| Nuclear physics |

|---|

|

| Models of the nucleus |

Nuclides' classification

|

| Nuclear stability |

| Radioactive decay |

| Nuclear fission |

| Capturing processes |

| High-energy processes |

|

Nucleosynthesis and nuclear astrophysics

|

| High-energy nuclear physics |

| Scientists |

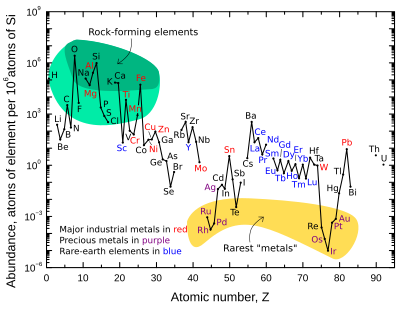

In geochemistry, geophysics and nuclear physics, primordial nuclides, also known as primordial isotopes, are nuclides found on Earth that have existed in their current form since before Earth was formed. Primordial nuclides were present in the interstellar medium from which the solar system was formed, and were formed in, or after, the Big Bang, by nucleosynthesis in stars and supernovae followed by mass ejection, by cosmic ray spallation, and potentially from other processes. They are the stable nuclides plus the long-lived fraction of radionuclides surviving in the primordial solar nebula through planet accretion until the present; 286 such nuclides are known.

Stability

All of the known 251 stable nuclides, plus another 35 nuclides that have half-lives long enough to have survived from the formation of the Earth, occur as primordial nuclides. These 35 primordial radionuclides represent isotopes of 28 separate elements.

Cadmium, tellurium, xenon, neodymium, samarium, osmium, and uranium each have two primordial radioisotopes (

Cd

,

Cd

;

Te

,

Te

;

Xe

,

Xe

;

Nd

,

Nd

;

Sm

,

Sm

;

Os

,

Os

; and

U

,

U

).

Because the age of the Earth is 4.58×10 years (4.6 billion years), the half-life of the given nuclides must be greater than about 10 years (100 million years) for practical considerations. For example, for a nuclide with half-life 6×10 years (60 million years), this means 77 half-lives have elapsed, meaning that for each mole (6.02×10 atoms) of that nuclide being present at the formation of Earth, only 4 atoms remain today.

The seven shortest-lived primordial nuclides (i.e., the nuclides with the shortest half-lives) to have been experimentally verified are

Rb

(5.0×10 years),

Re

(4.1×10 years),

Lu

(3.8×10 years),

Th

(1.4×10 years),

U

(4.5×10 years),

K

(1.25×10 years), and

U

(7.0×10 years).

These are the seven nuclides with half-lives comparable to, or somewhat less than, the estimated age of the universe. (Rb, Re, Lu, and Th have half-lives somewhat longer than the age of the universe.) For a complete list of the 35 known primordial radionuclides, including the next 28 with half-lives much longer than the age of the universe, see the complete list below. For practical purposes, nuclides with half-lives much longer than the age of the universe may be treated as if they were stable. Rb, Re, Lu, Th, and U have half-lives long enough that their decay is limited over geological time scales; K and U have shorter half-lives and are hence severely depleted, but are still long-lived enough to persist significantly in nature.

The longest-lived isotope not proven to be primordial is

Sm

, which has a half-life of 1.03×10 years, followed by

Pu

(8.08×10 years) and

Nb

(3.5×10 years). Pu was reported to exist in nature as a primordial nuclide in 1971, but this detection could not be confirmed by further studies in 2012 and 2022.

Taking into account that all these nuclides must exist for at least 4.6×10 years, Sm must survive 45 half-lives (and hence be reduced by 2 ≈ 4×10), Pu must survive 57 (and be reduced by a factor of 2 ≈ 1×10), and Nb must survive 130 (and be reduced by 2 ≈ 1×10). Mathematically, considering the likely initial abundances of these nuclides, primordial Sm and Pu should persist somewhere within the Earth today, even if they are not identifiable in the relatively minor portion of the Earth's crust available to human assays, while Nb and all shorter-lived nuclides should not. Nuclides such as Nb that were present in the primordial solar nebula but have long since decayed away completely are termed extinct radionuclides if they have no other means of being regenerated. As for Pu, calculations suggest that as of 2022, sensitivity limits were about one order of magnitude away from detecting it as a primordial nuclide.

Because primordial chemical elements often consist of more than one primordial isotope, there are only 83 distinct primordial chemical elements. Of these, 80 have at least one observationally stable isotope and three additional primordial elements have only radioactive isotopes (bismuth, thorium, and uranium).

Naturally occurring nuclides that are not primordial

Some unstable isotopes which occur naturally (such as

C

,

H

, and

Pu

) are not primordial, as they must be constantly regenerated. This occurs by cosmic radiation (in the case of cosmogenic nuclides such as

C

and

H

), or (rarely) by such processes as geonuclear transmutation (neutron capture of uranium in the case of

Np

and

Pu

). Other examples of common naturally occurring but non-primordial nuclides are isotopes of radon, polonium, and radium, which are all radiogenic nuclide daughters of uranium decay and are found in uranium ores. The stable argon isotope Ar is actually more common as a radiogenic nuclide than as a primordial nuclide, forming almost 1% of the Earth's atmosphere, which is regenerated by the beta decay of the extremely long-lived radioactive primordial isotope K, whose half-life is on the order of a billion years and thus has been generating argon since early in the Earth's existence. (Primordial argon was dominated by the alpha process nuclide Ar, which is significantly rarer than Ar on Earth.)

A similar radiogenic series is derived from the long-lived radioactive primordial nuclide Th. These nuclides are described as geogenic, meaning that they are decay or fission products of uranium or other actinides in subsurface rocks. All such nuclides have shorter half-lives than their parent radioactive primordial nuclides. Some other geogenic nuclides do not occur in the decay chains of Th, U, or U but can still fleetingly occur naturally as products of the spontaneous fission of one of these three long-lived nuclides, such as Sn, which makes up about 10 of all natural tin. Another, Tc, has also been detected. There are five other long-lived fission products known.

Primordial elements

"Primordial element" redirects here. For a concept in algebra, see Primordial element (algebra).A primordial element is a chemical element with at least one primordial nuclide. There are 251 stable primordial nuclides and 35 radioactive primordial nuclides, but only 80 primordial stable elements—hydrogen through lead, atomic numbers 1 to 82, except for technetium (43) and promethium (61)—and three radioactive primordial elements—bismuth (83), thorium (90), and uranium (92). If plutonium (94) turns out to be primordial (specifically, the long-lived isotope Pu), then it would be a fourth radioactive primordial, though practically speaking it would still be more convenient to produce synthetically. Bismuth's half-life is so long that it is often classed with the 80 stable elements instead, since its radioactivity is not a cause for concern. The number of elements is smaller than the number of nuclides, because many of the primordial elements are represented by multiple isotopes. See chemical element for more information.

Naturally occurring stable nuclides

As noted, these number about 251. For a list, see the article list of elements by stability of isotopes. For a complete list noting which of the "stable" 251 nuclides may be in some respect unstable, see list of nuclides and stable nuclide. These questions do not impact the question of whether a nuclide is primordial, since all "nearly stable" nuclides, with half-lives longer than the age of the universe, are also primordial.

Radioactive primordial nuclides

Though it is estimated that about 35 primordial nuclides are radioactive (list below), it becomes very hard to determine the exact total number of radioactive primordials, because the total number of stable nuclides is uncertain. There are many extremely long-lived nuclides whose half-lives are still unknown; in fact, all nuclides heavier than dysprosium-164 are theoretically radioactive. For example, it is predicted theoretically that all isotopes of tungsten, including those indicated by even the most modern empirical methods to be stable, must be radioactive and can alpha decay, but as of 2013 this could only be measured experimentally for W. Likewise, all four primordial isotopes of lead are expected to decay to mercury, but the predicted half-lives are so long (some exceeding 10 years) that such decays could hardly be observed in the near future. Nevertheless, the number of nuclides with half-lives so long that they cannot be measured with present instruments—and are considered from this viewpoint to be stable nuclides—is limited. Even when a "stable" nuclide is found to be radioactive, it merely moves from the stable to the unstable list of primordials, and the total number of primordial nuclides remains unchanged. For practical purposes, these nuclides may be considered stable for all purposes outside specialized research.

List of 35 radioactive primordial nuclides and measured half-lives

These 35 primordial radionuclides are isotopes of 28 elements (cadmium, neodymium, osmium, samarium, tellurium, uranium, and xenon each have two primordial radioisotopes). These nuclides are listed in order of decreasing stability. Many of them are so nearly stable that they compete for abundance with stable isotopes of their respective elements. For three elements (indium, tellurium, and rhenium) a very long-lived radioactive primordial nuclide is more abundant than a stable nuclide.

The longest-lived radionuclide known, Te, has a half-life of 2.2×10 years: 1.6 × 10 times the age of the Universe. Only four of these 35 nuclides have half-lives shorter than, or equal to, the age of the universe. Most of the other 30 have half-lives much longer. The shortest-lived primordial, U, has a half-life of 703.8 million years, about 1/6 the age of the Earth and Solar System. Many of these nuclides decay by double beta decay, though some like Bi decay by other means such as alpha decay.

At the end of the list, are two more nuclides: Sm and Pu. They have not been confirmed as primordial, but their half-lives are long enough that minute quantities should persist today.

| No. | Nuclide | Energy | Half- life (years) |

Decay mode |

Decay energy (MeV) |

Approx. ratio half-life to age of universe |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 252 | Te | 8.743261 | 2.2×10 | 2 β | 2.530 | 160 trillion |

| 253 | Xe | 8.778264 | 1.8×10 | KK | 2.864 | 1.3 trillion |

| 254 | Kr | 9.022349 | 9.2×10 | KK | 2.846 | 670 billion |

| 255 | Xe | 8.706805 | 2.165×10 | 2 β | 2.462 | 160 billion |

| 256 | Ge | 9.034656 | 1.8×10 | 2 β | 2.039 | 130 billion |

| 257 | Ba | 8.742574 | 1.2×10 | KK | 2.620 | 87 billion |

| 258 | Se | 9.017596 | 1.1×10 | 2 β | 2.995 | 8.0 billion |

| 259 | Cd | 8.836146 | 3.102×10 | 2 β | 2.809 | 2.3 billion |

| 260 | Ca | 8.992452 | 2.301×10 | 2 β | 4.274, .0058 | 1.7 billion |

| 261 | Bi | 8.158689 | 2.01×10 | α | 3.137 | 1.5 billion |

| 262 | Zr | 8.961359 | 2.0×10 | 2 β | 3.4 | 1.5 billion |

| 263 | Nd | 8.562594 | 9.3×10 | 2 β | 3.367 | 671 million |

| 264 | Te | 8.766578 | 8.806×10 | 2 β | .868 | 640 million |

| 265 | Mo | 8.933167 | 7.07×10 | 2 β | 3.035 | 510 million |

| 266 | Eu | 8.565759 | 4.62×10 | α | 1.9644 | 333 million |

| 267 | W | 8.347127 | 1.801×10 | α | 2.509 | 130 million |

| 268 | V | 9.055759 | 1.4×10 | β or β | 2.205, 1.038 | 10 million |

| 269 | Hf | 8.392287 | 7.0×10 | α | 2.497 | 5.1 million |

| 270 | Cd | 8.859372 | 7.7×10 | β | .321 | 560,000 |

| 271 | Sm | 8.607423 | 7.005×10 | α | 1.986 | 510,000 |

| 272 | Nd | 8.652947 | 2.292×10 | α | 1.905 | 170,000 |

| 273 | Os | 8.302508 | 2.002×10 | α | 2.823 | 150,000 |

| 274 | In | 8.849910 | 4.41×10 | β | .499 | 32,000 |

| 275 | Gd | 8.562868 | 1.08×10 | α | 2.203 | 7,800 |

| 276 | Os | 8.311850 | 1.12×10 | α | 2.963 | 810 |

| 277 | Pt | 8.267764 | 4.83×10 | α | 3.252 | 35 |

| 278 | Sm | 8.610593 | 1.061×10 | α | 2.310 | 7.7 |

| 279 | La | 8.698320 | 1.021×10 | β or K or β | 1.044, 1.737, 1.737 | 7.4 |

| 280 | Rb | 9.043718 | 4.972×10 | β | .283 | 3.6 |

| 281 | Re | 8.291732 | 4.122×10 | β | .0026 | 3.0 |

| 282 | Lu | 8.374665 | 3.764×10 | β | 1.193 | 2.7 |

| 283 | Th | 7.918533 | 1.405×10 | α or SF | 4.083 | 1.0 |

| 284 | U | 7.872551 | 4.468×10 | α or SF or 2 β | 4.270 | 0.32 |

| 285 | K | 8.909707 | 1.251×10 | β or K or β | 1.311, 1.505, 1.505 | 0.091 |

| 286 | U | 7.897198 | 7.038×10 | α or SF | 4.679 | 0.051 |

| 287 | Sm | 8.626136 | 9.20×10 | α | 2.529 | 0.0067 |

| 288 | Pu | 7.826221 | 8.00×10 | α or SF | 4.666 | 0.0058 |

List legends

- No. (number)

- A running positive integer for reference. These numbers may change slightly in the future since there are 251 nuclides now classified as stable, but which are theoretically predicted to be unstable (see Stable nuclide § Still-unobserved decay), so that future experiments may show that some are in fact unstable. The number starts at 252, to follow the 251 (observationally) stable nuclides.

- Nuclide

- Nuclide identifiers are given by their mass number A and the symbol for the corresponding chemical element (implies a unique proton number).

- Energy

- Mass of the average nucleon of this nuclide relative to the mass of a neutron (so all nuclides get a positive value) in MeV/c, formally: mn − mnuclide / A.

- Half-life

- All times are given in years.

- Decay mode

α α decay β β decay K electron capture KK double electron capture β β decay SF spontaneous fission 2 β double β decay 2 β double β decay I isomeric transition p proton emission n neutron emission - Decay energy

- Multiple values for (maximal) decay energy in MeV are mapped to decay modes in their order.

See also

- Alpha nuclide

- Table of nuclides sorted by half-life

- Table of nuclides

- Isotope geochemistry

- Radionuclide

- Mononuclidic element

- Monoisotopic element

- Stable isotope

- List of nuclides

- List of elements by stability of isotopes

- Big Bang nucleosynthesis

References

- Samir Maji; et al. (2006). "Separation of samarium and neodymium: a prerequisite for getting signals from nuclear synthesis". Analyst. 131 (12): 1332–1334. Bibcode:2006Ana...131.1332M. doi:10.1039/b608157f. PMID 17124541.

- Hoffman, D. C.; Lawrence, F. O.; Mewherter, J. L.; Rourke, F. M. (1971). "Detection of Plutonium-244 in Nature". Nature. 234 (5325): 132–134. Bibcode:1971Natur.234..132H. doi:10.1038/234132a0. S2CID 4283169.

- Lachner, J.; et al. (2012). "Attempt to detect primordial Pu on Earth". Physical Review C. 85 (1): 015801. Bibcode:2012PhRvC..85a5801L. doi:10.1103/PhysRevC.85.015801.

- ^ Wu, Yang; Dai, Xiongxin; Xing, Shan; Luo, Maoyi; Christl, Marcus; Synal, Hans-Arno; Hou, Shaochun (2022). "Direct search for primordial Pu in Bayan Obo bastnaesite". Chinese Chemical Letters. 33 (7): 3522–3526. doi:10.1016/j.cclet.2022.03.036. Retrieved 29 January 2024.

- P. K. Kuroda (1979). "Origin of the elements: pre-Fermi reactor and plutonium-244 in nature". Accounts of Chemical Research. 12 (2): 73–78. doi:10.1021/ar50134a005.

- Clark, Ian (2015). Groundwater geochemistry and isotopes. CRC Press. p. 118. ISBN 9781466591745. Retrieved 13 July 2020.

- H.-T. Shen; et al. "Research on measurement of Sn by AMS" (PDF). accelconf.web.cern.ch. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-11-25. Retrieved 2018-02-06.

- David Curtis, June Fabryka-Martin, Paul Dixon, Jan Cramer (1999), "Nature's uncommon elements: plutonium and technetium", Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 63 (2): 275–285, Bibcode:1999GeCoA..63..275C, doi:10.1016/S0016-7037(98)00282-8

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Interactive Chart of Nuclides (Nudat2.5)". National Nuclear Data Center. Retrieved 2009-06-22.

- ^ Kondev, F. G.; Wang, M.; Huang, W. J.; Naimi, S.; Audi, G. (2021). "The NUBASE2020 evaluation of nuclear properties" (PDF). Chinese Physics C. 45 (3): 030001. doi:10.1088/1674-1137/abddae.

- Chiera, Nadine M.; Sprung, Peter; Amelin, Yuri; Dressler, Rugard; Schumann, Dorothea; Talip, Zeynep (1 August 2024). "The Sm half-life re-measured: consolidating the chronometer for events in the early Solar System". Scientific Reports. 14 (1). doi:10.1038/s41598-024-64104-6. PMC 11294585.