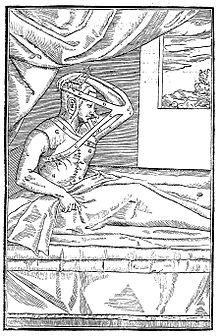

Engraving from De Curtorum Chirurgia per Insitionem "(On the Surgery of Mutilation by Grafting)" (1597) by Gaspare Tagliacozzi Engraving from De Curtorum Chirurgia per Insitionem "(On the Surgery of Mutilation by Grafting)" (1597) by Gaspare Tagliacozzi | |

| Occupation | |

|---|---|

| Names |

|

| Occupation type | Specialty |

| Activity sectors | Medicine, surgery |

| Description | |

| Education required |

|

| Fields of employment | Hospitals, clinics |

Plastic surgery is a surgical specialty involving the restoration, reconstruction, or alteration of the human body. It can be divided into two main categories: reconstructive surgery and cosmetic surgery. Reconstructive surgery covers a wide range of specialties, including craniofacial surgery, hand surgery, microsurgery, and the treatment of burns. This category of surgery focuses on restoring a body part or improving its function. In contrast, cosmetic (or aesthetic) surgery focuses solely on improving the physical appearance of the body. A comprehensive definition of plastic surgery has never been established, because it has no distinct anatomical object and thus overlaps with practically all other surgical specialties. An essential feature of plastic surgery is that it involves the treatment of conditions that require or may require tissue relocation skills.

Etymology

The word plastic in plastic surgery is in reference to the concept of "reshaping" and comes from the Greek πλαστική (τέχνη), plastikē (tekhnē), "the art of modelling" of malleable flesh. This meaning in English is seen as early as 1598. In the surgical context, the word "plastic" first appeared in 1816 and was established in 1838 by Eduard Zeis, preceding the modern technical usage of the word as "engineering material made from petroleum" by 70 years.

History

See also: History of surgery

Treatments for the plastic repair of a broken nose are first mentioned in the c. 1600 BC Egyptian medical text called the Edwin Smith papyrus. The early trauma surgery textbook was named after the American Egyptologist, Edwin Smith. Reconstructive surgery techniques were being carried out in India by 800 BC. Sushruta was a physician who made contributions to the field of plastic and cataract surgery in the 6th century BC.

The Romans also performed plastic cosmetic surgery, using simple techniques, such as repairing damaged ears, from around the 1st century BC. For religious reasons, they did not dissect either human beings or animals, thus, their knowledge was based in its entirety on the texts of their Greek predecessors. Notwithstanding, Aulus Cornelius Celsus left some accurate anatomical descriptions, some of which—for instance, his studies on the genitalia and the skeleton—are of special interest to plastic surgery.

Several ancient Sanskrit medical treatise mentions some types of plastic surgery in India such as the works of Sushruta and Charaka. These works were translated into the Arabic language during the Abbasid Caliphate in 750 AD. The Arabic translations made their way into Europe via intermediaries. In Italy, the Branca family of Sicily and Gaspare Tagliacozzi (Bologna) became familiar with the techniques of Sushruta.

All fields of surgery, the Arab physician, surgeon, and chemist Al-Zahrawi talks of the use of silk thread suture to achieve good cosmesis. He describes what is thought to be the first attempt at reduction mammaplasty for the management of gynaecomastia. He gives detailed descriptions of other basic surgical techniques such as cautery and wound management.

| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Plastic surgery" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (July 2024) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

British physicians travelled to India to see rhinoplasties being performed by Indian methods. Reports on Indian rhinoplasty performed by a Kumhar (potter) vaidya were published in the Gentleman's Magazine by 1794. Joseph Constantine Carpue spent 20 years in India studying local plastic surgery methods. Carpue was able to perform the first major surgery in the Western world in the year 1815. Instruments described in the Sushruta Samhita were further modified in the Western world.

In 1465, Sabuncu's book, description, and classification of hypospadias were more informative and up to date. Localization of the urethral meatus was described in detail. Sabuncuoglu also detailed the description and classification of ambiguous genitalia. In mid-15th-century Europe, Heinrich von Pfolspeundt described a process "to make a new nose for one who lacks it entirely, and the dogs have devoured it" by removing skin from the back of the arm and suturing it in place. However, because of the dangers associated with surgery in any form, especially that involving the head or face, it was not until the 19th and 20th centuries that such surgery became common.

In 1814, Joseph Carpue successfully performed an operative procedure on a British military officer who had lost his nose to the toxic effects of mercury treatments. In 1818, German surgeon Carl Ferdinand von Graefe published his major work entitled Rhinoplastik. Von Graefe modified the Italian method using a free skin graft from the arm instead of the original delayed pedicle flap.

The first American plastic surgeon was John Peter Mettauer, who, in 1827, performed the first cleft palate operation with instruments that he designed himself.

Johann Friedrich Dieffenbach specialized in skin transplantation and early plastic surgery. His work in rhinoplastic and maxillofacial surgery established many modern techniques of reconstructive surgery. In 1845, Dieffenbach wrote a comprehensive text on rhinoplasty, titled Operative Chirurgie, and introduced the concept of reoperation to improve the cosmetic appearance of the reconstructed nose. Dieffenbach has been called the "father of plastic surgery".

Another case of plastic surgery for nose reconstruction from 1884 at Bellevue Hospital was described in Scientific American.

In 1891, American otorhinolaryngologist John Roe presented an example of his work: a young woman on whom he reduced a dorsal nasal hump for cosmetic indications. In 1892, Robert Weir experimented unsuccessfully with xenografts (duck sternum) in the reconstruction of sunken noses. In 1896, James Israel, a urological surgeon from Germany, and in 1889 George Monks of the United States each described the successful use of heterogeneous free-bone grafting to reconstruct saddle nose defects. In 1898, Jacques Joseph, the German orthopaedic-trained surgeon, published his first account of reduction rhinoplasty. In 1910, Alexander Ostroumov, the Russian pharmacist, and perfume and cosmetics manufacturer, founded a unique plastic surgery department in his Moscow Institute of Medical Cosmetics. In 1928, Jacques Joseph published Nasenplastik und Sonstige Gesichtsplastik.

Nascency of maxillofacial surgery

| This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (May 2023) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

The development of weapons such as machine guns and explosive shells during World War I created trench warfare, which led to a rapid increase in the number of mutilations to the faces and the heads of soldiers because the trenches mainly offered protection to the body. The surgeons, who were not prepared for these injuries, were even less prepared for a large number of injuries and had to react quickly and intelligently to treat the greatest number. Facial injuries were hard to treat on the front line and, because of the sanitary conditions, many infections could occur. Sometimes, some stitches were made on a jagged wound without considering the amount of flesh that had been lost, so the resulting scars were hideous and disfigured soldiers. Some of the wounded had severe injuries and the stitches were not sufficient so some became blind, or were left with gaping holes instead of their nose. Harold Gillies, scared by the number of new facial injuries and the lack of good surgical techniques, decided to dedicate an entire hospital to the reconstruction of facial injuries as fully as possible. He took into account the psychological dimension. Gillies introduced skin grafts to the treatments of soldiers, so they would be less horrified by looking at themselves in the mirror.

It is the multidisciplinary approach to the treatment of facial lesions, bringing together plastic surgeons, dental surgeons, technicians, and specialized nurses, which has made it possible to develop techniques leading to the reconstruction of injured faces. Gillies identified the need to advance the specialty of maxillofacial surgery which would be directly dedicated to the management of war wounds at this time. He developed a new technique using rotational and transposition flaps but also bone grafts from the ribs and tibia to reconstruct facial defects caused by the weapons during the war. Gillies experimented with this technique so he knew that he had to start by moving back healthy tissue to its normal position and then he would be able to fill with tissue from another place on the body of the soldier. One of the most successful techniques in skin grafting had the aim of not completely severing the connection to the body. It was possible by releasing and lifting a flap of skin from the wound. The flap of skin, still connected to the donor site, would then be swung over the site of the wound, allowing the maintenance of physical connection and ensuring that blood is supplied to the skin, increasing the chances of the skin graft being accepted by the body. At this time, we assisted also to improving in treating infections also meant that important injuries had become survivable mostly thanks to the new technique of Gillies. Some soldiers arrived at the hospital of Gillies without noses, chins, cheekbones, or even eyes. But for them, the most important trauma was psychological.

Development of modern techniques

| This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (February 2024) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

The father of modern plastic surgery is generally considered to have been Sir Harold Gillies. A New Zealand otolaryngologist working in London, he developed many of the techniques of modern facial surgery in caring for soldiers with disfiguring facial injuries during the First World War.

During World War I, he worked as a medical minder with the Royal Army Medical Corps. After working with the French oral and maxillofacial surgeon Hippolyte Morestin on skin grafts, he persuaded the army's chief surgeon, Arbuthnot-Lane, to establish a facial injury ward at the Cambridge Military Hospital, Aldershot, later upgraded to a new hospital for facial repairs at Sidcup in 1917. There Gillies and his colleagues developed many techniques of plastic surgery; more than 11,000 operations were performed on more than 5,000 men (mostly soldiers with facial injuries, usually from gunshot wounds). After the war, Gillies developed a private practice with Rainsford Mowlem, including many famous patients, and travelled extensively to promote his advanced techniques worldwide.

In 1930, Gillies' cousin, Archibald McIndoe, joined the practice and became committed to plastic surgery. When World War II broke out, plastic surgery provision was largely divided between the different services of the armed forces, and Gillies and his team were split up. Gillies himself was sent to Rooksdown House near Basingstoke, which became the principal army plastic surgery unit; Tommy Kilner (who had worked with Gillies during the First World War, and who now has a surgical instrument named after him, the kilner cheek retractor) went to Queen Mary's Hospital, Roehampton; and Mowlem went to St Albans. McIndoe, consultant to the RAF, moved to the recently rebuilt Queen Victoria Hospital in East Grinstead, Sussex, and founded a Centre for Plastic and Jaw Surgery. There, he treated very deep burns, and serious facial disfigurement, such as loss of eyelids, typical of those caused to aircrew by burning fuel.

McIndoe is often recognized for not only developing new techniques for treating badly burned faces and hands but also for recognising the importance of the rehabilitation of the casualties and particularly of social reintegration back into normal life. He disposed of the "convalescent uniforms" and let the patients use their service uniforms instead. With the help of two friends, Neville and Elaine Blond, he also convinced the locals to support the patients and invite them to their homes. McIndoe kept referring to them as "his boys" and the staff called him "The Boss" or "The Maestro".

His other important work included the development of the walking-stalk skin graft, and the discovery that immersion in saline promoted healing as well as improving survival rates for patients with extensive burns—this was a serendipitous discovery drawn from observation of differential healing rates in pilots who had come down on land and in the sea. His radical, experimental treatments led to the formation of the Guinea Pig Club at Queen Victoria Hospital, Sussex. Among the better-known members of his "club" were Richard Hillary, Bill Foxley and Jimmy Edwards.

Sub-specialties

| It has been suggested that portions of Cosmetic_surgery_in_Australia#Types of cosmetic surgery available be split from it and merged into this article. (Discuss) (April 2020) |

| This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (February 2024) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Plastic surgery is a broad field, and may be subdivided further. In the United States, plastic surgeons are board certified by American Board of Plastic Surgery. Subdisciplines of plastic surgery may include:

Aesthetic surgery

Aesthetic surgery is a central component of plastic surgery and includes facial and body aesthetic surgery. Plastic surgeons use cosmetic surgical principles in all reconstructive surgical procedures as well as isolated operations to improve overall appearance.

Burn surgery

Burn surgery generally takes place in two phases. Acute burn surgery is the treatment immediately after a burn. Reconstructive burn surgery takes place after the burn wounds have healed.

Craniofacial surgery

Main article: Craniofacial surgeryCraniofacial surgery is divided into pediatric and adult craniofacial surgery. Pediatric craniofacial surgery mostly revolves around the treatment of congenital anomalies of the craniofacial skeleton and soft tissues, such as cleft lip and palate, microtia, craniosynostosis, and pediatric fractures. Adult craniofacial surgery deals mostly with reconstructive surgeries after trauma or cancer and revision surgeries along with orthognathic surgery and facial feminization surgery. Craniofacial surgery is an important part of all plastic surgery training programs. Further training and subspecialisation is obtained via a craniofacial fellowship. Craniofacial surgery is also practiced by maxillofacial surgeons.

Ethnic plastic surgery

Main article: Ethnic plastic surgeryEthnic plastic surgery is plastic surgery performed to change ethnic attributes, often considered used as a way of "passing".

Hand surgery

Main article: Hand surgeryHand surgery is concerned with acute injuries and chronic diseases of the hand and wrist, correction of congenital malformations of the upper extremities, and peripheral nerve problems (such as brachial plexus injuries or carpal tunnel syndrome). Hand surgery is an important part of training in plastic surgery, as well as microsurgery, which is necessary to replant an amputated extremity. The hand surgery field is also practiced by orthopedic surgeons and general surgeons. Scar tissue formation after surgery can be problematic on the delicate hand, causing loss of dexterity and digit function if severe enough. There have been cases of surgery on women's hands in order to correct perceived flaws to create the perfect engagement ring photo.

Microsurgery

Main article: MicrosurgeryMicrosurgery is generally concerned with the reconstruction of missing tissues by transferring a piece of tissue to the reconstruction site and reconnecting blood vessels. Popular subspecialty areas are breast reconstruction, head and neck reconstruction, hand surgery/replantation, and brachial plexus surgery.

Pediatric plastic surgery

Main article: Pediatric plastic surgeryChildren often face medical issues very different from the experiences of an adult patient. Many birth defects or syndromes present at birth are best treated in childhood, and pediatric plastic surgeons specialize in treating these conditions in children. Conditions commonly treated by pediatric plastic surgeons include craniofacial anomalies, Syndactyly (webbing of the fingers and toes), Polydactyly (excess fingers and toes at birth), cleft lip and palate, and congenital hand deformities.

Prison plastic surgery

Main article: Prison plastic surgeryPlastic surgery performed on an incarcerated population in order to affect their recidivism rate, a practice instituted in the early 20th century that lasted until the mid-1990s. Separate from surgery performed for medical need.

Techniques and procedures

In plastic surgery, the transfer of skin tissue (skin grafting) is a very common procedure. Skin grafts can be derived from the recipient or donors:

- Autografts are taken from the recipient. If absent or deficient of natural tissue, alternatives can be cultured sheets of epithelial cells in vitro or synthetic compounds, such as integra, which consists of silicone and bovine tendon collagen with glycosaminoglycans.

- Allografts are taken from a donor of the same species. Kidney transplants are an example of allograft transfer. Joseph Murray is credited for completing the first successful kidney transplantation in 1954.

- Xenografts are taken from a donor of a different species.

Usually, good results would be expected from plastic surgery that emphasize careful planning of incisions so that they fall within the line of natural skin folds or lines, appropriate choice of wound closure, use of best available suture materials, and early removal of exposed sutures so that the wound is held closed by buried sutures.

Cosmetic surgery procedures

Cosmetic surgery is a voluntary or elective surgery that is performed on normal parts of the body with the only purpose of improving a person's appearance or removing signs of aging. Some cosmetic surgeries such as breast reduction are also functional and can help to relieve symptoms of discomfort such as back ache or neck ache. Cosmetic surgeries are also undertaken following breast cancer and mastectomy to recreate the natural breast shape which has been lost during the process of removing the cancer. In 2014, nearly 16 million cosmetic procedures were performed in the United States alone. The number of cosmetic procedures performed in the United States has almost doubled since the start of the century. 92% of cosmetic procedures were performed on women in 2014, up from 88% in 2001. 15.6 million cosmetic procedures were performed in 2020, with the five most common surgeries being rhinoplasties, blepharoplasties, rhytidectomies, liposuctions, and breast augmentation. Breast augmentation continues to be one of the top 5 cosmetic surgical procedures and has been since 2006. Silicone implants were used in 84% and saline implants in 16% of all breast augmentations in 2020. The American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery looked at the statistics for 34 different cosmetic procedures. Nineteen of the procedures were surgical, such as rhinoplasties or rhytidectomies. The nonsurgical procedures included botox and laser hair removal. In 2010, their survey revealed that there were 9,336,814 total procedures in the United States. Of those, 1,622,290 procedures were surgical (p. 5). They also found that a large majority, 81%, of the procedures were done on Caucasian people (p. 12).

In 1949, 15,000 Americans underwent cosmetic surgery procedures and by 1969 this number rose to almost half a million people. The American Society of Plastic Surgeons estimates that more than 333,000 cosmetic procedures were performed on patients 18 years of age or younger in the US in 2005 compared to approx. 14,000 in 1996. In 2018, more than 226,994 patients between the ages of 13 and 19 underwent plastic surgery compared to just over 218,900 patients in the same age group in 2010. Concerns about young people undergoing plastic surgery include the financial burden of additional surgical procedures needed to correct problems after the initial cosmetic surgery, long-term health complications from plastic surgery, and unaddressed mental health issues that may have led to surgery. The increased use of cosmetic procedures crosses racial and ethnic lines in the U.S., with increases seen among African-Americans, Asian Americans and Hispanic Americans as well as Caucasian Americans. In Asia, cosmetic surgery has become more popular, and countries such as China and India have become Asia's biggest cosmetic surgery markets. South Korea is also rising in popularity in Asian and Western countries due to their expertise in facial bone surgeries (see cosmetic surgery in South Korea).

Plastic surgery is increasing slowly, rising 115% from 2000 to 2015. "According to the annual plastic surgery procedural statistics, there were 15.9 million surgical and minimally-invasive cosmetic procedures performed in the United States in 2015, a 2 percent increase over 2014." A study from 2021 found that requests for cosmetic procedures had increased significantly since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, possibly due to the increase in videoconferencing; cited estimates include a 10% increase in the United States and a 20% increase in France.

The most popular aesthetic/cosmetic procedures include:

- Abdominoplasty ("tummy tuck"): reshaping and firming of the abdomen

- Blepharoplasty ("eyelid surgery"): reshaping of upper/lower eyelids including Asian blepharoplasty

- Phalloplasty ("penile surgery"): construction (or reconstruction) of a penis or, sometimes, artificial modification of the penis by surgery, often for cosmetic purposes

- Mammoplasty:

- Breast augmentations ("breast implant" or "boob job"): augmentation of the breasts by means of fat grafting, saline, or silicone gel prosthetics, which was initially performed for women with micromastia

- Reduction mammoplasty ("breast reduction"): removal of skin and glandular tissue, which is done to reduce back and shoulder pain in women with gigantomastia and for men with gynecomastia

- Mastopexy ("breast lift"): Lifting or reshaping of breasts to make them less saggy, often after weight loss (after a pregnancy, for example). It involves removal of breast skin as opposed to glandular tissue

- Augmentation mastopexy ("breast lift with breast implants"): Lifting breasts to make them less saggy, repositioning the nipple to a higher location, and increasing breast size with saline or silicone gel implants. Recent studies of a newer technique for simultaneous augmentation mastopexy (SAM) indicate that it is a safe surgical procedure with minimal medical complications. The SAM technique involves invaginating and tacking the tissues first, in order to previsualize the result, before making any surgical incisions to the breast.

- Buttock augmentation ("butt implant"): enhancement of the buttocks using silicone implants or fat grafting ("Brazilian butt lift") where fat is transferred from other areas of the body

- Cryolipolysis: refers to a medical device used to destroy fat cells. Its principle relies on controlled cooling for non-invasive local reduction of fat deposits to reshape body contours.

- Cryoneuromodulation: Treatment of superficial and subcutaneous tissue structures using gaseous nitrous oxide, including temporary wrinkle reduction, temporary pain reduction, treatment of dermatologic conditions, and focal cryo-treatment of tissue

- Calf augmentation: done by silicone implants or fat transfer to add bulk to calf muscles

- Labiaplasty: surgical reduction and reshaping of the labia

- Lip augmentation: alter the appearance of the lips by increasing their fullness through surgical enlargement with lip implants or nonsurgical enhancement with injectable fillers

- Cheiloplasty: surgical reconstruction of the lip

- Rhinoplasty ("nose job"): reshaping of the nose sometimes used to correct breathing impaired by structural defects.

- Otoplasty ("ear surgery"/"ear pinning"): reshaping of the ear, most often done by pinning the protruding ear closer to the head.

- Rhytidectomy ("face lift"): removal of wrinkles and signs of aging from the face

- Neck lift: tightening of lax tissues in the neck. This procedure is often combined with a facelift for lower face rejuvenation.

- Browplasty ("brow lift" or "forehead lift"): elevates eyebrows, smooths forehead skin

- Midface lift ("cheek lift"): tightening of the cheeks

- Genioplasty: augmentation of the chin with an individual's bones or with the use of an implant, usually silicone, by suture of the soft tissue

- Mentoplasty: surgery to the chin. This can involve either enhancing or reducing the size of the chin. Enhancements are achieved with the use of facial implants. Reduction of the chin involved reducing the size of the chin bone.

- Cheek augmentation ("cheek implant"): implants to the cheek

- Orthognathic surgery: altering the upper and lower jaw bones (through osteotomy) to correct jaw alignment issues and correct the teeth alignment

- Fillers injections: collagen, fat, and other tissue filler injections, such as hyaluronic acid

- Brachioplasty ("Arm lift"): reducing excess skin and fat between the underarm and the elbow

- Laser skin rejuvenation or laser resurfacing: the lessening of depth of facial pores and exfoliation of dead or damaged skin cells

- Liposuction ("suction lipectomy"): removal of fat deposits by traditional suction technique or ultrasonic energy to aid fat removal

- Zygoma reduction plasty: reducing the facial width by performing osteotomy and resecting part of the zygomatic bone and arch

- Jaw reduction: reduction of the mandible angle to smooth out an angular jaw and creating a slim jaw

- Buccal fat extraction: extraction of the buccal pads

- Body contouring: the removal of this excess skin and fat from numerous areas of the body, restoring the appearance of skin elasticity of the remaining skin. The surgery is prominent in those who have undergone significant weight loss resulting in excess sagging skin being present around areas of the body. The skin loses elasticity (a condition called elastosis) once it has been stretched past capacity and is unable to recoil back to its standard position against the body and also with age.

- Sclerotherapy: removing visible 'spider veins' (Telangiectasia), which appear on the surface of the skin.

- Dermal fillers: Dermal fillers are injected below the skin to give a more fuller, youthful appearance of a feature or section of the face. One type of dermal filler is Hyaluronic acid. Hyaluronic acid is naturally found throughout the human body. It plays a vital role in moving nutrients to the cells of the skin from the blood. It is also commonly used in patients with arthritis as it acts like a cushion to the bones which have depleted the articular cartilage casing. Development within this field has occurred over time with synthetic forms of hyaluronic acid is being created, playing roles in other forms of cosmetic surgery such as facial augmentation.

- Micropigmentation: is the creation of permanent makeup using natural pigments to places such as the eyes to create the effect of eye shadow, lips creating lipstick and cheek bones to create a blush like look. The pigment is inserted beneath the skin using a machine which injects a small needle at a very fast rate carrying pigment into the skin, creating a lasting colouration of the desired area.

In 2015, the most popular surgeries were botox, liposuction, blepharoplasties, breast implants, rhynoplasties, and rhytidectomies. According to the 2020 Plastic Surgery Statistics Report, which is published by the American Society of Plastic Surgeons, the most surgical procedure performed in the U.S. was rhinoplasty (nose reshaping) accounting for 15.2% of all cosmetic surgical procedures that year, followed by blepharoplasty (eyelid surgery), which accounted for 14% of all procedures. The third most populous procedure was rhytidectomy (facelift) (10% of all procedures), then liposuction (9.1% of all procedures).

Complications, risks, and reversals

All surgery has risks. Common complications of cosmetic surgery includes hematoma, nerve injury, infection, scarring, implant failure and end organ damage. Breast implants can have many complications, including rupture. In a study of his 4761 augmentation mammaplasty patients, Eisenberg reported that overfilling saline breast implants 10–13% significantly reduced the rupture-deflation rate to 1.83% at 8-years post-implantation. In 2011 FDA stated that one in five patients who received implants for breast augmentation will need them removed within 10 years of implantation.

Psychological disorders

Although media and advertising do play a large role in influencing many people's lives, such as by making people believe plastic surgery to be an acceptable course to change one's identity to their liking, researchers believe that plastic surgery obsession is linked to psychological disorders such as body dysmorphic disorder. There exists a correlation between those with BDD and the predilection toward cosmetic plastic surgery in order to correct a perceived defect in their appearance.

BDD is a disorder resulting in the individual becoming "preoccupied with what they regard as defects in their bodies or faces". Alternatively, where there is a slight physical anomaly, then the person's concern is markedly excessive. While 2% of people have body dysmorphic disorder in the United States, 15% of patients seeing a dermatologist and cosmetic surgeons have the disorder. Half of the patients with the disorder who have cosmetic surgery performed are not pleased with the aesthetic outcome. BDD can lead to suicide in some people with the condition. While many with BDD seek cosmetic surgery, the procedures do not treat BDD, and can ultimately worsen the problem. The psychological root of the problem is usually unidentified; therefore causing the treatment to be even more difficult. Some say that the fixation or obsession with correction of the area could be a sub-disorder such as anorexia or muscle dysmorphia. The increased use of body and facial reshaping applications such as Snapchat and Facetune have been identified as potential triggers of BDD. Recently, a phenomenon referred to as 'Snapchat dysmorphia' has appeared to describe people who request surgery to resemble the edited version of themselves as they appear through Snapchat filters. In response to the detrimental trend, Instagram banned all augmented reality (AR) filters that depict or promote cosmetic surgery.

In some cases, people whose physicians refuse to perform any further surgeries, have turned to "do it yourself" plastic surgery, injecting themselves and facing extreme safety risks.

See also

- Biomaterial

- Body modification

- Cosmetic surgery in Australia

- Dental trauma

- Dermatologic surgical procedure

- Ethnic plastic surgery

- List of plastic surgery flaps

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Scalp reconstruction

- Serdev suture

- Rejuvenation

References

- "What is Cosmetic Surgery". Royal College of Surgeons. Retrieved 15 January 2013.

- "Plastic Surgery Specialty Description". American Medical Association. Retrieved 13 July 2020.

- Oxford English Dictionary, s.v. 'plastic'

- "plastic surgery". OED Online. Britannica. Retrieved 12 February 2015.

- Zeis, Eduard (1838). Handbuch der plastischen Chirurgie (in German). Berlin: Reimer.

- "Plastic". Etymonline. Retrieved 2 March 2014.

- "Academy Papyrus to be Exhibited at the Metropolitan Museum of Art". The New York Academy of Medicine. 27 July 2005. "The New York Academy of Medicine: News & Publications: Academy Papyrus to be Exhibited at the Metropolitan Museum of Art". Archived from the original on 27 November 2010. Retrieved 12 August 2008.. Retrieved 2008-08-12.

- Shiffman M (5 September 2012). Cosmetic Surgery: Art and Techniques. Springer. p. 20. ISBN 978-3-642-21837-8.

- ^ Holland, Oscar (30 May 2021). "From ancient Egypt to Beverly Hills: A brief history of plastic surgery". CNN. Retrieved 3 October 2021.

- MSN Encarta (2008). Plastic Surgery Archived 22 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- Dwivedi, Girish & Dwivedi, Shridhar (2007). History of Medicine: Sushruta – the Clinician – Teacher par Excellence Archived 10 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine. National Informatics Centre (Government of India).

- Atiyeh, Bishara; Habal, Mutaz B. (4 May 2023). "Forgotten Pioneers of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery During the Medieval Period". Journal of Craniofacial Surgery. 34 (3): 1144–1146. doi:10.1097/SCS.0000000000009176. ISSN 1049-2275. PMID 36727967.

- Wolfgang H. Vogel, Andreas Berke (2009). "Brief History of Vision and Ocular Medicine". Kugler Publications. p.97. ISBN 90-6299-220-X

- P. Santoni-Rugiu, A History of Plastic Surgery (2007)

- ^ Lock, Stephen etc. (200ĞďéĠĊ1). The Oxford Illustrated Companion to Medicine. US: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-262950-6. (page 607)

- Maniglia AJ (August 1989). "Reconstructive rhinoplasty". The Laryngoscope. 99 (8 Pt 1): 865–7. doi:10.1288/00005537-198908000-00017. PMID 2666806. S2CID 5730172.

- Ahmad, Z. (2007). "Sh08Al-Zahrawi – the Father of Surgery". ANZ Journal of Surgery. 77. doi:10.1111/j.1445-2197.2007.04130_8.x. S2CID 57308997.

- ^ Lock, Stephen etc. (2001). The Oxford Illustrated Companion to Medicine. US: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-262950-6. (page 651)

- Mukherjee, Nayana Sharma; Majudar, Susmita Basu; Majumdar, Susmita Basu (2011). "A Nose Lost and Honour Regained: The Indian Method of Rhinoplasty Revisited". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 72: 968–977. ISSN 2249-1937. JSTOR 44146788.

- ^ Lock, Stephen etc. (2001). The Oxford Illustrated Companion to Medicine. US: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-262950-6. (page 652)

- "Plastic Surgery".

- "MedWay". MedWay.

- Scientific American. Munn & Company. 7 June 1884. p. 354.

- Stochik, A. A (2020). "Bulletin of Semashko National Research Institute of Public Health, The first large-scale productions of parfumes and cosmetics in Russia and the establishment of The Institute of Medical Cosmetics by pharmacist A. M. Ostroumov, Part I". №1 (2020) (1). The National Research Institute of Public Health, Moskow: 76–79. doi:10.25742/NRIPH.2020.01.0013.

- Bhattacharya S (October 2008). "Jacques Joseph: Father of modern aesthetic surgery". Indian Journal of Plastic Surgery. 41 (Suppl): S3 – S8. PMC 2825133. PMID 20174541.

- Alotaibi A, Aljabab A, Althubaiti G (November 2018). "Predictors of Oral Function and Facial Aesthetics Post Maxillofacial Reconstruction with Free Fibula Flap". Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. Global Open. 6 (11): e1787. doi:10.1097/GOX.0000000000001787. PMC 6414127. PMID 30881773.

- Stathopoulos P (March 2018). "Maxillofacial surgery: the impact of the Great War on both sides of the trenches". Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 22 (1): 21–24. doi:10.1007/s10006-017-0659-5. PMID 29067543. S2CID 3418182.

- "The birth of plastic surgery | National Army Museum". www.nam.ac.uk. Retrieved 15 December 2022.

- Klein C (26 October 2018). "Innovative Cosmetic Surgery Restored WWI Vets' Ravaged Faces—And Lives". HISTORY. Retrieved 15 December 2022.

- Zola M (May 2004). "World War I maxillofacial fracture splints". Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 62 (5): 643. doi:10.1016/j.joms.2004.02.005. PMID 15141677.

- Chambers JA, Ray PD (November 2009). "Achieving growth and excellence in medicine: the case history of armed conflict and modern reconstructive surgery". Annals of Plastic Surgery. 63 (5): 473–8. doi:10.1097/SAP.0b013e3181bc327a. PMID 20431512.

- Roxburgh, Tracey (11 April 2017). "Pupil speeches honour soldiers". Otago Daily Times Online News. Retrieved 14 September 2024.

- Mowbrey, K. (2013). "Albert Ross Tilley: The legacy of a Canadian plastic surgeon". The Canadian Journal of Plastic Surgery. 21 (2): 102–106. doi:10.1177/229255031302100202. PMC 3891087. PMID 24431953.

- Furness, Hannah (21 May 2017). "Story of maverick WW2 'Guinea pig' surgeon to be told on big screen for first time". The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 14 September 2024.

- Kennedy, Maev (4 April 2013). "War surgeon Sir Archibald McIndoe and his 'Guinea Pigs' honoured". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 14 September 2024.

- "Introduction". American Board of Plastic Surgery. 2013. Archived from the original on 2 February 2014. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- Description of Plastic Surgery American Board of Plastic Surgery Archived 15 October 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- "Reconstructive Burn Surgery | University of Michigan Health". www.uofmhealth.org. Retrieved 3 March 2024.

- "Hand Rejuvenation for Better Engagement Ring Selfies". ABC News. Retrieved 12 September 2015.

- Syndactyly at eMedicine

- "Reconstructive Plastic Surgery of the Face" (PDF).

- "Plastic Surgery Statistics Report" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 April 2016. Retrieved 31 March 2016.

- "2001 Cosmetic Surgery Statistics". Retrieved 12 September 2015.

- "2020 Plastic Surgery Statistics Report" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery (2010). "Cosmetic Surgery National Data Bank Statistics". Aesthetic Surgery Journal: 1–18.

- ^ "2018 Cosmetic Surgery Age Distribution" (PDF). American Society of Plastic Surgeons. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 29 August 2022.

- "Plastic Surgery". The New York Times. 27 September 1971. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 25 August 2020.

- "2010 Cosmetic Surgery Age Distribution" (PDF). American Society of Plastic Surgeons. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 29 August 2022.

- Zuckerman D, Abraham A (October 2008). "Teenagers and cosmetic surgery: focus on breast augmentation and liposuction". The Journal of Adolescent Health. 43 (4): 318–24. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.04.018. PMID 18809128.

- India, China Among Plastic Surgery Hot Spots – WebMD

- Facial Bone Contouring Surgery.

- "New Statistics Reflect the Changing Face of Plastic Surgery". 25 February 2015. Retrieved 15 November 2017.

- Padley RH, Di Pace B (April 2021). "Touch-ups, Rejuvenation, Re-dos and Revisions: Remote Communication and Cosmetic Surgery on the Rise". Aesthetic Plastic Surgery. 45 (6): 3078–3080. doi:10.1007/s00266-021-02235-1. PMC 8018227. PMID 33797578.

- "Covid-19 is fuelling a Zoom-boom in cosmetic surgery". The Economist. 11 April 2021. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 18 June 2021.

- Stevens WG, Macias LH, Spring M, Stoker DA, Chacón CO, Eberlin SA (July 2014). "One-Stage Augmentation Mastopexy: A Review of 1192 Simultaneous Breast Augmentation and Mastopexy Procedures in 615 Consecutive Patients". Aesthetic Surgery Journal. 34 (5): 723–732. doi:10.1177/1090820X14531434. PMID 24792479.

- Eisenberg T (April 2012). "Simultaneous augmentation mastopexy: a technique for maximum en bloc skin resection using the inverted-T pattern regardless of implant size, asymmetry, or ptosis". Aesthetic Plastic Surgery. 36 (2): 349–54. doi:10.1007/s00266-011-9796-7. PMID 21853404. S2CID 19402937.

- ^ Park S (2017). Facial bone contouring surgery: a practical guide. Singapore: Springer. ISBN 978-981-10-2726-0. OCLC 1004601615.

- "What is chin surgery?". American Society of Plastic Surgeons.

- Marie K, Thomas MC (2013). "33". Fast Living Slow Ageing: How to age less, look great, live longer, get more (4th ed.). Strawberry Hills, Australia: Health Inform Pty Ltd. pp. 229–311. ISBN 978-0-9806339-2-4.

- "What is body contouring?". American Society of Plastic Surgeons.

- "Spider Vein Treatment". American Society of Plastic Surgeons.

- "What are dermal fillers?". American Society of Plastic Surgeons.

- "The Most Popular Cosmetic Procedures". WebMD. Archived from the original on 10 September 2015. Retrieved 12 September 2015.

- The American Board of Plastic Surgery (2021). "2020 Plastic Surgery Statistics | Cosmetic Procedure Trends" (PDF).

- "Plastic surgery – Complications – NHS Choices". www.nhs.uk. 23 October 2017.

- "Cosmetic surgery Risks – Mayo Clinic". Mayo Clinic.

- Eisenberg T (March 2021). "Does Overfilling Smooth Inflatable Saline-Filled Breast Implants Decrease the Deflation Rate? Experience with 4761 Augmentation Mammaplasty Patients". Aesthetic Plastic Surgery. 45 (5): 1991–1999. doi:10.1007/s00266-021-02198-3. PMC 8481168. PMID 33712871.

- "FDA Update on the Safety of Silicone Gel-Filled Breast Implants". Center for Devices and Radiological Health U.S. Food and Drug Administration. June 2011.

- Elliott A (2011). "'I Want to Look Like That!': Cosmetic Surgery and Celebrity Culture". Cultural Sociology. 5 (4): 463–477. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.1028.8768. doi:10.1177/1749975510391583. S2CID 145370171.

- Ribeiro RV (August 2017). "Prevalence of Body Dysmorphic Disorder in Plastic Surgery and Dermatology Patients: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis". Aesthetic Plastic Surgery. 41 (4): 964–970. doi:10.1007/s00266-017-0869-0. PMID 28411353. S2CID 29619456.

- ^ Veale D (February 2004). "Body dysmorphic disorder". Postgraduate Medical Journal. 80 (940): 67–71. doi:10.1136/pmj.2003.015289. PMC 1742928. PMID 14970291.

- Miller MC (July 2005). "What is body dysmorphic disorder?". The Harvard Mental Health Letter. 22 (1): 8. PMID 16193565.

- "A new reality for beauty standards: How selfies and filters affect body image". EurekAlert! (Press release). Boston Medical Center. Retrieved 4 February 2019.

- "Instagram bans 'cosmetic surgery' filters". BBC News. 23 October 2019.

- Canning A (20 July 2009). "Woman's DIY Plastic Surgery 'Nightmare'". ABC News.

Further reading

- Atkinson M (2008). "Exploring Male Femininity in the 'Crisis': Men and Cosmetic Surgery". Body & Society. 14: 67–87. doi:10.1177/1357034X07087531. S2CID 143604536.

- Fraser S (2003). Cosmetic surgery, gender and culture. Palgrave. ISBN 978-1-4039-1299-2.

- Gilman S (2005). Creating Beauty to Cure the Soul: Race and Psychology in the Shaping of Aesthetic Surgery. Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-2144-6.

- Haiken E (1997). Venus Envy: A History of Cosmetic Surgery. Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-5763-8.

- Kolle FS (1911). Plastic and Cosmetic Surgery. D. Appleton and Company.

- Santoni-Rugiu P (2007). A History of Plastic Surgery. Springer. ISBN 978-3-540-46240-8.

External links

- Countries with the largest total number of cosmetic procedures, Statista, 2019

- Cosmetic Surgery Statistics, American Cosmetic Association, 2023

| Cosmetics | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Face | |||||

| Lips | |||||

| Eyes | |||||

| Hair | |||||

| Nails | |||||

| Body | |||||

| Related | |||||

| |||||