| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Proscenium" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (October 2015) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

A proscenium (Ancient Greek: προσκήνιον, proskḗnion) is the metaphorical vertical plane of space in a theatre, usually surrounded on the top and sides by a physical proscenium arch (whether or not truly "arched") and on the bottom by the stage floor itself, which serves as the frame into which the audience observes from a more or less unified angle the events taking place upon the stage during a theatrical performance. The concept of the fourth wall of the theatre stage space that faces the audience is essentially the same.

It can be considered as a social construct which divides the actors and their stage-world from the audience which has come to witness it. But since the curtain usually comes down just behind the proscenium arch, it has a physical reality when the curtain is down, hiding the stage from view. The same plane also includes the drop, in traditional theatres of modern times, from the stage level to the "stalls" level of the audience, which was the original meaning of the proscaenium in Roman theatres, where this mini-facade was given more architectural emphasis than is the case in modern theatres. A proscenium stage is structurally different from a thrust stage or an arena stage, as explained below.

Origin

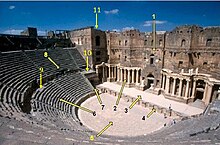

In later Hellenistic Greek theatres the proskenion (προσκήνιον) was a rather narrow raised stage where solo actors performed, while the Greek chorus and musicians remained in the "orchestra" in front and below it, and there were often further areas for performing from above and behind the proskenion, on and behind the skene. Skene is the Greek word (meaning "tent") for the tent, and later building, at the back of the stage from which actors entered, and which often supported painted scenery. In the Hellenistic period it became an increasingly large and elaborate stone structure, often with three storeys. In Greek theatre, which unlike Roman included painted scenery, the proskenion might also carry scenery.

In ancient Rome, the stage area in front of the scaenae frons (equivalent to the Greek skene) was known as the pulpitum, and the vertical front dropping from the stage to the orchestra floor, often in stone and decorated, as the proscaenium, again meaning "in front of the skene".

In the Greek and Roman theatre, no proscenium arch existed, in the modern sense, and the acting space was always fully in the view of the audience. However, Roman theatres were similar to modern proscenium theatres in the sense that the entire audience had a restricted range of views on the stage—all of which were from the front, rather than the sides or back.

Renaissance

The oldest surviving indoor theatre of the modern era, the Teatro Olimpico in Vicenza (1585), is sometimes incorrectly referred to as the first example of a proscenium theatre. The Teatro Olimpico was an academic reconstruction of a Roman theatre. It has a plain proscaenium at the front of the stage, dropping to the orchestra level, now usually containing "stalls" seating, but no proscenium arch.

However, the Teatro Olimpico's exact replication of the open and accessible Roman stage was the exception rather than the rule in sixteenth-century theatre design. Engravings suggest that the proscenium arch was already in use as early as 1560 at a production in Siena.

The earliest true proscenium arch to survive in a permanent theatre is the Teatro Farnese in Parma (1618), many earlier such theatres having been lost. Parma has a clearly defined "boccascena", or scene mouth, as Italians call it, more like a picture frame than an arch but serving the same purpose: to deineate the stage and separate the audience from its action.

Baroque

While the proscenium arch became an important feature of the traditional European theatre, often becoming very large and elaborate, the original proscaenium front below the stage became plainer.

The introduction of an orchestra pit for musicians during the Baroque era further devalued the proscaenium, bringing the lowest level of the audience's view forward to the front of the pit, where a barrier, typically in wood, screened the pit. What the Romans would have called the proscaenium is, in modern theatres with orchestra pits, normally painted black in order that it does not draw attention.

Confusion around Teatro Olimpico

In this early modern recreation of a Roman theatre, confusion seems to have been introduced to the use of the revived term in Italian. This emulation of the Roman model extended to refer to the stage area as the "proscenium", and some writers have incorrectly referred to the theatre's scaenae frons as a proscenium, and have even suggested that the central archway in the middle of the scaenae frons was the inspiration for the later development of the full-size proscenium arch. There is no evidence at all for this assumption (indeed, contemporary illustrations of performances at the Teatro Olimpico clearly show that the action took place in front of the scaenae frons and that the actors were rarely framed by the central archway).

The Italian word for a scaenae frons is "proscenio," a major change from Latin. One modern translator explains the wording problem that arises here: " we retain the Italian proscenio in the text; it cannot be rendered proscenium for obvious reasons; and there is no English equivalent ... It would also be possible to retain the classical frons scaenae. The Italian "arco scenico" has been translated as "proscenium arch."

In practice, however, the stage in the Teatro Olimpico runs from one edge of the seating area to the other, and only a very limited framing effect is created by the coffered ceiling over the stage and by the partition walls at the corners of the stage where the seating area abuts the floorboards. The result is that in this theatre "the architectural spaces for the audience and the action ... are distinct in treatment yet united by their juxtaposition; no proscenium arch separates them."

Function

A proscenium arch creates a "window" around the scenery and performers. The advantages are that it gives everyone in the audience a good view because the performers need only focus on one direction rather than continually moving around the stage to give a good view from all sides. A proscenium theatre layout also simplifies the hiding and obscuring of objects from the audience's view (sets, performers not currently performing, and theatre technology). Anything that is not meant to be seen is simply placed outside the "window" created by the proscenium arch, either in the wings or in the flyspace above the stage. The phrase "breaking the proscenium" or "breaking the fourth wall" refers to when a performer addresses the audience directly as part of the dramatic production.

Proscenium theatres have fallen out of favor in some theatre circles because they perpetuate the fourth wall concept. The staging in proscenium theatres often implies that the characters performing on stage are doing so in a four-walled environment, with the "wall" facing the audience being invisible. Many modern theatres attempt to do away with the fourth wall concept and so are instead designed with a thrust stage that projects out of the proscenium arch and "reaches" into the audience (technically, this can still be referred to as a proscenium theatre because it still contains a proscenium arch, but the term thrust stage is more specific and more widely used).

In dance history, the use of the proscenium arch has affected dance in different ways. Prior to the use of proscenium stages, early court ballets took place in large chambers where the audience members sat around and above the dance space. The performers, often led by the queen or king, focused in symmetrical figures and patterns of symbolic meaning. Ballet's choreographic patterns were being born. In addition, since dancing was considered a way of socializing, most of the court ballets finished with a ‘grand ballet’ followed by a ball in which the members of the audience joined the performance.

Later on, the use of the proscenium stage for performances established a separation of the audience from the performers. Therefore, more devotion was placed on the performers, and in what was occurring in the ‘show.’ It was the beginning of dance-performance as a form of entertainment like we know it today. Since the use of the proscenium stages, dances have developed and evolved into more complex figures, patterns, and movements. At this point, it was not only significantly important how the performers arrived to a certain shape on the stage during a performance, but also how graciously they executed their task. Additionally, these stages allowed for the use of stage effects generated by ingenious machinery. It was the beginning of scenography design, and perhaps also it was also the origin of the use of backstage personnel or "stage hands".

Other forms of theatre staging

- Traverse stage: The stage is surrounded on two sides by the audience.

- Thrust stage: The stage is surrounded on three sides (or 270°) by audience. Can be a modification of a proscenium stage. Sometimes known as "three quarter round". Also known as an apron stage.

- Theatre in the round: The stage is surrounded by audience on all sides.

- Black box theatre: The theatre is a large rectangular room with black walls and a flat floor. The seating is typically composed of loose chairs on platforms, which can be easily moved or removed to allow the entire space to be adapted to the artistic elements of a production.

- Site-specific theatre (a.k.a. environmental theatre): The stage and audience either blend together, or are in numerous or oddly shaped sections. Includes any form of staging that is not easily classifiable under the above categories.

References

- Boardman, John ed., The Oxford History of Classical Art, p. 168, 1993, OUP, ISBN 0198143869

- Licisco Magagnato, "The Genesis of the Teatro Olimpico, in Journal of the Warburg and Courtald Institutes, Vol. XIV (1951), p. 215.

- Licisco Magagnato, "The Genesis of the Teatro Olimpico, in Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, Vol. XIV (1951), p. 215.

- Translator's note in Licisco Magagnato, "The Genesis of the Teatro Olimpico, in Journal of the Warburg and Courtald Institutes, Vol. XIV (1951), p. 213.

- Caroline Constant, "The Palladio Guide". Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton Architectural Press, 1985, p. 16.

External links

- Scenography - The Theatre Design Website Diagram and images of proscenium stage