9% (and a possible maximum of 90.7%) of cases had undergone FGM. A 2012 study reports, that of the Saudi women who had FGM, Type III was more common than Type I or II.

A 2018 survey of 365 households conducted in Hali, Al-Qunfudhah governorate, western Saudi Arabia found a prevalence of FGM of 80.3%, 59.4% of which had undergone FGM at the age 7 years or younger, and almost always by a doctor (91.4%).

A 2019 survey of women attending obstetrics and gynaecology clinics at King Abdulaziz University Hospital, Jeddah, found that of the 963 women surveyed, 175 (18.2%) had undergone FGM.

Singapore

Female genital mutilation is practiced by the Malay Muslim community in Singapore. Malay Muslims typically carry out the practice on girls before the age of two. Many Malay Muslims, especially the older generations, believe FGM reduces women's libido and decreases the risk of sex outside marriage.

Sri Lanka

Female genital mutilation is practiced by the Muslim minority in Sri Lanka.

Syria

Circumstantial evidence suggests FGM exists in Syria. A 2012 conference confirmed that FGM is observed in Syria.

Thailand

Female genital mutilation is practiced by the Muslim population in the south of Thailand.

Turkey

Though there is little hard evidence of the practice of FGM in Turkey, circumstantial evidence suggests FGM exists in the southern Turkey where the majority of the population is Kurdish.

United Arab Emirates

The WHO mentions a study that documents FGM in the United Arab Emirates, but does not provide data. The practice has been banned in Government hospitals and clinics, but is reportedly still prevalent in rural and urban UAE. In a 2011 survey, 34% of Emirati female respondents said FGM had been performed on them, and explained the practice to customs and tradition. FGM is a controversial topic in UAE, and people argue about whether it is an Islamic requirement or a tribal tradition. A significant number of UAE nationals follow in the footsteps of their parents and grandparents without questioning the practice.

Yemen

According to a 2008 UNICEF report, 30% prevalence; in addition to the adult prevalence, UNICEF reports that 20% of women aged 15–49 have a daughter who had the procedure in Yemen. In 4 of Yemen's 21 governorates, according to a 2008 report, the FGM prevalence rates exceed 80%: al-Hudaydah (97%), Hadhramaut (97%), al-Mahrah (97%) and Adan (82%); Sana'a Governorate, which includes the capital of Yemen, has a prevalence rate of 46%. Type II FGM was most common, accounting for 83% of all FGMs. Type I FGMs accounted for 13%.

Yemeni tradition is to carry out the FGM on a newborn, with 97% of FGM being done within the first month of a baby girl. In 2001, Yemen banned FGM in all private and public medical facilities by a government decree, but not homes. The Yemeni government did not enforce this decree. In 2009, conservative Yemeni parliamentarians opposed the adoption of a nationwide criminal law against FGM. In 2010, the Ministry of Human Rights of Yemen launched a new study to ascertain over 4 years if FGM is being practiced in Yemen, then propose a new law against FGM. A 2013 UNICEF report claims Yemen's FGM prevalence rate have not changed in last 30 years.

Europe

Overview

The Council of Europe Convention on preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence (also known as the Istanbul Convention), which came into force on 1 August 2014, defines and criminalises the practice in Article 38:

Article 38 – Female genital mutilation

Parties shall take the necessary legislative or other measures to ensure that the following intentional conducts are criminalised:

- excising, infibulating or performing any other mutilation to the whole or any part of a woman’s labia majora, labia minora or clitoris;

- coercing or procuring a woman to undergo any of the acts listed in point a;

- inciting, coercing or procuring a girl to undergo any of the acts listed in point a.

- Pre-migratory FGM

In the early 21st century, the increase in immigration for individuals from countries where FGM is commonly practiced has made FGM a noticeable phenomenon in European societies that has raised concerns. FGM prevalence rates have been difficult to quantify among immigrants to European countries. A 2005 case study which investigated FGM in groups of migrant women from Northern Africa to European regions like Scandinavia, noted that a majority of these women had FGM before their migration to Europe. A 2016 epidemiological study by Van Baelen et al. estimated that, based on 2011 census data, more than 500,000 girls and women living in the European Union, Norway and Switzerland had undergone FGM before migrating to those European countries. Half of these girls and women were living in the United Kingdom or France; one in two was born in East Africa.

- Post-migratory FGM

It has also been established that African communities in European countries continue the practice of FGM on their daughters after migrating to Europe. For instance in Sweden, a study by Karolinska Institutet concluded that about a third of families migrated from countries with an FGM culture wanted to continue mutilating in their new countries.

France

Between 1979 and 2004, a total of 29 FGM court cases were brought before criminal courts, mostly from the mid-1990s onwards and with aggravated sentences. By 2013, more than 100 people had been convicted of FGM. FGM is a criminal offense punishable by 10 years or up to 20 years in jail if the victim is under 15 years of age. The law requires anyone to report any case of mutilation or planned mutilation. In 2014 it was reported that about 100 people in France had been jailed. Not only the person carrying out the mutilation is sentenced, parents organising the crime face legal proceedings as well.

Germany

According to women's right organization Terre des Femmes in 2014, there were 25,000 victims in Germany and a further 2,500 were at risk of being mutilated. In 2018, the estimate had increased to 65000. A further 15500 were at risk of having the mutilation done to them which represented an increase of 17% on the previous year.

According to the BMFSFJ most of the victims originated in Eritrea, Indonesia, Somalia, Egypt and Ethiopia.

Ireland

AkiDwA, an NGO providing a network for immigrant women in Ireland, estimated in 2016 that between 3,000 and 5,000 girls and women in the country had been subjected to FGM. A 2012 act of the Oireachtas (parliament) criminalises FGM (including outside the state) and removal of a person from the state for the purposes of FGM; the maximum prison sentence for each is 14 years. The first conviction was in November 2019, for a September 2016 offence by the father and mother of a girl aged 21 months, who were sentenced to 5 years 6 months and 4 years 9 months in prison. The Health Service Executive has responsibility for raising awareness of the health and legal risks, and liaises with AkiDwA. The Irish Family Planning Association runs a clinic for FGM survivors.

On a Prime Time report on FGM broadcast on 8 February 2018, Ali Selim of the Islamic Cultural Centre of Ireland said "female circumcision" should be allowed with medical approval. Protesting students in Selim's Arabic-language class at Trinity College Dublin (TCD) were offered an alternative lecturer, while TCD Students' Union called for his part-time post to be terminated. On 12 February Umar Al-Qadri of the separate Al-Mustafa Islamic Cultural Centre Ireland issued a fatwa against FGM. On 18 February Selim apologised for not clearly distinguishing medically necessary interventions from FGM, and condemned the latter. TCD later made Selim redundant on the grounds of course reorganisation and low student demand; in September 2019 the Labour Court awarded him compensation for unfair dismissal.

Italy

After a few cases of infibulation practiced by complaisant medical practitioners within the African immigrant community came to public knowledge through media coverage, the Law n°7/2006 was passed on 1/9/2006, becoming effective on 1/28/2006, concerning "Measures of prevention and prohibition of any female genital mutilation practice"; the Act is also known as the Legge Consolo ("Consolo Act") named after its primary promoter, Senator Giuseppe Consolo. Article 6 of the law integrates the Italian Penal Code with Articles 583-Bis and 583-Ter, punishing any practice of female genital mutilation "not justifiable under therapeutical or medical needs" with imprisonment ranging from 4 to 12 years (3 to 7 years for any mutilation other than, or less severe than, clitoridectomy, excision or infibulation).

The penalty can be reduced up to 2⁄3 if the harm caused is of modest entity (i.e. if partially or completely unsuccessful), but may also be elevated up to 1⁄3 if the victim is a minor or if the offense has been committed for profit. An Italian citizen or a foreign citizen legally resident in Italy can be punished under this law even if the offense is committed abroad; the law will as well afflict any individual of any citizenship in Italy, even illegally or provisionally. The law also mandates any medical practitioner found guilty under those provisions to have his/her medical license revoked for a minimum of six up to a maximum of ten years.

Netherlands

FGM is considered mutilation and is punishable as a criminal offense under Dutch law. There is no specific law against FGM: the act is subsumed under the general offense of inflicting harm ("mishandeling" in Dutch, art. 300–304 Dutch Criminal Code). The maximum penalty is a prison sentence of 12 years. The sentence can be higher if the offender is a family member of the victim. It is also illegal to assist or encourage another person to perform FGM. A Dutch citizen or a foreign citizen legally resident in the Netherlands can be punished even if the offense is committed abroad. Doctors have the obligation to report suspected cases of FGM and may break patient confidentiality rules if necessary.

Norway

FGM is punishable as a criminal offense under Norwegian law even if the offense is committed abroad.

Russia

FGM is not a crime in Russia. A study on female genital mutilation practiced in Dagestan, made public in 2016 by Legal Initiative for Russia (also known as Russia Justice Initiative), revealed that FGM is widespread in Dagestan. The girls undergo mutilation in early age, up to three years old. The practice has been publicly approved in the predominantly Muslim region of Dagestan by religious leaders such as Mufti Ismail Berdiyev. Later an Orthodox Christian priest also backed the cleric. The Russia Justice Initiative estimated that tens of thousands of Muslim women had undergone FGM, especially in the remote mountain villages of Dagestan, but investigators from the Prosecutor General's office reported they had not found any evidence of the practice. That year, dissident United Russia MP Maria Maksakova-Igenbergs introduced a bill criminalising FGM, but its status was unclear as of 2018.

In late November 2018, Meduza exposed the Moscow-based Best Clinic as running advertisements offering 'female circumcision' to girls between the ages of 5 and 12. The clinic since removed the advertisements and stated that "clitoridectomy, a surgical procedure, is being performed only on medical grounds", denying that it was performed on female patients under the age of 18. By contrast, the Ministry of Health declined to comment on the matter, saying that female circumcision is, in fact, "not a medical procedure", and therefore "not in their competence".

Spain

The Criminal Code states that sexual mutilation, such as FGM, is a criminal offense punishable by up to 12 years in jail, even if the offence is committed abroad.

Sweden

Main article: Honor-related violence in SwedenIn 1982, Sweden was the first western country in the world to explicitly prohibit genital mutilation. It is punishable by up to six years in prison, and in 1999 the Government extended the law to include procedures performed abroad. General child protection laws could also be used. The prevalence of FGM among immigrant groups in Sweden is unknown, but there have been 46 cases of suspected genital mutilation since the law was introduced in 1982, and two convictions, according to a report published in 2011 by the National Centre for Knowledge on Men's Violence against Women.

The National Board of Health and Welfare has estimated that up to 38,000 women living in Sweden may have been the victims of FGM. This calculation is based on UNICEF estimates on prevalence rates in Africa, and refer to FGM carried out before arriving in Sweden. The Ministry of Health and Social Affairs launched an action plan against FGM in 2003, which included giving courses to African women and men, who are now working as health advisors and influencing the public opinion among their fellow countrymen. In 2014, a Somali-born national coordinator at the County Administrative Board of Östergötland said the problem is not actively being pursued by authorities and the issue is avoided for fear of being perceived as racist or as stigmatising minority ethnic groups.

United Kingdom

Main article: Female genital mutilation in the United KingdomFGM was made a criminal offence by the Prohibition of Female Circumcision Act 1985. This was superseded by the Female Genital Mutilation Act 2003, and (in Scotland) by the Prohibition of Female Genital Mutilation (Scotland) Act 2005. Taking a UK citizen or permanent resident abroad for the purpose of FGM is a criminal offence whether or not it is lawful in the country the girl is taken to. Since April 2014, all NHS hospitals will be able to record if a patient has undergone FGM or if there is a family history of this, and by September 2014, all acute hospitals will have to report this data to the Department of Health, on a monthly basis. Despite FGM being illegal since 1985 the authorities are yet to prosecute even one case successfully.

The number of women aged 15–49 resident in England and Wales born in FGM practicing regions having migrated to the UK was 182000 in 2001 and increased to 283000 in 2011. The number of women born in the Horn of Africa, where FGM is nearly universal and the most severe types of FGM, infubulation, is commonly practiced, increased from 22000 in 2001 to 56000 in 2011, an increase of 34000.

The number of women of all ages having undergone FGM rituals was estimated to be 137000 in 2011. The number of women of ages 15–49 having undergone FGM rituals was estimated to 66000 in 2001 and there was an increase to 103000 in 2011. Additionally, approximately 10,000 girls aged under 15 and 24,000 women over 50, who have migrated to England and Wales, are likely to have undergone FGM.

The city with the highest prevalence of FGM in 2015 was London, at a rate of 28.2 per 1000 women aged 15–49, by far the highest. The borough with the highest rate was Southwark, at 57.5 per 1000 women, while mainly rural areas of the UK had prevalence rate below 1 per 1000.

North America

Canada

There is some evidence to indicate that FGM is practiced in Ontario and across Canada among immigrant and refugee communities. FGM is considered child assault and prohibited under sections 267 (assault causing bodily harm) or 268 (aggravated assault, including wounding, maiming, disfiguring) of the Criminal Code.

United States

Main article: Female genital mutilation in the United StatesThe Centers for Disease Control estimated in 1997 that 168,000 girls living in the United States had undergone FGM, or were at risk. Khalid Adem, a Muslim who had moved from Ethiopia to Atlanta, Georgia, became the first person to be convicted in the US in an FGM case; he was sentenced to ten years in 2006 for having severed his two-year-old daughter's clitoris with a pair of scissors. Performing the procedure on anyone under the age of 18 became illegal in the U.S. in 1997 with the Federal Prohibition of Female Genital Mutilation Act. However, in 2018, the act was stuck down as unconstitutional by US federal district judge Bernard A. Friedman in Michigan, who argued that the federal government did not have authority to enact legislation outside the "Interstate commerce" clause. As part of the ruling, Friedman also ordered that charges be dropped against 8 people who had mutilated the genitals of 9 girls. The Department of Justice decided not to appeal the ruling; however, the US House of Representatives has appealed it. As of August 2019, 35 U.S. states have made specific laws that prohibit FGM, while the remaining 15 states had no specific laws against FGM. States that do not have such laws may use other general statutes, such as assault, battery or child abuse. The Transport for Female Genital Mutilation Act was passed in January 2013, and prohibits knowingly transporting a girl out of the U.S. for the purpose of undergoing FGM.

Fauziya Kasinga, a 19-year-old member of the Tchamba-Kunsuntu tribe of Togo, was granted asylum in 1996 after leaving an arranged marriage to escape FGM; this set a precedent in US immigration law because it was the first time FGM was accepted as a form of persecution.

In 2016, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) released a report compiled with data from 2010 to 2013. The 2013 study estimated 513,000 girls and women in the United States were either victims of FGM or at risk of FGM, with 1⁄3 under age 18. The marked increase in the number of girls and women at risk of FGM in the United States was attributed to an increase in the total number of immigrants from countries where FGM is most common, not an increase in the frequency of the practice.

Latin America

Colombia, Ecuador and Panama

The first indigenous tribe in Latin America known to practice FGM was the Emberá people, living in the Chocó Department of Colombia and across the border in the Panamanian part of the Darién Gap. Superstition held that a girl's clitoris had to be cut to prevent it from growing to become a penis. It is thought that the tradition is only a couple of centuries old, having been introduced by African slaves brought to Colombia during Spanish colonial rule. The tradition was extremely secretive and taboo until a 2007 incident, in which a girl died as a result of FGM. The incident caused much controversy, raised awareness and stimulated debate about ending the practice altogether. In 2015, it was reported that of the approximately 250,000 members of the tribe, 25,000 (10%) had decided to discontinue female genital mutilation, with a community leader saying they hoped to eradicate it by 2030. In 2017, retired prosecutor Victor Martinez claimed that FGM was also practiced amongst tribes in the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, such as the Arhuaco and Kogi people, and amongst tribes in La Guajira Department. As of March 2020, there is no law in Colombia that specifically prohibits FGM.

It has been claimed that members of the Emberá people living on the Panamanian side of the border in the Darién region also practice FGM, but the extent to which this is happening was unknown as of 2010 due to a lack of data.

It has been speculated that members of the small Emberá community living in Ecuador's northwestern Esmeraldas Province bordering Colombia might also be practicing FGM, but as of 2010 there was no evidence of that.

Peru

A 2004 anthropological study by Christine Fielder and Chris King provides a detailed account of a girl's initiation ceremony involving clitoral subincision amongst the Shipibo people, claiming the Conibo and Amahuaca tribes had a similar practice. They concluded that it was used as a means to control women's sexuality by depriving them of sexual pleasure and having an interest in taking lovers, and keeping women obedient to their husbands.

A 2010 OECD report claimed that one unnamed indigenous community appeared to "use this type of mutilation to mark girls' entry into puberty". In 2017, doctor John Chua claimed that the Shipibo people living in Peruvian Amazonia practiced FGM to make girls 'real' women, as superstition held that uncut girls could become lesbians.

Oceania

Australia

In 1994 there were several anecdotal reports of FGM being practiced amongst migrant communities in Australia. By 1997, all Australian states and territories had made FGM a criminal offence. It is also a criminal offence to take, or propose to take, a child outside Australia to have a FGM procedure performed. The incidence of FGM in Australia is unknown as it is often only uncovered when women and girls are taken to hospital due to complications with the procedure. In 2015 two unnamed women became the first people in Australia to be convicted of carrying out FGM; their case was also the first time such an offense had come to trial in Australia.

In 2017 the first national study by researches at the Westmead Children's Hospital in Sydney found 59 girls having attended medical staff since 2010, with many having had the most extreme form of the procedure done to them. A fifth of those had infibulation, the removal of the clitoris and external genitalia with the opening sewed up. The number was deemed to strongly underestimate the true number of cases. Most of the procedures had been done overseas, but two children born in Australia had the procedure done in New South Wales and a third child born in Australia had been taken to Indonesia to have the procedure done. Of the 59 girls, only 13 had been in contact with child protection services. Most (about 90%) were identified during refugee screening and had African origin. The report also stated that there was no FGM registry in Australia and even when detected is not routinely reported. The two most common countries of birth for the girls were Somalia (24) and Eritrea (12).

New Zealand

Under a 1995 amendment to the Crimes Act, it is illegal to perform "any medical or surgical procedure or mutilation of the vagina or clitoris of any person" for reasons of "culture, religion, custom or practice". It is also illegal to send or make any arrangement for a child to be sent out of New Zealand for FGM to be performed, assist or encourage any person in New Zealand to perform FGM on a New Zealand citizen or resident outside New Zealand convince or encourage any other New Zealand citizen or resident to go outside New Zealand to have FGM performed.

See also

- Asuda