United Kingdom enterprise law concerns the ownership and regulation of organisations producing goods and services in the UK, European and international economy. Private enterprises are usually incorporated under the Companies Act 2006, regulated by company law, competition law, and insolvency law, while almost one third of the workforce and half of the UK economy is in enterprises subject to special regulation. Enterprise law mediates the rights and duties of investors, workers, consumers and the public to ensure efficient production, and deliver services that UK and international law sees as universal human rights. Labour, company, competition and insolvency law create general rights for stakeholders, and set a basic framework for enterprise governance, but rules of governance, competition and insolvency are altered in specific enterprises to uphold the public interest, as well as civil and social rights. Universities and schools have traditionally been publicly established, and socially regulated, to ensure universal education. The National Health Service was set up in 1946 to provide everyone with free health care, regardless of class or income, paid for by progressive taxation. The UK government controls monetary policy and regulates private banking through the publicly owned Bank of England, to complement its fiscal policy. Taxation and spending composes nearly half of total economic activity, but this has diminished since 1979.

Since 1980, a large segment of UK enterprise was privatised, reducing public and citizen voice in their services, particularly among utilities. Since the Climate Change Act 2008, the modern UK economy has increasingly been powered by renewable energy, but still depends disproportionately on oil, gas and coal. Energy governance is framed by statutes including the Petroleum Act 1998 and the Electricity Act 1989, which enable government to use its licensing powers to shift to a zero-carbon economy, and phase out fossil fuels. Energy ratepayers typically have rights to adequate standards of supply, and increasingly the right to participate in how their services are provided, overseen by the Oil and Gas Authority and Ofgem. The Water Industry Act 1991 regulates drinking and sewerage infrastructure, overseen by Ofwat. The Railways Act 1993, the Transport Act 1985 or the Road Traffic Act 1988, under the Office of Rail and Road, govern the majority of land transport. Rail and bus passengers are entitled to adequate services, and have limited rights to voice in management. A growing number of bus, energy and water enterprises have been put back into public hands, while in London and Scotland, railways may be wholly publicly run. While, post, telephones and television were the major channels for communication and media in the 20th century, 21st century communications networks have increasingly converged on the Internet. Particularly in social media networks, this has presented problems in ensuring standards of safety, accuracy and fairness in online information and discourse. Like securities and other marketplaces, online networks dominated by multinational corporations, have received increased attention from regulators and legislators as they have become associated with political crisis.

History

Further information: Nationalisation and Privatisation- Aristotle, Plato, Roman law and the societas

- Otto von Gierke

- Magna Carta and Lex Mercatoria

- Sidney Webb

- House of Medici, Medici Bank, Pope Leo X (1513–1521), Pope Clement VII (1523–1534), Pope Leo XI (1605)

- Sir Thomas More, Utopia (1535) and John Locke (1689)

- Bank of England

- South Sea Company

- Port of London Act 1908

- National Insurance Act 1911

- Railways Act 1921

- WA Robson, ‘The Public Corporation in Britain Today’ (1950) 63(8) Harvard Law Review 1321

- Bank of England Act 1946

- National Health Service Act 1946

- Transport Act 1947

- Electricity Act 1947

- Gas Act 1986

General enterprise law

See also: UK commercial law, English contract law, English tort law, English trusts law, and English land lawWhile the 20th century had seen swings from nationalisation and re-privatisation, a general law of enterprise developed where private ownership and markets were generally thought to work by themselves. On top of ordinary principles of commercial law, based on contract, property, tort, and trusts, four main fields of law settled the rights and duties of enterprise stakeholders. First, UK company law determines the constitution, governance and finance of major corporations. Much of the Companies Act 2006 concerns the duties of company directors, and the rights of members, who are usually registered as holding share capital. Equity investment mostly derives from people saving for retirement in mutual funds, life insurance and pensions. Second, UK labour law structures the rights of employees and their representative unions against the management of an enterprise. Employees are entitled to a minimum floor of rights, and to rights of voice through collective bargaining or occasionally votes at work in their enterprise. Third, competition law, which is closely coordinated with EU law aims to protect consumers' and the public interest in choice in markets, particularly where enterprise is privately owned. Fourth, UK insolvency law determines the relative rights of creditors when an enterprise can no longer pay its debts when they fall due. All enterprises are subject to general duties under UK environmental law and criminal law.

Corporate governance

Main articles: UK company law, European company law, and US corporate law- Companies Act 2006 ss 21, 112, 168 and 284, company constitutions, amendment, voting rights and removal of directors

- Model Articles, Sch 3, paras 3 and 34, model articles for public companies

- Companies Act 2006 ss 170–177, 260–263 and 419 (directors’ duties, derivative claims, report)

- Pensions Act 2004 ss 241–243, right of pension beneficiaries to nominate pension trustees

- Charities Act 2006

Labour rights

Main articles: UK labour law, European labour law, and US labor law- Autoclenz Ltd v Belcher UKSC 41, minimum wage and working time claims

- Trade Union and Labour Relations (Consolidation) Act 1992 ss 179, 219, 224, 244 (collective agreements not legally binding, immunity from damages for collective action in contemplation or furtherance of a trade dispute, no secondary action, meaning of a trade dispute)

- ECHR article 11

- RMT v United Kingdom ECHR 366, secondary action

- Health and Safety Executive

Competition and consumers

Main articles: UK competition law, EU competition law, and US antitrust law- TFEU arts 101 and 102

- Competition Act 1998 ss 2–3, 18–19 and Sch 3, prohibition of abuse of a dominant position and collusion

- TFEU arts 106(2) and 345, state aid and neutrality to public ownership

- Albany International BV v Stichting Bedrijfspensioenfonds Textielindustrie (1999) C-67/96

- Public procurement

- State aid

- Consumer Rights Act 2015

- Sale of Goods Act 1979

- Consumer cooperative

- Consumer Protection Act 1987

- Environmental Protection Act 1990

Insolvency

Main articles: UK insolvency law, Cross-border insolvency, and US bankruptcy law- Insolvency Act 1986 ss 175-176A and Sch 6, preferential rights in insolvency for employees and pensions

- Re Spectrum Plus Ltd UKHL 41, interpretation of a ‘floating charge’

- Insolvency Act 1986 Sch B1, paras 3, 14, 22 and 36, governance in administering insolvent companies

Specific enterprises

See also: UK constitutional lawWhile many sectors of the economy function under general rules of enterprises alone, specific enterprise laws developed where "free markets" were seen as inadequate to protect consumer or public interests. In enterprises that concerned central social and economic rights, were "network" or "natural monopolies", for "public goods", or where significant capital investment was necessary, the UK law developed specific rules. Usually, a combination of public ownership, positive rights of voice for users or citizens, or sector-specific regulators emerged. These regulate the rights of exit, basic standards, and voice of stakeholders, beyond investors of capital or labour.

Education

See also: Universities in the UK, Education in the UK, and Education in England| University sources | |

|---|---|

| UDHR 1948 art 26 | |

| European Social Charter 1961 arts 7, 10 and 17 | |

| ECHR 1950 Prot 1, art 2 | |

| Belgian Linguistic case (No 2) (1968) 1 EHRR 252 | |

| Further and Higher Education Act 1992 ss 62-69, 81, and 89 | |

| Higher Education Act 2004 ss 23-24 and 31-39 | |

| R (Bidar) v London Borough of Ealing (2005) C-209/03 | |

| Education Reform Act 1988 ss 124A, 128, Schs 7 and 7A, para 3 | |

| Oxford University Act 1854 ss 16 and 21 | |

| Cambridge University Act 1856 ss 5 and 12 | |

| King’s College London Act 1997 s 15 | |

| Clark v University of Lincolnshire EWCA Civ 129 | |

| R (Persaud) v University of Cambridge EWCA Civ 534 | |

| see UK enterprise law |

The Universal Declaration, the International Bill of Human Rights and the European Social Charter say that "everyone" has the right to education, and that primary, secondary and higher education should be made "free", in particular "by reducing or abolishing any fees or charges" and "granting financial assistance". Historically, the UK guaranteed free childhood, higher and adult education, and gave grants until the late 20th century. However, it maintained a private fee-paying school system, dependent on parents paying money (also called "private" or "public" schools, after the Public Schools Act 1868). Following this model, the Teaching and Higher Education Act 1998 re-instated tuition fees for university. Although the evidence suggests that fees deter and disadvantage poorer people, university fees were raised to £9250 a year from 2017 in England and Wales. Scotland remained tuition free. University and school finance and governance remains a patchwork system across the UK, without any coherent approach.

Universities have three main sources of finance. First, universities may generate income through endowment trust funds, accumulated over generations of donations and investment. Second, under the Further and Higher Education Act 1992 there are funding councils paid for through general taxation for England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland. For England and Wales, the Secretary of State appoints twelve to fifteen members and the chair, of which six to nine should be academics and the remainder with "industrial, commercial or financial" backgrounds. Funds are administered at the funding councils' discretion but must consult with "bodies representing the interests of higher education institutions" such as the University and College Union and Universities UK. Further, there are seven research councils (AHRC, ESRC, MRC, etc.) which distribute funds after peer review of applications by academics conducting research. Third, and most controversially, most funding comes from charging students fees. After the Second World War, tuition fees in the UK were effectively abolished and local authorities paid maintenance grants. The Education Act 1962 formally required this position for all UK residents, and this continued through the expansion of university places recommended by the Robbins Report of 1963. However, over the 1980s and 1990s, grants were diminished, requiring students to become ever more reliant on their parents' wealth. Further, appointed in 1996, the Dearing Report argued for the introduction of tuition fees because it said graduates had "improved employment prospects and pay." Instead of funding university through progressive tax, the Teaching and Higher Education Act 1998 permitted £1,000 fees for home students. In England, this rose to £3,000 in the Higher Education Act 2004, and £9,000 after the Browne Review in 2010 led by the former CEO of oil corporation BP. In 2017, the limit on fees was £9,250 for students in England, £9,000 in Wales, and £3,805 in Northern Ireland. Until "Brexit", the same rates applied for EU students, who could be discriminated against under EU law, but after 2020 EU students were charged at international fee rates. By contrast, the Scottish government resolved not to introduce tuition fees for students under 25. For English universities, the Higher Education Act 2004 enables the Secretary of State to set fee limits, while universities are meant to ensure "fair access" by drafting a "plan" for "equality of opportunity". There is no limit on international students fees, which are often double or triple home student fee rates, and universities aim to boost international student numbers to get more fees. A system of student loans is available for UK students through the government-owned Student Loans Company. Means-tested grants were also available, but abolished for students who began university after August 2016. Students typically qualify for loans (or previously grants) if they have been resident for three years in the UK. As the UK is in a minority of countries to still charge tuition fees, increasing demands have been made to abolish fees on the ground that they burden people without wealthy families in debt, deter disadvantaged students from education, and escalate income inequality.

Governance of universities is set by each university's constitution, typically deriving from an Act of Parliament, a royal charter or an Order in Council issued by the Privy Council. The most progressive models support a high degree of voice for staff and students. Reforms were first put into law after the Oxford University Commission of 1852 stated it must reverse "successive interventions by which the government of the University was reduced to a narrow oligarchy." For example, since the Cambridge University Act 1856 set its rules in law, Cambridge University's statutes require that its Regent House (mostly full-time university members) elects its governing body, the 23 member council. Four members are elected by heads of colleges, four by professors and readers, eight by other academic fellows, three by students, four by a "grace" (a vote) of the whole Regent House. Other universities have a broad variety of governance structures, although if there is not a special statute or constitution, the highly minimalist rules are set by the Education Reform Act 1988. This says that university governing bodies with constitutions issued by the Privy Council should have between 12 and 24 members, with up to thirteen lay members, up to two teachers, up to two students, and between one and nine members co-opted by the others. Universities are subject to both judicial review and students may enforce rights through contract law since universities are seen as having both an equally "public" and "private" nature. In a leading case of Clark v University of Lincolnshire and Humberside a student claimed that she should not have received a third class degree after her computer crashed, she lost an assignment, and was forced to rush a new one. The Court of Appeal held that her application for both breach of contract and judicial review should not be struck out because there could be a good case to hear, so long as it did seek to overturn "issues of academic or pastoral judgment" where "any judgment of the courts would be jejune and inappropriate". However, the shorter time limit of three months in judicial review was more appropriate than six years in contract. Cases which have sought to challenge academic judgment for failing students are typically bound to fail, as grading with a fair process is in the bounds of academic judgment. In Buckland v Bournemouth University, where the university management interfered with the academic assessment of student grades, this founded a right for a professor to claim he was constructively and unfairly dismissed. All access to education must be free from unlawful discrimination under the Equality Act 2010.

- Schools

There are at least five different kinds of school: comprehensive schools that are publicly owned and run, grammar schools in some counties that have selective admissions, academies that are mainly public but enable some private contributions and governance, and private fee-paying schools that depend on charging parents money for tuition. Some schools also apply for "specialist" status if they focus on particular curriculum topics.

- Labour of Children, etc., in Factories Act 1833

- Public Schools Act 1868, following the Clarendon Commission removed charity schools from government or education department oversight, and now the main UK private schools

- Elementary Education Act 1870, five to twelve-year-olds, school boards providing universal primary education

- Education Act 1902, abolished 2,568 school boards and instituted 328 local education authorities in their place, following the Cockerton judgment

- Education (Provision of Meals) Act 1906, introduced free school meals

- Education (Administrative Provisions) Act 1907, medical services

- Education Act 1918, school leaving age raised to fourteen years, maximum class size of thirty

- Education Act 1944, attempted foundation of a tripartite secondary school system, every child got free school meals, until 1949 when it was 2.5 pence

- Education Reform Act 1988, schools could remove themselves from LEA oversight and become "grant-maintained" by central government, headteachers getting financial control, academic tenure abolished, national curriculum with key stages, league tables

- Education Act 1996, teacher training, and opt-out from students' unions

- School Standards and Framework Act 1998, thirty infant pupil class size limit, replaced "grant-maintained schools" with "foundation status" meaning money is channelled from central government through the LEA, restrictions on selection

- Learning and Skills Act 2000 and Education Act 2002 and Academies Act 2010, allowed for academies outside national curriculum and autonomy over teacher pay

- Education Act 2005, Ofsted inspections

- Education and Inspections Act 2006, trust schools

- General Teaching Councils and code

- Libraries

Health and care

| Public health sources | |

|---|---|

| UDHR 1948 art 25 | |

| European Social Charter 1961 arts 11 and 13 | |

| ECHR 1950 arts 2, 3 and 8 | |

| National Health Service Act 2006 ss 1-1I, Sch 1A and Sch 7 | |

| NHS (Clinical Commissioning Groups) Regulations 2012 regs 11-12 | |

| Health and Social Care Act 2012 ss 75, 115-121 and 165 | |

| NHS (Procurement, Patient Choice and Competition) (No 2) Regulations 2013 regs 2-11 | |

| National Health Service (Private Finance) Act 1997 s 1 | |

| National Health Service Act 2006 ss 1A-C and 3 | |

| R (B) v Cambridge Health Authority EWCA Civ 43 | |

| R (Coughlan) v North and East Devon HA EWCA Civ 1871 | |

| R (Ann Marie Rogers) v Swindon PCT EWCA Civ 392 | |

| R (Watts) v Bedford Primary Care Trust (2006) C-372/04 | |

| National Health Service Act 2006 ss 6BB and 175 | |

| NHS (Charges to Overseas Visitors) Regulations 2015 regs 3-9 | |

| N v United Kingdom ECHR 453 | |

| see UK enterprise law |

Like education, there is a universal right to "health and well-being" including "medical care and necessary social services". The National Health Service, founded in 1946, has consistently been seen as one of the most important aspects of the UK's constitution, and goes considerably beyond international human rights standards. Its founding principle, that everyone should receive health care free, as a right, is usually seen as politically "untouchable", and is consistently rated as the UK's most popular institution. However, the details of funding and governing health have been volatile and contested. The UK has among the world's highest life expectancy (82.8 years in 2015), but spends a relatively low amount of money on its service (9.7 per cent of GDP in 2016). Since the Health and Social Care Act 2012 changed its governance, health care expenditure rose dramatically without visible health gains. The National Health Service is funded directly by the UK Treasury from general taxation, which requires no citizen to buy insurance, or pay upfront costs (except for capped, and means tested prescription charges for medicines, dental and optical service in England. Scotland, Wales or Northern Ireland scrapped prescription charges). According to the NHS Constitution for England art 1(2), "Access to NHS services is based on clinical need, not an individual's ability to pay". Health care is a devolved matter, but each country of the UK organised its health system following the model in the proposals of the landmark Beveridge Report of 1942. The Beveridge model of health provision, common to countries like Denmark, Sweden or Greece, removed the requirement of contributions by workers under the National Insurance Act 1911. Insurance systems continue in countries like France, Germany, or the United States. As the UK government bears the cost of health care, and the potential to profit from people being ill is eliminated, the government has a strong incentive to improve public health with measures like the Public Health Act 1961, the Health and Safety at Work Act 1974, or the Environmental Protection Act 1990.

National Health Service governance has seen three phases of change. While the NHS Constitution states patients and staff should be "involved" and "engaged", the actual right of stakeholders to vote has been slow. First, and originally, the NHS Act 1946 created a system of 14 regional hospital boards that would pay for staff, buildings and equipment at hospitals, and gave grants to local health authorities in each council which ran health centres overseen by "executive councils". The Minister of Health (with Whitehall civil servants) appointed the regional boards, while executive councils and local health authorities were medical professional representatives (though not necessarily elected), local government and Minister appointees. In 1973, regional hospital boards were renamed regional health authorities, and 90 area health authorities plus 205 district health authorities took over from the more numerous local health authorities, while the government aimed to give stakeholders more direct voting rights in all. Second, from the NHS and Community Care Act 1990 health authorities had to predict and account for their spending, and contract for their purchases of medical services from NHS trusts, which would compete among one another to sell health services. This did not yet mean that private companies could also compete, although the NHS (Private Finance) Act 1997 enabled the Secretary of State to approve "private finance initiative" schemes to borrow money for, or lease, the building and running of health facilities from private contractors (e.g. Telereal Trillium Ltd, Innisfree Ltd or HSBC Infrastructure Co Ltd). From 1995 to 2006 a new NHS Executive was created to manage the NHS in England, but was reabsorbed into the Department of Health. The executive or department oversaw strategic health authorities (28 reduced to 10), and primary care trusts (303 reduced to 101) which provided health services, and bought or "commissioned" "secondary care" health services (e.g. from a specialist doctor). From 2003, NHS foundation trusts were created, which could borrow money without Department of Health approval. Under the National Health Service Act 2006 Schedule 7, its "council of governors" must have a constitution where at least three governors (but under half) must be elected by the foundation trust's employees, at least one by nearby local authorities, one by a university (if any) in the area. A trust's constitution is free to enable residents, employees or patients to vote, although the law does not fix rules. Third, instead of enabling NHS Foundation Trusts to take purchasing in-house, the Health and Social Care Act 2012 set up around 200 clinical commissioning groups (CCGs) to replace primary care trusts. CCGs are funded and mediated by NHS England. According to the HSCA 2012, a clinical commissioning group is a "body corporate" that should buy services, with members who can set pay for themselves. A CCG must include at least six members (many came from abolished primary care trusts, general practitioners or private business), with one person qualified in accounting or finance, a nurse, a secondary care specialist, and two lay people who understand finance and the local area. Two central features of the Health and Social Care Act 2012 were that section 75 required commissioning was subjected to competition law (i.e. CCGs are potentially unable to cooperate to bargain down drug company prices, etc.), and section 165 enabled NHS foundation trusts to derive up to 49% of their income from private work. In theory, clinical commissioning groups are meant not to discriminate, seek the best "value for money" and avoid conflicts of interest when buying services. However, the enforcement of the prohibition on conflicts of interest requires costly judicial review, while derivative claims by patients or staff are excluded without membership. Although CCGs are under a duty to "involve" patients and the public in decision-making, those stakeholders can be ignored because unlike in NHS foundation trusts they have no right to vote. The Care Quality Commission and a subordinate Healthwatch England network is meant to inspect and maintain standards.

Although rights to vote are lacking, patients have some rights to bring claims in court over levels of service. First, the Secretary of State for Health is meant to improve the "physical and mental health of the people" and "have regard to the need to reduce inequalities" in health. These duties, however, are difficult to enforce in practice because the courts give wide discretion to ministers in judicial review. Second, it is possible to sue in tort for medical negligence if operations go wrong. This is controversial because (unlike New Zealand's Accident Compensation Corporation) claims require litigation, and substantial sums of money go to lawyers, instead of the person who is harmed and withdraws resources for other NHS patients. Third, challenges can be brought over the refusal to provide treatment, although they are unlikely to succeed. For instance, in R (B) v Cambridge Health Authority parents claimed their 11-year-old girl should receive a second bone marrow transplant for myeloid leukemia, even though doctors said success was 20% likely and would cause "considerable suffering". Although Laws J held that refusal was inadequate, Sir Thomas Bingham MR held the health authority acted rationally and fairly. After the case, because of the tabloid campaign, a donor paid for £75,000 in private treatment, but the operation failed. By contrast in R (Coughlan) v North and East Devon HA Mrs Coughlan successfully claimed to remain at the "Mardon House" care home after an accident left her tetraplegic and she was promised it was a "home for life". Lord Woolf MR held in judicial review that the promise generated a "legitimate expectation" that was "equivalent to a breach of contract in private law", which could not be unilaterally withdrawn, even if the Secretary of State was concerned about cost. Further, in R (Ann Marie Rogers) v Swindon Primary Care Trust Sir Anthony Clarke MR held that a primary care trust's reasons for refusing Rogers Herceptin treatment for breast cancer were inadequate. This drug was yet not approved by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, but simply stating Rogers' case was not "exceptional" (as other people were refused the drug) was not a reason in itself, and its decision was therefore irrational. Within the European Union, British residents also have the right to move to other member states for treatment and be reimbursed if NHS waiting lists happen to be unreasonably long, assessed by objective criteria. For example, in R (Watts) v Bedford Primary Care Trust, Mrs Watts paid £3900 for a hip replacement operation in France after the NHS waiting lists were 4 to 6 months, and successfully claimed that she should be reimbursed by the NHS. But these rights to move for health and be reimbursed by the NHS may be removed if the UK leaves the EU and the single market. No charges can be applied by the NHS to people who are "ordinarily resident" in the UK, although controversially the Conservative government introduced a "duty" on hospitals and health services to charge overseas visitors if they fall sick. Given the tiny number of cases, most health services refused to charge patients even when they could, because of disproportionate bureaucratic cost, and compassion. Another issue of migration, is that a deportation of an illegal migrant is very unlikely to be delayed by ill-health. In N v United Kingdom, the European Court of Human Rights held that a citizen of Uganda had no right under ECHR article 3 to delay deportation, even though health treatment for HIV/AIDS was highly unlikely there. The UK, however, has the option at any time to improve its service beyond the minimum standards of human rights.

- Social care

- Social care in the United Kingdom, Social care in England, Social care in Scotland

- Care Standards Act 2000, the elderly and disabled

- National Health Service and Community Care Act 1990

- Children Act 1989 and orphanages

- Health and Social Care Act 2008

Banking

| Bank regulation sources | |

|---|---|

| Bank of England Act 1998 ss 1-2B, 11-13, 19 and Sch 1 | |

| TEU art 3(3) and TFEU arts 7, 119-150 and 283 | |

| Credit Institutions Directive 2013/36/EU arts 8-14, 35, 88-96 | |

| Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 ss 1A-E, 19-23, 418-9, Schs 2 and 6 | |

| Companies Act 2006 ss 168-9, 170-77, 260-263 | |

| CMAR 2008, Sch 3, paras 3-5 and 20-23 | |

| UK Corporate Governance Code 2016, sections A-E | |

| Foley v Hill (1848) 2 HLC 28 | |

| Vincent v Trustee Savings Banks Central Board 1 WLR 1077 | |

| Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 ss 214-215 | |

| Deposit Guarantee Directive 2014/49/EU | |

| Consumer Credit Act 1974 ss 140A-D | |

| Capital Requirements Regulation (EU) No 575/2013 | |

| Banking Act 2009 ss 1, 7-12 | |

| See UK enterprise law |

UK banking has two main parts. First, the Bank of England administers monetary policy, influencing interest rates, inflation and employment, and it regulates the banking market with HM Treasury, the Prudential Regulation Authority and Financial Conduct Authority. Second, there are private banks, and some non-shareholder banks (co-operatives, mutual or building societies), that provide credit to consumer and business clients. Borrowing money on credit (and repaying the debt later) is important for people to expand a business, invest in a new enterprise, or purchase valuable assets more quickly than by saving. Every day, banks estimate the prospects of a borrower succeeding or failing, and set interest rates for debt repayments according to their predictions of the risk (or average risk of ventures like it). If all banks together lend more money, this means enterprises will do more, potentially employ more people, and if business ventures are productive in the long run, society's prosperity will increase. If banks charge interest that people cannot afford, or if banks lend too much money to ventures that are unproductive, economic growth will slow, stagnate, and sometimes crash. Although UK banks, except the Bank of England, are shareholder or mutually owned, many countries operate public retail banks (for consumers) and public investment banks (for business). The UK used to run Girobank for consumers, and there have been many proposals for a "British Investment Bank" (like the Nordic Investment Bank or KfW in Germany) since the financial crisis of 2007–2008, but these proposals have not yet been accepted.

The Bank of England provides finance and support to, and may influence interest rates of the private banks through monetary policy. It was originally established as a corporation with private shareholders under the Bank of England Act 1694, to raise money for war with Louis XIV, King of France. After the South Sea Company collapsed in a speculative bubble in 1720, the Bank of England became the dominant financial institution, and acted as a banker to the UK government and other private banks. This meant, simply by being the biggest financial institution, it could influence interest rates that other banks charged to businesses and consumers by altering its interest rate for the banks' bank accounts. It also acted as a lender through the 19th century in emergencies to finance banks facing collapse. Because of its power, many believed the Bank of England should have more public duties and supervision. The Bank of England Act 1946 nationalised it. Its current constitution, and guarantees of a degree of operational independence from government, is found in the Bank of England Act 1998. Under section 1, the bank's executive body, the court of directors is "appointed by Her Majesty", which in effect is the prime minister. This includes the governor of the Bank of England (currently Mark Carney) and up to 14 directors in total (currently there are twelve, nine men and three women). The governor may serve for a maximum of eight years, deputy governors for a maximum of ten years, but they may be removed only if they acquire a political position, begin to work for the bank, are absent for over three months, become bankrupt, or "is unable or unfit to discharge his functions as a member". This makes removal hard, and potentially judicially reviewable. A sub-committee of directors sets pay for all directors, rather than a non-conflicted body like Parliament. The Bank's most important function is administering monetary policy. Under the Bank of England Act 1998 section 11 its objectives are to (a) "maintain price stability, and (b) subject to that, to support the economic policy of Her Majesty's Government, including its objectives for growth and employment." Under section 12, HM Treasury issues its interpretation of "price stability" and "economic policy" each year, together with an inflation target. To change inflation, the Bank of England has three main policy options. First, it performs "open market operations", buying and selling banks' bonds at differing rates (i.e. loaning money to banks at higher or lower interest, known "discounting"), buying back government bonds ("repos") or selling them, and giving credit to banks at differing rates. This will affect the interest rate banks charge by influencing the quantity of money in the economy (more spending by the central bank means more money, and so lower interest) but also may not. Second, the Bank of England may direct banks to keep different higher or lower reserves proportionate to their lending. Third, the Bank of England could direct private banks adopt specific deposit-taking or lending policies, in specified volumes or interest rates. The Treasury is, however, only meant to give orders to the Bank of England in "extreme economic circumstances". This should ensure that changes to monetary policy are undertaken neutrally, and artificial booms are not manufactured before an election.

Outside the central bank, banks are mostly run as profit-making corporations, without meaningful representation for customers. This means, the standard rules in the Companies Act 2006 apply. Directors are usually appointed by existing directors in the nomination committee, unless the members of a company (invariably shareholders) remove them by majority vote. Bank directors largely set their own pay, delegating the task to a remuneration committee of the board. Most shareholders are asset managers, exercising votes with other people's money that comes through pensions, life insurance or mutual funds, who are meant to engage with boards, but have few explicit channels to represent the ultimate investors. Asset managers rarely sue for breach of directors' duties (for negligence or conflicts of interest), through derivative claims. However, there is some public oversight through the bank licensing system. Under the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 section 19 there is a "general prohibition" on performing a "regulated activity", including accepting deposits from the public, without authority. The two main UK regulators are the Prudential Regulation Authority and the Financial Conduct Authority. Once a bank has received authorisation in the UK, or another member state, it may operate throughout the EU under the terms of the host state's rules: it has a "passport" giving it freedom of establishment in the internal market. Since the Credit Institutions Directive 2013, there are some added governance requirements beyond the general framework: for example, duties of directors must be clearly defined, and there should be a policy on board diversity to ensure gender and ethnic balance. If the UK had employee representation on boards, there would also be a requirement for at least one employee to sit on the remuneration committee, but this step has not yet been taken.

While banks perform an essential economic function, supported by public institutions, the rights of bank customers have generally been limited to contract. In general terms and conditions, customers receive very limited protection. The Consumer Credit Act 1974 sections 140A to 140D prohibit unfair credit relationships, including extortionate interest rates. The Consumer Rights Act 2015 sections 62 to 65 prohibit terms that create contrary to good faith, create a significant imbalance, but the courts have not yet used these rules in a meaningful way for consumers. Most importantly, since Foley v Hill the courts have held customers who deposit money in a bank account lose any rights of property by default: they apparently have only contractual claims in debt for the money to be repaid. If customers did have property rights in their deposits, they would be able to claim their money back upon a bank's insolvency, trace the money if it had been wrongly paid away, and (subject to agreement) claim profits made on the money. However, the courts have denied that bank customers have property rights. The same position has generally spread in banking practice globally, and Parliament has not yet taken the opportunity to ensure banks offer accounts where customer money is protected as property. Because insolvent banks do not, governments have found it necessary to publicly guarantee depositors' savings. This follows the model, started in the Great Depression, the US set up the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, to prevent bank runs. In 2017, the UK guaranteed deposits up to £85,000, mirroring an EU-wide minimum guarantee of €100,000. Moreover, because of the knock-on consequences of any bank failure, because bank debts are locked into a network of international finance, government has found it practically necessary to prevent banks going insolvent. Under the Banking Act 2009 if a bank is going into insolvency, the government may (and usually will if "the stability of the financial systems" is at stake) pursue one of three "stabilisation options". The Bank of England will either try to ensure the failed bank is sold onto another private sector purchaser, set up a subsidiary company to run the failing bank's assets (a "bridge-bank"), or for the UK Treasury to directly take shares in "temporary public ownership". This will wipe out the shareholders, but will keep creditors' claims intact. One method to prevent bank insolvencies, following the "Basel III" programme of the international banker group, has been to require banks hold more money in reserve based on how risky their lending is. EU-wide rules in the Capital Requirements Regulation 2013 achieve this in some detail, for instance requiring proportionally less in reserves if sound government debt is held, but more if mortgage-backed securities are held.

Gas, oil and coal

Further information: Oil and gas industry in the UK, Coal mining in the UK, Mining in the UK, Mining in Cornwall and Devon, Shale gas in the UK, and Fracking in the UK| Gas, oil and coal sources | |

|---|---|

| Energy Act 2016 ss 1-85 and Schs 1-2 | |

| Continental Shelf Act 1964 s 1(1) | |

| Bocardo SA v Star Energy UK Onshore Ltd UKSC 35 | |

| Hydrocarbons Directive 94/22/EC arts 2-6 | |

| Hydrocarbons Licensing Directive Regulations 1995 regs 3-5 | |

| Petroleum Act 1998 ss 1-4 | |

| Petroleum Licensing (Production) (Seaward Areas) Regulations 2008 | |

| R (Frack Free Balcombe) v West Sussex CC EWHC 4108 | |

| Petroleum Act 1998 ss 17-17H | |

| Energy Act 2011 ss 82-83 | |

| Oil Taxation Act 1975 s 1 | |

| Corporation Tax Act 2010 ss 272-279A | |

| Corporation Tax Act 2010 s 330 | |

| Petroleum Act 1998 ss 28A-45 | |

| See UK enterprise law |

Coal, oil and gas remain part of the UK's energy sources, despite the pollution and climate damage they cause. Before the industrial revolution, timber was the main source of energy and heating. After James Watt's steam engine was patented in 1775, and rail transport developed, coal became the UK's dominant energy source. In the 20th century, with the internal combustion engine, oil and gas displaced coal. In the 21st century, because of critical threat of climate damage, wind, hydro, and solar power, and batteries, are replacing gas, oil and coal. In 2015, the UK's energy consumption was 47% petroleum, 29% natural gas, 18% electricity and 5% other. The Climate Change Act 2008 requires the UK government to reduce carbon emissions to zero by 2050. A difficulty is that the Kyoto Protocol measures countries' production, rather than final consumption, and fails to account for the UK's consuming greenhouse gas intensive products that are imported from countries with lower standards, unless there is a border carbon tax, as the EU has introduced.

Although both coal and oil production were publicly owned in the past, coal, oil and gas extraction is performed today by private corporations under government licence. The largest entities include BP, Shell, but also now joined by entirely foreign firms such as Apache, Talisman, CNR, TAQA or Cuadrilla. This means that ordinary UK company law (or US corporate law) sets the governance rights of oil and gas corporations, with board of directors invariably removable only by shareholders (typically large asset managers). Under the Petroleum Act 1998 section 2, rights of land ownership do not equate to rights to oil and gas (or hydrocarbons) underneath. In Bocardo SA v Star Energy UK Onshore Ltd, the Supreme Court did hold that a landowner may sue a company for trespass if it drills under its land without permission, but a majority held that damages will be nominal. This meant that a landowner in Surrey was only able to recover £1,000 when a licensed oil company drilled a diagonal well 800 to 2,800 feet under its property, and not the £621,180 awarded by the High Court to reflect a share of the oil profits. Similarly, under the Continental Shelf Act 1964 section 1 rights "outside territorial waters with respect to the sea bed and subsoil and their natural resources" are "vested in Her Majesty." Since 1919, the Crown has prohibited searching and boring for oil and gas without a licence. Under the Energy Act 2016, licensing is managed by the Oil and Gas Authority (OGA). Under section 8, the OGA should hand out licences so as to minimise future public expense, secure the energy supply, ensure storage of carbon dioxide, fully collaborate with the UK government, encourage innovation, and encourage stable regulation to promote investment. Overshadowing this is the duty in Petroleum Act 1998 sections 9A-I on the Secretary of State for ‘maximising the economic recovery of UK petroleum’, inserted in 2015. This contrasts with the goal of eliminating greenhouse gas emissions in section 1 of the Climate Change Act 2008. The Secretary of State may give directions to the OGA in the interests of national security, or the public in exceptional circumstances, while the OGA is nominally capable of funding itself through fees on licence applicants and holders. In the process of licensing, the Hydrocarbons Licensing Directive Regulations 1995 require objective, transparent and competitive criteria to be applied by the Oil and Gas Authority. Under regulation 3, the OGA should consider an applicant's technical and financial capability, price, previous conduct, and refuse all applications if none are satisfactory, while regulation 5 requires that all criteria to be applied are stated in the public notice for tenders. Under section 4 of the Petroleum Act 1998, model licence clauses are prescribed by the Secretary of State, for instance in the Petroleum Licensing (Production) (Seaward Areas) Regulations 2008. Schedule 1's model clauses give the OGA discretion over the licence term, the licensee's obligation to submit its work programme, revocation on breach of a licence, arbitration for disputes, or health and environmental safety. For onshore oil and gas extraction, and particularly hydraulic fracturing (or "fracking"), there are further requirements that must be fulfilled. For fracking, these include negotiating with landowners where a drill site is situated, getting the local mineral planning authority's approval for exploratory wells, consent from the council under the Town and Country Planning Act 1990 section 57, getting permission for disposing of hazardous waste and inordinate water use, and finally consent from the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy. In R (Frack Free Balcombe Residents Association) v West Sussex CC a residents association in Balcombe lost an action for judicial review of their council's planning permission for Cuadrilla Resources to explore the potential to frack for shale gas. Large protests had opposed any steps toward fracking. However, Gilbart J held that the council had not been wrong in refusing to consider public opposition, and took the view would have acted unlawfully if it had considered the opposition.

The interests of third parties and the public are partially represented through provisions on access to infrastructure, tax, and decommissioning. Under the Petroleum Act 1998 sections 17-17H there is a right of companies that are not owners of pipelines or gas interconnectors to use the infrastructure if there is spare capacity. This is not well used, and it usually left to commercial negotiation. Under the Energy Act 2011 sections 82–83 the Secretary of State can require a pipeline owner gives access on its own motion, apparently to reduce the problem of companies being too timid to exercise legal rights for fear of commercial repercussions. Taxation on oil and gas outputs have increasingly been reduced. Initially, the Oil Taxation Act 1975 section 1 required a special Petroleum Revenue Tax, set as high as 75% of profits in 1983, but this ended for new licences after 1993, and then reduced from 50% in 2010, down to 0% in 2016. Under the Corporation Tax Act 2010 sections 272-279A there is still a "ring-fenced corporation tax", on individual fields that are ring-fenced from other activities, set at 30%, but just 19% for smaller fields. An additional "supplementary charge" of 10% of profits was introduced in 2002 to ensure a ‘fair return’ to the state, because ‘oil companies generating excess profits’. Finally, under the Petroleum Act 1998 sections 29–45 require responsible decommissioning of oil and gas infrastructure. Under section 29, the Secretary of State can require a written notice of a decommissioning plan, on which stakeholders (e.g. the local community) must be consulted. Under section 30, notice regarding abandonment can be served on anyone who owns or has an interest in an installation. There are fines and offences for failure to comply. Estimates for the cost of decommissioning the UK's offshore platforms have been £16.9bn in the next decade, and £75bn to £100bn in total. A series of objections have been raised against the government's policy of cutting taxes while subsidising BP, Shell and Exxon for these costs.

Electricity and energy

See also: UK energy policy, UK solar power, UK wind power, UK nuclear power, UK renewable energy, Energy efficiency in British housing, UK energy, and UK geothermal power| Energy law sources | |

|---|---|

| Climate Change Act 2008 s 1 | |

| Renewable Energy Directive 2009 art 3 and Annex I | |

| Electricity Act 1989 s 32 | |

| Energy Act 2013 ss 1, 6-26, 131 | |

| PreussenElektra AG v Schleswag AG (2001) C-379/98 | |

| Solar Century Ltd v SS for Energy & Climate EWCA Civ 117 | |

| TFEU arts 63 and 345 | |

| Netherlands v Essent (2013) C‑105/12 | |

| Utilities Act 2000 ss 1, 5, 68 and Sch 1 | |

| Electricity Act 1989 ss 3A-10O, 16-23, 32-47, Sch 6 | |

| Trump Golf Club Ltd v Scotland UKSC 74 | |

| R (Gerber) v Wiltshire Council EWCA Civ 84 | |

| Gas Act 1986 ss 3, 4AA, 5-11, 19, 23-23G, 34 | |

| Foster v British Gas plc (1990) C-188/89 | |

| Nuclear Installations Act 1965 ss 1, 65-87 | |

| Insolvency Act 1986 ss 72C-D and Sch 2A, para 10 | |

| Energy Act 2011 ss 94-102 | |

| Standard Electricity Supply Licence, conditions 7-10 | |

| See UK enterprise law |

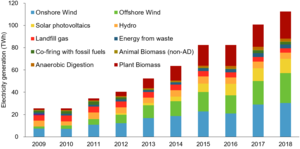

The need for clean energy, and to end climate damage, has driven UK energy policy. The Climate Change Act 2008 section 1 requires a net 100% reduction on 1990 greenhouse gas emissions by 2050, but this can always be made more stringent in line with science or international law. Eliminating carbon emissions and fossil fuels means using only electricity (no more petrol or gas) and only using zero carbon inputs. In 2015, total UK energy use was composed of 18% electricity, 29% natural gas, and 49% petroleum. Electricity itself, by 2015, was generated 24% from "renewable" sources, 30% gas, 22% coal, and 21% nuclear. "Renewable" sources were 48% wind, 9% solar (doubling each year to 2016, but then stagnating), and 7.5% hydroelectric. But 35% of "renewable" electricity was "bioenergy", that is mostly timber, emitting more carbon than coal as it is burnt by converted coal stations. Under the Energy Act 2013 section 1, the Secretary of State can set legally binding decarbonisation targets in electricity. Under section 131, the Secretary of State should give Parliament an annual "Strategy and Policy Statement" on its strategic energy priorities, and how they will be achieved.

Two main strategies have pushed a transition to renewable power. First, under the Electricity Act 1989 sections 32-32M, the Secretary of State was able to place renewables obligations on energy generating companies. Large electricity generating companies (i.e. the big six, British Gas, EDF, E.ON, nPower, Scottish Power and SSE) had to buy fixed percentages of "Renewable Obligation Certificates" from renewable generators if they did not meet set quotas in their own electricity generators. This encouraged significant investment in wind and solar farms, although the Energy Act 2013 enabled the scheme to be closed to new installations over 5 MW capacity in 2015 and all in 2017. In Solar Century Holdings Ltd v SS for Energy and Climate Change a group of solar companies challenged the closure decision by judicial review. Solar Century Ltd claimed they had a legitimate expectation from the government in its previous policy documents for "maintaining support levels". The Court of Appeal rejected the claim, because no unconditional promise was given. As a replacement, under the Energy Act 2013 sections 6–26 created a "contracts for difference" system to subsidise energy companies' investment in renewables. The government owned "Low Carbon Contracts Co." pays licensed energy generators money under contracts lasting, for example, 15 years, reflecting the difference between a predicted future price of electricity (a "reference price") and a predicted future price of electricity with more renewable investment (a "strike price"). The LCCC gets its money from a levy on the energy companies, which pass costs onto consumers. This system was apparently seen by the government as preferable to direct investment by taxing polluters' profits. The second strategy to boost renewables was the Energy Act 2008's "feed-in tariff". Electricity produced with renewables has to be paid a certain price by electricity companies: a "generation" rate (even if the producer uses the energy itself) and an "export" rate (when the producer sells to the grid). In PreussenElektra AG v Schleswag AG a large energy company (now part of E.ON) challenged a similar scheme in Germany. It argued that the feed-in tariff operated like a tax to subsidise renewable energy companies, since non-renewable energy companies passed the costs on, and so should be considered an unlawful state aid, contrary to TFEU article 107. The Court of Justice rejected the argument, holding that the redistributive effects were inherent in the scheme, as indeed they are in any change to private law. Since then, feed-in tariffs have been considerably successful at promoting small scale electricity production by homes and business, and solar and wind in general.

The ownership and governance voice of stakeholders in UK energy companies has been mostly monopolised by private shareholders since the Electricity Act 1989 started the privatisation of the Central Electricity Generating Board. However, in 2015 Robin Hood Energy run by Nottingham City Council, and Bristol Energy run by Bristol City Council became the first new municipally owned energy companies, selling below profit-making company prices and committing to renewable sources. This follows widespread publicly owned energy models around Europe, which the Court of Justice of the European Union held could not be challenged. Under the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union article 345 states the EU treaties "shall in no way prejudice the rules in Member States governing the system of property ownership." Nevertheless, in Netherlands v Essent NV a private Dutch energy company, Essent NV, argued that a Dutch law requiring public ownership of all shares in electricity distribution companies violated free movement of capital in TFEU article 63, as in other cases restrictions on golden shares had been struck down. But the CJEU held nothing precluded either nationalisation or privatisation. It is up to member states alone, and the Dutch government had shown "overriding reasons in the public interest" for public ownership. Given the international evidence that publicly owned energy companies are cheaper, there has been an increase Europe-wide of "remunicipalisation" of services. Many local councils also require both employee and citizen representation in their energy companies. For example, the "Communal Ordinance of North Rhine-Westphalia" (which includes cities like Dortmund) §§107–114 gives councils capacity to create energy companies. If they do, one third of board members will ordinarily be employee representatives, and the constitution must be written to include council representatives, although there are not yet provisions requiring direct voting rights for residents. The Office of Gas and Electricity Markets, or Ofgem, carries out licensing for electricity generation. Its chair and at least two other board members must be appointed by the Secretary of State for 5 to 7 years, and while ostensibly "independent", they must follow directions of the Minister. Under the Electricity Act 1989 nobody can generate and supply electricity to others without a licence. Ofgem follows a Standard Electricity Supply Licence, which can be modified by the Secretary of State if circumstances change, for instance, to alter price controls. There are exemptions from getting a licence, for instance, for small generators under 10 MW (or up to 50 MW if net capacity is under 100 MW), or certain offshore generators. Planning permission for non-exempt generators also require Secretary of State consent, and the granting of planning could be challenged. In Trump International Golf Club Scotland Ltd v The Scottish Ministers Donald Trump, who had recently started his US Presidential campaign argued that the offshore Aberdeen Bay Wind Farm could not be built near his golf course. He argued the Secretary of State could only give permission to existing licensees or exempt generators, ostensibly, by necessary implication from another provision on natural beauty. The Supreme Court unanimously held that Trump lost: there was to be no implied term. In R (Gerber) v Wiltshire Council, Mr Gerber attempted to challenge the construction of a 22 hectare solar farm near his grade II listed home Gifford Hall, because he thought it would have a "detrimental impact" on the "setting". He had not noticed anything happening until some time after construction began, and then tried to argue that Wiltshire Council's "Statement of Community Involvement" required that he would have been notified about the plans he missed. The Court of Appeal unanimously rejected that any "legitimate expectation" in judicial review had been broken.

Unless citizens set up their own generation, or own energy companies through their council, they are guaranteed few other rights by law: the idea has been that Ofgem "protect the interests of consumers" by "promoting effective competition" is meant to automatically improve service. In practice, further duties have been seen as necessary. The Electricity Act 1989 section 44 Ofgem can direct the maximum prices at which electricity may be sold. Originally, the idea was that the regulator would "wither away" as effective market competition replaced any need for a state, but in a transition period prices would be capped through a formula known as "RPI – X". This was supposed to mean that energy companies could only raise their prices by the increase in the retail price index (RPI), minus a percentage calculated by Ofgem to reflect how much in efficiency savings (X) could be made, but also potentially allowing higher prices for investment. Further minimal consumer rights are inserted into the Standard Electricity Supply Licences given to electricity companies. For example, under condition 27, a consumer cannot be disconnected unless all reasonable steps have been taken to let them pay bills (including a pay as you go meter), and pensioners may not be disconnected at all in the winter. This has not, however, come close to eliminating the extra deaths from cold weather (estimated to be around 9000 people in 2016) from fuel poverty. Analogous regulatory regimes for electricity apply to gas, and to nuclear power. In practice there has been no possibility to abolish government involvement, and in law there has been consistent recognition that whether owned by private shareholders or not, energy remains a public service that is the responsibility of the state. When energy companies go into insolvency, often indebted to the government (but not always), they can be put into administrative receivership allowing that creditor greater control over the insolvency process. Under the Standard Electricity Supply Licence, condition 8, Ofgem can impose a duty on energy companies to be a supplier of last resort. These rules were updated slightly in 2011 so that the government can give financial support and keep a company trading until refinancing or a new owner is found.

Water

| Water law sources | |

|---|---|

| Climate Change Act 2008 s 1 | |

| Water Industry Act 1991 ss 2, 11-17 | |

| Water Act 2003 s 52 | |

| Water Industry Act 1991 ss 27A-30 | |

| Water Industry Act 1991 ss 37, 61(1A) and Sch 4A | |

| Water Industry Act 1991 ss 142-143 | |

| R (Oldham MBC) v DG of Water Services (1998) 31 HLR 224 | |

| Water Supply and Sewerage Services (Customer Service Standards) Regulations 2008 | |

| Drinking Water Directive 1998 1998/83/EC | |

| Commission v Spain (2003) C-278/01 | |

| Dept of Transport v North West Water Authority AC 336 | |

| Cambridge Water Ltd v East Counties Leather plc 2 AC 264 | |

| R v Anglian Water Services Ltd EWCA Crim 2243 | |

| Marcic v Thames Water plc UKHL 66 | |

| Manchester Ship Canal Co Ltd v United Utilities Water Plc UKSC 40 | |

| See UK enterprise law |

Water is a universal human right, and basic to survival. While the UK has the fortune of substantial rainfall, climate damage means water resources are under pressure, and less predictable than before. Historically, water for drinking, general use, or sewerage was largely left to private arrangements. The recurrence of water poisoning, and large public health crises were a part of people's ordinary existence until scientific advances of the 19th century. After the Broad Street cholera outbreak of 1854, John Snow first identified the cause of cholera as drinking water being polluted by excrement. Following the Great Stink of 1858, where the River Thames had become so bad smelling that it offended the Queen and forced Parliament to relocate, Joseph Bazalgette began to build the London sewerage system. Starting with the Public Health Act 1848 (11 & 12 Vict. c. 63) and its creation of a local board of health in each council, and the Public Health Act 1866, local government built drains, sewers, and began piping clean water to households. The Waterworks Clauses Act 1847 and 1863 provided model constitutions for the dozens of spreading private and local government water companies. The Public Health Act 1875 required all new houses to have running water and internal drainage. By 1944, there were over 1000 water suppliers in England and Wales, though 26 supplied half, and 97 a further quarter of total volume. The Water Act 1945 organised a national water supply policy, before the Water Act 1973 finally organised ten regional water authorities for England and Wales, and additional authorities in Scotland and Northern Ireland. However, following other privatisations, the Water Act 1989 changed the ten authorities into ten private water companies, each with a local monopoly, subject to price caps of a new regulator known as Ofwat. Scottish Water, after a public campaign remained publicly owned, and as a result has maintained significantly lower prices than in England and Wales. Only around 10 per cent of water companies around the world are privatised, tending to be less efficient and more expensive.

The publicly owned Scottish Water is appointed by Scottish ministers, and overseen by the Water Industry Commission for Scotland, although it has no direct voting power for customers. By contrast, in England and Wales, each company board is typically accountable to shareholders, mostly asset managers, under the Companies Act 2006. While both UK and EU law is clear that water companies, even if privatised, still are public bodies, these companies pursue shareholder profit, only restricted by regulation. Ofwat (technically called the Water Services Regulation Authority) has at least three members appointed the Secretary of State, and is meant to "protect the interests of consumers, wherever appropriate by promoting effective competition" and yet ensure companies have a "reasonable returns on their capital", rather than simply act in the public interest. Ofwat licences companies (known as water "undertakers") to operate water and sewer services with "instruments of appointment", and can impose various conditions. Licences usually last 25 years but can be terminated on 10 years notice by government. Because of public outcry over rising prices, the government tried to construct more competition, with the Water Act 2014 requiring suppliers can access or pump water through other providers' pipes, for a reasonable cost, so that consumers might choose their company. In Scotland, it was thought this kind of competition could pose a public health risk.

As real competition in natural monopolies always appeared unlikely, Ofwat has always set upper limits to prices, historically for 5-year periods. This has followed the formula of RPI – X + K, where prices should rise no more than the retail price index of inflation, reduced by efficiency savings (X), but allowing for capital investment (K). This means prices could be fixed down or go up. Companies must publicise an annual charging scheme approved by Ofwat, while Ofwat must openly report its work programme, report to the Secretary of State, keep a register of appointments and make information on costs available. Companies can appeal to the Competition and Markets Authority for disputes over access and price caps, while Ofwat can refer companies to the CMA for breaches of conditions. After unacceptable experience of people being disconnected by private companies for non-payment, new regulations introduced exemptions for vulnerable customers, particularly people who are unable to pay, have large families or have medical conditions. Everyone has the right to be connect to a water supply and to sewers, but the cost of new connections is borne by the customer. UK water quality is generally high, since large new investments were made following the EU Drinking Water Quality Directive 1998, requiring water is "wholesome and clean". Ofwat is required to issue enforcement orders under the Water Industry Act 1991 section 18 to uphold drinking quality standards, rather than being content with "undertakings" from water companies. The Drinking Water Inspectorate has powers of investigation. There are further standards for water companies to keep up water pressure in pipes, respond quickly to letters, phone calls and keep appointments, restore supply and provide water in emergencies, and stop sewer flooding or compensate up to £1000. Finally, the Consumer Council for Water is meant to hear complaints and publicise issues with Ofwat and water companies, but its members are not elected by water customers and it has no legal power to bind Ofwat or the companies.

Water companies have a chequered history of responsibility for damage they cause, but also the law has failed to ensure businesses are fully responsible for water pollution. In principle, a water authority used to be strictly liable for damage it caused. However, more recently water company liability particularly for sewerage leaks has not appeared to as a sufficient deterrent. In R v Anglian Water Services Ltd the Court of Appeal held that fines for pollution should always be set to ensure sufficient deterrence, but on the facts reduced a fine from £200,000 to £60,000. In Marcic v Thames Water plc the House of Lords held that Thames Water plc was not liable in nuisance, or for breach of a homeowner's right to property, as sewerage repeatedly overflowed residents' gardens. According to Lord Hoffmann, the owners had to use statutory mechanisms to secure accountability rather than suing in tort. More recently in Manchester Ship Canal Co Ltd v United Utilities Water Plc the Supreme Court held that United Utilities was responsible for trespass and pollution of canalways, but only before 1991 when statutory reform provided immunity. By contrast, in Cambridge Water Co Ltd v Eastern Counties Leather plc, the House of Lords held that a tanner business was not liable for polluting the Cambridge Water supply with toxic chemicals, because it said the loss was not "reasonably foreseeable" and therefore too remote. These cases sit uneasily with the principle that polluters should pay, and the scheme of the Water Framework Directive 2000 to ensure proper enforcement of clean water standards.

Agriculture and forestry

Main articles: Agriculture in the UK, Forestry in the UK, Conservation in the UK, and EU law

The UK is made up of around 72% farmland, and 13% woodland, and while agriculture and forestry compose a small percentage of the UK economy and workforce, its regulation has a large impact on the environment. The Common Agricultural Policy in European Union law regulated farming subsidies and development, and remains an influential part of the scheme in the Agriculture Act 2020. This enables the Secretary of State, and the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs to give out financial assistance, make regulations on conditions attached to subsidies, and monitor actions for subsidies. From 2024, this may depart from the standard practice under the EU subsidy scheme of making (1) basic payments to famers based on the number of hectares actively farmed, (2) market measures to buy up and dispose of any excess produce, and (3) rural development payments for a range of spending, such as on clean energy or faster internet infrastructure. Around £3.5 billion was spent in 2018 under the CAP, although the UK government stated that this sums of money would change under the new system, based on a concept of "public money for public goods", but without much clarity.

Around 10% of UK land is held in the public sector, and the largest body among these is the Forestry Commission. The Forestry Act 1967 (c. 10) requires that the Forestry Commission has 11 members appointed by the government, and it has a general duty of "promoting the interests of forestry, the development of afforestation and the production and supply of timber and other forest products" including "adequate reserves of growing trees". National parks were created by the National Parks and Access to the Countryside Act 1949 for the first time, and today are overseen by Natural England or different park authorities under the National Parks (Scotland) Act 2000. Unlike other countries, UK national parks have substantial private ownership, but there are more restrictive planning laws to safeguard natural beauty, and guarantee public rights of way. General protection of the UK's environment is found in the Environmental Protection Act 1990 and Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981.

Housing and building

See also: Right to housing, Landlord–tenant law, Council house, Rent regulation, Affordability of housing in the United Kingdom, and Affordable housing

Although homeowners together own just 5% of the land area in England and Wales, housing and other buildings account for a large share of capital wealth, and constitute the basis of the universal human "right to housing" and to a private life and home. Increasingly homes and real estate have become investment objects, with tax breaks for "Real Estate Investment Trusts", meaning reduced public and individual home ownership. A growing proportion of people cannot afford to buy homes, and so must rent, while rents take a growing share of people's income. Although housing benefit is available for people on low incomes, this is entirely taken by private landlords whose escalating rents are an increasing cost to taxpayers. Since the Housing Act 1985 there has been a right to buy property for secure tenants from local councils that had aimed to keep rents affordable. Despite increased supply and the building of houses at a consistently faster rate than population growth, the greater number of multiple houses owned by landlords and corporations, and units left empty, means that the unequal bargaining power of landlords can be used to charge ever higher rents. The Building Act 1984 and Building Regulations 2010 require reduced carbon in buildings, however there is not yet a requirement for all homes to have solar panels, battery storage, and heat pumps to ensure clean air.

Reflecting its poor housing quality, the UK has among the most minimal tenant rights in the world. Fair rent regulation exists in many countries to prevent unaffordable housing, such as in Canada, or Germany, but was abolished in the UK by the Housing Act 1985 section 24. The Landlord and Tenant Act 1985 contains the right to know who the landlord it, that it is habitable, and that the landlord carries out basic repairs to the building and facility structure. However there is no housing regulator or watchdog to which tenants may apply, and so their rights have to be enforced through costly court processes. The Housing Act 1988 section 20 abolished security for tenants against eviction without good reasons (unless there is something in the contract), and so upon a contractual notice period tenants may be removed. The only statutory protection is a minimum of 4 weeks notice before eviction in the Protection from Eviction Act 1977 section 5(1), and the landlord may issue a section 21 notice under the Housing Act 1988 section 21 to being a court process of eviction. The Tenant Fees Act 2019 sections 1-5 contain minimal regulation of real estate agent fees, requiring that they are only charged to landlords, not tenants. The Housing Act 2004 sections 213-214 create a right for a rental deposit to be protected under a trust of a third party, however these parties are often appointed and paid by the landlord, meaning that in disputes that are arbitrated the landlord usually wins. By contrast, business tenancies have much more regulation, recognising the inherently unequal bargaining power that tenants have, and the failure of the market. On top of rents, and mortgage repayments for landowners, people must pay council tax and business rates to contribute to the locality for their property. Stamp duty in the United Kingdom is a tax that has to be paid upon the sale of property, and Inheritance Tax (United Kingdom) of 40% must be paid upon the passing to children or grandchildren of property worth over £500,000 in 2023, or £325,000 to other parties, but no tax for leaving a property to a spouse, civil partner or charity.

Transport

| Rail sources | |

|---|---|

| Railways and Transport Safety Act 2003 ss 15-16, Sch 1 | |

| Railways Act 1993 ss 4-23 and 25 | |

| Single European Railway Directive 2012/34/EU | |

| Great North Eastern Railway Ltd v ORR EWHC 1942 | |

| Tamlin v Hannaford 1 KB 18 | |

| Greater London Authority Act 1999 ss 210-231 | |

| R (TfL) v London Regional Transport EWHC Admin 637 | |

| R (HS2 Action Alliance Ltd) v SS for Transport UKSC 3 | |

| Rail Passenger Rights Regulation 2007 arts 3-29 | |

| R (Save Our Railways) v Director of Rail CLC 596 | |

| Railways Act 2005 ss 19-21 and Schs 5-6 | |

| Railways Act 1993 ss 76-78 | |

| Railways Act 1993 ss 28-29 and GLAA 1999 s 174 | |

| Bromley LBC v Greater London Council UKHL 7 | |

| Railways Act 1993 ss 59-65 and Sch 6 (insolvency) | |

| Greater London Authority Act 1999 ss 220-224 and Schs 14-15 | |

| Winsor v Administrators of Railtrack Plc EWCA Civ 955 | |

| Weir v Secretary of State for Transport EWHC 2192 (Ch) | |

| Re Metronet Rail BCV Ltd EWHC 2697 (Ch) | |

| see UK enterprise law |

As the home of the industrial revolution, and a densely populated country, the UK's transport networks are among the world's oldest and most used. Roman roads in Britain are still major thoroughfares. From medieval times, highways were maintained through turnpike trusts, a system of parish and toll funded roads. While the British Empire developed as a maritime power abroad, canals were built in the early industrial revolution to transport large volumes of goods. With steam engine technology, railway construction spread, and then boomed from 1840. Private investors built railways with huge subsidies from Parliament, granting planning and compulsory purchase rights, and were only haphazardly held responsible in tort law for worker deaths, and damage to the environment. Under the Transport Act 1947, the government nationalised British Rail. Yet in the post-war period, more people were encouraged to buy cars, and more goods transportation shifted into trucking. Commercial aviation also developed rapidly. British Rail was privatised once more after the Railways Act 1993 was put into effect in 1996, as again more people switched away from over-crowded roads to trains. The need to eliminate fossil fuels in accordance with the Climate Change Act 2008 means more trains have been electrified, and electric motor vehicles are slowly being introduced.

Since 2015, the Office of Rail and Road has been a combined regulator for railways and highways. The chair and four other members is appointed by the Secretary of State for up to five-year terms, and can be dismissed for a good reason. Although it exercises no direct control, under the Railways Act 1993 section 4 the ORR has a long list of duties, including to improve railway service performance in the interest of passengers, promote usage, "competition", interconnection, safety, but also to enable railways companies "to plan the future of their businesses with a reasonable degree of assurance."

The Single European Railway Directive 2012 requires that infrastructure managers and "railway undertakings" are structurally separate, so that railway companies (whether public or privately owned) have less of an incentive to exclude other operators. Each must have separate accounts and member states are obliged to run railways "at the lowest possible cost for the quality of service required", although in practice this enables huge variety and ownership structures around different countries. In the UK, infrastructure is managed by Network Rail. It was originally privatised and called Railtrack, and was meant to run as a regulated monopoly, in private hands, and be in charge of railway tracks, signalling, tunnels, bridges, level crossings. However, after the Hatfield train crash in 2000 which killed 4 people and injured 70, and the Potters Bar crash in 2001 which killed 7 and injured 76, it was forced into insolvent administration and the government took rail infrastructure back into public ownership. In Weir v Secretary of State for Transport a group of 48,000 shareholders challenged the Minister's decision to force an insolvency procedure, arguing their property was being illegally taken and the Minister was guilty of "misfeasance" in public office, but these were completely rejected. Network Rail, from 2003, became a not-for-profit company, re-investing in safety, and is accountable to the Office of Rail and Road.

New infrastructure projects will require planning permission, and environmental impact consultation. In R (HS2 Action Alliance Ltd) v SS for Transport a group of people opposed to the High Speed Rail 2 project argued it failed the consultation standards in the Environmental Impact Assessment Directive 2011, because there was a party whipped vote in Parliament for its approval. The Supreme Court rejected the claim, because political organisation did not stop proper consultation and debate.