| Red imported fire ant | |

|---|---|

| |

| A group of fire ant workers | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Hymenoptera |

| Family: | Formicidae |

| Subfamily: | Myrmicinae |

| Genus: | Solenopsis |

| Species: | S. invicta |

| Binomial name | |

| Solenopsis invicta Buren, 1972 | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Solenopsis invicta, the fire ant, or red imported fire ant (RIFA), is a species of ant native to South America. A member of the genus Solenopsis in the subfamily Myrmicinae, it was described by Swiss entomologist Felix Santschi as a variant of S. saevissima in 1916. Its current specific name invicta was given to the ant in 1972 as a separate species. However, the variant and species were the same ant, and the name was preserved due to its wide use. Though South American in origin, the red imported fire ant has been accidentally introduced in Australia, New Zealand, several Asian and Caribbean countries, Europe and the United States. The red imported fire ant is polymorphic, as workers appear in different shapes and sizes. The ant's colours are red and somewhat yellowish with a brown or black gaster, but males are completely black. Red imported fire ants are dominant in altered areas and live in a wide variety of habitats. They can be found in rainforests, disturbed areas, deserts, grasslands, alongside roads and buildings, and in electrical equipment. Colonies form large mounds constructed from soil with no visible entrances because foraging tunnels are built and workers emerge far away from the nest.

These ants exhibit a wide variety of behaviours, such as building rafts when they sense that water levels are rising. They also show necrophoric behaviour, where nestmates discard scraps or dead ants on refuse piles outside the nest. Foraging takes place on warm or hot days, although they may remain outside at night. Workers communicate by a series of semiochemicals and pheromones, which are used for recruitment, foraging, and defence. They are omnivores and eat dead mammals, arthropods, insects, seeds, and sweet substances such as honeydew from hemipteran insects with which they have developed relationships. Predators include arachnids, birds, and many insects including other ants, dragonflies, earwigs, and beetles. The ant is a host to parasites and to a number of pathogens, nematodes, and viruses, which have been viewed as potential biological control agents. Nuptial flight occurs during the warm seasons, and the alates may mate for as long as 30 minutes. Colony founding can be done by a single queen or a group of queens, which later contest for dominance once the first workers emerge. Workers can live for several months, while queens can live for years; colony numbers can vary from 100,000 to 250,000 individuals. Two forms of society in the red imported fire ant exist: polygynous colonies (nests with multiple queens) and monogynous colonies (nests with one queen).

Venom plays an important role in the ant's life, as it is used to capture prey or for defence. About 95% of the venom consists of water-insoluble piperidine alkaloids known as solenopsins, with the rest comprising a mixture of toxic proteins that can be particularly potent in sensitive humans; the name fire ant is derived from the burning sensation caused by their sting. More than 14 million people are stung by them in the United States annually, where many are expected to develop allergies to the venom. Most victims experience intense burning and swelling, followed by the formation of sterile pustules, which may remain for several days. However, 0.6% to 6.0% of people may suffer from anaphylaxis, which can be fatal if left untreated. Common symptoms include dizziness, chest pain, nausea, severe sweating, low blood pressure, loss of breath, and slurred speech. More than 80 deaths have been recorded from red imported fire ant attacks. Treatment depends on the symptoms; those who only experience pain and pustule formation require no medical attention, but those who suffer from anaphylaxis are given adrenaline. Whole body extract immunotherapy is used to treat victims and is regarded as highly effective.

The ant is viewed as a notorious pest, causing billions of dollars in damage annually and impacting wildlife. The ants thrive in urban areas, so their presence may deter outdoor activities. Nests can be built under structures such as pavements and foundations, which may cause structural problems, or cause them to collapse. Not only can they damage or destroy structures, but red imported fire ants also can damage equipment and infrastructure and impact business, land, and property values. In agriculture, they can damage crops and machinery, and threaten pastures. They are known to invade a wide variety of crops, and mounds built on farmland may prevent harvesting. They also pose a threat to animals and livestock, capable of inflicting serious injury or killing them, especially young, weak, or sick animals. Despite this, they may be beneficial because they consume common pest insects on crops. Common methods of controlling these ants include baiting and fumigation; other methods may be ineffective or dangerous. Due to its notoriety and importance, the ant has become one of the most studied insects on the planet, even rivalling the western honey bee (Apis mellifera).

Etymology and common names

The specific epithet of the red imported fire ant, invicta, derives from Latin, and means "invincible" or "unconquered". The epithet originates from the phrase Roma invicta ("unconquered Rome"), used as an inspirational quote until the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476 AD. The generic name, Solenopsis, translates as "appearance of a pipe". It is a compound of two Ancient Greek words, solen, meaning "pipe" or "channel", and opsis, meaning "appearance" or "sight". The ant is commonly known as the "red imported fire ant" (abbreviated as RIFA); the "fire ant" part is because of the burning sensation caused by its sting. Alternative names include "fire ant", "red ant" or "tramp ant". In Brazil, locals call the ant toicinhera, which derives from the Portuguese word toicinho (pork fat).

Taxonomy

The red imported fire ant was first described by Swiss entomologist Felix Santschi in a 1916 journal article published by Physis. Originally named Solenopsis saevissima wagneri from a syntype worker collected from Santiago del Estero, Argentina, Santschi believed the ant was a variant of S. saevissima; the specific epithet, wagneri, derives from the surname of E.R. Wagner, who collected the first specimens. The type material is currently housed in Naturhistorisches Museum Basel, Switzerland, but additional type workers are possibly housed in the Muséum national d'histoire naturelle, Paris. In 1930, American myrmecologist William Creighton reviewed the genus Solenopsis and reclassified the taxon as Solenopsis saevissima electra wagneri at infrasubspecific rank, noting that he could not collect any workers that referred to Santschi's original description. In 1952, the S. saevissima species complex was examined and, together with nine other species-group names, S. saevissima electra wagneri was synonymised with S. saevissima saevissima. This reclassification was accepted by Australian entomologist George Ettershank in his revision of the genus and in Walter Kempf's 1972 catalogue of Neotropical ants.

In 1972, American entomologist William Buren described what he thought was a new species, naming it Solenopsis invicta. Buren collected a holotype worker from Cuiabá in Mato Grosso, Brazil, and provided the first official description of the ant in a journal article published by the Georgia Entomological Society. He accidentally misspelled invicta as invica [sic] above the description pages of the species, although it was clear that invicta was the intended spelling because of the constant use of the name in the article. The type material is currently housed in the National Museum of Natural History, Washington, D.C.

In a 1991 review of the species complex, American entomologist James Trager synonymised S. saevissima electra wagneri and S. wagneri together. Trager incorrectly cites Solenopsis saevissima electra wagneri as the original name, erroneously believing that the name S. wagneri was unavailable and used Buren's name S. invicta. Trager previously believed that S. invicta was conspecific with S. saevissima until comparing the material with S. wagneri. Trager notes that though S. wagneri has priority over S. invicta, the name was never used above infrasubspecific rank. The use of the name since Santschi has not been associated with collected specimens, and as a result is nomen nudum. In 1995, English myrmecologist Barry Bolton corrected Trager's error, recognising S. wagneri as the valid name and synonymised S. invicta. He states that Trager wrongfully classified S. wagneri as an unavailable name and cites S. saevissima electra wagneri as the original taxon. He concludes that S. wagneri is, in fact, the original name and has priority over S. invicta.

In 1999, Steve Shattuck and colleagues proposed conserving the name S. invicta. Since the first description of S. invicta, over 1,800 scientific papers using the name were published discussing a wide range of topics about its ecological behaviour, genetics, chemical communication, economic impacts, methods of control, population, and physiology. They state that the use of S. wagneri is a "threat" to nomenclatural stability towards scientists and non-scientists; taxonomists may have been able to adapt to such name change, but name confusion may arise if such case occurred. Due to this, Shattuck and his colleagues proposed the continued use of S. invicta and not S. wagneri, as this name has been rarely used; between 1995 and 1998, over 100 papers were published using S. invicta and only three using S. wagneri. They requested that the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN) use plenary powers to suppress S. wagneri for the purpose of the Principle of Priority and not for the Principle of Homonymy. Furthermore, they requested that the name S. invicta be added to the Official List of Specific Names in Zoology and that S. wagneri be added to the Official Index of Rejected Invalid Specific Names in Zoology. Upon review, the proposal was voted on by the entomological community and was supported by all but two voters. They note that there is no justification in suppressing S. wagneri; instead, it would be better to give precedence to S. invicta over S. wagneri whenever an author treated them as conspecific. The ICZN would conserve S. invicta and suppress S. wagneri in a 2001 review. Under the present classification, the red imported fire ant is a member of the genus Solenopsis in the tribe Solenopsidini, subfamily Myrmicinae. It is a member of the family Formicidae, belonging to the order Hymenoptera, an order of insects containing ants, bees, and wasps.

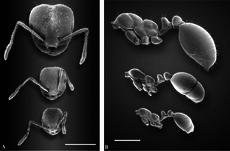

Heads of S. invicta (left) and S. richteri (right). Both ants are similar to each other morphologically and genetically.

Heads of S. invicta (left) and S. richteri (right). Both ants are similar to each other morphologically and genetically.

Phylogeny

The red imported fire ant is a member of the S. saevissima species-group. Members can be distinguished by their two-jointed clubs at the end of the funiculus in workers and queens, and the second and third segments of the funiculus are twice as long and broad in larger workers. Polymorphism occurs in all species and the mandibles bear four teeth. The following cladogram shows the position of the red imported fire ant among other members of the S. saevissima species-group:

| Solenopsis |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Phenotypic and genetic data suggest that the red imported fire ant and the black imported fire ant (Solenopsis richteri) differ from each other, but they do share a close genetic relationship. Hybridisation between the two ants occurs in areas where they make contact, with the hybrid zone located in Mississippi. Such hybridisation has resulted from secondary contact between these two ants several decades ago, when they first encountered each other in southern Alabama. Based on mitochondrial DNA, examined haplotypes do not form a monophyletic clade. Some of the examined haplotypes form a closer relationship to S. megergates, S. quinquecuspis and S. richteri than they do with other S. invicta haplotypes. The occurrence of a possible paraphyletic grouping suggests that the red imported fire ant and S. quinquecuspis are possible cryptic species groups composed of several species that cannot be distinguished morphologically.

Genetics

Studies show that mitochondrial DNA variation occurs substantially in polygyne societies (nests with multiple queens), but no variation is detected in monogyne societies (nests with a single queen). Triploidy (a chromosomal abnormality) occurs in red imported fire ants at high rates (as high as 12% in non-reproductive females), which is linked to the high frequency of diploid males. The red imported fire ant is the first species shown to possess a green-beard gene, by which natural selection can favour altruistic behaviour. Workers containing this gene are able to distinguish between queens containing it, and those that do not, apparently by using odour cues. The workers kill queens that do not contain the gene. In 2011, scientists announced they had fully sequenced the red imported fire ant genome from a male.

Description

Red imported fire ant workers range in size from small to medium, making them polymorphic. Workers measure between 2.4 and 6.0 mm (0.094 and 0.236 in). The head measures 0.66 to 1.41 mm (0.026 to 0.056 in) and is 0.65 to 1.43 mm (0.026 to 0.056 in) wide. In the larger workers (as in the major workers), their heads measure 1.35 to 1.40 mm (0.053 to 0.055 in) and 1.39 to 1.42 mm (0.055 to 0.056 in) wide. The antenna scapes measure 0.96 to 1.02 mm (0.038 to 0.040 in) and the thoracic length is 1.70 to 1.73 mm (0.067 to 0.068 in). The head becomes wider behind the eyes with rounded occipital lobes present, and unlike the similar-looking S. richteri, the lobes peak further than the midline, but the occipital excision is not as crease-like. The scapes in major workers do not extend beyond occipital peak by one or two scape diameters; this feature is more noticeable in S. richteri. In medium-sized workers, the scapes reach the occipital peaks and exceed the rear border in the smallest workers. In small and medium workers, the head tends to have more elliptical sides. The head of small workers is wider out front than it is behind. In the major workers, the pronotum does not have any angular shoulders, nor does it have any sunken posteromedian area. The promesonotum is convex and the propodeum base is rounded and also convex. The base and declivity are of equal length. The suture of the promesonotum is either strong or weak in larger workers. The petiole has a thick and blunt scale; if observed from behind, it is not as rounded above in contrast to S. richteri, and sometimes it may be subtruncate. The postpetiole is large and broad, and in the larger workers, it is broader than its length. The postpetiole tends to be less broad in front and broader behind. On the rear side of the dorsal surface, a transverse impression is present. In S. richteri, this feature is also present but much weaker.

The sculpture is very similar to S. richteri. The punctures are from where pilosity arises, and these are often elongated on the dorsal and ventral portions of the head. On the thorax, striae are present, but they are less engraved with fewer punctures than in S. richteri. On the petiole, the punctates are located on the sides. The postpetiole, when viewed above, has a strong shagreen with distinct transverse punctostriae. The sides are covered in deep punctures, where they appear smaller but deeper. In S. richteri, the punctures are larger and more shallow. This gives a more opaque appearance to the surface. In some cases, punctostriae may be present around the rear portion. The pilosity appears similar to that of S. richteri. These hairs are erect and vary in length, appearing long on each side of the pronotum and mesonotum; on the head, the long hairs are seen in longitudinal rows. Numerous appressed pubescent hairs are on the petiolar scale; this is the opposite in S. richteri, as these hairs are sparse. Workers appear red and somewhat yellowish with a brown or completely black gaster. Gastric spots are sometimes seen in larger workers, where they are not as brightly coloured as those in S. richteri. The gastric spot usually covers a small portion of the first gastric tergite. The thorax is concolorous, ranging from light reddish-brown to dark-brown. The legs and coxae are usually lightly shaded. The head has a consistent colour pattern in large workers, with the occiput and vertex appearing brown. Other parts of the head, including the front, genae, and the central region of the clypeus, are either yellowish or yellowish brown. The anterior borders of the genae and mandibles are dark-brown; they also both appear to share the same coloured shade with the occiput. The scapes and funiculi range from being the same colour as the head or shares the same shade with the occiput. Light-coloured areas of the head in small to medium-sized workers is restricted to only the frontal region, with a dark mark resembling an arrow or rocket being present. On occasion, nests may have a series of different colours. For example, workers may be much darker, and the gastric spot may be completely absent or appear dark-brown.

Queens have a head length of 1.27 to 1.29 mm (0.050 to 0.051 in) and a width of 1.32 to 1.33 mm (0.052 to 0.052 in). The scapes measure 0.95 to 0.98 mm (0.037 to 0.039 in) and the thorax is 2.60 to 2.63 mm (0.102 to 0.104 in). The head is almost indistinguishable from S. richteri, but the occipital excision is less crease-like and the scapes are considerably shorter. Its petiolar scale is convex and resembles that of S. richteri. The postpetiole has straight sides that never concave, unlike in S. richteri where they concave. The thorax is almost identical, but the clear space between the metapleural striate area and propodeal spiracles is either a narrow crease or not present. The side portions of the petiole are punctate. The sides of the postpetiole are opaque with punctures present, but no irregular roughening is seen. The anterior of the dorsum is shagreen, and the middle and rear regions bear transverse puncto-striae. All these regions have erect hairs. The anterior portions of both the petiole and postpetiole have appressed pubescence that is also seen on the propodeum. The colour of the queen is similar to that of a worker: the gaster is dark brown and the legs, scapes, and thorax are light brown with dark streaks on the mesoscutum. The head is yellowish or yellowish-brown around the central regions, the occiput and mandibles are a similar colour to the thorax, and the wing veins range from colourless to pale brown. Males appear similar to S. richteri, but the upper borders of the petiolar scales are more concave. In both species, the postpetiole's and petiole's spiracles strongly project. The whole body of the male is concolorous black, but the antennae are whitish. Like the queen, the wing veins are colourless or pale brown.

The red imported ant can be misidentified as the similar-looking S. richteri. The two species can be distinguished from each other through morphological examinations of the head, thorax, and postpetiole. In S. richteri, the sides of the head are broadly elliptical and the cordate shape seen in the red imported fire ant is absent. The region of the occipital lobes that are situated nearby the midline and occipital excision appear more crease-like in S. richteri than it does in the red imported fire ant. The scapes of S. richteri are longer than they are in the red imported fire ant, and the pronotum has strong angulate shoulders. Such character is almost absent in the red imported fire ant. A shallow but sunken area is only known in the larger workers of S. richteri, which is located in the posterior region of the dorsum of the pronotum. This feature is completely absent in larger red imported fire ant workers. The red imported fire ant's promesonotum is strongly convex, whereas this feature is weakly convex in S. richteri. Upon examination, the base of the propodeum is elongated and straight in S. richteri, while convex and shorter in the red imported fire ant. It also has a wide postpetiole with either straight or diverging sides. The postpetiole in S. richteri is narrower with converging sides. In S. richteri, the transverse impression on the posterodorsal portion of the postpetiole is strong, but weak or absent in the red imported fire ant. As well as that, S. richteri workers are 15% larger than red imported fire ant workers, are blackish-brown, and have a yellow stripe on the dorsal side of the gaster.

Brood

Eggs are tiny and oval-shaped, remaining the same size for around a week. After one week, the egg assumes the shape of an embryo and forms as a larva when the egg shell is removed. Larvae measure 3 mm (0.12 in). They show a similar appearance to S. geminata larvae, but they can be distinguished by the integument with spinules on top of the dorsal portion of the posterior somites. The body hairs measure 0.063 to 0.113 mm (0.0025 to 0.0044 in) with a denticulate tip. The antennae both have two or three sensilla. The labrum is smaller with two hairs on the anterior surface that are 0.013 mm (0.00051 in). The maxilla has a sclerotised band between the cardo and stipes. The labium also has a small sclerotised band. The tubes of the labial glands are known to produce or secrete a proteinaceous substance that has a rich level of digestive enzymes, which includes proteases and amylases that function as an extraintestinal digestion of solid food. The midgut also contains amylases, roteases and upases. The narrow cells in its reservoir have little to no function in secretion. The pupae resemble adults of any caste, except that their legs and antennae are held tightly against the body. They appear white, but over time, the pupa turns darker when they are almost ready to mature.

Four larval instars have been described based on distinctive morphological characters. The larvae of the minor and major workers are impossible to distinguish before the final instar, when size differences become apparent. Upon pupation a wider head width difference between castes become more evident. Reproductive larvae are larger than worker larvae, and present discrete morphological differences in mouthparts. Fourth-instar larvae of males and queens can be differentiated based on their relative shape and body coloration, and also internal gonopodal imaginal discs can differ.

Polymorphism

The red imported fire ant is polymorphic with two different castes of workers: minor workers and major workers (soldiers). Like many ants that exhibit polymorphism, young, smaller ants do not forage and tend to the brood instead, while the larger workers go out and forage. In incipient colonies, polymorphism does not exist, but instead they are occupied by monomorphic workers called "minims" or "nanitics". The average head-width in tested colonies increases during the first six months of development. In five-year-old colonies, the head width of minor workers decreases, but for major workers, the head-width remains the same. The total weight of a major worker is twice that of a minor worker when they first arrive, and by six months, major workers are four times heavier than minor workers. Once major workers develop, they can make up a large portion of the workforce, with as many as 35% being major workers in a single colony. This does not affect colony performance, as polymorphic colonies and nests with small workers produce broods at roughly the same rate, and polymorphism is not an advantage or disadvantage when food sources are not limited. However, polymorphic colonies are more energetically efficient, and under conditions where food is limited, polymorphism may provide a small advantage in brood production, but this depends on the levels of food stress.

As worker ants grow to larger sizes, the shape of the head changes, due to the head length growing at the same time as the total body length, and the head width may grow by 20%. The length of the antennae only grows slowly; the antennae may only grow 60% longer by the time the body doubles its length, thus the relative antennal length decreases by 20% as the length of the body doubles. All individual legs of the body are isometric with body length meaning that even when the length of the body doubles, the legs will also double. However, not all of the legs are the same length; the prothoracic portion accounts for 29% of leg length, the mesothoracic 31%, and the metathoracic 41%. The first two pairs of legs are of equal length to one another, whereas the final pair is longer. Overall, the morphological appearance of a worker changes dramatically when it grows larger. The head exhibits the greatest shape change and the height of the alinotum grows quicker than its length, where a height/length ratio of 0.27 in minor workers and 0.32 in major workers is seen. Due to this, larger workers tend to have a humped-shape and robust alinotum in contrast to smaller workers. No petiole segment exhibits any change in shape as the size of the body changes. The width of the gaster grows more rapidly than its length, where the width may be 96% of its length but increases to 106%.

Physiology

Like other insects, the red imported fire ant breathes through a system of gas-filled tubes called tracheae connected to the external environment through spiracles. The terminal tracheal branches (tracheoles) make direct contact with internal organs and tissue. The transport of oxygen to cells (and carbon dioxide out of cells) occurs through diffusion of gases between the tracheoles and the surrounding tissue and is assisted by a discontinuous gas exchange. As with other insects, the direct communication between the tracheal system and tissues eliminates the need for a circulating fluid network to transport O2. Thus, red imported fire ants and other arthropods can have a modest circulatory system though they have highly expensive metabolic demands.

The excretory system consists of three regions. The basal region has three cells found within the posterior portion of the midgut. The anterior and superior cavities are formed by the bases of four Malpighian tubules. The superior cavity opens into the lumen of the small intestine. The rectum is a large but thin-walled sac that occupies the posterior fifth of the larvae. The release of waste is controlled by the rectal valves that lead to the anus. Sometimes, the larvae secrete a liquid that consists of uric acid, water and salts. These contents are often carried outside by workers and ejected, but colonies under water stress may consume the contents. In the reproductive system, queens release a pheromone that prevents dealation and oogenesis in virgin females; those tested in colonies without a queen begin oocyte development after dealation and take up the egg-laying role. Flight muscle degeneration is initiated by mating and juvenile hormones, and prevented by corpus allatectomy. Histolysis begins with the dissolution of the myofibril and the slow breakdown of the myofilaments. Such dissolution continues until it reaches the only free Z-line materials, which would also disappear; only the nuclei and lamellar bodies remain. In one study, the amino acids increase in the hemolymph after insemination.

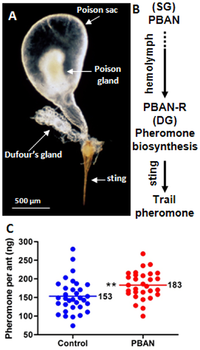

The glandular system contains four glands: the mandibular, maxillary, labial, and postpharyngeal glands. The postpharyngeal is well developed in the queen, while the other glands are larger in workers. The postpharyngeal gland functions as a vacuum to absorb fatty acids and triglycerides, as well as a gastric caecum. The functions of the other glands remain poorly understood. In one study discussing the enzymes of the digestion system of adult ants, lipase activity was found in the mandibular and labial glands, as well as invertase activity. The Dufour's gland found in the ant acts as a source of trail pheromones, although scientists believed the poison gland was the source of the queen pheromone. The neurohormone pheromone biosynthesis activating neuropeptide is found in the ant that activates the biosynthesis of pheromones from the Dufour's gland. The spermatheca gland is found in queens, which functions in sperm maintenance. Males appear to lack these glands, but those associated with its head are morphologically similar to those found in workers, but these glands may act differently.

The ant faces many respiratory challenges due to its highly variable environment, which can cause increased desiccation, hypoxia, and hypercapnia. Hot, humid climates cause an increase in heart rate and respiration which increases energy and water loss. Hypoxia and hypercapnia can result from red imported fire ant colonies living in poorly ventilated thermoregulatory mounds and underground nests. Discontinuous gas exchange (DGE) may allow ants to survive the hypercapnic and hypoxic conditions frequently found in their burrows; it is ideal for adapting to these conditions because it allows the ants to increase the period of O2 intake and CO2 expulsion independently through spiracle manipulation. The invasion success of the red imported fire ant may possibly be related to its physiological tolerance to abiotic stress, being more heat tolerant and more adaptable to desiccation stress than S. richteri. This means that the ant is less vulnerable to heat and desiccation stress. Although S. richteri has higher water body content than the red imported fire ant, S. richteri was more vulnerable to desiccation stress. The lower sensitivity to desiccation is due to a lower water loss rate. Colonies living in unshaded and warmer sites tend to have a higher heat tolerance than those living in shaded and cooler sites.

Metabolic rate, which indirectly affects respiration, is also influenced by environmental temperature. Peak metabolism occurs at about 32 °C. Metabolism, and therefore respiration rate, increases consistently as temperature increases. DGE stops above 25 °C, although the reason for this is currently unknown.

Respiration rate also appears to be influenced significantly by caste. Males show a considerably higher rate of respiration than females and workers, due, in part, to their capability for flight and higher muscle mass. In general, males have more muscle and less fat, resulting in a higher metabolic O2 demand. While the metabolic rate is highest at 32 °C, colonies often thrive at slightly cooler temperatures (around 25 °C). The high rate of metabolic activity associated with warmer temperatures is a limiting factor on colony growth because the need for food consumption is also increased. As a result, larger colonies tend to be found in cooler conditions because the metabolic demands required to sustain a colony are decreased.

Distribution and habitat

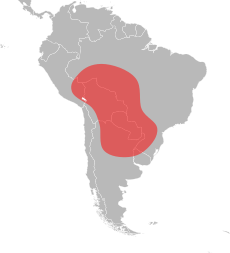

Red imported fire ants are native to the tropical areas of central South America, where they have an expansive geographical range that extends from southeastern Peru to central Argentina, and to the south of Brazil. In contrast to its geographical range in North America, its range in South America is significantly different. It has an extremely long north–south range, but a very narrow east–west distribution. The northernmost record of the red imported fire ant is Porto Velho in Brazil, and its southernmost record is Resistencia in Argentina; this is a distance of about 3,000 km (1,900 mi). In comparison, the width of its narrow range is about 350 km (220 mi), and this is most likely narrower into southern Argentina and Paraguay and into the northern areas of the Amazon River basin. Most known records of the red imported fire ant are around the Pantanal region of Brazil. However, the interior of this area has not been examined thoroughly, but it is certain that the species occurs in favourable locations around it. The Pantanal region is thought to be the original homeland of the red imported fire ant; hydrochore dispersal via floating ant rafts could easily account for the far south populations around the Paraguay and Guaporé Rivers. The western extent of its range is not known exactly, but its abundance there may be limited. It may be extensive in easternmost Bolivia, owing to the presence of the Pantanal region.

These ants are native to Argentina, and the red imported fire ant most likely came from here when they first invaded the United States; in particular, populations of these ants have been found in the provinces of Chaco, Corrientes, Formosa, Santiago del Estero, Santa Fe, and Tucumán. The northeastern regions of Argentina are the most credible guess where the invading ants originate. In Brazil, they are found in northern Mato Grosso and in Rondônia and in São Paulo state. The red imported fire ant and S. saevissima are parapatric in Brazil, with contact zones known in Mato Grosso do Sul, Paraná state and São Paulo. In Paraguay they are found throughout the country, and have been recorded in Boquerón, Caaguazú, Canindeyú, Central, Guairá, Ñeembucú, Paraguarí, and Presidente Hayes departments; Trager claims that the ant is distributed in all regions of the country. They are also found in a large portion of northeastern Bolivia and, to a lesser extent, in northwestern Uruguay.

The red imported fire ant is able to dominate altered areas and live in a variety of habitats. It can survive the extreme weather of the South American rain forest, and in disturbed areas, nests are seen frequently alongside roads and buildings. The ant has been observed frequently around the floodplains of the Paraguay River. In areas where water is present, they are commonly found around: irrigation channels, lakes, ponds, reservoirs, rivers, streams, riverbanks, and mangrove swamps. Nests are found in agricultural areas, coastlands, wetlands, coastal dune remnants, deserts, forests, grasslands, natural forests, oak woodland, mesic forest, leaf-litter, beach margins, shrublands, alongside rail and roads, and in urban areas. In particular, they are found in cultivated land, managed forests and plantations, disturbed areas, intensive livestock production systems, and greenhouses. Red imported fire ants have been found to invade buildings, including medical facilities. In urban areas, colonies dwell in open areas, especially if the area is sunny. This includes: urban gardens, picnic areas, lawns, playgrounds, schoolyards, parks, and golf courses. In some areas, there are on average 200 mounds per acre. During winter, colonies move under pavements or into buildings, and newly mated queens move into pastures. Red imported fire ants are mostly found at altitudes between 5 and 145 m (16 and 476 ft) above sea level.

Mounds range from small to large, measuring 10 to 60 cm (3.9 to 23.6 in) in height and 46 cm (18 in) in diameter with no visible entrances. Workers are only able to access their nests through a series of tunnels that protrude from the central region. Such protrusions can span up to 25 feet away from the central mound, either straight down in to the ground or, more commonly, sideways from the original mound. Constructed from soil, mounds are oriented so that the long portions of the mound face toward the sun during the early morning and before sunset. Mounds are usually oval-shaped with the long axis of the nest orientating itself in a north–south direction. These ants also spend large amounts of energy in nest construction and transporting brood, which is related with thermoregulation. The brood is transported to areas where temperatures are high; workers track temperature patterns of the mound and do not rely on behavioural habits. Inside nests, mounds contain a series of narrow horizontal tunnels, with subterranean shafts and nodes reaching grass roots 10 to 20 cm (3.9 to 7.9 in) below the surface; these shafts and nodes connect the mound tunnels to the subterranean chambers. These chambers are about 5 cm (0.77 inch) and reach depths of 10 to 80 cm (3.9 to 31.5 in). The mean number of ants in a single subterranean chamber is around 200.

Introductions

See also: Red imported fire ants in the United States and Red imported fire ants in AustraliaRed imported fire ants are among the worst invasive species in the world. Some scientists consider the red imported fire ant to be a "disturbance specialist"; human disturbance to the environment may be a major factor behind the ants' impact (fire ants tend to favour disturbed areas). This is shown through one experiment, demonstrating that mowing and plowing in studied areas diminished the diversity and abundance of native ant species, whereas red imported fire ants found on undisturbed forest plots had only diminished a couple of species.

In the United States, the red imported fire ant first arrived in the seaport of Mobile, Alabama, by cargo ship between 1933 and 1945. Arriving with an estimated 9 to 20 unrelated queens, the red imported fire ant was only rare at the time, as entomologists were unable to collect any specimens (with the earliest observations first made in 1942, preceded by a population expansion in 1937); the population of these ants exploded by the 1950s. Since its introduction to the United States, the red imported fire ant has spread throughout the southern states and northeastern Mexico, negatively affecting wildlife and causing economic damage. The expansion of red imported fire ants may be limited since they are almost wiped out during Tennessee winters, thus they may be reaching their northernmost range. However, global warming may allow the red imported fire ant to expand its geographical range. As of 2004, the ant is found in 13 states and occupies over 128 million hectares of land, and as many as 400 mounds can be found on a single acre of land. The United States Department of Agriculture estimates that they expand 120 miles (193 km) westward per year. Likely due to absence of South American competitors— and lower numbers of native competitors— S. invicta dominates more extrafloral nectaries and hemipteran honeydew sources in the Southern U.S. than in its home range.

Red imported fire ants were first discovered in Queensland, Australia, in 2001. The ants were believed to be present in shipping containers arriving at the Port of Brisbane, most likely from North America. Anecdotal evidence suggests fire ants may have been present in Australia for six to eight years prior to formal identification. The potential damage from the red imported fire ant prompted the Australian government to respond rapidly. A joint state and federal funding of A$175 million was granted for a six-year eradication programme. Following years of eradication, eradication rates of greater than 99% from previously infested properties were reported. The program received extended Commonwealth funding of around A$10 million for at least another two years to treat the residual infestations found most recently. In December 2014, a nest was identified at Port Botany, Sydney, in New South Wales. The port was quarantined, and a removal operation took place. In September 2015, populations originating from the United States were found at a Brisbane airport. Hundreds of millions of dollars have since been allocated to their eradication. In August 2023, the Invasive Species Council said that without additional funding, fire ants would probably spread into northern New South Wales and west, potentially into the Murray Darling Basin.

Red imported fire ants have spread beyond North America. The Invasive Species Specialist Group (ISSG) reports the ant inhabiting at least three of the Cayman Islands. However, the sources the ISSG cited give no report about them on the island, but recent collections indicate that they are present. In 2001, red imported fire ants were discovered in New Zealand, but they were successfully eradicated several years later. Red imported fire ants have been reported in India, Malaysia, the Philippines and Singapore. However, these reports were found to be incorrect as the ants collected there were incorrectly identified as the red imported fire ant. In Singapore, the ants were most likely misidentified as well. In India, surveyed ants in Sattur Taluk, India listed the red imported fire ant there in high populations; meanwhile, no reports of the ant were made outside the surveyed area. In 2016, scientists state that despite no presence of the ant in India, the red imported fire ant will more than likely find suitable habitats within India's ecosystem if given the opportunity. The reports in the Philippines most likely misidentified collected material as the red imported fire ant, as no populations have been found there. It was, however, positively identified in Hong Kong and mainland China in 2004, where they have spread into several provinces as well as Macau and Taiwan. No geographic or climatic barriers prevent these ants from spreading further, thus it may spread throughout the tropical and subtropical regions of Asia. In Europe, a single nest was found in the Netherlands in 2002. For the first time, in 2023, ant colonies have been found in Europe.

Around 1980, red imported fire ants began spreading throughout the West Indies, where they were first reported in Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands. Between 1991 and 2001, the ant was recorded from Trinidad and Tobago, several areas in the Bahamas, the British Virgin Islands, Antigua, and the Turks and Caicos Islands. Since then, red imported fire ants have been recorded on more islands and regions, with new populations discovered in: Anguilla, Saint Martin, Barbuda, Montserrat, Saint Kitts, Nevis, Aruba, and Jamaica. The ants recorded from Aruba and Jamaica have only been found on golf courses; these courses import sod from Florida, so such importation may be an important way for the ant to spread throughout the West Indies.

Populations found outside North America originate from the United States. In 2011, the DNA of specimens from Australia, China, and Taiwan was analysed with results showing that they are related to those in the United States. Despite the spread of the red imported fire ant (S. invicta), S. geminata has a greater geographical range, but it can be easily displaced by S. invicta. Because of this, almost all of S. geminata's exotic range in North America has been lost and it has almost disappeared there. On roadsides in Florida, 83% of these sites had S. geminata present when the red imported fire ant was absent, but only 7% when it is present. This means that the ant can probably invade many tropical and subtropical regions where S. geminata populations are present.

Behaviour and ecology

Red imported fire ants are extremely resilient and have adapted to contend with both flooding and drought conditions. If the ants sense increased water levels in their nests, they link together and form a ball or raft that floats, with the workers on the outside and the queen inside. The brood is transported to the highest surface. They are also used as the founding structure of the raft, except for the eggs and smaller larvae. Before submerging, the ants will tip themselves into the water and sever connections with the dry land. In some cases, workers may deliberately remove all males from the raft, resulting in the males drowning. The longevity of a raft can be as long as 12 days. Ants that are trapped underwater escape by lifting themselves to the surface using bubbles which are collected from submerged substrate. Owing to their greater vulnerability to predators, red imported fire ants are significantly more aggressive when rafting. Workers tend to deliver higher doses of venom, which reduces the threat of other animals attacking. Due to this, and because a higher workforce of ants is available, rafts are potentially dangerous to those that encounter them.

Necrophoric behaviour occurs in the red imported fire ant. Workers discard uneaten food and other such wastes away from the nest. The active component was not identified, but the fatty acids accumulating as a result of decomposition were implicated and bits of paper coated with synthetic oleic acid typically elicited a necrophoric response. The process behind this behaviour in imported red fire ants was confirmed by Blum (1970): unsaturated fats, such as oleic acid, elicit corpse-removal behaviour. Workers also show differentiated responses towards dead workers and pupae. Dead workers are usually taken away from the nest, whereas the pupae may take a day for a necrophoric response to occur. Pupae infected by Metarhizium anisopliae are usually discarded by workers at a higher rate: while 47.5% of unaffected corpses are discarded within a day, for affected corpses this figure is 73.8%.

Red imported fire ants have negative impacts on seed germination. The extent of the damage, however, depends on how long seeds are vulnerable for (dry and germinating) and by the abundance of the ants. One study showed that while these ants are attracted to and remove seeds which have adapted for ant dispersal, red imported fire ants damage these seeds or move them in unfavourable locations for germination. In seeds given to colonies, 80% of Sanguinaria canadensis seeds were scarified and 86% of Viola rotundifolia seeds were destroyed. Small percentages of longleaf pine (Pinus palustris) seeds deposited by workers successfully germinate, thus providing evidence that red imported fire ants help the movement of seeds in the longleaf pine ecosystem. Elaiosome-bearing seeds are collected at a higher rate in contrast to nonelaiosome-bearing seeds and do not store them in their nests, but rather in surface trash piles in the mound vicinity.

Foraging and communication

Colonies of the red imported fire ant have tunneling surfaces that protrude out of the surfaces where workers forage. These areas of protrusion tend to be within their own territory, but greater ant colonisation can affect this. Tunnels are designed to allow effective body, limb and antennae interactions with walls, and a worker can also move exceptionally fast inside them (more than nine bodylengths per second). The holes exit out of any point within the colony's territory, and foraging workers may need to travel half a metre to reach the surface. Assuming the average forager travels 5 m, over 90% of foraging time is inside the tunnels during the day and rarely at night. Workers forage in soil temperatures reaching 27 °C (81 °F) and surface temperatures of 12–51 °C (54–124 °F). Workers exposed to temperatures of 42 °C (108 °F) are at risk of dying from the heat. The rate of workers foraging drops rapidly by autumn, and they rarely emerge during winter. This may be due to the effects of soil temperature, and a decreased preference for food sources. These preferences only decrease when brood production is low. In the northern regions of the United States, areas are too cold for the ant to forage, but in other areas such as Florida and Texas, foraging may occur all year round. When it is raining, workers do not forage outside, as exit holes are temporarily blocked, pheromone trails are washed away, and foragers may be physically struck by the rain. The soil's moisture may also affect the foraging behaviour of workers.

When workers are foraging, it is characterised by three steps: searching, recruitment, and transportation. Workers tend to search for honey more often than other food sources, and the weight of food has no impact on searching time. Workers may recruit other nestmates if the food they have found is too heavy, taking as much as 30 minutes for the maximum number of recruited workers to arrive. Lighter food sources take less time and are usually transported rapidly. Foraging workers become scouts and search solely for food outside the surface, and may subsequently die two weeks later from old age.

Workers communicate by a series of semiochemicals and pheromones. These communication methods are used in a variety of activities, such as nestmate recruitment, foraging, attraction, and defence; for example, a worker may secrete trail pheromones if a food source it discovered is too large to carry. These pheromones are synthesized by the Dufour's gland and may trail from the discovered food source back to the nest. The components in these trail pheromones are also species-specific to this ant only, in contrast to other ants with common tail pheromones. The poison sack in this species has been identified as being the novel storage site of the queen pheromone; this pheromone is known to elicit orientation in worker individuals, resulting in the deposition of brood. It is also an attractant, where workers aggregate toward areas where the pheromone has been released. A brood pheromone is possibly present, as workers are able to segregate brood by their age and caste, which is followed by licking, grooming and antennation. If a colony is under attack, workers will release alarm pheromones. However, these pheromones are poorly developed in workers. Workers can detect pyrazines which are produced by the alates; these pyrazines may be involved in nuptial flight, as well as an alarm response.

Red imported fire ants can distinguish nestmates and non-nestmates through chemical communication and specific colony odours. Workers prefer to dig into nest materials from their own colony and not from soil in unnested areas or from other red imported fire ant colonies. One study suggests that as a colony's diet is similar, the only difference between nested and unnested soil was the nesting of the ants themselves. Therefore, workers may transfer colony odour within the soil. Colony odour can be affected by the environment, as workers in lab-reared colonies are less aggressive than those in the wild. Queen-derived cues are able to regulate nestmate recognition in workers and amine levels. However, these cues do not play a major role in colony-level recognition, but they can serve as a form of caste-recognition within nests. Workers living in monogyne societies tend to be extremely aggressive and attack intruders from neighbouring nests. In queenless colonies, the addition of alien queens or workers does not increase aggression among the population.

Diet

Red imported fire ants are omnivores, and foragers are considered to be scavengers rather than predators. The ants' diet consists of dead mammals, arthropods, insects, earthworms, vertebrates, and solid food matter such as seeds. However, this species prefers liquid over solid food. The liquid food the ants collect is sweet substances from plants or honeydew-producing hemipterans. Arthropod prey may include dipteran adults, larvae and pupae, and termites. The consumption of sugar amino acid is known to affect recruitment of workers to plant nectars. Mimic plants with sugar rarely have workers to feed on them, whereas those with sugar and amino acids have considerable numbers. The habitats where they live may determine the food they collect the most; for example, forage success rates for solid foods are highest in lakeshore sites, while high levels of liquid sources were collected from pasture sites. Specific diets can also alter the growth of a colony, with laboratory colonies showing high growth if fed honey-water. Colonies that feed on insects and sugar-water can grow exceptionally large in a short period of time, whereas those that do not feed on sugar-water grow substantially slower. Colonies that do not feed on insects cease brood production entirely. Altogether, the volume of food digested by nestmates is regulated within colonies. Larvae are able to display independent appetites for sources such as solid proteins, amino acid solutions, and sucrose solutions, and they also prefer these sources over dilute solutions. Such behaviour is due to their capability to communicate hunger to workers. The rate of consumption depends on the type, concentration, and state of the food on which they feed. Workers tend to recruit more nestmates to food sources filled with high levels of sucrose than to protein.

Food distribution plays an important role in a colony. This behaviour varies in colonies, with small workers receiving more food than larger workers if a small colony is seriously deprived of food. In larger colonies, however, the larger workers receive more food. Workers can donate sugar water efficiently to other nestmates, with some acting as donors. These "donors" distribute their food sources to recipients, which may also act as donors. Workers may also share a greater portion of their food with other nestmates. In colonies that are not going through starvation, food is still distributed among the workers and larvae. One study shows that honey and soybean oil were fed to the larvae after 12 to 24 hours of being retained by the workers. The ratio distribution of these food sources was 40% towards the larvae and 60% towards the worker for honey, and for soybean oil this figure was around 30 and 70%, respectively. Red imported fire ants also stockpile specific food sources such as insect pieces rather than consuming them immediately. These pieces are usually transported below the mound surface and in the driest and warmest locations.

This species engages in trophallaxis with the larvae. Regardless of the attributes and conditions of each larva, they are fed roughly the same amount of liquid food. The rate of trophallaxis may increase with larval food deprivation, but such increase depends on the size of each larva. Larvae that are fed regularly tend to be given small amounts. To reach satiation, all larvae regardless of their size generally require the equivalent of eight hours of feeding.

Predators

A number of insects, arachnids, and birds prey on these ants, especially when queens are trying to establish a new colony. While in the absence of defending workers, the fire ant queens must rely on their venom to keep off competitor species. Many species of dragonfly, including Anax junius, Pachydiplax longipennis, Somatochlora provocans, and Tramea carolina, capture the queens while they are in flight; 16 species of spiders, including the wolf spider Lycosa timuga and the southern black widow spider (Latrodectus mactans), actively kill red imported fire ants. L. mactans captures all castes of the species (the workers, queens, and males) within its web. These ants constitute 75% of prey captured by the spider. Juvenile L. mactans spiders have also been seen capturing the ants. Other invertebrates that prey on red imported fire ants are earwigs (Labidura riparia) and tiger beetles (Cicindela punctulata). Birds that eat these ants include the chimney swift (Chaetura pelagica), the eastern kingbird (Tyrannus tyrannus), and the eastern bobwhite (Colinus virginianus virginianus). The eastern bobwhite attacks these ants by digging out the mounds looking for young queens. Red imported fire ants have been found in stomach contents inside of armadillos.

Many species of ants have been observed attacking queens and killing them. Apparently, the venom of fire ant queens is chemically adapted to rapidly subdue offending competitor ants. Predatory ants include: Ectatomma edentatum, Ephebomyrmex spp., Lasius neoniger, Pheidole spp., Pogonomyrmex badius, and Conomyrma insana, which is among the most significant. C. insana ants are known to be effective predators against founding queens in studied areas of Northern Florida. The pressure of attacks initiated by C. insana increase over time, causing queens to exhibit different reactions, including escaping, concealment, or defence. Most queens that are attacked by these ants are ultimately killed. Queens that are in groups have higher chances of survival than solitary queens if they are attacked by S. geminata. Ants can attack queens on the ground and invade nests by stinging and dismembering them. Other ants such as P. porcula try to take the head and gaster, and C. clara invade in groups. Also, certain ants try to drag queens out of their nests by pulling on the antennae or legs. Small, monomorphic ants rely on recruitment to kill queens and do not attack them until reinforcements arrive. Aside from killing the queen, some ants may steal the eggs for consumption or emit a repellent that is effective against red imported fire ants. Certain ant species may raid colonies and destroy them.

Parasites, pathogens and viruses

Flies in the genus Pseudacteon (phorid flies) are known to be parasitic to ants. Some species within this genus, such as Pseudacteon tricuspis, have been introduced into the environment for the purpose of controlling the imported fire ant. These flies are parasitoids of the red imported fire ant in its native range in South America, and can be attracted through the ants' venom alkaloids. One species, Pseudacteon obtusus, attacks the ant by landing on the posterior portion of the head and laying an egg. The location of the egg makes it impossible for the ant to successfully remove it. The larvae migrate to the head, then develop by feeding on the hemolymph, muscle tissue, and nervous tissue. After about two weeks, they cause the ant's head to fall off by releasing an enzyme that dissolves the membrane attaching the head to its body. The fly pupates in the detached head capsule, emerging two weeks later. P. tricuspis is another phorid fly that is a parasitoid to this species. Although parasitism pressures by these flies do not affect the ants' population density and activity, it has a small effect on a colony population. The strepsipteran insect Caenocholax fenyesi is known to infect male ants of this species and attack the eggs, and the mite Pyemotes tritici has been considered a potential biological agent against red imported fire ants, capable of parasitising every caste within the colony. Bacteria, such as Wolbachia, has been found in the red imported fire ant; three different variants of the bacteria are known to infect the red imported fire ant. However, its effect on the ant is unknown. Solenopsis daguerrei is a reproductive parasite to red imported fire ant colonies.

A large variety of pathogens and nematodes also infect red imported fire ants. Pathogens include Myrmecomyces annellisae, Mattesia spp., Steinernema spp., a mermithid nematode, Vairimorpha invictae, which can be transmitted via live larvae and pupae and dead adults and Tetradonema solenopsis, which can be fatal to a large portion of a colony. Individuals infected by Metarhizium anisopliae tend to perform trophallaxis more frequently and have an enhanced preference to quinine, an alkaloid substance. Phorid flies with Kneallhazia solenopsae can serve as vectors in transmitting the disease to the ants. Weakening the colony, infections from this disease are localised within the body fat, with spores only occurring in adult individuals. The mortality of an infected colony tends to be greater in contrast to those that are healthy. These ants are a host to Conidiobolus, Myrmicinosporidium durum, and Beauveria bassiana, each of which are parasitic fungi. Infected individuals have spores all over their bodies and appear darker than usual. The toxicity from antimicrobial property of volatiles produced by the ants can significantly reduce the germination rate of B. bassiana within the colony.

A virus, S. invicta 1 (SINV-1), has been found in about 20% of fire ant fields, where it appears to cause the slow death of infected colonies. It has proven to be self-sustaining and transmissible. Once introduced, it can eliminate a colony within three months. Researchers believe the virus has potential as a viable biopesticide to control fire ants. Two more viruses have also been discovered: S. invicta 2 (SINV-2) and S. invicta 3 (SINV-3). Polygynous colonies tend to face greater infections in contrast to monogynous colonies. Multiple virus infections can also occur.

Lifecycle and reproduction

Nuptial flight in red imported fire ants begins during the warmer seasons of the year (spring and summer), usually two days after rain. The time alates emerge and mate is between noon and 3:00 pm. Nuptial flights recorded in North Florida have, on average, 690 female and male alates participating in a single flight. Males are the first to leave the nest, and both sexes readily undertake flight with little to no preflight activity. However, workers swarm the mound excitedly stimulated by mandibular glands within the head of the alates. As mounds do not have holes, workers form holes during nuptial flight as a way for the alates to emerge. This behaviour in workers, elicited by the pheromones, includes rapid running and back-and-forth movements, and increased aggression. Workers also cluster themselves around the alates as they climb up on vegetation, and in some cases, attempt to pull them back down before they take flight. Chemical cues from males and females during nuptial flight attract workers, but chemical cues released by workers do not attract other nestmates. It also induces alarm-recruitment behaviour in workers which results in a higher rate of alate retrieval.

Males fly at higher elevations than females: captured males are usually 100 to 300 m (330 to 980 ft) above the surface, whereas the females are only 60 to 120 m (200 to 390 ft) above the surface. A nuptial flight takes place for roughly half an hour and females generally fly for less than 1.6 km (0.99 mi) before landing. About 95% of queens successfully mate and only mate once; some males may be infertile due to the testicular lobes failing to develop. In polygyne colonies, males do not play a significant role and most are, therefore, sterile; one of the reasons for this is to avoid mating with other ant species. This also makes male mortality selective, which may affect the breeding system, mating success and, gene flow. Ideal conditions for a nuptial flight to begin is when humidity levels are above 80% and when the soil temperature is above 18 °C (64 °F). Nuptial flights only occur when the ambient temperature is 24–32 °C (75–90 °F).

Queens are often found 1–2.3 miles from the nest they flew from. Colony founding can be done by an individual or in groups, known as pleometrosis. This joint effort of the co-foundresses contributes to the growth and survival of the incipient colony; nests founded by multiple queens begin the growth period with three times as many workers when compared to colonies founded by a single queen. Despite this, such associations are not always stable. The emergence of the first workers instigates queen-queen and queen-worker fighting. In pleometrotic conditions, only one queen emerges victorious, whereas the queens that lost are subsequently killed by the workers. The two factors that could affect the survival of individual queens are their relative fighting capabilities and their relative contribution to worker production. Size, an indicator of fighting capacity, positively correlates with survival rates. However, manipulation of the queen's relative contribution to worker production had no correlation with survival rate.

A single queen lays around 10 to 15 eggs 24 hours after mating. In established nests, a queen applies venom onto each egg that perhaps contains a signal calling for workers to move it. These eggs remain unchanged in size for one week until they hatch into larvae. By this time, the queen will have laid about 75 to 125 more eggs. The larvae that hatch from their eggs are usually covered in their shell membranes for several days. The larvae can free their mouthparts from their shells using body movements, but still need assistance from workers with hatching. The larval stage is divided into four instars, as observed through the moulting stages. At the end of each moult, a piece of unknown material is seen connected to the exuviae if they are isolated from the workers. The larval stage lasts between six and 12 days before their bodies expand significantly and become pupae; the pupal stage lasts between nine and 16 days.

As soon as the first individuals reach the pupal stage, the queen ceases egg production until the first workers mature. This process takes two weeks to one month. The young larvae are fed oils which are regurgitated from her crop, as well as trophic eggs or secretions. She also feeds the young her wing muscles, providing the young with needed nutrients. The first generation of workers are always small because of the limit of nutrients needed for development. These workers are known as minims or nanitics, which burrow out of the queen's chamber and commence foraging for food needed for the colony. Mound construction also occurs at this time. Within a month after the first generation is born, larger workers (major workers) start to develop, and within six months, the mound will be noticeable, if viewed, and houses several thousand residents. A mature queen is capable of laying 1,500 eggs per day; all workers are sterile, so cannot reproduce.

A colony can grow exceptionally fast. Colonies that housed 15–20 workers in May grew to over 7,000 by September. These colonies started to produce reproductive ants when they were a year old, and by the time they were two years old, they had over 25,000 workers. The population doubled to 50,000 when these colonies were three years old. At maturity, a colony can house 100,000 to 250,000 individuals, but other reports suggest that colonies can hold more than 400,000. Polygyne colonies have the potential to grow much larger than monogyne colonies.

Several factors contribute to colony growth. Temperature plays a major role in colony growth and development; colony growth ceases below 24 °C and developmental time decreases from 55 days at temperatures of 24 °C to 23 days at 35 °C. Growth in established colonies only occurs at temperatures between 24 and 36 °C. Nanitic brood also develops far quicker than minor worker brood (around 35% faster), which is beneficial for founding colonies. Colonies that have access to an unlimited amount of insect prey are known to grow substantially, but this growth is further accelerated if they are able to access plant resources colonised by hemipteran insects. In incipient monogyne colonies where diploid males are produced, colony mortality rates are significantly high and colony growth is slow. In some cases, monogyne colonies experience 100% mortality rates in the early stages of development.

The life expectancy of a worker ant depends on its size, although the overall average is around 62 days. Minor workers are expected to live for about 30 to 60 days, whereas the larger workers live much longer. Larger workers, which have a life expectancy of 60 to 180 days, live 50–140% longer than their smaller counterparts, but this depends on the temperature. However, workers kept in laboratory conditions have been known to live for 10 to 70 weeks (70 days to 490 days); the maximum recorded longevity of a worker is 97 weeks (or 679 days). The queens live much longer than the workers, with a lifespan ranging from two years to nearly seven years.

In colonies, queens are the only ants able to alter sex ratios which can be predicted. For example, queens originating from male-producing colonies tend to produce predominantly males, while queens that came from female-favoured sex ratio colonies tend to produce females. Queens also exert control over the production of sexuals through pheromones that influence the behaviours of workers toward both male and female larvae.

Monogyny and polygyny

There are two forms of society in the red imported fire ant: polygynous colonies and monogynous colonies. Polygynous colonies differ substantially from monogynous colonies in social insects. The former experience reductions in queen fecundity, dispersal, longevity, and nestmate relatedness. Polygynous queens are also less physogastric than monogynous queens and workers are smaller. Understanding the mechanisms behind queen recruitment is integral to understanding how these differences in fitness are formed. It is unusual that the number of older queens in a colony does not influence new queen recruitment. Levels of queen pheromone, which appears to be related to queen number, play important roles in the regulation of reproduction. It would follow that workers would reject new queens when exposed to large quantities of this queen pheromone. Moreover, evidence supports the claim that queens in both populations enter nests at random, without any regard for the number of older queens present. There is no correlation between the number of older queens and the number of newly recruited queens. Three hypotheses have been posited to explain the acceptance of multiple queens into established colonies: mutualism, kin selection, and parasitism. The mutualism hypothesis states that cooperation leads to an increase in the personal fitness of older queens. However, this hypothesis is not consistent with the fact that increasing queen number decreases both queen production and queen longevity. Kin selection also seems unlikely given that queens have been observed to cooperate under circumstances where they are statistically unrelated. Therefore, queens experience no gain in personal fitness by allowing new queens into the colony. Parasitism of preexisting nests appears to be the best explanation of polygyny. One theory is that so many queens attempt to enter the colony that the workers get confused and inadvertently allow several queens to join it.

Monogyne workers kill foreign queens and aggressively defend their territory. However, not all behaviours are universal, primarily because worker behaviours depend on the ecological context in which they develop, and the manipulation of worker genotypes can elicit change in behaviours. Therefore, behaviours of native populations can differ from those of introduced populations. In a study to assess the aggressive behaviour of monogyne and polygyne red fire ant workers by studying interaction in neutral arenas, and to develop a reliable ethogram for readily distinguishing between monogyne and polygyne colonies of red imported fire ants in the field, monogyne and polygyne workers discriminated between nestmates and foreigners as indicated by different behaviours ranging from tolerance to aggression. Monogyne ants always attacked foreign ants independently if they were from monogyne or polygyne colonies, whereas polygyne ants recognised, but did not attack, foreign polygyne ants, mainly by exhibiting postures similar to behaviours assumed after attacks by Pseudacteon phorids. Hostile versus warning behaviours were strongly dependent on the social structure of workers. Therefore, the behaviour toward foreign workers was a method of characterising monogyne and polygyne colonies. Most colonies in the southeastern and south-central US tend to be monogynous.

The monogynous red imported fire ant colony territorial area and the mound size are positively correlated, which, in turn, is regulated by the colony size (number and biomass of workers), distance from neighbouring colonies, prey density, and by the colony's collective competitive ability. In contrast, nestmate discrimination among polygynous colonies is more relaxed as workers tolerate conspecific ants alien to the colony, accept other heterozygote queens, and do not aggressively protect their territory from polygyne conspecifics. These colonies might increase their reproductive output as a result of having many queens and the possibility of exploiting greater territories by means of cooperative recruitment and interconnected mounds.

A social chromosome is present in the red imported fire ant. This chromosome can differentiate the social organisation of a colony carrying one of two variants of a supergene (B and b) which contains more than 600 genes. The social chromosome has often been compared to sexual chromosomes because they share similar genetic features and they define colony phenotype in a similar way. For example, colonies exclusively carrying the B variant of this chromosome accept single BB queens, but colonies with both B and b variants will accept multiple Bb queens only. Differences in another single gene can also determine whether the colony will have single or multiple queens.

Relationship with other animals

Competition

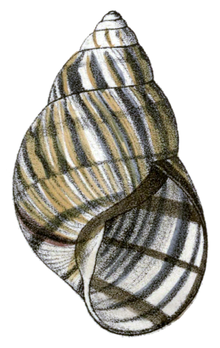

When polygyne forms invade areas where colonies have not yet been established, the diversity of native arthropods and vertebrates declines greatly. This is evident as populations of isopods, mites and tumblebug scarabs decline significantly. They can also significantly alter the populations of many fly and beetle families, including: Calliphoridae, Histeridae, Muscidae, Sarcophagidae, Silphidae, and Staphylinidae. Despite this, one review found that certain insects may be unaffected by red imported fire ants; for example, the density of isopods decreases in red imported fire ant infested areas, but crickets of the genus Gryllus are unaffected. There are some cases where the diversity of certain insect and arthropod species increase in areas where red imported fire ants are present. Red imported fire ants are important predators on cave invertebrates, some of which are endangered species. This includes harvestmen, pseudoscorpions, spiders, ground beetles, and pselaphid beetles. The biggest concern is not the ant itself, but the bait used to treat them because this can prove fatal. Stock Island tree snails (Orthalicus reses) are extinct in the wild; predation by red imported fire ants is believed to be the major factor in the snail's extinction. Overall, red imported fire ants prefer specific arthropods to others, although they attack and kill any invertebrate that cannot defend itself or escape. Arthropod biodiversity increases once red imported fire ant populations are either reduced or eradicated.

Interactions between red imported fire ants and mammals have been rarely documented. However, deaths of live-trapped animals by red imported fire ants have been observed. Mortality rates in eastern cottontail (Sylvilagus floridanus) young range from 33 to 75% because of red imported fire ants. It is believed that red imported fire ants have a strong impact on many herpetofauna species; scientists have noted population declines in the Florida kingsnake (Lampropeltis getula floridana), and eggs and adults of the eastern fence lizard (Sceloporus undulatus) and six-lined racerunner (Aspidoscelis sexlineata) are a source of food. Because of this, eastern fence lizards have adapted to have longer legs and new behaviours to escape the red imported fire ant. Additionally, another lizard species, Sphaerodactylus macrolepis are also a target of the fire ants' and have developed tactics to fend them off, such as tail flicks. Adult three-toed box turtles (Terrapene carolina triunguis), Houston toad (Anaxyrus houstonensis) juveniles, and American alligator (Alligator mississippiensis) hatchlings are also attacked and killed by these ants. Despite this mostly-negative association, one study shows that red imported fire ants may be capable of impacting vector-borne disease transmissions by regulating tick populations and altering vector and host dynamics, thereby reducing transmission rates not only to animals, but to humans as well.

Mortality rates have been well observed in birds; there have been instances where no young have survived to adulthood in areas with high fire ant density. Many birds including cliff nesting swallows, ducks, egrets, quail, and terns have been affected by red imported fire ants. Ground nesting birds, particularly the least tern (Sterna antillarum), are vulnerable to fire ant attacks. The impact of red imported fire ants on colonial breeding birds is especially severe; waterbirds can experience a mortality rate of 100%, although this factor was lower for early-nesting birds. Brood survival decreases in American cliff swallows (Petrochelidon pyrrhonota) if they are exposed to foraging workers. Songbird nest survival decreases in areas with red imported fire ants present, but survival rates in white-eyed vireo (Vireo griseus) and black-capped vireo (Vireo atricapilla) nests increase from 10% to 31% and 7% to 13% whenever fire ants are not present or when they are unable to attack them. Red imported fire ants may indirectly contribute to low brood survival in the Attwater's prairie chicken. It was first thought that the ants were linked to the decline of overwintering birds such as the loggerhead shrike (Lanius ludovicianus), but a later study showed that ant eradication efforts using the pesticide Mirex, which was known to have toxic side effects, was largely to blame.

Red imported fire ants are strong competitors with many ant species. They have managed to displace many native ants which has led to a number of ecological consequences. However, studies show that these ants are not always superior competitors that suppress native ants. Habitat disturbance prior to their arrival, and recruitment limitations, are more plausible reasons why native ants are suppressed. Between Tapinoma melanocephalum and Pheidole fervida, the red imported fire ant is stronger than both species but shows different levels of aggression. For example, they are less hostile towards T. melanocephalum in contrast to P. fervida. Mortality rates in T. melanocephalum and P. fervida when fighting with red imported fire ants are high, being 31.8% and 49.9% respectively. The mortality rate for red imported fire ant workers, however, is only 0.2% to 12%. The imported crazy ant (Nylanderia fulva) exhibits greater dominance than the red imported fire ant and has been known to displace them in habitats where they encounter each other in. Larger colonies of pavement ants (Tetramorium caespitum) can destroy red imported fire ant colonies, leading entomologists to conclude that this conflict between the two species may help impede the spread of the red imported fire ant. Individuals infected by SINV-1 can be killed faster than healthy individuals by Monomorium chinense. This means that ants infected with SINV-1 are weaker than their healthy counterparts and more than likely will be eliminated by M. chinense. However, major workers, whether they are infected or not, are rarely killed.